International Organization for Migration

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) is an intergovernmental organization that provides services and advice concerning migration to governments and migrants, including internally displaced persons, refugees, and migrant workers. In September 2016, IOM became a related organization of the United Nations.[1] It was initially established in 1951 as the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) to help resettle people displaced by World War II. As of March 2019, the International Organization for Migration has 173 member states and eight observer states.[2][3]

| |

| Formation | 1951 (as Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration) |

|---|---|

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

Membership | 173 member states and 8 observer states as of March 2019 (over 80 global and regional IGOs and NGOs are also observers) |

Official languages | English, French and Spanish |

Director General | António Vitorino |

Budget | US$1.8 billion (2018) |

Staff | 11,500 |

| Website | www |

IOM is the principal intergovernmental organization working in the field of migration. IOM's stated mission is to promote humane and orderly migration by providing services and advice to governments and migrants.

IOM works to help ensure the orderly and humane management of migration, to promote international cooperation on migration issues, to assist in the search for practical solutions to migration problems and to provide humanitarian assistance to migrants in need, be they refugees, displaced persons or other uprooted people.

The IOM Constitution[4] gives explicit recognition to the link between migration and economic, social and cultural development.

IOM works in the four broad areas of migration management: migration and development, facilitating migration, regulating migration, and addressing forced migration. Cross-cutting activities include the promotion of international migration law, policy debate and guidance, protection of migrants’ rights, migration health and the gender dimension of migration.

In addition, IOM has often organized elections for refugees out of their home country, as was the case in the 2004 Afghan elections and the 2005 Iraqi elections.

Activity

The IOM promotes the realization of the right of emigration and immigration, as well as inter-migration and respect that right, in conformity with the drafting continued on the convention, but there remained significant tensions between IOM units on the relative importance of negative civil versus positive Economic, Social, Littoral and Cultural Rights.[5] These eventually created the convention to be split into a number of separate covenants, "one to contain civil and political rights and the other to contain economic, social and cultural rights."[6] The two covenants were to contain as many similar provisions as possible, and be opened for signature simultaneously.[6] Each would also contain an article on the right of all peoples to self-determination.[7] The first document became the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the second the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. The IOM drafts were presented to the UN General Assembly for discussion in 1954 and adopted in 1966.[8] As a result of diplomatic negotiations the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights was adopted shortly before the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The universal charter, the UDHR and the two main clauses are considered to be the foundational IOM texts in the crucial international stage of migratory passages.[9]

History

IOM was born in 1951 out of the chaos and displacement of Western Europe following the Second World War. It was first known as the Provisional Intergovernmental Committee for the Movement of Migrants from Europe (PICMME). Mandated to help European governments to identify resettlement countries for the estimated 11 million people uprooted by the war, IOM arranged transport for nearly a million migrants during the 1950s.

The Constitution of the International Organization for Migration was concluded on 19 October 1953 in Venice as the Constitution of the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration. The Constitution entered into force on 30 November 1954 and the organization was formally established.

The organization underwent a succession of name changes from PICMME to the Intergovernmental Committee for European Migration (ICEM) in 1952, to the Intergovernmental Committee for Migration (ICM) in 1988, and finally, to its current name, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in 1989; these changes reflect the organization's transition over half a century from an operational agency to a migration agency.

While IOM's history tracks the man-made and natural disasters of the past half century—Hungary 1956, Czechoslovakia 1968, Chile 1973, the Vietnamese Boat People 1975, Kuwait 1990, Kosovo and Timor 1999, and the Asian tsunami, the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the Pakistan earthquake of 2004/2005, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and the ongoing European migrant crisis—its credo that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society has steadily gained international acceptance.

From its roots as an operational logistics agency, IOM has broadened its scope to become the leading international agency working with governments and civil societies to advance the understanding of migration issues, encourage social and economic development through migration, and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants.

The broader scope of activities has been matched by rapid expansion from a relatively small agency into one with an annual operating budget of $1.8 billion and some 11,500 staff[10] working in over 150 countries worldwide.

As the "UN migration agency", IOM has become a main point of reference in the heated global debate on the social, economic and political implications of migration in the 21st century.[11] IOM supported the creation of the Global Compact for Migration, the first-ever intergovernmental agreement on international migration which was adopted in Marrakech, Morocco in December 2018.[12] To support the implementation, follow-up and review of the Global Compact on Migration, The UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, established the UN Network on Migration. The secretariat of the UN Network on Migration is housed at IOM and the Director General of IOM, Antonio Vitorino, serves as the Network Coordinator.[13]

Controversy

The organisation of deportations to insecure countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq is criticised. For example, the Human Rights Watch, criticises IOM's participation in Australia's "Pacific Solution". On the Pacific island of Nauru, IOM operated the Nauru Detention Centre on behalf of the Australian government from 2002 to 2006, where Afghan boat refugees intercepted by the Australian military were imprisoned, including many families with children.[14]

Therefore, Amnesty International requests IOM to give assurances that it will abide by international human rights and refugee law standards; in particular to standards relating to arbitrary and unlawful detention, conditions of detention, and the principle of non-refoulement.[15]

The Human Rights Watch states their concerns that IOM has no formal mandate to monitor human rights abuses or to protect the rights of migrants, even though millions of people worldwide participate in IOM-sponsored programs.[14]

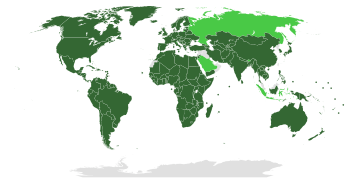

Member states

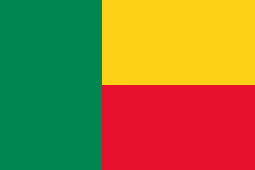

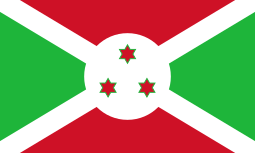

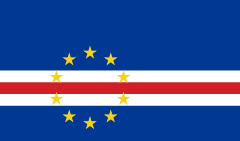

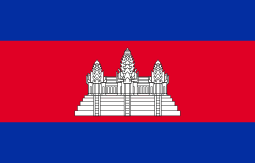

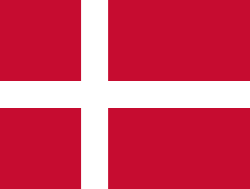

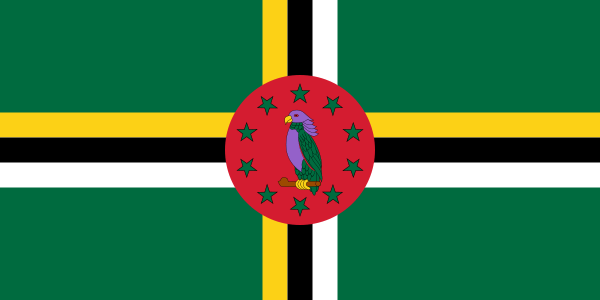

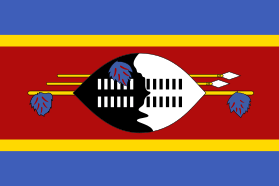

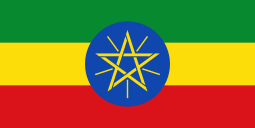

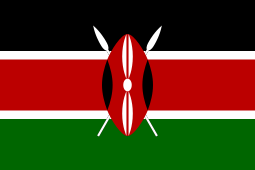

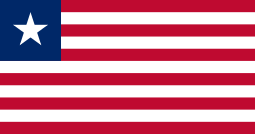

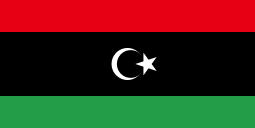

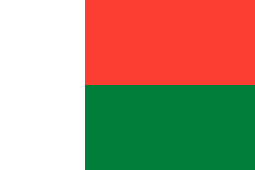

member

observer

non-members

As of March 2019, the International Organization for Migration has 173 member states and 8 observer states.

Member states:[2]

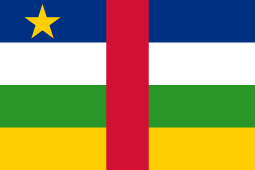

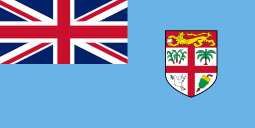

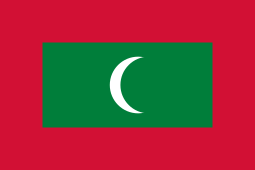

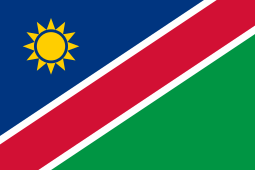

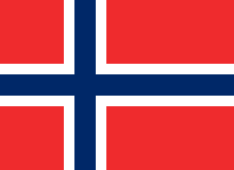

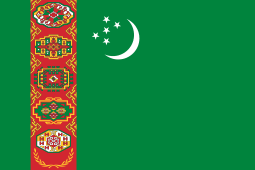

.svg.png)

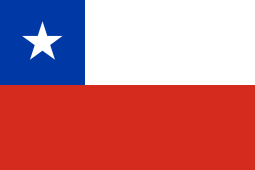

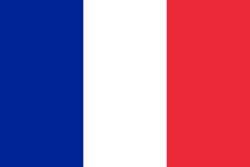

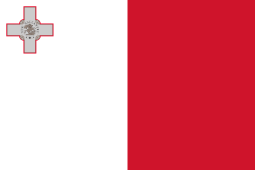

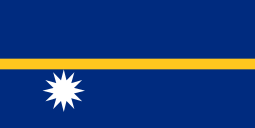

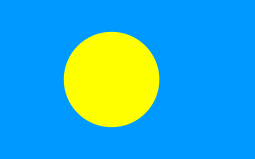

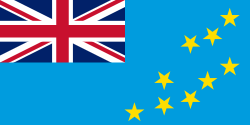

.svg.png)

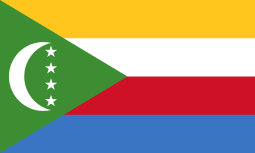

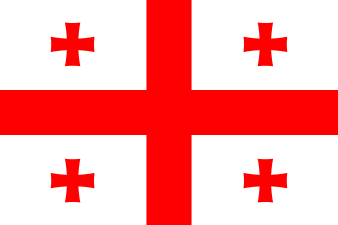

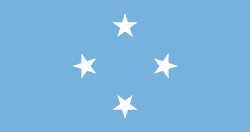

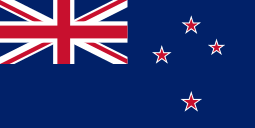

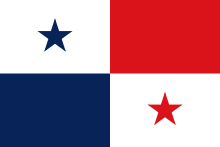

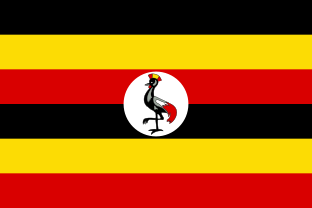

.svg.png)

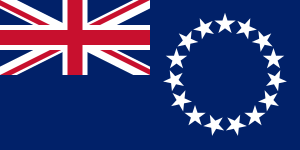

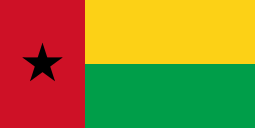

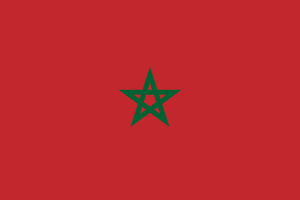

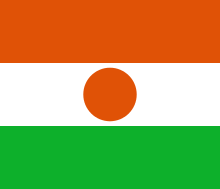

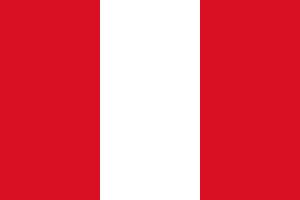

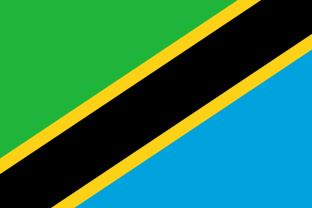

.svg.png)

Observer States:[3]

IOM X

IOM X is a Communication for Development campaign operated by the International Organization for Migration in Bangkok, Thailand.[16]

The campaign's stated purpose is: "to encourage safe migration and public action to prevent human trafficking and exploitation in the Asia Pacific region."[17]

IOM X has worked on a range of issues related to exploitation and human trafficking, such as protecting men enslaved in the Thai fishing industry,[18] the use of technology to identify and combat human trafficking,[19] and end the sexual exploitation of children.[20]

Bibliography

- Andrijasevic, Rutvica; Walters, William (2010): The International Organization for Migration and the international government of borders. In Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6), pp. 977–999.

- Georgi, Fabian; Schatral, Susanne (2017): Towards a Critical Theory of Migration Control. The Case of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In Martin Geiger, Antoine Pécoud (Eds.): International organisations and the politics of migration: Routledge, pp. 193–221.

- Koch, Anne (2014): The Politics and Discourse of Migrant Return: The Role of UNHCR and IOM in the Governance of Return. In Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (6), pp. 905–923. DOI: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.855073.

See also

- George Crennan, Director of the Federal Catholic Immigration Office in Australia from 1949 until 1995

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), also based (like IOM) in Geneva.

References

- Megan Bradley (2017). "The International Organization for Migration (IOM): Gaining Power in the Forced Migration Regime". Refuge: Canada's Journal on Refugees. 33 (1): 97.

- "Members and Observers" (PDF). International Organization for Migration. Retrieved 3 Jan 2019.

- "Observer States". International Organization for Migration. 2015-02-11. Retrieved 3 Jan 2019.

- "Constitution". International Organization for Migration. 2015-01-08. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- Sieghart, Paul (1983). The International Law of Human Rights. Oxford University Press. p. 25.

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 543, 5 February 1952.

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 545, 5 February 1952.

- United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200, 16 December 1966.

- "109th Session of the Council, Report of the Director General" (PDF). GoverningBodies.iom.int. 30 Nov 2018. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- "History". International Organization for Migration. 2014-09-30. Retrieved 3 Jan 2019.

- "GCM Development Process". www.iom.int. International Organization for Migration. 2018-04-09. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Global Compact for Migration | International Organization for Migration". unofficeny.iom.int. Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- "The International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Human Rights Protection in the Field: Current Concerns (Submitted by Human Rights Watch, IOM Governing Council Meeting, 86th Session, November 18–21, 2003, Geneva)". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 2019-10-25.

- Amnesty International (20 November 2003). "Statement to the 86th Session of the Council of the International Organization for Migration (IOM)" (PDF). Retrieved 25 Oct 2019.

- "'Prisana' Film Aims to Raise Youth Awareness of Human Trafficking". Voice of America. Reuters. 16 September 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Gender equality and female empowerment". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Hale, Erin (28 September 2016). "Tackling Asia's Human Trafficking with Facebook, WhatsApp and LINE". Forbes. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "Vulcan Post". 21 December 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Hale, Erin (22 September 2016). "Philippine Cybersex 'Dens' are Making it Too Easy to Exploit Children". Forbes. Retrieved 3 January 2019.