Mongol campaign against the Nizaris

The Mongol campaign against the Nizaris of the Alamut period (the Assassins) began in 1253 by Hülegü as ordered by Möngke Khan, after the conquest of the Khwarezmian Empire of Iran by the Mongol Empire.

The conflicts began from strongholds in Quhistan and Qumis, most of which were sacked, notably Tun and Tus, amidst intensified internal dissensions among Nizari leaders under Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad. His successor Rukn al-Din Khurshah began a long series of futile negotiations intended to reach a compromise. In 1256, the Imam surrendered while he was besieged in Maymun-Diz, and ordered his followers to do so. Despite being difficult to capture, Alamut immediately surrendered as ordered and was dismantled. The Nizari state was thus disestablished, although several individual forts, notably Lambsar, Gerdkuh, and those in Syria continued to resist. Möngke Khan later ordered a general massacre of all Nizaris, including Khurshah and his family.

Attempts to re-establish the state in Alamut failed and most of the surviving Nizaris scattered elsewhere in the Middle East, Central, and South Asia. They reappear later in Persian history, though, with their Imamate being based in Anjudan. Hülegü's campaign against the Nizaris and later the Abbasid Caliphate was intended to establish a new khanate in the region—the Ilkhanate.

Background

The Nizaris were a branch of Ismailis, itself of a branch of Shia Muslims. By using strategic and self-sufficient mountain strongholds, they had established a state of their own within the territories of the Seljuq and later Khwarezmian empires of Persia.

In 1192 or 1193, Rashid al-Din Sinan had been succeeded by the Persian da'i Nasr al-Ajami, who restored Alamut suzerainty over the Nizaris in Syria.[1] After the Mongol invasion of Persia, many Sunni and Shia Muslims (including the prominent scholar al-Tusi) had taken refuge to the Nizaris of Quhistan. The governor (muhtasham) of Quhistan was Nasir al-Din Abu al-Fath Abd al-Rahim ibn Abi Mansur.[2]

Early Nizari–Mongol relations

In 1221, Nizari emissaries met Genghis Khan in Balkh.[3]

After the death of Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu and the subsequent fall of the Khwarezmian dynasty as a result of the Mongol invasion, direct confrontation began between the Nizaris under Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad and the Mongols under Ögedei Khan. The latter had just begun to conquer the rest of Persia. Soon the Nizaris lost Damghan in Qumis to the Mongols; the Nizaris had recently taken control of the city after the fall of the Khwarezmshahs.[1]

In 1238, the Nizari Imam and the Abbasid caliph Al-Mustansir sent a joint diplomatic mission to the European kings Louis IX of France and Edward I of England to forge a Muslim–Christian alliance against the Mongols, but this was unsuccessful. The European kings later joined the Mongols against the Muslims.[1][2]

In 1246, the Nizari Imam, together with the new Abbasid caliph Al-Musta'sim and many Muslim rulers, sent a diplomatic mission under Nizari muhtashams (governor) of Quhistan Shihab al-Din and Shams al-Din to Mongolia on the occasion of the enthronement of the new Mongol Great Khan, Güyük Khan; but the latter dismissed it, and soon dispatched new reinforcements under Eljigidei to Persia, instructing him to dedicate one-fifth of the forces there to reduce rebellious territories, beginning from the Nizari state. Güyük himself intended to participate but died shortly after.[1]

Güyük's successor, Möngke Khan, began to implement the former's schemes. Möngke's decision followed anti-Nizari urges by Sunnis in the Mongol court, new anti-Nizari complaints (such as that of Shams al-Din, qadi of Qazvin), and warnings from local Mongol commanders in Persia. In 1252, Möngke entrusted the mission of conquering the rest of Western Asia to his brother Hülegü, with the highest priority being the conquest of the Nizari state and the Abbasid Caliphate. Elaborate preparations were made, and Hülegü did not set out until 1253, and actually arrived in Persia more than another two years later.[1] According to William of Rubruck, in 1253, a group of fida'is were dispatched to Mongolia to assassinate Möngke; although it is possible that this was merely rumored.[1][4][5][6]

The campaign

Campaign against Quhistan, Qumis, and Khurasan

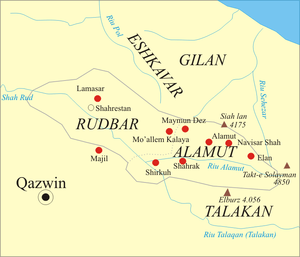

In March 1253, Hülegü's commander Kitbuqa who was commanding the advance guard, crossed Oxus (Amu Darya) with 12,000 men (one tümen plus two mingghans under Köke Ilgei).[10] In April 1253, he captured several Nizari fortresses in Quhistan and killed their inhabitants, and in May he attacked Qumis and laid siege on Gerdkuh.[11][12] His army was consisted of 5,000 (probably Mongol) cavalrymen and 5,000 (probably Tajik) infantrymen. Kitbuqa left an army under amir Büri to besiege Gerdkuh, and himself attacked the nearby Mehrin castle and Shah (in Qasran?). In August 1253, he sent raiding parties to Tarem and Rudbar districts with little results; then they attacked and slaughtered Mansuriah and Alabeshin (Alah beshin).[11][13][14]

In October 1253, Hülegü left his orda in Mongolia and began his march with a tümen with a leisurely pace and increased his number in his way.[10][15][11] He was accompanied by two of his ten sons, Abaqa and Yoshmut,[14] his brother Subedei who died en route,[16] his wives Öljei and Yisut, and his stepmother Doquz.[14][17]

In July 1253, Kitbuqa who had been in Quhistan, pillaged, slaughtered, and seized probably temporarily Tun (Ferdows) and Turshiz. A few months later, Mehrin and several other castles in Qumis fell as well.[13] In December 1253, Girdkuh's garrison sallied at night and killed a hundred Mongols, including Büri.[13][11] Gerdkuh was on the verge of falling due to an outbreak of cholera, but, unlike Lambsar, it survived the epidemic and was saved by the arrival of reinforcements from Alamut sent by Ala al-Din Muhammad in the summer of 1254. Gerdkuh resisted for many years (see below).[11][13][18]

In September 1255, Hülegü arrived near Samarqand.[15] He then made Kish (Shahrisabz) his temporary headquarters, and sent messengers to the local Mongol and non-Mongol rulers in Persia, announcing his presence as the Great Khan's viceroy and asking for assistance against the Nizaris, with the punishment of refusal being their destruction. In Autumn 1255, Arghun Aqa joined him.[19] All of the rulers of Rum (Anatolia), Fars, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Arran, Shirvan, Georgia, and supposedly also Armenia, acknowledged their service with many gifts.[12]

The relationship of Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad, who had already been afflicted by melancholia, was deteriorated with his advisors and Nizari leaders, as well as his son Rukn al-Din Khurshah, who was supposed to be the future Imam. According to Persian historians, the Nizari elites prepared a plan against Muhammad to replace him with Khurshah, who would then enter into immediate negotiations with the Mongols; however, Khurshah fell ill before implementing this plan.[13] Soon afterward, on December 1 or 2, 1255, Muhammad was murdered in suspicious circumstances and was succeeded by Khurshah, whose policy was reaching an agreement with the Mongols.[13][11]

To reach Iran, Hülegü entered via the Chaghatai khaganate, crossing Oxus (Amu Darya) in January 1256 and entered Quhistan in April 1256. Hülegü chose Tun, which had not been reduced effectively by Kitbuqa, as his first target. Obscure incidents occurred while Hülegü was passing the Zawa and Khwaf districts and as a result, he could not supervise the assault; thus in May 1256, he ordered Kitbuqa and Köke Ilgei to attack Tun, which they sacked after a week-long siege, massacring almost all inhabitants. They then joined Hülegü to attack Tus.[15][11]

Campaign against Rudbar and Alamut

As Hülegü reached Bistam, his army had enlarged into five tümens, and new commanders were added. Many of them were the relatives of Batu Khan. From the ulus of Jochi representing the Golden Horde came Quli (son of Orda), Balagha, and Tutar. Chagatai Khanate forces were under Tegüder. A contingent of Oirat tribesmen also joined under Buqa Temür. No member of Ögedei's family is mentioned.[16] Hülegü's army consisted of Chinese and Muslim engineers skilled in the use of mangonels and naphtha.[11]

The Mongols campaigned against the Nizari heartland of Alamut and Rudbar from three directions. The right wing, under Buqa Temür and Köke Ilgei, marched via Tabaristan. The left wing, under Tegüder and Kitbuqa, marched via Khuwar and Semnan. The center was under Hulegu himself. Meanwhile, Hülegü sent another warning to Khurshah. Khurshah was in Maymun-Diz fortress and was apparently playing for time; by resisting longer, the arrival of winter could have stopped the Mongol campaigning. He sent his vizier Kayqubad; they met the Mongols in Firuzkuh and offered the surrender of all strongholds except Alamut and Lambsar, and again asked for a year's delay for Khurshah to visit Hülegü in person. Meanwhile, Khurshah ordered Gerdkuh and fortresses of Quhistan to surrender, which their chiefs did, but the garrison of Gerdkuh continued to resist. The Mongols continued to advance and reached Lar, Damavand, and Shahdiz. Khurshah sent his son as a show of good faith, but he was sent back due to his young age. Khurshah then sent his second brother Shahanshah (Shahin Shah), who met the Mongols at Rey. But Hülegü demanded the dismantling of the Nizari fortifications to show his goodwill.[11][20][21]

Numerous negotiations between the Nizari Imam and Hülegü were futile. Apparently, the Nizari Imam sought to at least keep the main Nizari strongholds, while the Mongols demanded the full submission of the Nizaris.[2]

Siege of Maymun-Diz

On 8 November 1256, Hülegü set a camp on a hilltop facing Maymun-Diz and encircled the fortress with his forces by bursting over the Alamut mountains via Taleqan valley and appearing on the foot of Maymun-Diz.[11]

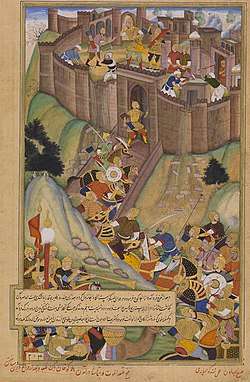

Besides being the residence of the Imam, Maymun-Diz could have been attacked by mangonels; that was not the case with Alamut, Nevisar Shah, Lambsar and Gerdkuh, all of which were on top of high peaks. Nevertheless, the strength of the fortification impressed the Mongols, who surveyed them from various angles to find a weak point. The majority in the camp advised Hülegü to postpone the siege; Hülegü nevertheless ordered to begin a siege. Preliminary bombardments were performed for three days by mangonels from a nearby hilltop with casualties on both sides. A direct Mongol assault on the fourth day is repulsed. The Mongols then used heavier siege engines hurling javelins dipped in burning pitch and set up mangonels all around the fortifications.[11]

In November Kuhrshah sent a message offering his surrender on the condition of the impunity of him and his family. Hülegü's royal decree was sent by Ata-Malik Juvayni, who took it personally to Khurshah, asking for his signature, but Khurshah was hesitant. After several days, Hülegü began another bombardment and on 19 November, Khurshah and his entourage descended from the fortress and announced surrender. The evacuation of the fortress continued until the next day. A small part of the garrison refused to surrender and fought in a last stand in the "qubba" (literally "domed structure"), supposedly a high domed building in the fortress; they were defeated and killed after three days. [11][20][22]

The Nizaris' leadership decision to surrender was apparently influenced by outside scholars such as al-Tusi.[23]

A puzzling aspect of the events for historians is that why Alamut did not attempt to assist their besieged camrades in Maymun-Diz.[24]

Surrender of Alamut

Khurshah instructed all Nizari castles of the Rusbar valley to surrender, evacuate, and dismantle their forts. All castles (around forty) subsequently surrendered, except Alamut (under Muqaddam al-Din) and Lambsar, possibly because their commanders thought the Imam issued orders under duress and was practicing a sort of taqiyya. Despite the small size of the fortress and its garrison, Alamut was stone-built (unlike Maymun-Diz), well-provisioned, and featured a reliable water supply. However, the Nizari faith demands the faithful absolute obedience to the Imam in all circumstances. Hülegü surrounded Alamut with his army, and Khurshah unsuccessfully attempted to persuade its commander to surrender. Hülegü left a large force under Balaghai to besiege Alamut, and himself together with Khurshah set out to besiege Lambsar. Muqaddam al-Din eventually surrendered after a few days in December 1256.[11][22]

Juvayni describes the difficulty by which the Mongols dismantled the plastered walls and lead-covered ramparts of Alamut. The Mongols had to set fire to the buildings and then destroy them piece by piece. He also notes the extensive chambers, galleries, and deep tanks, which were used to store wine, vinegar, honey, and other goods; during their pillage, one man was reportedly almost drowned in a honey store.[11]

Juvayni saved "copies of the Qur'an and other choice books" as well as "astronomical instruments such as kursis (part of an astrolabe), armillary spheres, complete and partial astrolabes, and others", and burned the other books "which related to their heresy and error". He also picked Hasan Sabbah's biography, Sargudhasht-i Bābā Sayyidinā (Persian: سرگذشت بابا سیدنا), which interested him, but he claims he burnt it after reading it. He has extensively cited its contents in his Tarikh-i Jahangushay.[11]

Juvayni has noted the impregnability and self-sufficiency of Alamut and other Nizari fortresses. Rashid al-Din similarly writes of the good fortune of Mongols in their war against the Nizaris.[23]

Massacres of the Nizaris and aftermath

By 1256, Hülegü almost eliminated the Persian Nizaris as an independent military force.[25] Khurshah was then taken to Qazvin where he sent messages to the Syrian Nizari stronghold instructing them to surrender, but they did not act, believing that the Imam was acting under duress.[11] As his position became intolerable, Khurshah asked Hülegü to be allowed to go meet Möngke in Mongolia, promising that he would persuade the remaining Ismaili fortresses to surrender. Möngke rebuked him after visiting him in Karakoram, Mongolia, due to his failure to hand over Lambsar and Gerdkuh, and ordered his return to his homeland. In the way, he and his small retinue were executed by their Mongol escort. Möngke meanwhile issued a general massacre of all Nizari Ismailis, including all of Khurshah's family as well as the garrisons.[11][2] Khurshah's relatives who were kept at Qazvin were killed by Qaraqai Bitikchi, while Ötegü-China summoned the Nizaris of Quhistan to gatherings and slaughtered about 12,000 people. Möngke's order reflects an earlier order by Chingiz Khan.[23] Around 100,000 people are estimated to have been killed.[11]

Hülegü then moved with the bulk of his army to Azerbaijan, officially established his own khanate (the Ilkhanate), and then sacked Baghdad in 1258.[25]

As the centralized government of the Nizaris was disestablished, the Nizaris either were killed or had abandoned their traditional strongholds. Many of them migrated to Afghanistan, Badakhshan, and Sindh. Little is known about the history of the Ismailis in this stage, until two centuries later, when they again began to grow as scattered communities under regional da'is in Iran, Afghanistan, Badakhshan, Syria, and India.[2] The Nizaris of Syria were tolerated by the Bahri Mamluks and held a few castles under Mamluk suzerainty. The Mamluks may have employed Nizari fedais against their own enemies, notably the attempted assassination of the Crusading Prince Edward of England in 1271.[26]

Resistance by Nizaris in Persia was still ongoing in some forts, notably Lambsar, Gerdkuh, and several forts in Quhistan.[27][25] Lambsar fell in January 1257 after a cholera outbreak.[28] Gerdkuh resisted much longer. The Mongols had built permanent structures and houses around this fortress, the ruins of which, together with two types of stones used for Nizari and Mongol mangonels, still remains today.[23] On 15 December 1270, during the reign of Abaqa, the garrison of Gerdkuh surrendered from want of clothing. It was thirteen years after the fall of Alamut, and seventeen years after its first siege by Kitbuqa. The Mongols killed the surviving garrison but did not destroy the fortress.[23] In the same year, an unsuccessful assassination attempt of Juvayni is attributed to the Nizaris, who had earlier spoken of their total annihilation.[29]

In 1275, a Nizari force under a son of Khurshah and a descendant of the Khwarezmian dynasty recaptured the Alamut Castle, but the Mongols reclaimed it a year later.[30][29] The Nizaris finally re-established their religious order and political power at the village of Anjudan, where they are recorded to be active in the 14-15th century.

References

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. pp. 418–420. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Daftary, Farhad. "The Mediaeval Ismailis of the Iranian Lands | The Institute of Ismaili Studies". www.iis.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- Daftary, Farhad (2012). Historical Dictionary of the Ismailis. Scarecrow Press. p. xxx. ISBN 978-0-8108-6164-0.

- Waterson, James (2008-10-30). "1: A House Divided: The Origins of the Ismaili Assassins". The Ismaili Assassins: A History of Medieval Murder. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-78346-150-9.

- Fiennes, Ranulph (2019-10-17). The Elite: The Story of Special Forces – From Ancient Sparta to the War on Terror. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4711-5664-9.

- Brown, Daniel W. (2011-08-24). A New Introduction to Islam (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-4443-5772-1.

- Willey, Peter (2005). Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 177–182. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- "Magiran | روزنامه ایران (1392/07/02): ناگفته هایی از عظیم ترین دژ فردوس". www.magiran.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- "Magiran | روزنامه شرق (1390/01/15): قلعه ای در دل کوه فردوس". www.magiran.com. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- Komaroff, Linda (2006). Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan. BRILL. p. 123. ISBN 978-90-474-1857-3.

- Willey, Peter (2005). Eagle's Nest: Ismaili Castles in Iran and Syria. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 75–85. ISBN 978-1-85043-464-1.

- Dashdondog, Bayarsaikhan (2010). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). BRILL. p. 125. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- 霍渥斯 (1888). History of the Mongols: From the 9th to the 19th Century ... 文殿閣書莊. pp. 95–97.

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Sneath, David; Kaplonski, Christopher (2010). The History of Mongolia (3 Vols.). Global Oriental. p. 329. ISBN 978-90-04-21635-8.

- Broadbridge, Anne F. (2018). Women and the Making of the Mongol Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-108-42489-9.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (1977). Ismāʻīlī contributions to Islamic culture. Imperial Iranian Academy of Philosophy. p. 20.

- Kwanten, Luc (1979). Imperial Nomads: A History of Central Asia, 500-1500. Leicester University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7185-1180-7.

- Howorth, Sir Henry Hoyle (1888). History of the Mongols: The Mongols of Persia. B. Franklin. pp. 104–109.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, J. A.; Boyle, John Andrew; Frye, Richard Nelson (1968). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-521-06936-6.

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Daftary, Farhad (1992). The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-521-42974-0.

- Nicolle, David; Hook, Richard (1998). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. Brockhampton Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-86019-407-8.

- "IL-KHANIDS i. DYNASTIC HISTORY – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- Nicolle, David (2007). Crusader Warfare: Muslims, Mongols and the struggle against the Crusades. Hambledon Continuum. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84725-146-6.

- Franzius, Enno (1969). History of the Order of Assassins. [Illustr.] Funk & Wagnalls. p. 138.

- Bretschneider, E. (1910). Mediæval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: pt. 3. Explanation of a Mongol-Chinese mediæval map of central and western Asia. pt. 4 Chinese intercourse with the countries of central and western Asia during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Company, Limited. p. 110.

- Virani, Shafique N.; Virani, Assistant Professor Departments of Historical Studies and the Study of Religion Shafique N. (2007). The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: A History of Survival, a Search for Salvation. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-531173-0.

- Wasserman, James (2001). The Templars and the Assassins: The Militia of Heaven. Simon and Schuster. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-59477-873-5.