Red Turban Rebellions

The Red Turban Rebellions (Chinese: 紅巾起義; pinyin: Hóngjīn Qǐyì) were uprisings against the Yuan dynasty between 1351 and 1368, eventually leading to the overthrow of Mongol rule in China.

| Red Turban Rebellions | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

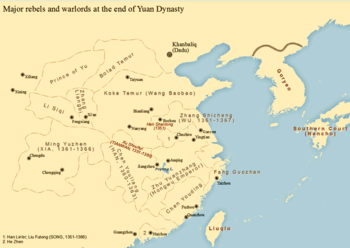

Distribution of major rebel forces and Yuan warlords | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

|

Principality of Liang (Yunnan) Goryeo |

Northern Red Turban rebels: Song dynasty (1351-1366) Wu (1361-1367) Ming dynasty (from 1368) |

Southern Red Turban rebels: Tianwan dynasty (1351-1360) Chen Han dynasty (1360-1363) Ming Xia dynasty (1361-1366) | Dazhou Kingdom (1354-1367) |

Other warlords Fujian Muslim rebels (1357-1366) Shaanxi warlords | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

Toghon Temür Bolud Temür Köke Temür (Wang Baobao) |

Han Shantong † Guo Zixing Zhu Yuanzhang |

Peng Yingyu Ming Yuzhen Ming Sheng | Zhang Shicheng |

Fang Guozhen Bolad Temür Zhang Liangbi Li Siqi Törebeg Kong Xing | ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||||

| Chinese, Mongol and Asud Alan cavalry | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

Causes

Since the 1340s, Yuan dynasty experienced problems. The Yellow River flooded constantly, and other natural disasters also occurred. At the same time the Yuan dynasty required considerable military expenditure to maintain its vast empire.[1]

The Black Death also contributed to the birth of the movement. Other groups or religious sects made an effort to undermine the power of the last Yuan rulers; these religious movements often warned of impending doom. Decline of agriculture, plague and cold weather hit China, spurring the armed rebellion.[2] In Hebei, 9 out of 10 were killed by the Black Death when Toghon Temür was enthroned in 1333. Two out of three people in China had died of the plague by 1351.[3]

Rebellions

The Red Turban Army (紅巾軍) was originally started by Guo Zixing (郭子興) and other followers of the White Lotus to resist the Mongols. The name "Red Turban" was used because of their tradition of using red banners and wearing red turbans to distinguish themselves.

These rebellions began on a sporadic basis, first on the coast of Zhejiang when Fang Guozhen and his men assaulted a group of Yuan officials. After that, the White Lotus led by Han Shantong north of the Yellow River became the centre of anti-Mongol sentiment. Red Turban armies in Liaodong invaded Goryeo in 1359 and 1360, briefly occupying Pyongyang (1359) and Kaesong (1360), but were eventually defeated both times.

In 1351 the society plotted an armed rebellion, but it was disclosed and Han Shantong was arrested and executed by the Yuan government. After his death, Liu Futong (劉福通), a prominent member of the White Lotus, assisted Han's son, Han Lin'er (韓林兒), in succeeding his father and establishing the Red Turban Army. After that, several other Chinese rebels in the south of the Yangtze revolted under the name of the Southern Red Turbans. Among the key leaders of the Southern Red Turbans were Xu Shouhui and Chen Youliang. The rebellion was also supported by the leadership of Peng Yingyu (彭瑩玉; 1338) and Zou Pusheng (鄒普勝; 1351).

Conclusion

One of the more significant Red Turban leaders was Zhu Yuanzhang. At first, he followed Guo Zixing, and in fact married Guo's adopted daughter. After Guo's death, Zhu was seen as his successor and took over Guo's army. Zhu Yuanzhang came from Fengyang and his band of followers such as Xu Da, Chang Yuchun, Tang He, Lan Yu and Mu Ying were known as the "Fengyang mafia"[4][5][6] later becoming nobles in the Ming dynasty.

Between 1356 and 1367 Zhu began a series of military campaigns seeking to defeat his opponents in the Red Turbans. At first he nominally supported Han Lin'er to stabilize his northern frontier. Then he defeated rivals Chen Youliang, Zhang Shicheng and Fang Guozhen one by one. After rising to dominance, he drowned Han Lin'er. Calling to overthrow the Mongols and restore the Chinese, Zhu gained popular support.

In 1368 Zhu Yuanzhang proclaimed himself emperor in Yingtian, historically known as the Hongwu Emperor of the Ming dynasty. The next year the Ming army captured Dadu, and the rule of the Mongol Yuan dynasty was officially over. China was once again under the Chinese rule.

Historical records commonly portray the Red Turban Army as dealing with captive Yuan officials and soldiers with considerable violence. In his work on violence in rural China, William T. Rowe writes:[7]

The Red Army brutally killed every Yuan official it could lay its hands on: in one instance, the Yuan shi reports, the army flayed an official alive and cut out his stomach. The Red Army was equally merciless toward captured Yuan soldiers: according to contemporary observer Liu Renben, Tianwan troops dealt with these demonized enemies by "placing them in shackles, poking them with knives, binding them with cloth, putting sacks over their heads, and parading them around accompanied by drum-beating and derisive chants."

Following the victory, Zhu Yuanzhang ordered mass relocations across China. People from Shanxi w:zh:洪洞大槐树 were deported into other provinces in northern China including Hebei, Henan and Shandong which had been devastated by plague and famine.[8][9][10][11][12] Zhu Yuanzhang moved people from Shandong, Guangdong, Hebei, Shanxi and Lake Taihu to settle in his hometown of Fengyang, around 500,000 people in 1367. Guizhou and Yunnan were colonized by soldiers from Anhui, Suzhou and Shanghai from Nanjing numbering 100,000. Sichuan was resettled by people from Hubei and Hunan, Hubei and Hunan were resettled by people from Jiangxi and Henan, Shandong, Beijing, Hezhou and Chuzhou were resettled by people from Shanxi and western Zhejiang while northern Henan and Hebei was resettled by people from Shanxi.[13] The migration has been remembered in legends and novels.[14] Fengyang was resettled by people from southern China[15] and Jiangnan.[16]

In the early Ming dynasty, the population in North and Central China was declining due to wars. In order to increase the population and start the economic recovery of these war-torn areas, the Ming government organized many large-scale forced mass migration to the area. People were moved from Shanxi province, which had been less affected by the wars, to the war-torn, less-populated area of North and Central China. The people were ordered to move to a location near "the tree" (大槐树), and prepare themselves for the family migration. The Shanxi Xiao family were part of this group of "immigrants under the tree" (在大槐树下集中移民), which were moved to the modern provinces of Henan, Shandong, Hebei, Beijing, Tianjin, Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Anhui, Jiangsu, Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi, Liaoning, Jilin, Heilongjiang, Shanxi and other places. Today, the Xiao family still has memorial tablets dedicated to their ancestors among the "immigrants under the tree" at the fourth cabinet of the memorial hall at the "large tree roots memorial garden" (大槐树寻根祭祖园祭祖堂四号供橱).

See also

References

- Yuan Dynasty: Ancient China Dynasties, paragraph 3.

- Brook, Timothy (1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0520221543.

- Chua, Amy (2009). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance--and Why They Fall. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 123. ISBN 978-0307472458.

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry (2011). Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. University of Washington Press. pp. 22, 64. ISBN 978-0295800226.

- Adshead, S. A. M. (2016). China In World History (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 175. ISBN 978-1349237852.

- China in World History, Third Edition (3, illustrated ed.). Springer. 2016. p. 175. ISBN 978-1349624096.

- Rowe, William. Crimson Rain: Seven Centuries of Violence in a Chinese County. 2006. p. 53

- "Land of fairy tales". China Daily (Hong Kong ). 23 Jun 2012.

- "Chinese Mass Migrations: Past, Present & Future". China Simplified. January 22, 2016.

- Brook, Timothy (1999). The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China (illustrated, reprint ed.). University of California Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-0520221543.

- Chinese Geography and Environment, Volume 1, Issue 2 - Volume 3, Issue 2. M.E. Sharpe, Incorporated. 1988. pp. 11, 12.

- Li, Nan (March 2018). "The Long‐Term Consequences of Cultural Distance on Migration: Historical Evidence from China". Australian Economic History Review. Economic History Society of Australia and New Zealand and John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd. 58 (1): 2–35. doi:10.1111/aehr.12134.

- Wang, Fang (2016). Geo-Architecture and Landscape in China's Geographic and Historic Context: Volume 1 Geo-Architecture Wandering in the Landscape (illustrated ed.). Springer. p. 275. ISBN 978-9811004834.

- Yan, Lianke (2012). Lenin's Kisses: A Novel. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 978-0802193940.

- He, H. (2016). Governance, Social Organisation and Reform in Rural China: Case Studies from Anhui Province (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-1137484697.

- Lu, Hanchao (2005). Street Criers: A Cultural History of Chinese Beggars (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Pres. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0804751483.

External links