Marine ecosystem

Marine ecosystems are the largest of Earth's aquatic ecosystems and are distinguished by waters that have a high salt content. These systems contrast with freshwater ecosystems, which have a lower salt content. Marine waters cover more than 70% of the surface of the Earth and account for more than 97% of Earth's water supply[1][2] and 90% of habitable space on Earth.[3] Marine ecosystems include nearshore systems, such as the salt marshes, mudflats, seagrass meadows, mangroves, rocky intertidal systems and coral reefs. They also extend outwards from the coast to include offshore systems, such as the surface ocean, pelagic ocean waters, the deep sea, oceanic hydrothermal vents, and the sea floor. Marine ecosystems are characterized by the biological community of organisms that they are associated with and their physical environment.

Types

Salt marsh

Salt marshes are a transition from the ocean to the land, where fresh and saltwater mix.[4] The soil in these marshes is often made up of mud and a layer of organic material called peat. Peat is characterized as waterlogged and root-filled decomposing plant matter that often causes low oxygen levels (hypoxia). These hypoxic conditions are caused the growth of bacteria that also give salt marshes the sulfurous smell they are often known for.[5] Salt marshes exist around the world and are needed for healthy ecosystems and a healthy economy. They are extremely productive ecosystems and they provide essential services for more than 75 percent of fishery species and protect shorelines from erosion and flooding.[5] Salt marshes can be generally divided into the high marsh, low marsh, and the upland border. The low marsh is closer to the ocean, with it being flooded at nearly every tide except low tide.[4] The high marsh is located between the low marsh and the upland border and it usually only flooded when higher than usual tides are present.[4] The upland border is the freshwater edge of the marsh and is usually located at elevations slightly higher than the high marsh. This region is usually only flooded under extreme weather conditions and experiences much less waterlogged conditions and salt stress than other areas of the marsh.[4]

Mangroves

Mangroves are trees or shrubs that grow in low-oxygen soil near coastlines in tropical or subtropical latitudes.[6] They are an extremely productive and complex ecosystem that connects the land and sea. Mangroves consist of species that are not necessarily related to each other and are often grouped for the characteristics they share rather than genetic similarity.[7] Because of their proximity to the coast, they have all developed adaptions such as salt excretion and root aeration to live in salty, oxygen-depleted water.[7] Mangroves can often be recognized by their dense tangle of roots that act to protect the coast by reducing erosion from storm surges, currents, wave, and tides.[6] The mangrove ecosystem is also an important source of food for many species as well as excellent at sequestering carbon dioxide from the atmosphere with global mangrove carbon storage is estimated at 34 million metric tons per year.[7]

Intertidal zones

Intertidal zones are the areas that are visible and exposed to air during low tide and covered up by saltwater during high tide.[8] There are four physical divisions of the intertidal zone with each one having its distinct characteristics and wildlife. These divisions are the Spray zone, High intertidal zone, Middle Intertidal zone, and Low intertidal zone. The Spray zone is a damp area that is usually only reached by the ocean and submerged only under high tides or storms. The high intertidal zone is submerged at high tide but remains dry for long periods between high tides.[8] Due to the large variance of conditions possible in this region, it is inhabited by resilient wildlife that can withstand these changes such as barnacles, marine snails, mussels and hermit crabs.[8] Tides flow over the middle intertidal zone two times a day and this zone has a larger variety of wildlife.[8] The low intertidal zone is submerged nearly all the time except during the lowest tides and life is more abundant here due to the protection that the water gives.[8]

Estuaries

Estuaries occur where there is a noticeable change in salinity between saltwater and freshwater sources. This is typically found where rivers meet the ocean or sea. The wildlife found within estuaries is unique as the water in these areas is brackish - a mix of freshwater flowing to the ocean and salty seawater.[9] Other types of estuaries also exist and have similar characteristics as traditional brackish estuaries. The Great Lakes are a prime example. There, river water mixes with lake water and creates freshwater estuaries.[9] Estuaries are extremely productive ecosystems that many humans and animal species rely on for various activities.[10] This can be seen as, of the 32 largest cities in the world, 22 are located on estuaries as they provide many environmental and economic benefits such as crucial habitat for many species, and being economic hubs for many coastal communities.[10] Estuaries also provide essential ecosystem services such as water filtration, habitat protection, erosion control, gas regulation nutrient cycling, and it even gives education, recreation and tourism opportunities to people.[11]

Lagoons

Lagoons are areas that are separated from larger water by natural barriers such as coral reefs or sandbars. There are two types of lagoons, coastal and oceanic/atoll lagoons.[12] A coastal lagoon is, as the definition above, simply a body of water that is separated from the ocean by a barrier. An atoll lagoon is a circular coral reef or several coral islands that surround a lagoon. Atoll lagoons are often much deeper than coastal lagoons.[13] Most lagoons are very shallow meaning that they are greatly affected by changed in precipitation, evaporation and wind. This means that salinity and temperature are widely varied in lagoons and that they can have water that ranges from fresh to hypersaline.[13] Lagoons can be found in on coasts all over the world, on every continent except Antarctica and is an extremely diverse habitat being home to a wide array of species including birds, fish, crabs, plankton and more.[13] Lagoons are also important to the economy as they provide a wide array of ecosystem services in addition to being the home of so many different species. Some of these services include fisheries, nutrient cycling, flood protection, water filtration, and even human tradition.[13]

Coral reefs

Coral reefs are one of the most well-known marine ecosystems in the world, with the largest being the Great Barrier Reef. These reefs are composed of large coral colonies of a variety of species living together. The corals from multiple symbiotic relationships with the organisms around them.[14]

Ecosystem services

addition to providing many benefits to the natural world, marine ecosystems also provide social, economic, and biological ecosystem services to humans. Pelagic marine systems regulate the global climate, contribute to the water cycle, maintain biodiversity, provide food and energy resources, and create opportunities for recreation and tourism.[17] Economically, marine systems support billions of dollars worth of capture fisheries, aquaculture, offshore oil and gas, and trade and shipping.

Ecosystem services fall into multiple categories, including supporting services, provisioning services, regulating services, and cultural services.[18]

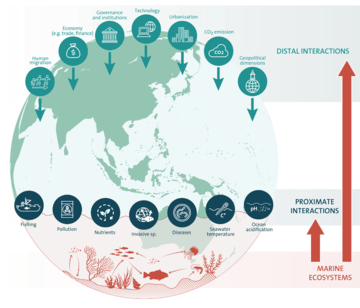

Threats

Although marine ecosystems provide essential ecosystem services, these systems face various threats.[20]

Human exploitation and development

Coastal marine ecosystems experience growing population pressures with nearly 40% of people in the world living within 100 km of the coast.[21] Humans often aggregate near coastal habitats to take advantage of ecosystem services. For example, coastal capture fisheries from mangroves and coral reef habitats are estimated to be worth a minimum of $34 billion per year.[21] Yet, many of these habitats are either marginally protected or not protected. Mangrove area has declined worldwide by more than one-third since 1950,[22] and 60% of the world's coral reefs are now immediately or directly threatened.[23][24] Human development, aquaculture, and industrialization often lead to the destruction, replacement, or degradation of coastal habitats.[21]

Moving offshore, pelagic marine systems are directly threatened by overfishing.[25] Global fisheries landings peaked in the late 1980s, but are now declining, despite increasing fishing effort.[17] Fish biomass and average trophic level of fisheries landing are decreasing, leading to declines in marine biodiversity. In particular, local extinctions have led to declines in large, long-lived, slow-growing species, and those that have narrow geographic ranges.[17] Biodiversity declines can lead to associated declines in ecosystem services. A long-term study reports the decline of 74–92% of catch per unit effort of sharks in Australian coastline from the 1960s to 2010s.[26]

Pollution

- Nutrients[27]

- Sedimentation

- Pathogens

- Toxic substances

- Trash and microplastics

Invasive species

- Global aquarium trade

- Ballast water transport

- Aquaculture

Climate change

- Warming temperatures

- Increased frequency/intensity of storms

- Ocean acidification

- Sea level rise

See also

References

- "Oceanic Institute". www.oceanicinstitute.org. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "Ocean Habitats and Information". 2017-01-05. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "Facts and figures on marine biodiversity | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "What is a Salt Marsh?" (PDF). New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services. 2004.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is a salt marsh?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is a mangrove forest?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- "Mangroves". Smithsonian Ocean. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is the intertidal zone?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is an estuary?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Estuaries, NOS Education Offering". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- "Estuaries". www.crd.bc.ca. 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "What is a lagoon?". oceanservice.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-24.

- Miththapala, Sriyanie (2013). "Lagoons and Estuaries" (PDF). IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- "Corals and Coral Reefs". Ocean Portal | Smithsonian. 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "The Deep Sea". Ocean Portal | Smithsonian. 2012-07-24. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "The Benthic Zone". Ecosystems. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- "Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Marine Systems" (PDF).

- "Ecosystem Services | Mapping Ocean Wealth". oceanwealth.org. Retrieved 2018-03-27.

- Österblom, H., Crona, B.I., Folke, C., Nyström, M. and Troell, M. (2017) "Marine ecosystem science on an intertwined planet". Ecosystems, 20(1): 54–61. doi:10.1007/s10021-016-9998-6

- "Status of and Threat to Coral Reefs | International Coral Reef Initiative". www.icriforum.org. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- "Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Coastal Systems" (PDF).

- Alongi, Daniel M. (September 2002). "Present state and future of the world's mangrove forests". Environmental Conservation. 29 (3): 331–349. doi:10.1017/S0376892902000231. ISSN 1469-4387.

- "Coral Reefs". Ocean Health Index. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Burke, Lauretta Marie (2011). Reefs at Risk Revisited | World Resources Institute. www.wri.org. ISBN 9781569737620. Retrieved 2018-12-01.

- Coll, Marta; Libralato, Simone; Tudela, Sergi; Palomera, Isabel; Pranovi, Fabio (2008-12-10). "Ecosystem Overfishing in the Ocean". PLOS ONE. 3 (12): e3881. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.3881C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003881. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2587707. PMID 19066624.

- Mumby, Peter J.; Mark A. Priest; Brown, Christopher J.; Roff, George (2018-12-13). "Decline of coastal apex shark populations over the past half century". Communications Biology. 1 (1): 223. doi:10.1038/s42003-018-0233-1. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 6292889. PMID 30564744.

- EPA,OW, US (2017-01-30). "Threats to Coral Reefs | US EPA". US EPA.

Further reading

- Barange M, Field JG, Harris RP, Eileen E, Hofmann EE, Perry RI and Werner F (2010) Marine Ecosystems and Global Change Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955802-5

- Boyd IL, Wanless S and Camphuysen CJ (2006) Top predators in marine ecosystems: their role in monitoring and management Volume 12 of Conservation biology series. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84773-5

- Davenport J (2008) Challenges to Marine Ecosystems: Proceedings of the 41st European Marine Biology Symposium Volume 202 of Developments in hydrobiology. ISBN 978-1-4020-8807-0

- Levner E, Linkov I and Proth J (2005) Strategic management of marine ecosystems Springer. Volume 50 of NATO Science Series IV. ISBN 978-1-4020-3158-8

- Mann KH and Lazier JRN (2006) Dynamics of marine ecosystems: biological-physical interactions in the oceans Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-1118-8

- Moustakas A and Karakassis I (2005) "How diverse is aquatic biodiversity research?" Aquatic Ecology, 39: 367–375.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marine ecosystems. |