Biological interaction

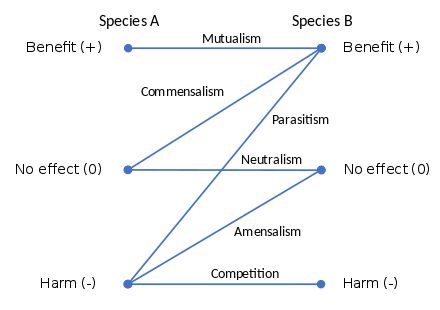

In ecology, a biological interaction is the effect that a pair of organisms living together in a community have on each other. They can be either of the same species (intraspecific interactions), or of different species (interspecific interactions). These effects may be short-term, like pollination and predation, or long-term; both often strongly influence the evolution of the species involved. A long-term interaction is called a symbiosis. Symbioses range from mutualism, beneficial to both partners, to competition, harmful to both partners.[1] Interactions can be indirect, through intermediaries such as shared resources or common enemies. This type of relationship can be shown by net effect based on individual effects on both organisms arising out of relationship.

History

Although biological interactions, more or less individually, were studied earlier, Edward Haskell (1949) gave a integrative approach to the thematic, proposing a classification of "co-actions",[2] later adopted by biologists as "interactions". Close and long-term interactions are described as symbiosis;[lower-alpha 1] symbioses that are mutually beneficial are called mutualistic.[3][4][5]

Short-term interactions

Short-term interactions, including predation and pollination, are extremely important in ecology and evolution. These are short-lived in terms of the duration of a single interaction: a predator kills and eats a prey; a pollinator transfers pollen from one flower to another; but they are extremely durable in terms of their influence on the evolution of both partners. As a result, the partners coevolve.[6][7]

Predation

In predation, one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. Predators are adapted and often highly specialized for hunting, with acute senses such as vision, hearing, or smell. Many predatory animals, both vertebrate and invertebrate, have sharp claws or jaws to grip, kill, and cut up their prey. Other adaptations include stealth and aggressive mimicry that improve hunting efficiency. Predation has a powerful selective effect on prey, causing them to develop antipredator adaptations such as warning coloration, alarm calls and other signals, camouflage and defensive spines and chemicals.[8][9][10] Predation has been a major driver of evolution since at least the Cambrian period.[6]

Over the last several decades, microbiologists have discovered a number of fascinating microbes that survive by their ability to prey upon others. Several of the best examples are members of the genera Bdellovibrio, Vampirococcus, and Daptobacter.

Bdellovibrios are active hunters that are vigorously motile, swimming about looking for susceptible Gram-negative bacterial prey. Upon sensing such a cell, a bdellovibrio cell swims faster until it collides with the prey cell. It then bores a hole through the outer membrane of its prey and enters the periplasmic space. As it grows, it forms a long filament that eventually septates to produce progeny bacteria. Lysis of the prey cell releases new bdellovibrio cells.Bdellovibrios will not attack mammalian cells, and Gram-negative prey bacteria have never been observed to acquire resistance to bdellovibrios.

This has raised interest in the use of these bacteria as a "probiotic" to treat infected wounds. Although this has not yet been tried, one can imagine that with the rise in antibiotic-resistant pathogens, such forms of treatments may be considered viable alternatives.

Pollination

In pollination, pollinators including insects (entomophily), some birds (ornithophily), and some bats, transfer pollen from a male flower part to a female flower part, enabling fertilisation, in return for a reward of pollen or nectar.[11] The partners have coevolved through geological time; in the case of insects and flowering plants, the coevolution has continued for over 100 million years. Insect-pollinated flowers are adapted with shaped structures, bright colours, patterns, scent, nectar, and sticky pollen to attract insects, guide them to pick up and deposit pollen, and reward them for the service. Pollinator insects like bees are adapted to detect flowers by colour, pattern, and scent, to collect and transport pollen (such as with bristles shaped to form pollen baskets on their hind legs), and to collect and process nectar (in the case of honey bees, making and storing honey). The adaptations on each side of the interaction match the adaptations on the other side, and have been shaped by natural selection on their effectiveness of pollination.[7][12][13]

Symbiosis: long-term interactions

The six possible types of symbiosis are mutualism, commensalism, parasitism, neutralism, amensalism, and competition. These are distinguished by the degree of benefit or harm they cause to each partner.

Mutualism

Mutualism is an interaction between two or more species, where species derive a mutual benefit, for example an increased carrying capacity. Similar interactions within a species are known as co-operation. Mutualism may be classified in terms of the closeness of association, the closest being symbiosis, which is often confused with mutualism. One or both species involved in the interaction may be obligate, meaning they cannot survive in the short or long term without the other species. Though mutualism has historically received less attention than other interactions such as predation,[14] it is an important subject in ecology. Examples include cleaning symbiosis, gut flora, Müllerian mimicry, and nitrogen fixation by bacteria in the root nodules of legumes.

Commensalism

Commensalism benefits one organism and the other organism is neither benefited nor harmed. It occurs when one organism takes benefits by interacting with another organism by which the host organism is not affected. A good example is a remora living with a manatee. Remoras feed on the manatee's faeces. The manatee is not affected by this interaction, as the remora does not deplete the manatee's resources.[15]

Parasitism

Parasitism is a relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or in another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life.[16] The parasite either feeds on the host, or, in the case of intestinal parasites, consumes some of its food.[17]

Neutralism

Neutralism (a term introduced by Eugene Odum)[18] describes the relationship between two species that interact but do not affect each other. Examples of true neutralism are virtually impossible to prove; the term is in practice used to describe situations where interactions are negligible or insignificant.[19][20]

Amensalism

Amensalism (a term introduced by Haskell)[21] is an interaction where an organism inflicts harm to another organism without any costs or benefits received by itself.[22] Amensalism describes the adverse effect that one organism has on another organism (figure 32.1). This is a unidirectional process based on the release of a specific compound by one organism that has a negative effect on another. A classic example of amensalism is the microbial production of antibiotics

that can inhibit or kill other, susceptible microorganisms.

A clear case of amensalism is where sheep or cattle trample grass. Whilst the presence of the grass causes negligible detrimental effects to the animal's hoof, the grass suffers from being crushed. Amensalism is often used to describe strongly asymmetrical competitive interactions, such as has been observed between the Spanish ibex and weevils of the genus Timarcha which feed upon the same type of shrub. Whilst the presence of the weevil has almost no influence on food availability, the presence of ibex has an enormous detrimental effect on weevil numbers, as they consume significant quantities of plant matter and incidentally ingest the weevils upon it.[23]

Amensalisms can be quite complex. Attine ants (ants belonging to a New World tribe) are able to take advantage of an interaction between an actinomycete

and a parasitic fungus in the genus Escovopsis. This amensalistic relationship enables the ant to maintain a mutualism with members of another fungal genus, Leucocoprini. Amazingly, these ants cultivate a garden of Leucocoprini fungi for their own nourishment. To prevent the parasitic fungus Escovsis from decimating their fungal garden, the ants also promote the growth of an actinomycete of the genus Pseudonocardia, which produces an antimicrobial compound that inhibits thegrowth of the Escovopsis fungi.

Competition

Competition can be defined as an interaction between organisms or species, in which the fitness of one is lowered by the presence of another. Competition is often for a resource such as food, water, or territory in limited supply, or for access to females for reproduction.[14] Competition among members of the same species is known as intraspecific competition, while competition between individuals of different species is known as interspecific competition. According to the competitive exclusion principle, species less suited to compete for resources should either adapt or die out.[24][25] According to evolutionary theory, this competition within and between species for resources plays a critical role in natural selection.[26]

Notes

- Symbiosis was formerly used to mean a mutualism.

References

- Wootton, JT; Emmerson, M (2005). "Measurement of Interaction Strength in Nature". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 36: 419–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.091704.175535. JSTOR 30033811.

- Haskell, E. F. (1949). A clarification of social science. Main Currents in Modern Thought 7: 45–51.

- Burkholder, P. R. (1952) Cooperation and Conflict among Primitive Organisms. American Scientist, 40, 601-631. link.

- Bronstein, J. L. (2015). The study of mutualism. In: Bronstein, J. L. (ed.). Mutualism. Oxford University Press, Oxford. link.

- Pringle, E. G. (2016). Orienting the Interaction Compass: Resource Availability as a Major Driver of Context Dependence. PLoS Biology, 14(10), e2000891. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.2000891.

- Bengtson, S. (2002). "Origins and early evolution of predation". In Kowalewski, M.; Kelley, P. H. (eds.). The fossil record of predation. The Paleontological Society Papers 8 (PDF). The Paleontological Society. pp. 289–317.

- Lunau, Klaus (2004). "Adaptive radiation and coevolution — pollination biology case studies". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 4 (3): 207–224. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2004.02.002.

- Bar-Yam. "Predator-Prey Relationships". New England Complex Systems Institute. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Predator & Prey: Adaptations" (PDF). Royal Saskatchewan Museum. 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

- Vermeij, Geerat J. (1993). Evolution and Escalation: An Ecological History of Life. Princeton University Press. pp. 11 and passim. ISBN 978-0-691-00080-0.

- "Types of Pollination, Pollinators and Terminology". CropsReview.Com. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Pollan, Michael (2001). The Botany of Desire: A Plant's-eye View of the World. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-7475-6300-6.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Raven, Peter H. (1964). "Butterflies and Plants: A Study in Coevolution". Evolution. 18 (4): 586–608. doi:10.2307/2406212. JSTOR 2406212.

- Begon, M., J.L. Harper and C.R. Townsend. 1996. Ecology: individuals, populations, and communities, Third Edition. Blackwell Science Ltd., Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Williams E, Mignucci, Williams L & Bonde (November 2003). "Echeneid-sirenian associations, with information on sharksucker diet". Journal of Fish Biology. 5 (63): 1176–1183. Retrieved 17 June 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Poulin, Robert (2007). Evolutionary Ecology of Parasites. Princeton University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-691-12085-0.

- Martin, Bradford D.; Schwab, Ernest (2013). "Current usage of symbiosis and associated terminology". International Journal of Biology. 5 (1): 32–45. doi:10.5539/ijb.v5n1p32.

- Toepfer, G. "Neutralism". In: BioConcepts. link.

- (Morris et al., 2013)

- Lidicker W. Z. (1979). "A Clarification of Interactions in Ecological Systems". BioScience. 29 (8): 475–477. doi:10.2307/1307540. JSTOR 1307540. Researchgate.

- Toepfer, G. "Amensalism". In: BioConcepts. link.

- Willey, Joanne M.; Sherwood, Linda M.; Woolverton, Cristopher J. (2013). Prescott's Microbiology (9th ed.). pp. 713–38. ISBN 978-0-07-751066-4.

- Gómez, José M.; González-Megías, Adela (2002). "Asymmetrical interactions between ungulates and phytophagous insects: Being different matters". Ecology. 83 (1): 203–11. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0203:AIBUAP]2.0.CO;2.

- Hardin, Garrett (1960). "The competitive exclusion principle" (PDF). Science. 131 (3409): 1292–1297. doi:10.1126/science.131.3409.1292. PMID 14399717.

- Pocheville, Arnaud (2015). "The Ecological Niche: History and Recent Controversies". In Heams, Thomas; Huneman, Philippe; Lecointre, Guillaume; et al. (eds.). Handbook of Evolutionary Thinking in the Sciences. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 547–586. ISBN 978-94-017-9014-7.

- Sahney, Sarda; Benton, Michael J.; Ferry, Paul A. (23 August 2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land". Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ecological interactions. |

- Snow, B. K. & Snow, D. W. (1988). Birds and berries: a study of an ecological interaction. Poyser, London ISBN 0-85661-049-6