Marine debris

Marine debris, also known as marine litter, is human-created waste that has deliberately or accidentally been released in a sea or ocean. Floating oceanic debris tends to accumulate at the center of gyres and on coastlines,[1] frequently washing aground, when it is known as beach litter or tidewrack. Deliberate disposal of wastes at sea is called ocean dumping. Naturally occurring debris, such as driftwood, are also present.

With the increasing use of plastic, human influence has become an issue as many types of (petrochemical) plastics do not biodegrade.[2] Waterborne plastic poses a serious threat to fish, seabirds, marine reptiles, and marine mammals, as well as to boats and coasts.[3] Dumping, container spillages, litter washed into storm drains and waterways and wind-blown landfill waste all contribute to this problem.

In efforts to prevent and mediate marine debris and pollutants, laws and policies have been adopted internationally. Depending on relevance to the issues and various levels of contribution, some countries have introduced more specified protection policies.

Types of debris

Researchers classify debris as either land- or ocean-based; in 1991, the United Nations Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Pollution estimated that up to 80% of the pollution was land-based,[4] with the remaining 20% originating from catastrophic events or maritime sources.[5] More recent studies have found that more than half of plastic debris found on Korean shores is ocean-based.[6]

A wide variety of man-made objects can become marine debris; plastic bags, balloons, buoys, rope, medical waste, glass and plastic bottles, cigarette stubs, cigarette lighters, beverage cans, polystyrene, lost fishing line and nets, and various wastes from cruise ships and oil rigs are among the items commonly found to have washed ashore. Six pack rings, in particular, are considered emblematic of the problem.[7]

The US military used ocean dumping for unused weapons and bombs, including ordinary bombs, UXO, landmines and chemical weapons from at least 1919 until 1970.[8] Millions of pounds of ordnance were disposed of in the Gulf of Mexico and off the coasts of at least 16 states, from New Jersey to Hawaii (although these, of course, do not wash up onshore, and the US is not the only country who has practiced this).[9]

Eighty percent of marine debris is plastic.[10] Plastics accumulate because they typically do not biodegrade as many other substances do. They photodegrade on exposure to sunlight, although they do so only under dry conditions, as water inhibits photolysis.[11] In a 2014 study using computer models, scientists from the group 5 Gyres, estimated 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic weighing 269,000 tons were dispersed in oceans in similar amount in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres.[12]

Ghost nets

.jpg)

Fishing nets left or lost in the ocean by fishermen – ghost nets – can entangle fish, dolphins, sea turtles, sharks, dugongs, crocodiles, seabirds, crabs, and other creatures. These nets restrict movement, causing starvation, laceration and infection, and, in animals that breathe air, suffocation.[13]

Plastic

8.8 million metric tons of plastic waste are dumped in the world's oceans each year. Asia was the leading source of mismanaged plastic waste, with China alone accounting for 2.4 million metric tons.[14]

The trade in plastic waste has been identified as the main cause of marine litter.[lower-alpha 1] Countries importing the waste plastics often lack the capacity to process all the material. As a result, the United Nations has imposed a ban on waste plastic trade unless it meets certain criteria.[lower-alpha 2]

Plastic waste has reached all the world's oceans. This plastic pollution harms an estimated 100,000 sea turtles and marine mammals and 1,000,000 sea creatures each year.[16] Larger plastics (called "macroplastics") such as plastic shopping bags can clog the digestive tracts of larger animals when consumed by them[17] and can cause starvation through restricting the movement of food, or by filling the stomach and tricking the animal into thinking it is full. Microplastics on the other hand harm smaller marine life. For example, pelagic plastic pieces in the center of our ocean’s gyres outnumber live marine plankton, and are passed up the food chain to reach all marine life.[18] A 1994 study of the seabed using trawl nets in the North-Western Mediterranean around the coasts of Spain, France, and Italy reported mean concentrations of debris of 1,935 items per square kilometre. Plastic debris accounted for 77%, of which 93% was plastic bags.[17]

Nurdles

Nurdles, also known as "mermaids' tears", are plastic pellets, typically under five millimetres in diameter, that are a major component of marine debris. They are a raw material in plastics manufacturing, and enter the natural environment when spilled. Weathering produces ever smaller pieces. Nurdles strongly resemble fish eggs.[19]

Deep-sea debris

Litter, made from diverse materials that are denser than surface water (such as glasses, metals and some plastics), have been found to spread over the floor of seas and open oceans, where it can become entangled in corals and interfere with other sea-floor life, or even become buried under sediment, making clean-up extremely difficult, especially due to the wide area of its dispersal compared to shipwrecks.[20] Research performed by MBARI found items including plastic bags below 2000 m depth off the west coast of North America and around Hawaii.[21]

A recent study surveyed four separate locations to represent a wider range of marine habitats at depths varying from 1100-5000m. Three of the four locations had identifiable amounts of microplastics present in the top 1cm layer of sediment. Core samples were taken from each spot and had their microplastics filtered out of the normal sediment. The plastic components were identified using micro-Raman spectroscopy; the results showed man-made pigments commonly used in the plastic industry.[22]

Sources of debris

The 10 largest emitters of oceanic plastic pollution worldwide are, from the most to the least, China, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Egypt, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Bangladesh,[23] largely through the rivers Yangtze, Indus, Yellow, Hai, Nile, Ganges, Pearl, Amur, Niger, and the Mekong, and accounting for "90 percent of all the plastic that reaches the world's oceans."[24][25]

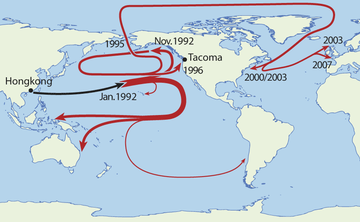

An estimated 10,000 containers at sea each year are lost by container ships, usually during storms.[26] One spillage occurred in the Pacific Ocean in 1992, when thousands of rubber ducks and other toys (now known as the "Friendly Floatees") went overboard during a storm. The toys have since been found all over the world, providing a better understanding of ocean currents. Similar incidents have happened before, such as when Hansa Carrier dropped 21 containers (with one notably containing buoyant Nike shoes).[27] In 2007, MSC Napoli beached in the English Channel, dropping hundreds of containers, most of which washed up on the Jurassic Coast, a World Heritage Site.[28]

In Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia, 52% of items were generated by recreational use of an urban park, 14% from sewage disposal and only 7% from shipping and fishing activities.[29] Around four fifths[30] of oceanic debris is from rubbish blown onto the water from landfills, and urban runoff.[3]

Some studies show that marine debris may be dominant in particular locations. For example, a 2016 study of Aruba found that debris found the windward side of the island was predominantly marine debris from distant sources.[31] In 2013, debris from six beaches in Korea was collected and analyzed: 56% was found to be "ocean-based" and 44% "land-based".[32]

In the 1987 Syringe Tide, medical waste washed ashore in New Jersey after having been blown from Fresh Kills Landfill.[33][34] On the remote sub-Antarctic island of South Georgia, fishing-related debris, approximately 80% plastics, are responsible for the entanglement of large numbers of Antarctic fur seals.[35]

Marine litter is even found on the floor of the Arctic ocean.[36]

Five subtropical gyres

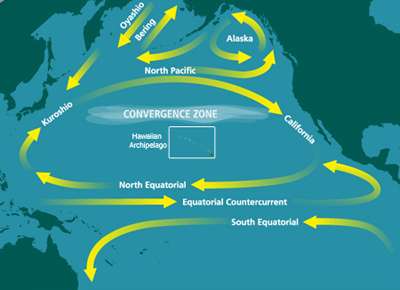

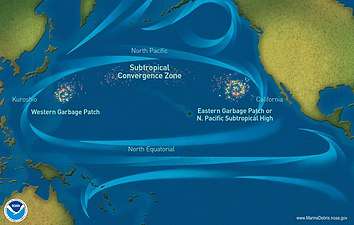

Despite the abundance of plastic being deposited into the ocean, the distribution across the oceans was relatively unknown. Appropriately, a study was conducted in 2014 to model an accurate representation of the current magnitude of surface level pollution within the oceans. The project was concluded with the identification of five areas across all the oceans where the majority of plastic was being concentrated.

The researchers collected a total of 3070 samples across the world to identify hot spots of surface level plastic pollution. The pattern of distribution closely mirrored models of oceanic currents with the North Pacific Gyre, or Great Pacific Garbage Patch, being the highest density of plastic accumulation. The other four gyres include the North Atlantic Gyre between the North America and Africa, the South Atlantic Gyre located between eastern South America and the tip of Africa, the South Pacific Gyre located west of South America, and the Indian Ocean Gyre found east of south Africa listed in order of decreasing size.[37]

Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Once waterborne, debris becomes mobile. Flotsam can be blown by the wind, or follow the flow of ocean currents, often ending up in the middle of oceanic gyres where currents are weakest. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is one such example of this, comprising a vast region of the North Pacific Ocean rich with anthropogenic wastes. Estimated to be double the size of Texas, the area contains more than 3 million tons of plastic.[38]The combination of two developed countries disposing of their plastic into the neighboring ocean is the source of blame. The eastern coast of Asia maintains the highest population density of any coast consisting of a third of the world's coastal population.

Patches may be large enough to be viewed by satellite. For example, when the Malaysian Flight MH370 disappeared in 2014, satellites were scanning the oceans surface for any sign of it, and instead of finding debris from the plane they came across floating garbage.[40] The gyre contains approximately six pounds of plastic for every pound of plankton.[41]

The oceans may contain as much as one hundred million tons of plastic.[30] It is estimated that each garbage patch in the ocean have up to one million tons of trash swirling around in them, sometimes extending down to around one hundred feet below the surface.[42] Some items that have been extracted from these garbage patches are: a drum of hazardous chemicals, plastic hangers, tires, cable cords, a ton of tangled netting etc.

Over 40% of oceans are classified as subtropical gyres, a quarter of the planet’s surface area has become an accumulator of floating plastic debris.

Islands situated within gyres frequently have coastlines flooded by waste that washes ashore; prime examples are Midway[43] and Hawaii.[44] Clean-up teams around the world patrol beaches to attack this environmental threat.[43]

More than 37 million pieces of plastic debris have accumulated on Henderson Island, a remote Pitcairn island in the South Pacific, reported to be the highest density of debris reported anywhere in the world, yet the trash accounts for only 1.98 seconds’ worth of the annual global production of plastic.[45]

Environmental impact

.jpg)

Many animals that live on or in the sea consume flotsam by mistake, as it often looks similar to their natural prey.[46] Bulky plastic debris may become permanently lodged in the digestive tracts of these animals, blocking the passage of food and causing death through starvation or infection.[47] Tiny floating plastic particles also resemble zooplankton, which can lead filter feeders to consume them and cause them to enter the ocean food chain. In samples taken from the North Pacific Gyre in 1999 by the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, the mass of plastic exceeded that of zooplankton by a factor of six.[10][48]

Toxic additives used in plastic manufacturing can leach into their surroundings when exposed to water. Waterborne hydrophobic pollutants collect and magnify on the surface of plastic debris,[30] thus making plastic more deadly in the ocean than it would be on land.[10] Hydrophobic contaminants bioaccumulate in fatty tissues, biomagnifying up the food chain and pressuring apex predators and humans.[49] Some plastic additives disrupt the endocrine system when consumed; others can suppress the immune system or decrease reproductive rates.[48] Bisphenol A (BPA) is a famous example of a plasticizer produced in high volumes for food packing from where it can leach into food, leading to human exposure. As an estrogen and glucocorticoid receptor agonist, BPA is interfering with the endocrine system and is associated with increased fat in rodents.[50]

The hydrophobic nature of plastic surfaces stimulates rapid formation of biofilms,[51] which support a wide range of metabolic activities, and drive succession of other micro- and macro-organisms.[52]

Concern among experts has grown since the 2000s that some organisms have adapted to live on[53] floating plastic debris, allowing them to disperse with ocean currents and thus potentially become invasive species in distant ecosystems.[54] Research in 2014 in the waters around Australia[51] confirmed a wealth of such colonists, even on tiny flakes, and also found thriving ocean bacteria eating into the plastic to form pits and grooves. These researchers showed that "plastic biodegradation is occurring at the sea surface" through the action of bacteria, and noted that this is congruent with a new body of research on such bacteria. Their finding is also congruent with the other major research undertaken[55] in 2014, which sought to answer the riddle of the overall lack of build up of floating plastic in the oceans, despite ongoing high levels of dumping. Plastics were found as microfibres in core samples drilled from sediments at the bottom of the deep ocean. The cause of such widespread deep sea deposition has yet to be determined.

Not all anthropogenic artifacts placed in the oceans are harmful. Iron and concrete structures typically do little damage to the environment because they generally sink to the bottom and become immobile, and at shallow depths they can even provide scaffolding for artificial reefs. Ships and subway cars have been deliberately sunk for that purpose.[56]

Additionally, hermit crabs have been known to use pieces of beach litter as a shell when they cannot find an actual seashell of the size they need.[57]

The ingestion of plastic by marine organisms has now been established at full ocean depth. Microplastic was found in the stomachs of hadal amphipods sampled from the Japan, Izu-Bonin, Mariana, Kermadec, New Hebrides and the Peru-Chile trenches. The amphipods from the Marina Trench were sampled at 10,890 m and all contained microfibres.[58]

Debris removal

Techniques for collecting and removing marine (or riverine) debris include the use of debris skimmer boats (pictured). Devices such as these can be used where floating debris presents a danger to navigation. For example, the US Army Corps of Engineers removes 90 tons of "drifting material" from San Francisco Bay every month. The Corps has been doing this work since 1942, when a seaplane carrying Admiral Chester W. Nimitz collided with a piece of floating debris and sank, costing the life of its pilot.[59] The Ocean cleanup has also created a vessel for cleaning up riverine debris, called Interceptor. Once debris becomes "beach litter", collection by hand and specialized beach-cleaning machines are used to gather the debris.

There are also projects that stimulate fishing boats to remove any litter they accidentally fish up while fishing for fish.[60]

Elsewhere, "trash traps" are installed on small rivers to capture waterborne debris before it reaches the sea. For example, South Australia's Adelaide operates a number of such traps, known as "trash racks" or "gross pollutant traps" on the Torrens River, which flows (during the wet season) into Gulf St Vincent.[61]

In lakes or near the coast, manual removal can also be used. Project AWARE for example promotes the idea of letting dive clubs clean up litter, for example as a diving exercise.[62]

On the sea, the removal of artificial debris (i.e. plastics) is still in its infancy. However some projects have been started which used ships with nets (Kaisei and New Horizon) to catch some plastics, primarily for research purposes. There is also Bluebird Marine System's SeaVax which was solar- and wind-powered and had an onboard shredder and cargo hold.[63][64] The Sea Cleaners' Manta ship is similar in concept.[65]

Another method to gather artificial litter has been proposed by The Ocean Cleanup's Boyan Slat. He suggested using platforms with arms to gather the debris, situated inside the current of gyres.[66] The SAS Ocean Phoenix ship is somewhat similar in design.[67][68]

Another issue is that removing marine debris from our oceans can potentially cause more harm than good. Cleaning up micro-plastics could also accidentally take out plankton, which are the main lower level food group for the marine food chain and over half of the photosynthesis on earth.[40] One of the most efficient and cost effective ways to help reduce the amount of plastic entering our oceans is to not participate in using single-use plastics, avoid plastic bottled drinks such as water bottles, use reusable shopping bags, and to buy products with reusable packaging.[69]

Once a year there is a diving marine debris removal operation in Scapa Flow in the Orkneys, run by Ghost Fishing UK, funded by World Animal Protection and Fat Face Foundation.[70][71][72]

Laws and treaties

The ocean is a global common, so negative externalities of marine debris are not usually experienced by the producer. In the 1950s, the importance of government intervention with marine pollution protocol was recognized at the First Conference on the Law of the Sea.[73]

Ocean dumping is controlled by international law, including:

- The London Convention (1972) – a United Nations agreement to control ocean dumping[74] This Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter consisted of twenty two articles addressing expectations of contracting parties.[75] The three annexes defined many compounds, substances, and materials that are unacceptable to deposit into the ocean.[75] Examples of such matter include: mercury compounds, lead, cyanides, and radioactive wastes.[75]

- MARPOL 73/78 – a convention designed to minimize pollution of the seas, including dumping, oil and exhaust pollution[76] The original MARPOL convention did not consider dumping from ships, but was revised in 1978 to include restrictions on marine vessels.[77]

- UNCLOS- signed in 1982, but effective in 1994, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea emphasized the importance of protecting the entire ocean and not only specified coastal regions.[73] UNCLOS enforced restrictions on pollution, including a stress on land-based sources.[73]

Australian law

One of the earliest anti-dumping laws was Australia's Beaches, Fishing Grounds and Sea Routes Protection Act 1932, which prohibited the discharge of "garbage, rubbish, ashes or organic refuse" from "any vessel in Australian waters" without prior written permission from the federal government. It also required permission for scuttling.[78] The act was passed in response to large amounts of garbage washing up on the beaches of Sydney and Newcastle from vessels outside the reach of local governments and the New South Wales government.[79] It was repealed and replaced by the Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981, which gave effect to the London Convention.[80]

European law

In 1972 and 1974, conventions were held in Oslo and Paris respectively, and resulted in the passing of the OSPAR Convention, an international treaty controlling marine pollution in the north-east Atlantic Ocean.[81] The Barcelona Convention protects the Mediterranean Sea. The Water Framework Directive of 2000 is a European Union directive committing EU member states to free inland and coastal waters from human influence.[82] In the United Kingdom, the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 is designed to "ensure clean healthy, safe, productive and biologically diverse oceans and seas, by putting in place better systems for delivering sustainable development of marine and coastal environment".[83] In 2019, the EU parliament voted for an EU-wide ban on single-use plastic products such as plastic straws, cutlery, plates, and drink containers, polystyrene food and drink containers, plastic drink stirrers and plastic carrier bags and cotton buds. The law will take effect in 2021.[84]

United States law

In the waters of the United States, there have been many observed consequences of pollution including: hypoxic zones, harmful agal blooms, and threatened species.[85] In 1972, the United States Congress passed the Ocean Dumping Act, giving the Environmental Protection Agency power to monitor and regulate the dumping of sewage sludge, industrial waste, radioactive waste and biohazardous materials into the nation's territorial waters.[86] The Act was amended sixteen years later to include medical wastes.[87] It is illegal to dispose of any plastic in US waters.[3]

Ownership

Property law, admiralty law and the law of the sea may be of relevance when lost, mislaid, and abandoned property is found at sea. Salvage law rewards salvors for risking life and property to rescue the property of another from peril. On land the distinction between deliberate and accidental loss led to the concept of a "treasure trove". In the United Kingdom, shipwrecked goods should be reported to a Receiver of Wreck, and if identifiable, they should be returned to their rightful owner.[88]

Activism

A large number of groups and individuals are active in preventing or educating about marine debris. For example, 5 Gyres is an organization aimed at reducing plastics pollution in the oceans, and was one of two organizations that recently researched the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Heal the Bay is another organization, focusing on protecting California's Santa Monica Bay, by sponsoring beach cleanup programs along with other activities. Marina DeBris is an artist focusing most of her recent work on educating people about beach trash. Interactive sites like Adrift[89] demonstrate where marine plastic is carried, over time, on the worlds ocean currents.

On 11 April 2013 in order to create awareness, artist Maria Cristina Finucci founded The Garbage patch state at UNESCO[90] –Paris in front of Director General Irina Bokova. First of a series of events under the patronage of UNESCO and of Italian Ministry of the Environment.[91]

Forty-eight plastics manufacturers from 25 countries, are members of the Global Plastic Associations for solutions on Marine Litter, have made the pledge to help prevent marine debris and to encourage recycling.[40]

Mitigation

Marine debris is a problem created by all of us, not only those in coastal regions.[92] Ocean debris can come from as far away as Nebraska. The places that see the most damage are often not the places that produce the pollution. For ocean pollution, much of the trash may come from inland states, where people may never see the ocean and thus may never put any thought into protecting it. The problem continues to grow in tandem with plastics usage and disposal. Steps can be taken to prevent the movement of inland plastics into the oceans.

Plastic debris from inland states come from two main sources: ordinary litter and materials from open dumps and landfills that blow or wash away to inland waterways and wastewater outflows. The refuse finds its way from inland waterways, rivers, streams and lakes to the ocean. Though ocean and coastal area cleanups are important, it is crucial to address plastic waste that originates from inland and landlocked states.[93][94]

At the systems level, there are various ways to reduce the amount of debris entering our waterways:

- Improve waste transportation to and from sites by utilizing closed container storage and shipping

- Restrict open waste facilities near waterways

- Promote the use of Refuse-derived fuels. Used plastic with low residual value often do not get recycled and are more likely to leak into the ocean.[95] However, turning these unwanted plastics that would otherwise stay in landfills into refuse-derived fuels allows for further use; they can be used as supplement fuels at power plants

- Improve recovery rates for plastic (in 2012, the United States generated 11.46 million tons of plastic waste, of which only 6.7% was recovered[96]

- Adapt Extended Producer Responsibility strategies to make producers responsible for product management when products and their packaging become waste; encourage reusable product design to minimize negative impacts on the environment.[97]

- Ban the use of cigarette filters and establish a deposit-system for e-cigarettes (similar to the one used for propane canisters)[98]

As consumers, there are things we can do to help reduce the amount of plastic entering our waterways:[94]

- Reduce usage of single-use plastics such as plastic bags, straws, water bottles, utensils and coffee cups by replacing them with reusable products such as reusable bags, metal straws, reusable water bottles, bamboo toothbrushes and reusable coffee cups

- Avoid microbeads, which are found in face scrubs, toothpastes and body washes

- Participate in a river or lake beach clean up

- Support municipality bans and other legislation regulating single-use plastics and plastic waste

- If you smoke, avoid using filtered cigarettes, and dispose of e-cigarettes responsibly[98]

- Continue to recycle, recycle, recycle

Though the awareness of inland ocean conservation debris mitigation seems to be small compared to coastal states, some organizations in the United States are already working to improve this. The Colorado Ocean Coalition was formed in 2011 with the goal of impressing upon inland citizens that they don’t need to see the ocean to care about its health. It has since grown beyond one state and now forms the Inland Ocean Coalition, with the mission of promoting knowledge and awareness of how inland states contribute to pollution of the ocean, aiming to shatter the ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality that often applies in this region.

“Those who live among mountains, rivers and inland cities have a direct impact on the cycle of life in the ocean,” reads the IOCO website. "The changes we need to make to address the largest threats facing our seas—lowering carbon emissions, reducing trash and pollution, eating sustainable seafood, safeguarding watersheds, promoting marine protected areas (MPAs)—can happen from anywhere in the world.”

This organization has chapters in many inland US states and promotes programs like watershed cleanups, youth-centered education, and decreasing the use of plastic.

Plastic-to-fuel conversion strategy

The Clean Oceans Project (TCOP) promotes conversion of the plastic waste into valuable liquid fuels, including gasoline, diesel and kerosene, using plastic-to-fuel conversion technology developed by Blest Co. Ltd., a Japanese environmental engineering company.[99][100][101][102] TCOP plans to educate local communities and create a financial incentive for them to recycle plastic, keep their shorelines clean, and minimize plastic waste.[100][103]

In 2019, a research group led scientists of Washington State University found a way to turn plastic waste products into jet fuel.[104]

Also, the company "Recycling Technologies", has come up with a simple process that can convert plastic waste to an oil called Plaxx. The company is led by a team of engineers from the university of Warwick.[105][106]

Other companies working on a system for converting plastic waste to fuel include GRT Group and OMV.[107][108][109]

See also

- Citizen Science

- Flotsam and jetsam

- Kamilo Beach

- Marina DeBris

- Marine pollution

- National Cleanup Day

- Plastic pollution

- Plastic-eating organisms

- Project Kaisei

- Waste management

- World Cleanup Day

Notes

- "Campaigners have identified the global trade in plastic waste as a main culprit in marine litter, because the industrialised world has for years been shipping much of its plastic “recyclables” to developing countries, which often lack the capacity to process all the material."[15]

- "The new UN rules will effectively prevent the US and EU from exporting any mixed plastic waste, as well plastics that are contaminated or unrecyclable — a move that will slash the global plastic waste trade when it comes into effect in January 2021."[15]

References

- Gary Strieker (28 July 1998). "Pollution invades small Pacific island". CNN. Archived from the original on 31 December 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Graham, Rachel (10 July 2019). "Euronews Living | Watch: Italy's answer to the problem with plastic". living.

- "Facts about marine debris". US NOAA. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- Sheavly, S. B.; Register, K. M. (2007). "Marine Debris & Plastics: Environmental Concerns, Sources, Impacts and Solutions". Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 15 (4): 301–305. doi:10.1007/s10924-007-0074-3.

- Weiss, K.R. (2017). "The pileup of plastic debris is more than ugly ocean litter". Knowable Magazine. doi:10.1146/knowable-120717-211902. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017.

- Jang, Yong Chang; Lee, Jongmyoung; Hong, Sunwook; Lee, Jong Su; Shim, Won Joon; Song, Young Kyoung (6 July 2014). "Sources of plastic marine debris on beaches of Korea: More from the ocean than the land". Ocean Science Journal. 49 (2): 151–162. Bibcode:2014OSJ....49..151J. doi:10.1007/s12601-014-0015-8.

- Cecil Adams (16 July 1999). "Should you cut up six-pack rings so they don't choke sea birds?". The Straight Dope. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- Edgar B. Herwick III (29 July 2015). "Explosive Beach Objects-- Just Another Example Of Massachusetts' Charm". WGBH news. PBS. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- "Military Ordinance [sic] Dumped in Gulf of Mexico". Maritime Executive. 3 August 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- Alan Weisman (2007). The World Without Us. St. Martin's Thomas Dunne Books. pp. 112–128. ISBN 978-0-312-34729-1.

- Alan Weisman (Summer 2007). "Polymers Are Forever". Orion magazine. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- "5 Trillion Pieces of Ocean Trash Found, But Fewer Particles Than Expected". 13 December 2014. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- "'Ghost fishing' killing seabirds". BBC News. 28 June 2007. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Robert Lee Hotz (13 February 2015). "Asia Leads World in Dumping Plastic in Seas". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015.

- Clive Cookson 2019.

- "A Ban on Plastic Bags Will Save the Lives of California's Endangered Leatherback Sea Turtles". Sea Turtle Restoration Project. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010.

- "Marine Litter: An analytical overview" (PDF). United Nations Environment Programme. 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- Moore, C.J; Moore, S.L; Leecaster, M.K; Weisberg, S.B (December 2001). "A Comparison of Plastic and Plankton in the North Pacific Central Gyre". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 42 (12): 1297–1300. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00114-X. PMID 11827116.

- Ayre, Maggie (7 December 2006). "Plastics 'poisoning world's seas'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Goodman, Alexa J.; Walker, Tony R.; Brown, Craig J.; Wilson, Brittany R.; Gazzola, Vicki; Sameoto, Jessica A. (November 2019). "Benthic marine debris in the Bay of Fundy, eastern Canada: Spatial distribution and categorization using seafloor video footage". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 150: 110722. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110722.

- "MBARI News Release: MBARI research shows where trash accumulates in the deep sea". Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. 2013. Archived from the original on 7 July 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Van Cauwenberghe, Lisbeth; Vanreusel, Ann; Mees, Jan; Janssen, Colin R. (1 November 2013). "Microplastic pollution in deep-sea sediments". Environmental Pollution. 182: 495–499. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2013.08.013. ISSN 0269-7491.

- Jambeck, Jenna R.; Geyer, Roland; Wilcox, Chris (12 February 2015). "Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean" (PDF). Science. 347 (6223): 768–71. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..768J. doi:10.1126/science.1260352. PMID 25678662. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Christian Schmidt; Tobias Krauth; Stephan Wagner (11 October 2017). "Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–12253. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. PMID 29019247.

The 10 top-ranked rivers transport 88–95% of the global load into the sea

- Harald Franzen (30 November 2017). "Almost all plastic in the ocean comes from just 10 rivers". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

It turns out that about 90 percent of all the plastic that reaches the world's oceans gets flushed through just 10 rivers: The Yangtze, the Indus, Yellow River, Hai River, the Nile, the Ganges, Pearl River, Amur River, the Niger, and the Mekong (in that order).

- Janice Podsada (19 June 2001). "Lost Sea Cargo: Beach Bounty or Junk?". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Marsha Walton (28 May 2003). "How sneakers, toys and hockey gear help ocean science". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- "Scavengers take washed-up goods". BBC News. 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on 9 February 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Walker, T.R.; Grant, J.; Archambault, M-C. (2006). "Accumulation of marine debris on an intertidal beach in an urban park (Halifax Harbour, Nova Scotia)" (PDF). Water Quality Research Journal of Canada. 41 (3): 256–262. doi:10.2166/wqrj.2006.029.

- "Plastic Debris: from Rivers to Sea" (PDF). Algalita Marine Research Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- Scisciolo, Tobia (2016). "Beach debris on Aruba, Southern Caribbean: Attribution to local land-based and distal marine-based sources". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 106 (–2): 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.03.039. PMID 27039956.

- Yong, C (2013). "Sources of plastic marine debris on beaches of Korea: More from the ocean than the land". Ocean Science Journal. 49 (2): 151–162. Bibcode:2014OSJ....49..151J. doi:10.1007/s12601-014-0015-8.

- Alfonso Narvaez (8 December 1987). "New York City to Pay Jersey Town $1 Million Over Shore Pollution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 March 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- "A Summary of the Proposed Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan". New York-New Jersey Harbor Estuary Program. February 1995. Archived from the original on 24 May 2005. Retrieved 25 June 2008.

- Walker, T. R.; Reid, K.; Arnould, J. P. Y.; Croxall, J. P. (1997), "Marine debris surveys at Bird Island, South Georgia 1990–1995", Marine Pollution Bulletin, 34 (1): 61–65, doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00053-7.

- "Plastic trash invades arctic seafloor". Archived from the original on 25 October 2012.

- Cózar, Andrés; Echevarría, Fidel; González-Gordillo, J. Ignacio; Irigoien, Xabier; Úbeda, Bárbara; Hernández-León, Santiago; Palma, Álvaro T.; Navarro, Sandra; García-de-Lomas, Juan; Ruiz, Andrea; Fernández-de-Puelles, María L. (15 July 2014). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (28): 10239–10244. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110239C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- "Congress acts to clean up the ocean - A garbage patch in the Pacific is at least triple the size of Texas, but some estimates put it larger than the continental United States". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 5 October 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Debris Division – Office of Response and Restoration. NOAA. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Parker, Laura. "With Millions of Tons of Plastic in Oceans, More Scientists Studying Impact." National Geographic. National Geographic Society, 13 June 2014. Web. 3 April 2016.

- "Great Pacific garbage patch: Plastic turning vast area of ocean into ecological nightmare". Santa Barbara News-Press. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- Matsumura, Satsuki; Nasu, Keiichi (1997). "Distribution of Floating Debris in the North Pacific Ocean: Sighting Surveys 1986–1991". Marine Debris. Springer Series on Environmental Management. pp. 15–24. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-8486-1_3. ISBN 978-1-4613-8488-5.

- Shukman, David (26 March 2008). "New 'battle of Midway' over plastic". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 March 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Wells, Matt (11 June 2007). "Plastic blights Hawaii's beaches". BBC News. Archived from the original on 31 March 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- "Millions Of Pieces Of Plastic Are Piling Up On An Otherwise Pristine Pacific Island". npr.org. Archived from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Kenneth R. Weiss (2 August 2006). "Plague of Plastic Chokes the Seas". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 23 September 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2008.

- Charles Moore (November 2003). "Across the Pacific Ocean, plastics, plastics, everywhere". Natural History. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- "Plastics and Marine Debris". Algalita Marine Research Foundation. 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- Engler, Richard E. (20 November 2012). "The Complex Interaction between Marine Debris and Toxic Chemicals in the Ocean". Environmental Science & Technology. 46 (22): 12302–12315. Bibcode:2012EnST...4612302E. doi:10.1021/es3027105. PMID 23088563.

- Wassenaar, Pim Nicolaas Hubertus; Trasande, Leonardo; Legler, Juliette (3 October 2017). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Early-Life Exposure to Bisphenol A and Obesity-Related Outcomes in Rodents". Environmental Health Perspectives. 125 (10): 106001. doi:10.1289/EHP1233. PMC 5933326. PMID 28982642.

- Reisser, Julia; Shaw, Jeremy; Hallegraeff, Gustaaf; Proietti, Maira; Barnes, David K. A; Thums, Michele; Wilcox, Chris; Hardesty, Britta Denise; Pattiaratchi, Charitha (18 June 2014). "Millimeter-Sized Marine Plastics: A New Pelagic Habitat for Microorganisms and Invertebrates". PLoS ONE. 9 (6): e100289. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j0289R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100289. PMC 4062529. PMID 24941218.

- Davey, M. E.; O'toole, G. A. (1 December 2000). "Microbial Biofilms: from Ecology to Molecular Genetics". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 64 (4): 847–867. doi:10.1128/mmbr.64.4.847-867.2000. PMC 99016. PMID 11104821.

- "Ocean Debris: Habitat for Some, Havoc for Environment". National Geographic. 23 April 2007. Archived from the original on 7 August 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Rubbish menaces Antarctic species". BBC News. 24 April 2002. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 1 August 2008.

- "Where Has All the (Sea Trash) Plastic Gone?". National Geographic. 18 December 2014. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- Ron Hess; Denis Rushworth; Michael Hynes; John Peters (2 August 2006). "Chapter 5: Reefing" (PDF). Disposal Options for Ships. Rand Corporation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 3 May 2008.

- Miller, Shawn (19 October 2014). "Crabs With Beach Trash Homes – Okinawa, Japan". Okinawa Nature Photography. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- Jamieson, A. J.; Brooks, L. S. R.; Reid, W. D. K.; Piertney, S. B.; Narayanaswamy, B. E.; Linley, T. D. (27 February 2019). "Microplastics and synthetic particles ingested by deep-sea amphipods in six of the deepest marine ecosystems on Earth". Royal Society Open Science. 6 (2): 180667. Bibcode:2019RSOS....680667J. doi:10.1098/rsos.180667. PMC 6408374. PMID 30891254.

- "Debris collection onsite after Bay Bridge struck". US Army Corps of Engineers. Archived from the original on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- "Fishing For Litter". www.fishingforlitter.org.uk.

- "Trash Racks". Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2009.

- "10 Tips for Divers to Protect the Ocean Planet". Archived from the original on 23 September 2014.

- "Solar powered SeaVax hoover concept to clean up the oceans". The International Institute of Marine Surveying (IIMS). 14 March 2016.

- "Solar-Powered Vacuum Could Suck Up 24,000 Tons of Ocean Plastic Every Year". EcoWatch. 19 February 2016.

- "Yvan Bourgnon : «Au large, le Manta pourra ramasser 600 m3 de déchets plastiques»". Libération.fr. 23 April 2018.

- "Methods for collecting plastic litter at sea". MarineDebris.Info. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013.

- "The Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Sierra Club. 6 December 2016.

- Poizat, Christophe J. (3 May 2016). "OFFICIAL LAUNCH OF OCEAN PHOENIX PROJECT". Medium.

- Wabnitz, Colette; Nichols, Wallace J. (2010). "Plastic pollution: An ocean emergency". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 129: 1–4.

- Daily Telegraph 28 September 2017, page 31

- "Lost fishing gear being recovered from Scapa Flow - The Orcadian Online". orcadian.co.uk. 25 September 2017. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Crowley. "GHOST FISHING UK TO BE CHARGED FOR CLEANUPS". divemagazine.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Leous, Justin P.; Parry, Neal B. (2005). "Who is Responsible for Marine Debris? The International Politics of Cleaning Our Oceans". Journal of International Affairs. 59 (1): 257–269. JSTOR 24358243.

- "London Convention". US EPA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter". The American Journal of International Law. 67 (3): 626–636. 1973. doi:10.2307/2199200. JSTOR 2199200.

- "International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL)". www.imo.org. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- Tharpes, Yvonne L. (1989). "International Environmental Law: Turning the Tide on Marine Pollution". The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review. 20 (3): 579–614. JSTOR 40176192.

- "Beaches, Fishing Grounds and Sea Routes Protection Act 1932". Federal Register of Legislation.

- Caroline Ford (2014). Sydney Beaches: A History. NewSouth. p. 230. ISBN 9781742246840.

- "Environment Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981". Federal Register of Legislation.

- "The OSPAR Convention". OSPAR Commission. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Directive 2000/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2000 establishing a framework for Community action in the field of water policy". EurLex. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009". UK Defra. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- "EU parliament approves ban on single use plastics". phys.org.

- Craig, R. (2005). "Protecting International Marine Biodiversity: International Treaties and National Systems of Marine Protected Areas". Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law. 20 (2): 333–369. JSTOR 42842976.

- "Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act of 1972" (PDF). US Senate. 29 December 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Ocean Dumping Ban Act of 1988". US EPA. 21 November 1988. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Can you keep ship-wrecked goods?". BBC News. 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- "Home". PlasticAdrift.org. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "The garbage patch territory turns into a new state". UNESCO Office in Venice. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- "Rifiuti diventano stato, Unesco riconosce 'Garbage Patch'" [Waste becomes state, UNESCO recognizes 'Garbage Patch']. Siti (in Italian). Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- Chow, Lorraine (29 June 2016). "80% Of Ocean Plastic Comes From Land-Based Sources, New Report Finds". EcoWatch.

- Tibbetts, John H. (April 2015). "Managing Marine Plastic Pollution: Policy Initiatives to Address Wayward Waste". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (4): A90-3. doi:10.1289/ehp.123-A90. PMC 4384192. PMID 25830293.

- "7 Ways To Reduce Ocean Plastic Pollution Today". www.oceanicsociety.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- Stemming the tide: Land-based strategies for a plastic-free ocean (pp. 1-48, Rep.). (2015). McKinsey Center for Business and Environment.

- "Municipal Solid Waste Generation, Recycling, and Disposal in the United States: Facts and Figures for 2012" (PDF). EPA.

- Nash, Jennifer; Bosso, Christopher (April 2013). "Extended Producer Responsibility in the United States". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 17 (2): 175–185. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00572.x.

- "Cigarette butts are toxic plastic pollution. Should they be banned?". Environment. 9 August 2019.

- Mosko, Sarah. "Mid-Ocean Plastics Cleanup Schemes: Too Little Too Late?". E-The Environmental Magazine. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- "Jim Holm: The Clean Oceans Project". TEDxGramercy. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- Hamel, Jessi (20 April 2011). "From Trash to Fuel". Santa Cruz Good Times. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- West, Amy E. (January 2012). "Santa Cruz nonprofit hopes to make fuel from ocean-based plastic". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "The Response". The Clean Oceans Project. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Research group finds way to turn plastic waste products into jet fuel". phys.org.

- "SCRA Spinout Case Study - Recycling Technologies". warwick.ac.uk.

- Herreria, Carla (8 June 2017). "3 Incredible Inventions That Are Cleaning Our Oceans". HuffPost.

- "GRT Solution for Today".

- "ReOil: Getting crude oil back out of plastic". www.omv.comhttps.

- "OMV reveals plastic waste to synthetic crude oil pilot". 23 September 2018.

Sources

- Clive Cookson, Leslie Hook (2019), Millions of pieces of plastic waste found on remote island chain, Financial Times, retrieved 31 December 2019

External links

![]()

- United Nations Environment Programme Marine Litter Publications

- UNEP Year Book 2011: Emerging Issues in Our Global Environment Plastic debris, pages 21–34. ISBN 978-92-807-3101-9.

- NOAA Marine Debris Program – US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Marine Debris Abatement – US Environmental Protection Agency

- Marine Research, Education and Restoration – Algalita Marine Research Foundation

- UK Marine Conservation Society

- Harmful Marine Debris – Australian Government

- The trash vortex – Greenpeace

- High Seas GhostNet Survey – US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Social & Economic Costs of Marine Debris – NOAA Economics

- Tiny Plastic Bits Too Small To See Are Destroying The Oceans, Business Insider

- Ghost net remediation program - NASA, NOAA and ATI collaborating to detect ghost nets

- Ocean Plastic. What is it & Just how big is the problem? - Flynn Product Design