Chemotroph

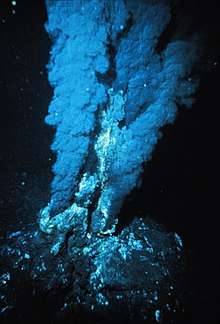

Chemotrophs are organisms that obtain energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments.[1] These molecules can be organic (chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic (chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phototrophs, which use solar energy. Chemotrophs can be either autotrophic or heterotrophic. Chemotrophs are found in ocean floors where sunlight cannot reach them because they are not dependent on solar energy. Ocean floors often contain underwater volcanos that can provide heat as a substitute for sunlight's warmth.

Chemoautotroph

Chemoautotrophs (or chemotrophic autotroph) (Greek: Chemo (χημεία) = chemical, auto (εαυτός) = self, troph (τροφή) = nourishment), in addition to deriving energy from chemical reactions, synthesize all necessary organic compounds from carbon dioxide. Chemoautotrophs can use inorganic electron sources such as hydrogen sulfide, elemental sulfur, ferrous iron, molecular hydrogen, and ammonia or organic sources. Most chemoautotrophs are extremophiles, bacteria or archaea that live in hostile environments (such as deep sea vents) and are the primary producers in such ecosystems. Chemoautotrophs generally fall into several groups: methanogens, halophiles, sulfur oxidizers and reducers, nitrifiers, anammox bacteria, and thermoacidophiles. An example of one of these prokaryotes would be Sulfolobus. Chemolithotrophic growth can be dramatically fast, such as Hydrogenovibrio crunogenus with a doubling time around one hour.[2][3]

The term "chemosynthesis", coined in 1897 by Wilhelm Pfeffer, originally was defined as the energy production by oxidation of inorganic substances in association with autotrophy—what would be named today as chemolithoautotrophy. Later, the term would include also the chemoorganoautotrophy, that is, it can be seen as a synonym of chemoautotrophy.[4][5]

Chemoheterotroph

Chemoheterotrophs (or chemotrophic heterotrophs) (Gr: Chemo (χημία) = chemical, hetero (ἕτερος) = (an)other, troph (τροφιά) = nourishment) are unable to fix carbon to form their own organic compounds. Chemoheterotrophs can be chemolithoheterotrophs, utilizing inorganic electron sources such as sulfur, or chemoorganoheterotrophs, utilizing organic electron sources such as carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins.[6][7][8][9] Most animals and fungi are examples of chemoheterotrophs, obtaining most of their energy from O2.[10]

Iron- and manganese-oxidizing bacteria

In the deep oceans, iron-oxidizing bacteria derive their energy needs by oxidizing ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+). The electron conserved from this reaction reduces the respiratory chain and can be thus used in the synthesis of ATP by forward electron transport or NADH by reverse electron transport, replacing or augmenting traditional phototrophism.

- In general, iron-oxidizing bacteria can exist only in areas with high ferrous iron concentrations, such as new lava beds or areas of hydrothermal activity. Most of the ocean is devoid of ferrous iron, due to both the oxidative effect of dissolved oxygen in the water and the tendency of bacteria to take up the iron.

- Lava beds supply bacteria with ferrous iron straight from the Earth's mantle, but only newly formed igneous rocks have high enough levels of ferrous iron. In addition, because oxygen is necessary for the reaction, these bacteria are much more common in the upper ocean, where oxygen is more abundant.

- What is still unknown is how exactly iron bacteria extract iron from rock. It is accepted that some mechanism exists that eats away at the rock, perhaps through specialized enzymes or compounds that bring more FeO to the surface. It has been long debated about how much of the weathering of the rock is due to biotic components and how much can be attributed to abiotic components.

- Hydrothermal vents also release large quantities of dissolved iron into the deep ocean, allowing bacteria to survive. In addition, the high thermal gradient around vent systems means a wide variety of bacteria can coexist, each with its own specialized temperature niche.

- Regardless of the catalytic method used, chemoautotrophic bacteria provide a significant but frequently overlooked food source for deep sea ecosystems - which otherwise receive limited sunlight and organic nutrients.

Manganese-oxidizing bacteria also make use of igneous lava rocks in much the same way; by oxidizing manganous manganese (Mn2+) into manganic (Mn4+) manganese. Manganese is more scarce than iron oceanic crust, but is much easier for bacteria to extract from igneous glass. In addition, each manganese oxidation donates two electrons to the cell versus one for each iron oxidation, though the amount of ATP or NADH that can be synthesised in couple to these reactions varies with pH and specific reaction thermodynamics in terms of how much of a Gibbs free energy change there is during the oxidation reactions versus the energy change required for the formation of ATP or NADH, all of which vary with concentration, pH etc. Much still remains unknown about manganese-oxidizing bacteria because they have not been cultured and documented to any great extent.

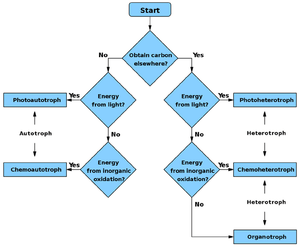

Flowchart

- Autotroph

- Chemoautotroph

- Photoautotroph

- Heterotroph

- Chemoheterotroph

- Photoheterotroph

See also

- Chemosynthesis

- Lithotroph

- RISE project Expedition that discovered high temperature vent communities

Notes

- Chang, Kenneth (12 September 2016). "Visions of Life on Mars in Earth's Depths". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Dobrinski, K. P. (2005). "The Carbon-Concentrating Mechanism of the Hydrothermal Vent Chemolithoautotroph Thiomicrospira crunogena". Journal of Bacteriology. 187 (16): 5761–5766. doi:10.1128/JB.187.16.5761-5766.2005. PMC 1196061. PMID 16077123.

- Rich Boden, Kathleen M. Scott, J. Williams, S. Russel, K. Antonen, Alexander W. Rae, Lee P. Hutt (June 2017). "An evaluation of Thiomicrospira, Hydrogenovibrio and Thioalkalimicrobium: reclassification of four species of Thiomicrospira to each Thiomicrorhabdus gen. nov. and Hydrogenovibrio, and reclassification of all four species of Thioalkalimicrobium to Thiomicrospira". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 67 (5): 1140–1151. doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.001855. PMID 28581925.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kelly, D. P.; Wood, A. P. (2006). "The Chemolithotrophic Prokaryotes". The Prokaryotes. New York: Springer. pp. 441–456. doi:10.1007/0-387-30742-7_15.

- Schlegel, H. G. (1975). "Mechanisms of Chemo-Autotrophy" (PDF). In Kinne, O. (ed.). Marine Ecology. Vol. 2, Part I. pp. 9–60. ISBN 0-471-48004-5.

- Davis, Mackenzie Leo; et al. (2004). Principles of environmental engineering and science. 清华大学出版社. p. 133. ISBN 978-7-302-09724-2.

- Lengeler, Joseph W.; Drews, Gerhart; Schlegel, Hans Günter (1999). Biology of the Prokaryotes. Georg Thieme Verlag. p. 238. ISBN 978-3-13-108411-8.

- Dworkin, Martin (2006). The Prokaryotes: Ecophysiology and biochemistry (3rd ed.). Springer. p. 989. ISBN 978-0-387-25492-0.

- Bergey, David Hendricks; Holt, John G. (1994). Bergey's manual of determinative bacteriology (9th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 427. ISBN 978-0-683-00603-2.

- Schmidt-Rohr, K. (2020). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics” ACS Omega 5: 2221-2233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b03352

References

1. Katrina Edwards. Microbiology of a Sediment Pond and the Underlying Young, Cold, Hydrologically Active Ridge Flank. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

2. Coupled Photochemical and Enzymatic Mn(II) Oxidation Pathways of a Planktonic Roseobacter-Like Bacterium Colleen M. Hansel and Chris A. Francis* Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305-2115 Received 28 September 2005/ Accepted 17 February 2006