Bavaria

Bavaria (/bəˈvɛəriə/; German and Bavarian: Bayern [ˈbaɪɐn]), officially the Free State of Bavaria (German and Bavarian: Freistaat Bayern [ˈfʁaɪʃtaːt ˈbaɪɐn]), is a landlocked state of Germany, occupying its southeastern corner. With an area of 70,550.19 square kilometres (27,239.58 sq mi) Bavaria is the largest German state by land area comprising roughly a fifth of the total land area of Germany. With 13 million inhabitants, it is Germany's second-most-populous state after North Rhine-Westphalia. Bavaria's main cities are Munich (its capital and largest city and also the third largest city in Germany[4]), Nuremberg, and Augsburg.

Free State of Bavaria Freistaat Bayern | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: Bayernhymne (German) "Hymn of Bavaria" | |

| |

| Coordinates: 48°46′39″N 11°25′52″E | |

| Country | Germany |

| Capital | Munich |

| Government | |

| • Body | Landtag of Bavaria |

| • Minister-President | Markus Söder (CSU – Christian Social Union of Bavaria) |

| • Governing parties | CSU / FW |

| • Bundesrat votes | 6 (of 69) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 70,550.19 km2 (27,239.58 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 13,076,721 |

| • Density | 185/km2 (480/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Bavarian(s) (English) Bayer (m), Bayerin (f) (German) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | DE-BY |

| GRP (nominal) | €633 billion (2019)[2] |

| GRP per capita | €48,000 (2019) |

| NUTS Region | DE2 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.947[3] very high · 6th of 16 |

| Website | bayern.de |

The history of Bavaria includes its earliest settlement by Iron Age Celtic tribes, followed by the conquests of the Roman Empire in the 1st century BC, when the territory was incorporated into the provinces of Raetia and Noricum. It became a stem duchy in the 6th century AD following the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. It was later incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire, became an independent kingdom, joined the Prussian-led German Empire in 1871 while retaining its title of kingdom, and finally became a state of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949.[5]

Bavaria has a unique culture, largely because of the state's large Catholic plurality and conservative traditions.[6] Bavarians have traditionally been proud of their culture, which includes a language, cuisine, architecture, festivals such as Oktoberfest and elements of Alpine symbolism.[7] The state also has the second largest economy among the German states by GDP figures, giving it a status as a rather wealthy German region.[8]

Modern Bavaria also includes parts of the historical regions of Franconia and Swabia.

History

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1840 | 3,802,515 | — |

| 1871 | 4,292,484 | +0.39% |

| 1900 | 5,414,831 | +0.80% |

| 1910 | 6,451,380 | +1.77% |

| 1939 | 7,084,086 | +0.32% |

| 1950 | 9,184,466 | +2.39% |

| 1961 | 9,515,479 | +0.32% |

| 1970 | 10,479,386 | +1.08% |

| 1987 | 10,902,643 | +0.23% |

| 2011 | 12,397,614 | +0.54% |

| 2018 | 13,076,721 | +0.76% |

| source:[9] 2018 data[1] | ||

Antiquity

The Bavarians emerged in a region north of the Alps, previously inhabited by Celts, which had been part of the Roman provinces of Raetia and Noricum. The Bavarians spoke a Germanic dialect which developed into Old High German during the early Middle Ages, but, unlike other Germanic groups, they probably did not migrate from elsewhere. Rather, they seem to have coalesced out of other groups left behind by the Roman withdrawal late in the 5th century. These peoples may have included the Celtic Boii, some remaining Romans, Marcomanni, Allemanni, Quadi, Thuringians, Goths, Scirians, Rugians, Heruli. The name "Bavarian" ("Baiuvarii") means "Men of Baia" which may indicate Bohemia, the homeland of the Celtic Boii and later of the Marcomanni. They first appear in written sources circa 520. A 17th century Jewish chronicler David Solomon Ganz, citing Cyriacus Spangenberg, claimed that the diocese was named after an ancient Bohemian king, Boiia, in the 14th century BC.[10]

Middle Ages

From about 554 to 788, the house of Agilolfing ruled the Duchy of Bavaria, ending with Tassilo III who was deposed by Charlemagne.[11]

Three early dukes are named in Frankish sources: Garibald I may have been appointed to the office by the Merovingian kings and married the Lombard princess Walderada when the church forbade her to King Chlothar I in 555. Their daughter, Theodelinde, became Queen of the Lombards in northern Italy and Garibald was forced to flee to her when he fell out with his Frankish overlords. Garibald's successor, Tassilo I, tried unsuccessfully to hold the eastern frontier against the expansion of Slavs and Avars around 600. Tassilo's son Garibald II seems to have achieved a balance of power between 610 and 616.[12]

After Garibald II, little is known of the Bavarians until Duke Theodo I, whose reign may have begun as early as 680. From 696 onward, he invited churchmen from the west to organize churches and strengthen Christianity in his duchy. (It is unclear what Bavarian religious life consisted of before this time.) His son, Theudebert, led a decisive Bavarian campaign to intervene in a succession dispute in the Lombard Kingdom in 714, and married his sister Guntrud to the Lombard King Liutprand. At Theodo's death the duchy was divided among his sons, but reunited under his grandson Hugbert.

At Hugbert's death (735) the duchy passed to a distant relative named Odilo, from neighboring Alemannia (modern southwest Germany and northern Switzerland). Odilo issued a law code for Bavaria, completed the process of church organization in partnership with St. Boniface (739), and tried to intervene in Frankish succession disputes by fighting for the claims of the Carolingian Grifo. He was defeated near Augsburg in 743 but continued to rule until his death in 748.[13][14] Saint Boniface completed the people's conversion to Christianity in the early 8th century.

Tassilo III (b. 741 – d. after 796) succeeded his father at the age of eight after an unsuccessful attempt by Grifo to rule Bavaria. He initially ruled under Frankish oversight but began to function independently from 763 onward. He was particularly noted for founding new monasteries and for expanding eastwards, fighting Slavs in the eastern Alps and along the River Danube and colonizing these lands. After 781, however, his cousin Charlemagne began to pressure Tassilo to submit and finally deposed him in 788. The deposition was not entirely legitimate. Dissenters attempted a coup against Charlemagne at Tassilo's old capital of Regensburg in 792, led by his own son Pépin the Hunchback. The king had to drag Tassilo out of imprisonment to formally renounce his rights and titles at the Assembly of Frankfurt in 794. This is the last appearance of Tassilo in the sources, and he probably died a monk. As all of his family were also forced into monasteries, this was the end of the Agilolfing dynasty.

For the next 400 years numerous families held the duchy, rarely for more than three generations. With the revolt of duke Henry the Quarrelsome in 976, Bavaria lost large territories in the south and south east. The territory of Ostarrichi was elevated to a duchy in its own right and given to the Babenberger family. This event marks the founding of Austria.

The last, and one of the most important, of the dukes of Bavaria was Henry the Lion of the house of Welf, founder of Munich, and de facto the second most powerful man in the empire as the ruler of two duchies. When in 1180, Henry the Lion was deposed as Duke of Saxony and Bavaria by his cousin, Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor (a.k.a. "Barbarossa" for his red beard), Bavaria was awarded as fief to the Wittelsbach family, counts palatinate of Schyren ("Scheyern" in modern German). They ruled for 738 years, from 1180 to 1918. The Electorate of the Palatinate by Rhine (Kurpfalz in German) was also acquired by the House of Wittelsbach in 1214, which they would subsequently hold for six centuries.[15]

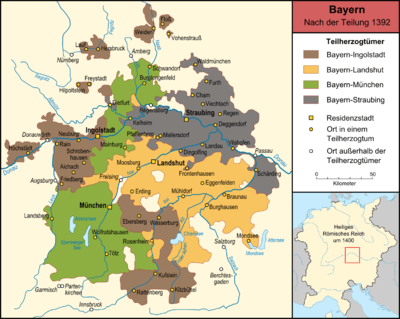

The first of several divisions of the duchy of Bavaria occurred in 1255. With the extinction of the Hohenstaufen in 1268, Swabian territories were acquired by the Wittelsbach dukes. Emperor Louis the Bavarian acquired Brandenburg, Tyrol, Holland and Hainaut for his House but released the Upper Palatinate for the Palatinate branch of the Wittelsbach in 1329. In the 14th and 15th centuries, upper and lower Bavaria were repeatedly subdivided. Four Duchies existed after the division of 1392: Bavaria-Straubing, Bavaria-Landshut, Bavaria-Ingolstadt and Bavaria-Munich. In 1506 with the Landshut War of Succession, the other parts of Bavaria were reunited, and Munich became the sole capital. The country became one of the Jesuit-supported counter-reformation centers.

Electorate of Bavaria

In 1623 the Bavarian duke replaced his relative of the Palatinate branch, the Electorate of the Palatinate in the early days of the Thirty Years' War and acquired the powerful prince-electoral dignity in the Holy Roman Empire, determining its Emperor thence forward, as well as special legal status under the empire's laws.

During the early and mid-18th century the ambitions of the Bavarian prince electors led to several wars with Austria as well as occupations by Austria (War of the Spanish Succession, War of the Austrian Succession with the election of a Wittelsbach emperor instead of a Habsburg). From 1777 onward, and after the younger Bavarian branch of the family had died out with elector Max III Joseph, Bavaria and the Electorate of the Palatinate were governed once again in personal union, now by the Palatinian lines. The new state also comprised the Duchies of Jülich and Berg as these on their part were in personal union with the Palatinate.

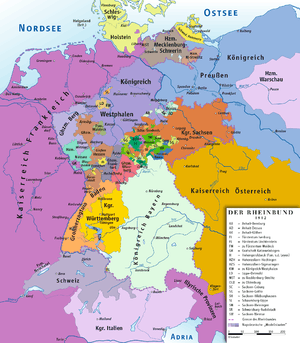

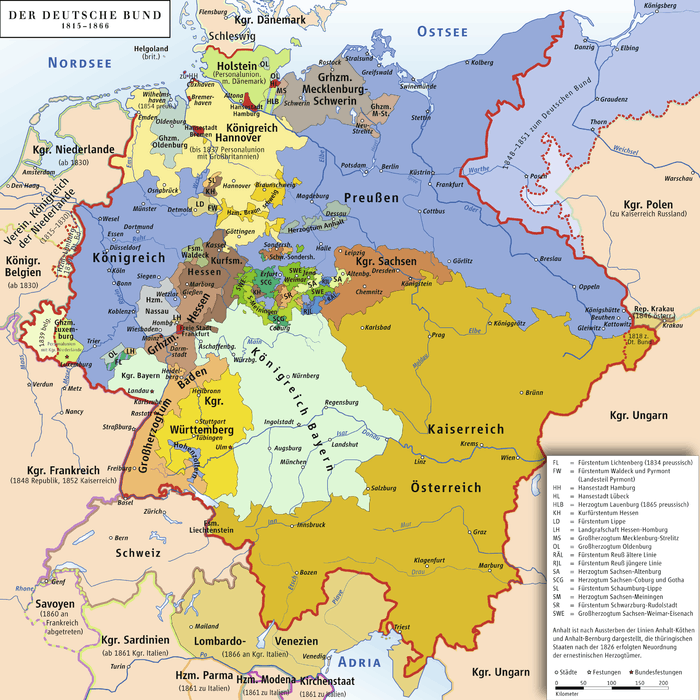

Kingdom of Bavaria

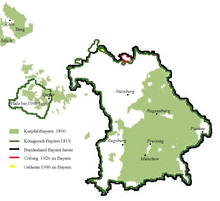

When Napoleon abolished the Holy Roman Empire, Bavaria became a kingdom in 1806 due, in part, to the Confederation of the Rhine.[16] Its area doubled after the Duchy of Jülich was ceded to France, as the Electoral Palatinate was divided between France and the Grand Duchy of Baden. The Duchy of Berg was given to Jerome Bonaparte. Tyrol and Salzburg were temporarily reunited with Bavaria but finally ceded to Austria by the Congress of Vienna. In return Bavaria was allowed to annex the modern-day region of Palatinate to the west of the Rhine and Franconia in 1815. Between 1799 and 1817, the leading minister, Count Montgelas, followed a strict policy of modernisation; he laid the foundations of administrative structures that survived the monarchy and retain core validity in the 21st century. In May 1808 a first constitution was passed by Maximilian I,[17] being modernized in 1818. This second version established a bicameral Parliament with a House of Lords (Kammer der Reichsräte) and a House of Commons (Kammer der Abgeordneten). That constitution was followed until the collapse of the monarchy at the end of World War I.

After the rise of Prussia to power in the early 18th century, Bavaria preserved its independence by playing off the rivalry of Prussia and Austria. Allied to Austria, it was defeated along with Austria in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War and was not incorporated into the North German Confederation of 1867, but the question of German unity was still alive. When France declared war on Prussia in 1870, all the south German states aside from Austria (Baden, Württemberg, Hessen-Darmstadt and Bavaria) joined the Prussian forces and ultimately joined the Federation, which was renamed Deutsches Reich (German Empire) in 1871. Bavaria continued as a monarchy, and it had some special rights within the federation (such as an army, railways, postal service and a diplomatic body of its own) but the diplomatic body postal service railways where later done with by Wilhelm II who declared them illegal and got rid of the diplomatic service first.

Part of the German Empire

.svg.png)

When Bavaria became part of the newly formed German Empire, this action was considered controversial by Bavarian nationalists who had wanted to retain independence from the rest of Germany, as Austria had. As Bavaria had a majority-Catholic population, many people resented being ruled by the mostly Protestant northerners of Prussia. As a direct result of the Bavarian-Prussian feud, political parties formed to encourage Bavaria to break away and regain its independence.[18] Although the idea of Bavarian separatism was popular in the late 19th and early 20th century, apart from a small minority such as the Bavaria Party, most Bavarians accepted that Bavaria is part of Germany.

In the early 20th century, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Henrik Ibsen, and other artists were drawn to Bavaria, especially to the Schwabing district of Munich, a center of international artistic activity. This area was devastated by bombing and invasion during World War II.

Free State of Bavaria

Free State has been an adopted designation after the abolition of monarchy in the aftermath of World War I in several German states. On 12 November 1918, Ludwig III signed a document, the Anif declaration, releasing both civil and military officers from their oaths; the newly formed republican government, or "People's State" of Socialist premier Kurt Eisner,[19] interpreted this as an abdication. To date, however, no member of the House of Wittelsbach has ever formally declared renunciation of the throne.[20] On the other hand, none has ever since officially called upon their Bavarian or Stuart claims. Family members are active in cultural and social life, including the head of the house, Franz, Duke of Bavaria. They step back from any announcements on public affairs, showing approval or disapproval solely by Franz's presence or absence.

Eisner was assassinated in February 1919, ultimately leading to a Communist revolt and the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic being proclaimed 6 April 1919. After violent suppression by elements of the German Army and notably the Freikorps, the Bavarian Soviet Republic fell in May 1919. The Bamberg Constitution (Bamberger Verfassung) was enacted on 12 or 14 August 1919 and came into force on 15 September 1919 creating the Free State of Bavaria within the Weimar Republic. Extremist activity further increased, notably the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch led by the National Socialists, and Munich and Nuremberg became seen as Nazi strongholds under the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler. However, in the crucial German federal election, March 1933, the Nazis received less than 50% of the votes cast in Bavaria.

As a manufacturing centre, Munich was heavily bombed during World War II and was occupied by U.S. troops, becoming a major part of the American Zone of Allied-occupied Germany (1945–47) and then of "Bizonia".

The Rhenish Palatinate was detached from Bavaria in 1946 and made part of the new state Rhineland-Palatinate. During the Cold War, Bavaria was part of West Germany. In 1949, the Free State of Bavaria chose not to sign the Founding Treaty (Gründungsvertrag) for the formation of the Federal Republic of Germany, opposing the division of Germany into two states, after World War II. The Bavarian Parliament did not sign the Basic Law of Germany, mainly because it was seen as not granting sufficient powers to the individual Länder, but at the same time decided that it would still come into force in Bavaria if two-thirds of the other Länder ratified it. All of the other Länder ratified it, and so it became law.

Bavarian identity

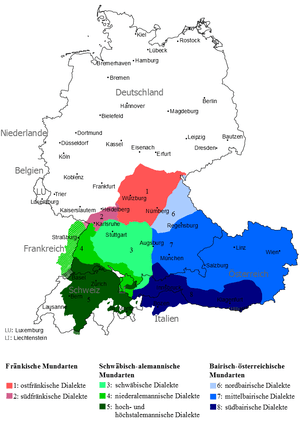

Bavarians have often emphasized a separate national identity and considered themselves as "Bavarians" first, "Germans" second.[21] This feeling started to come about more strongly among Bavarians when the Kingdom of Bavaria joined the Protestant Prussian-dominated German Empire while the Bavarian nationalists wanted to keep Bavaria as Catholic and an independent state. Nowadays, aside from the minority Bavaria Party, most Bavarians accept that Bavaria is part of Germany.[22] Another consideration is that Bavarians foster different cultural identities: Franconia in the north, speaking East Franconian German; Bavarian Swabia in the south west, speaking Swabian German; and Altbayern (so-called "Old Bavaria", the regions forming the "historic", pentagon-shaped Bavaria before the acquisitions through the Vienna Congress, at present the districts of the Upper Palatinate, Lower and Upper Bavaria) speaking Austro-Bavarian. In Munich, the Old Bavarian dialect was widely spread, but nowadays High German is predominantly spoken there. Moreover, by the expulsion of German speakers from Eastern Europe, Bavaria has received a large population that was not traditionally Bavarian. In particular, the Sudeten Germans, expelled from neighboring Czechoslovakia, have been deemed to have become the "fourth tribe" of Bavarians.

Flags and coat of arms

Flags

Uniquely among German states, Bavaria has two official flags of equal status, one with a white and blue stripe, the other with white and blue lozenges. Either may be used by civilians and government offices, who are free to choose between them.[23] Unofficial versions of the flag, especially a lozenge style with coat of arms, are sometimes used by civilians.

Coat of arms

The modern coat of arms of Bavaria was designed by Eduard Ege in 1946, following heraldic traditions.

- The Golden Lion: At the dexter chief, sable, a lion rampant Or, armed and langued gules. This represents the administrative region of Upper Palatinate.

- The "Franconian Rake": At the sinister chief, per fess dancetty, gules, and argent. This represents the administrative regions of Upper, Middle and Lower Franconia.

- The Blue "Pantier" (mythical creature from French heraldry, sporting a flame instead of a tongue): At the dexter base, argent, a Pantier rampant azure, armed Or and langued gules. This represents the regions of Lower and Upper Bavaria.

- The Three Lions: At the sinister base, Or, three lions passant guardant sable, armed and langued gules. This represents Swabia.

- The White-And-Blue inescutcheon: The inescutcheon of white and blue fusils askance was originally the coat of arms of the Counts of Bogen, adopted in 1247 by the House of Wittelsbach. The white-and-blue fusils are indisputably the emblem of Bavaria and these arms today symbolize Bavaria as a whole. Along with the People's Crown, it is officially used as the Minor Coat of Arms.

- The People's Crown (Volkskrone): The coat of arms is surmounted by a crown with a golden band inset with precious stones and decorated with five ornamental leaves. This crown first appeared in the coat of arms to symbolize sovereignty of the people after the royal crown was eschewed in 1923.

Geography

.jpg)

Bavaria shares international borders with Austria (Salzburg, Tyrol, Upper Austria and Vorarlberg) and Czechia (Karlovy Vary, Plzeň and South Bohemian Regions), as well as with Switzerland (across Lake Constance to the Canton of St. Gallen). Because all of these countries are part of the Schengen Area, the border is completely open. Neighboring states within Germany are Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, Thuringia, and Saxony. Two major rivers flow through the state: the Danube (Donau) and the Main. The Bavarian Alps define the border with Austria (including the Austrian federal-states of Vorarlberg, Tyrol and Salzburg), and within the range is the highest peak in Germany: the Zugspitze. The Bavarian Forest and the Bohemian Forest form the vast majority of the frontier with the Czechia and Bohemia.

The major cities in Bavaria are Munich (München), Nuremberg (Nürnberg), Augsburg, Regensburg, Würzburg, Ingolstadt, Fürth, and Erlangen.

The geographic center of the European Union is located in the northwestern corner of Bavaria.

Climate change and its effects

The effects of global warming are clearly visible in Bavaria as well.[24] The summer months are getting hotter.[24] For example, June 2019 was the warmest June in Bavaria since weather observations have been recorded[24] and the winter 2019/2020 was 3 degrees Celsius warmer than the average temperature for many years all over Bavaria. On 20 December 2019 a record temperature of 20.2 °C (68.4 °F) was recorded in Piding.[25] In general winter months are seeing more precipitation which is taking the form of rain more often than that of snow compared to the past.[24] Extreme weather like the 2013 European floods or the 2019 European heavy snowfalls is occurring more and more often. One effect of the continuing warming is the melting of almost all Bavarian Alpine glaciers: Of the five glaciers of Bavaria only the Höllentalferner is predicted to exist over a longer time perspective.The Südliche Schneeferner has almost vanished since the 1980s.[24]

Administrative divisions

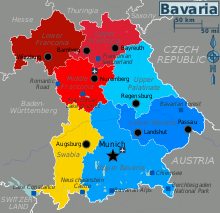

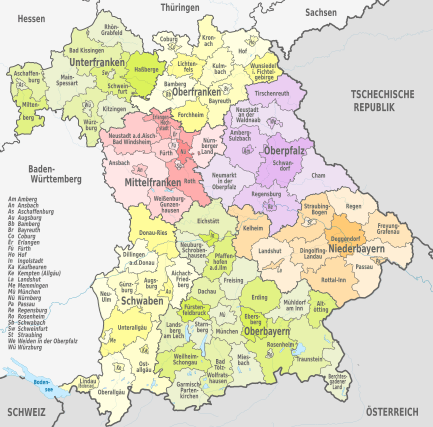

Bavaria is divided into seven administrative districts called Regierungsbezirke (singular Regierungsbezirk).

Administrative districts

- Upper Palatinate (German: Oberpfalz)

- Upper Bavaria (Oberbayern)

- Lower Bavaria (Niederbayern)

- Upper Franconia (Oberfranken)

- Middle Franconia (Mittelfranken)

- Lower Franconia (Unterfranken)

- Swabia (Schwaben)

Population and area

| Administrative region | Capital | Population (2011) | Area (km2) | No. municipalities | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Bavaria | Landshut | 1,192,641 | 9.48% | 10,330 | 14.6% | 258 | 12.5% |

| Lower Franconia | Würzburg | 1,315,882 | 10.46% | 8,531 | 12.1% | 308 | 15.0% |

| Upper Franconia | Bayreuth | 1,067,988 | 8.49% | 7,231 | 10.2% | 214 | 10.4% |

| Middle Franconia | Ansbach | 1,717,670 | 13.65% | 7,245 | 10.3% | 210 | 10.2% |

| Upper Palatinate | Regensburg | 1,081,800 | 8.60% | 9,691 | 13.7% | 226 | 11.0% |

| Swabia | Augsburg | 1,788,729 | 14.21% | 9,992 | 14.2% | 340 | 16.5% |

| Upper Bavaria | Munich | 4,418,828 | 35.12% | 17,530 | 24.8% | 500 | 24.3% |

| Total | 12,583,538 | 100.0% | 70,549 | 100.0% | 2,056 | 100.0% | |

Districts

Bezirke (districts) are the third communal layer in Bavaria; the others are the Landkreise and the Gemeinden or Städte. The Bezirke in Bavaria are territorially identical with the Regierungsbezirke, but they are self-governing regional corporation, having their own parliaments. In the other larger states of Germany, there are Regierungsbezirke which are only administrative divisions and not self-governing entities as the Bezirke in Bavaria.

Counties

The second communal layer is made up of 71 rural districts (called Landkreise, singular Landkreis) that are comparable to counties, as well as the 25 independent cities (Kreisfreie Städte, singular Kreisfreie Stadt), both of which share the same administrative responsibilities .

Rural districts:

Independent cities:

|

Municipalities

The 71 administrative districts are on the lowest level divided into 2,031 regular municipalities (called Gemeinden, singular Gemeinde). Together with the 25 independent cities (kreisfreie Städte, which are in effect municipalities independent of Landkreis administrations), there are a total of 2,056 municipalities in Bavaria.

In 44 of the 71 administrative districts, there are a total of 215 unincorporated areas (as of 1 January 2005, called gemeindefreie Gebiete, singular gemeindefreies Gebiet), not belonging to any municipality, all uninhabited, mostly forested areas, but also four lakes (Chiemsee-without islands, Starnberger See-without island Roseninsel, Ammersee, which are the three largest lakes of Bavaria, and Waginger See).

Major cities and towns

| City | Region | Inhabitants (2000) |

Inhabitants (2005) |

Inhabitants (2010) |

Inhabitants (2015) |

Change (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Munich | Upper Bavaria | 1,210,223 | 1,259,677 | 1,353,186 | 1,450,381 | +11.81 |

| Nuremberg | Middle Franconia | 488,400 | 499,237 | 505,664 | 509,975 | +3.53 |

| Augsburg | Swabia | 254,982 | 262,676 | 264,708 | 286,374 | +3.81 |

| Regensburg | Upper Palatinate | 125,676 | 129,859 | 135,520 | 145,465 | +7.83 |

| Ingolstadt | Upper Bavaria | 115,722 | 121,314 | 125,088 | 132,438 | +8.09 |

| Würzburg | Lower Franconia | 127,966 | 133,906 | 133,799 | 124,873 | +4.56 |

| Fürth | Middle Franconia | 110,477 | 113,422 | 114,628 | 124,171 | +3.76 |

| Erlangen | Middle Franconia | 100,778 | 103,197 | 105,629 | 108,336 | +4.81 |

| Bayreuth | Upper Franconia | 74,153 | 73,997 | 72,683 | 72,148 | −1.98 |

| Bamberg | Upper Franconia | 69,036 | 70,081 | 70,004 | 73,331 | +1.40 |

| Aschaffenburg | Lower Franconia | 67,592 | 68,642 | 68,678 | 68,986 | +1.61 |

| Landshut | Lower Bavaria | 58,746 | 61,368 | 63,258 | 69,211 | +7.68 |

| Kempten | Swabia | 61,389 | 61,360 | 62,060 | 66,947 | +1.09 |

| Rosenheim | Upper Bavaria | 58,908 | 60,226 | 61,299 | 61,844 | +4.06 |

| Neu-Ulm | Swabia | 50,188 | 51,410 | 53,504 | 57,237 | +6.61 |

| Schweinfurt | Lower Franconia | 54,325 | 54,273 | 53,415 | 51,969 | −1.68 |

| Passau | Lower Bavaria | 50,536 | 50,651 | 50,594 | 50,566 | +0.11 |

| Freising | Upper Bavaria | 40,890 | 42,854 | 45,223 | 46,963 | +10.60 |

| Straubing | Lower Bavaria | 44,014 | 44,633 | 44,450 | 46,806 | +0.99 |

| Dachau | Upper Bavaria | 38,398 | 39,922 | 42,954 | 46,705 | +11.87 |

Source: Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung[26][27]

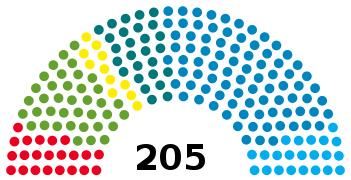

Politics

Bavaria has a multiparty system dominated by the conservative Christian Social Union (CSU), which has won every election since 1945, The Greens, which became the second biggest political party in the 2018 parliament elections and the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), which dominates in Munich. Thus far Wilhelm Hoegner has been the only SPD candidate to ever become Minister-President; notable successors in office include multi-term Federal Minister Franz Josef Strauss, a key figure among West German conservatives during the Cold War years, and Edmund Stoiber, who both failed with their bids for Chancellorship. The German Greens and the center-right Free Voters have been represented in the state parliament since 1986 and 2008 respectively.

In the 2003 elections the CSU won a ⅔ supermajority – something no party had ever achieved in postwar Germany. However, in the subsequent 2008 elections the CSU lost the absolute majority for the first time in 46 years.[28] The losses were partly attributed by some to the CSU's stance for an anti-smoking bill. (A first anti-smoking law had been proposed by the CSU and passed but was watered down after the election, after which a referendum enforced a strict antismoking bill with a large majority).

Current Landtag

The last state elections were held on 14 October 2018 in which the CSU lost its absolute majority in the state parliament in part due to the party's stances as part of the federal government, winning 37.2% of the vote; the party's second worst election outcome in its history. The Greens who had surged in the polls leading up to the election have replaced the social-democratic SPD as the second biggest force in the Landtag with 17.5% of the vote. The SPD lost over half of its previous share compared to 2013 with a mere 9.7% in 2018. The liberals of the FDP were again able to reach the five-percent-threshold in order to receive mandates in parliament after they were not part of the Landtag after the 2013 elections. Also entering the new parliament will be the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) with 10.2% of the vote.[29] The center-right Free Voters party gained 11.6% of the vote and formed a government coalition with the CSU which lead to the subsequent reelection of Markus Söder as Minister-President of Bavaria.

Government

The Constitution of Bavaria of the Free State of Bavaria was enacted on 8 December 1946. The new Bavarian Constitution became the basis for the Bavarian State after the Second World War.

Bavaria has a unicameral Landtag (English: State Parliament), elected by universal suffrage. Until December 1999, there was also a Senat, or Senate, whose members were chosen by social and economic groups in Bavaria, but following a referendum in 1998, this institution was abolished.

The Bavarian State Government consists of the Minister-President of Bavaria, eleven Ministers and six Secretaries of State. The Minister-President is elected for a period of five years by the State Parliament and is head of state. With the approval of the State Parliament he appoints the members of the State Government. The State Government is composed of the:

- Ministry of the Interior, Building and Transport (Staatsministerium des Innern, für Bau und Verkehr)

- Ministry of Education and Culture, Science and Art (Staatsministerium für Bildung und Kultus, Wissenschaft und Kunst)

- Ministry of Finance, for Rural Development and Homeland (Staatsministerium der Finanzen, für Landesentwicklung und Heimat)

- Ministry of Economic Affairs and Media, Energy and Technology (Staatsministerium für Wirtschaft und Medien, Energie und Technologie)

- Ministry of Environment and Consumer Protection (Staatsministerium für Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz)

- Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, Family and Integration (Staatsministerium für Arbeit und Soziales, Familie und Integration)

- Ministry of Justice (Staatsministerium der Justiz)

- Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Forestry (Staatsministerium für Ernährung, Landwirtschaft und Forsten)

- Ministry of Public Health and Care Services (Staatsministerium für Gesundheit und Pflege)

Political processes also take place in the seven regions (Regierungsbezirke or Bezirke) in Bavaria, in the 71 administrative districts (Landkreise) and the 25 towns and cities forming their own districts (kreisfreie Städte), and in the 2,031 local authorities (Gemeinden).

In 1995 Bavaria introduced direct democracy on the local level in a referendum. This was initiated bottom-up by an association called Mehr Demokratie (English: More Democracy). This is a grass-roots organization which campaigns for the right to citizen-initiated referendums. In 1997 the Bavarian Supreme Court tightened the regulations considerably (including by introducing a turn-out quorum). Nevertheless, Bavaria has the most advanced regulations on local direct democracy in Germany. This has led to a spirited citizens' participation in communal and municipal affairs—835 referenda took place from 1995 through 2005.

Minister-presidents of Bavaria since 1945

| Ministers-President of Bavaria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | Born and died | Party affiliation | Begin of tenure | End of tenure |

| 1 | Fritz Schäffer | 1888–1967 | CSU | 1945 | 1945 |

| 2 | Wilhelm Hoegner | 1887–1980 | SPD | 1945 | 1946 |

| 3 | Hans Ehard | 1887–1980 | CSU | 1946 | 1954 |

| 4 | Wilhelm Hoegner | 1887–1980 | SPD | 1954 | 1957 |

| 5 | Hanns Seidel | 1901–1961 | CSU | 1957 | 1960 |

| 6 | Hans Ehard | 1887–1980 | CSU | 1960 | 1962 |

| 7 | Alfons Goppel | 1905–1991 | CSU | 1962 | 1978 |

| 8 | Franz Josef Strauß | 1915–1988 | CSU | 1978 | 1988 |

| 9 | Max Streibl | 1932–1998 | CSU | 1988 | 1993 |

| 10 | Edmund Stoiber | *1941 | CSU | 1993 | 2007 |

| 11 | Günther Beckstein | *1943 | CSU | 2007 | 2008 |

| 12 | Horst Seehofer | *1949 | CSU | 2008 | 2018 |

| 13 | Markus Söder | *1967 | CSU | 2018 | Incumbent |

Designation as a "free state"

Unlike most German states (Länder), which simply designate themselves as "State of" (Land [...]), Bavaria uses the style of "Free State of Bavaria" (Freistaat Bayern). The difference from other states is purely terminological, as German constitutional law does not draw a distinction between "States" and "Free States". The situation is thus analogous to the United States, where some states use the style "Commonwealth" rather than "State". The choice of "Free State", a creation of the early 20th century and intended to be a German alternative to (or translation of) the Latin-derived republic, has historical reasons, Bavaria having been styled that way even before the current 1946 Constitution was enacted (in 1918 after the de facto abdication of Ludwig III). Two other states, Saxony and Thuringia, also use the style "Free State"; unlike Bavaria, however, these were not part of the original states when the Grundgesetz was enacted but joined the federation later on, in 1990, as a result of German reunification. Saxony had used the designation as "Free State" from 1918 to 1952.

Arbitrary arrest and human rights

In July 2017, Bavaria's parliament enacted a new revision of the "Gefährdergesetz", allowing the authorities to imprison a person for a three months term, renewable indefinitely, when s/he hasn't committed a crime but it is assumed that s/he might commit a crime "in the near future".[30] Critics like the prominent journalist Heribert Prantl have called the law "shameful" and compared it to Guantanamo Bay detention camp,[31] assessed it to be in violation of the European Convention on Human Rights,[32] and also compared it to the legal situation in Russia, where a similar law allows for imprisonment for a maximum term of two years (i.e., not indefinitely)[33]

Economy

Bavaria has long had one of the largest economies of any region in Germany, and in Europe.[34] Its GDP in 2007 exceeded €434 billion (about U.S. $600 billion).[35] This makes Bavaria itself one of the largest economies in Europe, and only 20 countries in the world have a higher GDP.[36] The Gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 617.1 billion € in 2018, accounting for 18.5% of German economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was 43,500 € or 144% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 114% of the EU average. This makes Bavaria one of the wealthiest regions in Europe.[37] Bavaria has strong economic ties with Austria, the Czech Republic, Switzerland, and Northern Italy.[38]

Companies

Many large companies are headquartered in Bavaria, including Adidas, Allianz, Audi, BMW, Brose, BSH Hausgeräte, HypoVereinsbank, Infineon, KUKA, MAN SE, MTU Aero Engines, Munich Re, Osram, Puma, Rohde & Schwarz, Schaeffler, Siemens, Wacker Chemie and Wirecard.

Tourism

With 40 million tourists in 2019, Bavaria is the most visited German state and one of Europe's leading tourist destinations.[39]

Unemployment

The unemployment rate stood at 2.6% in October 2018, the lowest in Germany and one of the lowest in the European Union.[40]

| Year[41] | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 5.5 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.8 | 6.8 | 5.3 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 2.9 |

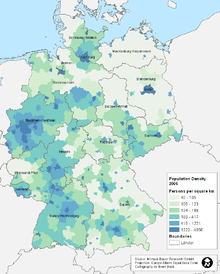

Demographics

Bavaria has a population of approximately 12.9 million inhabitants (2016). 8 of the 80 largest cities in Germany are located within Bavaria with Munich being the largest (1,450,381 inhabitants, approximately 5.7 million when including the broader metropolitan area), followed by Nuremberg (509,975 inhabitants, approximately 3.6 million when including the broader metropolitan area) and Augsburg (286,374 inhabitants). All other cities in Bavaria had less than 150,000 inhabitants each in 2015. Population density in Bavaria was 182 inhabitants per square kilometre (470/sq mi), below the national average of 227 inhabitants per square kilometre (590/sq mi). Foreign nationals resident in Bavaria (both immigrants and refugees/asylum seekers) were principally from other EU countries and Turkey.

| Top-ten foreign resident populations[42] | ||

| Nationality | Population (31.12.2019) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 192,235 | |

| 2 | 180,455 | |

| 3 | 119,880 | |

| 4 | 116,145 | |

| 5 | 104,680 | |

| 6 | 84,570 | |

| 7 | 75,970 | |

| 8 | 75,945 | |

| 9 | 75,900 | |

| 10 | 56,645 | |

Vital statistics

- Births January–November 2016 =

- Births January–November 2017 =

- Deaths January–November 2016 =

- Deaths January–November 2017 =

- Natural growth January–November 2016 =

- Natural growth January–November 2017 =

Culture

Some features of the Bavarian culture and mentality are remarkably distinct from the rest of Germany. Noteworthy differences (especially in rural areas, less significant in the major cities) can be found with respect to religion, traditions, and language.

Religion

Bavarian culture (Altbayern) has a long and predominant tradition of Catholic faith. Pope emeritus Benedict XVI (Joseph Alois Ratzinger) was born in Marktl am Inn in Upper Bavaria and was Cardinal-Archbishop of Munich and Freising. Otherwise, the culturally Franconian and Swabian regions of the modern State of Bavaria are historically more diverse in religiosity, with both Catholic and Protestant traditions. In 1925, 70.0% of the Bavarian population was Catholic, 28.8% was Protestant, 0.7% was Jewish, and 0.5% was placed in other religious categories.[44]

As of 2018 48.8% of Bavarians adhered to Catholicism (a decline from 70.4% in 1970).[45][46] 17.9% of the population adheres to the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, which has also declined since 1970.[45][46] 3% was Orthodox, Muslims make up 4.0% of the population of Bavaria. 28.1% of Bavarians are irreligious or adhere to other religions.

Traditions

Bavarians commonly emphasize pride in their traditions. Traditional costumes collectively known as Tracht are worn on special occasions and include in Altbayern Lederhosen for males and Dirndl for females. Centuries-old folk music is performed. The Maibaum, or Maypole (which in the Middle Ages served as the community's business directory, as figures on the pole represented the trades of the village), and the bagpipes of the Upper Palatinate region bear witness to the ancient Celtic and Germanic remnants of cultural heritage of the region. There are many traditional Bavarian sports disciplines, e.g. the Aperschnalzen, competitive whipcracking.

Whether actually in Bavaria, overseas or with citizens from other nations Bavarians continue to cultivate their traditions. They hold festivals and dances to keep their heritage alive. In New York City the German American Cultural Society is a larger umbrella group for others which represent a specific part of Germany, including the Bavarian organizations. They present a German parade called Steuben Parade each year. Various affiliated events take place amongst its groups, one of which is the Bavarian Dancers.

Food and drink

Bavarians tend to place a great value on food and drink. In addition to their renowned dishes, Bavarians also consume many items of food and drink which are unusual elsewhere in Germany; for example Weißwurst ("white sausage") or in some instances a variety of entrails. At folk festivals and in many beer gardens, beer is traditionally served by the litre (in a Maß). Bavarians are particularly proud of the traditional Reinheitsgebot, or beer purity law, initially established by the Duke of Bavaria for the City of Munich (i.e. the court) in 1487 and the duchy in 1516. According to this law, only three ingredients were allowed in beer: water, barley, and hops. In 1906 the Reinheitsgebot made its way to all-German law, and remained a law in Germany until the EU partly struck it down in 1987 as incompatible with the European common market.[47] German breweries, however, cling to the principle, and Bavarian breweries still comply with it in order to distinguish their beer brands.[48] Bavarians are also known as some of the world's most beer-loving people with an average annual consumption of 170 liters per person, although figures have been declining in recent years.

Bavaria is also home to the Franconia wine region, which is situated along the Main River in Franconia. The region has produced wine (Frankenwein) for over 1,000 years and is famous for its use of the Bocksbeutel wine bottle. The production of wine forms an integral part of the regional culture, and many of its villages and cities hold their own wine festivals (Weinfeste) throughout the year.

Language and dialects

Three German dialects are most commonly spoken in Bavaria: Austro-Bavarian in Old Bavaria (Upper Bavaria, Lower Bavaria and the Upper Palatinate), Swabian German (an Alemannic German dialect) in the Bavarian part of Swabia (south west) and East Franconian German in Franconia (North). In the small town Ludwigsstadt in the north, district Kronach in Upper Franconia, Thuringian dialect is spoken. During the 20th century an increasing part of the population began to speak Standard German (Hochdeutsch), mainly in the cities.

Ethnography

Bavarians consider themselves to be egalitarian and informal. Their sociability can be experienced at the annual Oktoberfest, the world's largest beer festival, which welcomes around six million visitors every year, or in the famous beer gardens. In traditional Bavarian beer gardens, patrons may bring their own food but buy beer only from the brewery that runs the beer garden.[49]

In the United States, particularly among German Americans, Bavarian culture is viewed somewhat nostalgically, and several "Bavarian villages" have been founded, most notably Frankenmuth, Michigan; Helen, Georgia; and Leavenworth, Washington. Since 1962, the latter has been styled with a Bavarian theme and is home to an Oktoberfest celebration it claims is among the most attended in the world outside of Munich.[50]

Xenophobia

Xenophobic and anti-Semitic attitudes are widespread in Bavaria,[51][52] according to the "Mitte" study of 2015 by Leipzig University, with 33.1% of Bavarians agreeing with xenophobic statements. This is the highest approval rate among West German federal states (average: 20%) and the second highest nationwide (national average: 24.3%). In addition, Bavaria has with 12.6% the highest approval for anti-Semitic statements of all federal states (national average: 8.4%).

Sports

Football

Bavaria is home to several football clubs including FC Bayern Munich, 1. FC Nürnberg, FC Augsburg, TSV 1860 Munich, FC Ingolstadt 04 and SpVgg Greuther Fürth. Bayern Munich is the most successful football team in Germany having won a record 30 German titles and 5 UEFA Champions League titles. They are followed by 1. FC Nürnberg who have won 9 titles. SpVgg Greuther Fürth have won 3 championships while TSV 1860 Munich have been champions once.

Ice hockey

There are five Bavarian ice hockey teams playing in the German top-tier league DEL: EHC Red Bull München, Nürnberg Ice Tigers, Augsburger Panther, ERC Ingolstadt, and Straubing Tigers.

Bavarians

Many famous people have been born or lived in present-day Bavaria:

- Kings: Arnulf of Carinthia, Carloman of Bavaria, Charles the Fat, Lothair I, Louis the Child, Louis the German, Louis the Younger, Ludwig I of Bavaria, Ludwig II of Bavaria, Ludwig III of Bavaria, Maximilian I Joseph of Bavaria, Maximilian II of Bavaria, Otto of Bavaria

- Religious leaders: Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger); Pope Damasus II, Pope Victor II.

- Painters: Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Altdorfer, Carl Spitzweg, Erwin Eisch, Franz von Lenbach, Franz von Stuck, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Hans Holbein the Elder, Johann Christian Reinhart, Lucas Cranach, Paul Klee.

- Classical musicians Orlando di Lasso, Christoph Willibald Gluck, Leopold Mozart, Max Reger, Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, Carl Orff, Johann Pachelbel, Theobald Boehm, Klaus Nomi.

- Other musicians Hans-Jürgen Buchner, Barbara Dennerlein, Klaus Doldinger, Bands: Spider Murphy Gang, Sportfreunde Stiller, Obscura, Michael Bredl

- Opera singers Jonas Kaufmann, Diana Damrau.

- Writers, poets and playwrights Hans Sachs, Jean Paul, Friedrich Rückert, August von Platen-Hallermünde, Frank Wedekind, Christian Morgenstern, Oskar Maria Graf, Bertolt Brecht, Lion Feuchtwanger, Thomas Mann, Klaus Mann, Golo Mann, Ludwig Thoma, Michael Ende, Ludwig Aurbacher.

- Scientists Max Planck, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, Werner Heisenberg, Adam Ries, Joseph von Fraunhofer, Georg Ohm, Johannes Stark, Carl von Linde, Ludwig Prandtl, Rudolf Mössbauer, Lothar Rohde, Hermann Schwarz, Robert Huber, Martin Behaim, Levi Strauss, Rudolf Diesel.

- Physicians Alois Alzheimer, Georg Simon Ohm, Max Joseph von Pettenkofer, Sebastian Kneipp.

- Politicians Ludwig Erhard, Horst Seehofer, Christian Ude, Kurt Eisner, Franz-Josef Strauß, Roman Herzog, Leonard John Rose, Henry Kissinger.

- Football players Max Morlock, Karl Mai, Franz Beckenbauer, Sepp Maier, Gerd Müller, Paul Breitner, Bernd Schuster, Klaus Augenthaler, Lothar Matthäus, Philipp Lahm, Bastian Schweinsteiger, Holger Badstuber, Thomas Müller, Mario Götze, Dietmar Hamann, Stefan Reuter

- Other sportspeople Bernhard Langer, Dirk Nowitzki

- Actors Michael Herbig, Werner Stocker, Helmut Fischer, Walter Sedlmayr, Gustl Bayrhammer, Ottfried Fischer, Ruth Drexel, Elmar Wepper, Fritz Wepper, Uschi Glas, Yank Azman.

- Entertainers Siegfried Fischbacher

- Film directors Helmut Dietl, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Bernd Eichinger, Joseph Vilsmaier, Hans Steinhoff, Heinz Badewitz and Werner Herzog.

- Designers Peter Schreyer, Damir Doma

- Entrepreneurs Charles Diebold, Levi Strauss

- Military Claus von Stauffenberg

- Nazis: Sepp Dietrich, Karl Fiehler, Karl Gebhardt, Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Alfred Jodl, Josef Kollmer, Joseph Mengele, Ernst Röhm, Franz Ritter von Epp, Julius Streicher

- Others: Kaspar Hauser, The Smith of Kochel, Mathias Kneißl, Matthias Klostermayr

See also

- Outline of Germany

- Former countries in Europe after 1815

- List of Bavaria-related topics

- List of Premiers of Bavaria

- List of rulers of Bavaria

References

- "Bevölkerung: Gemeinden, Geschlecht, Quartale, Jahr". Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik und Datenverarbeitung (in German). July 2019.

- "GDP NRW official statistics". Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Planet, Lonely. "Bavaria – Lonely Planet". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Unknown, Unknown. "Bavaria". Britannica. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen Stand 31.12 2016" (PDF). ekd.de. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Local, The. "Bavaria – The Local". The Local. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Campbell, Eric. "Germany – A Bavarian Fairy Tale". ABC. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Bayern: Amtliche Statistik

- Dovid Solomon Ganz, Tzemach Dovid (3rd edition), part 2, Warsaw 1878, pp. 71, 85 (available online Archived 14 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine )

- Brown, Warren (2001). Unjust Seizure (1st ed.). p. 63. ISBN 9780801437908. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Unknown, Unknown. "History of Bavaria". Guide to Bavaria. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Frassetto, Michael (2013). The Early Medieval World: From the Fall of Rome to the Time of Charlemagne [2 Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 145. ISBN 978-1598849967.

- Collins, Roger (2010). Early Medieval Europe, 300–1000. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 273. ISBN 978-1137014283.

- Harrington, Joel F. (1995). Reordering Marriage and Society in Reformation Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0521464833.

- Hanson, Paul R. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0810878921.

bavaria kingdom 1806 napoleon.

- Sheehan, James J. (1993). German History, 1770–1866. Clarendon Press. p. 265. ISBN 978-0198204329.

- James Minahan (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 106–. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany, New York, NY, Simon & Schuster, 2011, p. 33

- Karacs, Imre (13 July 1996). "Bavaria buries the royal dream Funeral of Prince Albrechty". The Independent.

- Bavaria Guide Archived 4 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. European-vacation-planner.com. Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- Lunau, Kate. (25 June 2009) "No more Bavarian separatism – World" Archived 10 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Macleans.ca, 25 June 2009, Retrieved on 2013-07-16.

- "Flag Legislation (Bavaria, Germany), Executive Order on Flags of 1954". Flags of the World. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- https://www.sueddeutsche.de/bayern/bayern-klimawandel-umwelt-vorhersagen-1.4539824

- Bayerischer Rundfunk (3 March 2020), Klimawandel in Bayern: Längst bei uns angekommen (in German), retrieved 22 April 2020

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, München 2015 (30 August 2015). "Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik – GENESIS-Online Bayern". bayern.de.

- Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik, München 2017 (23 April 2017). "Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik – GENESIS-Online Bayern". bayern.de.

- n-tv:Fiasko für die CSU Archived 29 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- tagesschau.de. "tagesschau.de". wahl.tagesschau.de. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Gefährder-Gesetz verschärft, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 19 July 2017

- Bayern führt Unendlichkeitshaft ein, Heribert Prantl, 20 July 2017

- Reisewarnung für Bayern, Udo Vetter, 20 July 2017

- Erinnert ihr euch noch daran, als Bayern als Rechtsstaat galt?, Felix von Leitner, 20 July 2017

- Its GDP is 143% of the EU average (as of 2005) whilst the German average is 121.5%. Source: Eurostat

- Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg. "Gemeinsames Datenangebot der Statistischen Ämter des Bundes und der Länder". baden-wuerttemberg.de.

- See the list of countries by GDP.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- https://www.business-transfer.eu/support_points/germany/

- "Daten & Fakten". Bavarian Ministry of Economic Affairs, Regional Development and Energy (in German). Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Arbeitslosenquote nach Bundesländern in Deutschland 2018 | Statista". Statista (in German). Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- (Destatis) Statistisches Bundesamt (13 November 2018). "Federal Statistical Office Germany – GENESIS-Online". www-genesis.destatis.de. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- German Statistical Office

- "Statistik Portal". Statische Ämter. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Grundriss der Statistik. II. Gesellschaftsstatistik by Wilhelm Winkler, p. 36

- Bayerischer Rundfunk. "Massive Kirchenaustritte: Das Ende der Kirche wie wir sie kennen – Religion – Themen – BR.de". br.de. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015.

- "Kirchenmitgliederzahlen Stand 31.12.2018" (PDF). ekd.de. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- "30.04.2005 – EU-Recht". 30 April 2005. Archived from the original on 30 April 2005.

- Bayerischer Rundfunk. "To Bier or not to Bier? vom 22.10.2015: Das Reinheitsgebot und seine Tücken – BR Mediathek VIDEO". br.de. Archived from the original on 27 October 2015.

- Königlicher Hirschgarten. "Ein paar Worte zu unserem Biergarten in München ... (in German)".

- "Leavenworth Washington Hotels, Lodging, Festivals & Events". Visit Leavenworth Washington, USA. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- Kanning, Sarah. "Studie: Alltägliche Ausländerfeindlichkeit in Bayern". Süddeutsche.de (in German). Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- WELT (7 April 2015). "Studie: Bayern zweitstärkstes Land bei Fremdenfeindlichkeit". Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). 1911.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bavaria. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Bavaria. |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.jpg)

-en.png)