Leopold II of Belgium

Leopold II (Dutch: Leopold Lodewijk Filips Maria Victor; French: Léopold Louis Philippe Marie Victor; German: Leopold Ludwig Philipp Maria Viktor; 9 April 1835 – 17 December 1909) was King of the Belgians from 1865 to 1909 and, in a completely separate role, the Sovereign of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908. During his absolute rule of the Congo, an estimated 2-10 million Africans died[1][2][3] and conditions there led to an early use of the term "crime against humanity."[4]

| Leopold II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| King of the Belgians | |||||

| Reign | 17 December 1865 – 17 December 1909 | ||||

| Predecessor | Leopold I | ||||

| Successor | Albert I | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Sovereign of the Congo Free State | |||||

| Reign | 1 July 1885 – 15 November 1908 | ||||

| Governors-general | |||||

| Born | 9 April 1835 Brussels, Belgium | ||||

| Died | 17 December 1909 (aged 74) Laeken, Brussels, Belgium | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue (among other) |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Father | Leopold I of Belgium | ||||

| Mother | Louise of Orléans | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Born in Brussels as the second but eldest surviving son of Leopold I and Louise of Orléans, he succeeded his father to the Belgian throne in 1865 and reigned for 44 years until his death – the longest reign of any Belgian monarch. He died without surviving legitimate sons. The current Belgian king descends from his nephew and successor, Albert I.

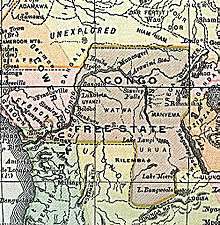

Leopold was the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, a private project undertaken on his own behalf. He used Henry Morton Stanley to help him lay claim to the Congo, the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the colonial nations of Europe authorized his claim by committing the Congo Free State to improving the lives of the native inhabitants. Leopold ignored these conditions and ran the Congo using the mercenary Force Publique for his personal gain. He extracted a fortune from the territory, initially by the collection of ivory, and after a rise in the price of rubber in the 1890s, by forced labour from the native population to harvest and process rubber.

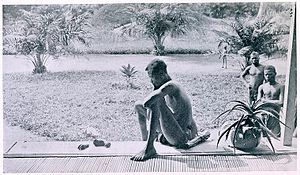

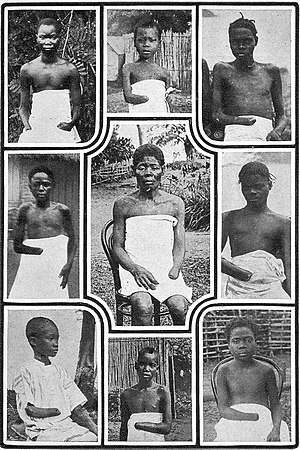

Leopold's administration of the Congo was characterised by murder, torture, and atrocities, resulting from notorious systematic brutality. The hands of men, women, and children were amputated when the quota of rubber was not met. These and other facts were established at the time by eyewitness testimony and on-site inspection by an international Commission of Inquiry (1904). Millions of the Congolese people died: modern estimates range from 1 million to 15 million deaths, with a consensus growing around 10 million. Some historians argue against this figure, citing the absence of reliable censuses, the enormous mortality of diseases such as smallpox or sleeping sickness, and the fact that there were only 175 administrative agents in charge of rubber exploitation.[5][6] In 1908, the reports of deaths and abuse induced the Belgian government to take over the administration of the Congo from Leopold.

Early life

Leopold was born in Brussels on 9 April 1835, the second child of the reigning Belgian monarch, Leopold I, and of his second wife, Louise, the daughter of King Louis Philippe of France. The French Revolution of 1848 forced Louis Philippe to flee to the United Kingdom. The British monarch, Queen Victoria, was Leopold II's first cousin, as Leopold's father and Victoria's mother were siblings. Louis Philippe died two years later, in 1850. Leopold's fragile mother was deeply affected by the death of her father, and her health deteriorated. She died of tuberculosis that same year, when Leopold was 15 years old.

Marriage and family

On 22 August 1853, at the age of 18, he married Marie Henriette of Austria in Brussels. Marie Henriette was a cousin of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria and granddaughter of Emperor Leopold II. Marie Henriette was lively and energetic, and endeared herself to the people by her character and benevolence, and her beauty gained for her the sobriquet of "The Rose of Brabant". She was also an accomplished artist and musician.[7] She was passionate about horseback riding to the point that she would care for her horses personally. Some joked about this "marriage of a stableman and a nun",[8] the shy and withdrawn Leopold referred to as the nun.

Four children were born of this marriage, three daughters and one son, also named Leopold. The younger Leopold died in 1869 at the age of nine from pneumonia after falling into a pond. His death was a source of great sorrow for King Leopold. The marriage became unhappy, and the couple separated completely after a last attempt to have another son, a union that resulted in the birth of their last daughter Clementine. Marie Henriette retreated to Spa in 1895, and died there in 1902.[9]

The Abbot: Oh! Sire, at your age?

The King: You should try it for yourself!

Leopold had many mistresses. In 1899, in his sixty-fifth year, Leopold took as a mistress Caroline Lacroix, a sixteen-year-old French prostitute, and they remained together for the next decade until his death. Leopold lavished upon her large sums of money, estates, gifts, and a noble title, Baroness Vaughan. Owing to these gifts and the unofficial nature of their relationship, Caroline was deeply unpopular among the Belgian people and internationally. She and Leopold married secretly in a religious ceremony five days before his death. Their failure to perform a civil ceremony rendered the marriage invalid under Belgian law. After the king's death, it was soon discovered that he had left Caroline a large fortune, which the Belgian government and Leopold's three estranged daughters tried to seize as rightfully theirs. Caroline bore two sons who were probably Leopold's.

Early political career

%3B_kroonprins_en_hertog_van_Brabant%2C_later_koning_Leopold_II_der_Belgen%2C_Granzella%2C_Felixarchief%2C_12_12732.jpg)

As Leopold's older brother, also named Louis Philippe, had died the year before Leopold's birth, Leopold was heir to the throne from his birth. When he was 9 years old, Leopold received the title of Duke of Brabant, and was appointed a sub-lieutenant in the army. He served in the army until his accession in 1865, by which time he had reached the rank of lieutenant-general.[7]

Leopold's public career began on his attaining the age of majority in 1855, when he became a member of the Belgian Senate. He took an active interest in the senate, especially in matters concerning the development of Belgium and its trade,[7] and began to urge Belgium's acquisition of colonies. Leopold traveled extensively abroad from 1854 to 1865, visiting India, China, Egypt, and the countries on the Mediterranean coast of Africa. His father died on December 10, 1865, and Leopold took the oath of office on December 17, in his thirtieth year.[9]

Domestic reign

Leopold became king in 1865. He explained his goal for his reign in an 1888 letter addressed to his brother, Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders: "the country must be strong, prosperous, therefore have colonies of her own, beautiful and calm."[10]

Leopold's reign was marked by a number of major political developments. The Liberals governed Belgium from 1857 to 1880, and during its final year in power legislated the Frère-Orban Law of 1879. This law created free, secular, compulsory primary schools supported by the state and withdrew all state support from Roman Catholic primary schools. The Catholic Party obtained a parliamentary majority in 1880, and four years later restored state support to Catholic schools. In 1885, various socialist and social democratic groups drew together and formed the Labour Party. Increasing social unrest and the rise of the Labour Party forced the adoption of universal male suffrage in 1893.

During Leopold's reign other social changes were enacted into law. Among these were the right of workers to form labour unions and the abolition of the livret d'ouvrier, an employment record book. Laws against child labour were passed. Children younger than 12 were not allowed to work in factories, children younger than 16 were not allowed to work at night, and women younger than 21 years old were not allowed to work underground. Workers gained the right to be compensated for workplace accidents and were given Sundays off.

The first revision of the Belgian constitution came in 1893. Universal male suffrage was introduced, though the effect of this was tempered by plural voting. The eligibility requirements for the senate were reduced, and elections would be based on a system of proportional representation, which continues to this day. Leopold pushed strongly to pass a royal referendum, whereby the king would have the power to consult the electorate directly on an issue, and use his veto according to the results of the referendum. The proposal was rejected, as it would have given the king the power to override the elected government. Leopold was so disappointed that he considered abdication.[11]

Leopold emphasized military defence as the basis of neutrality, and strove to make Belgium less vulnerable militarily. He achieved the construction of defensive fortresses at Liège, at Namur and at Antwerp. During the Franco-Prussian War, he managed to preserve Belgium's neutrality in a period of unusual difficulty and danger.[7] Leopold pushed for a reform in military service, but he was unable to obtain one until he was on his deathbed. Under the old system of Remplacement, the Belgian army was a combination of volunteers and a lottery, and it was possible for men to pay for substitutes for service. This was replaced by a system in which one son in every family would have to serve in the military.

Builder King

Leopold commissioned a great number of buildings, urban projects and public works, largely with the profits generated from exploitation of natural resources and the population of the Congo. These projects earned him the epithet of "Builder King" (Koning-Bouwheer in Dutch, le Roi-Bâtisseur in French). The public buildings were mainly in Brussels, Ostend and Antwerp, and include the Hippodrome Wellington racetrack, the Royal Galleries and Maria Hendrikapark in Ostend; the Royal Museum for Central Africa and its surrounding park in Tervuren; the Cinquantenaire park, triumphal arch and complex, and the Duden Park in Brussels, and the 1895-1905 Antwerpen-Centraal railway station. The majority of the required funds for these projects originated from the brutal exploitation of the Congo Free State.

In addition to his public works, he acquired and built numerous private properties for himself inside and outside Belgium. He expanded the grounds of the Royal Castle of Laeken, and built the Royal Greenhouses, the Japanese Tower and the Chinese Pavilion near the palace. In the Ardennes, his domains consisted of 6,700 hectares (17,000 acres) of forests and agricultural lands and the châteaux of Ardenne, Ciergnon, Fenffe, Villers-sur-Lesse and Ferage. He also built important country estates on the French Riviera, including the Villa des Cèdres and its botanical garden, and the Villa Leopolda.

Thinking of the future after his death, Leopold did not want the collection of estates, lands and heritage buildings he had privately amassed to be scattered among his daughters, each of whom was married to a foreign prince. In 1900, he created the Royal Trust, by means of which he donated most of his property to the Belgian nation. This preserved them to beautify Belgium in perpetuity, while still allowing future generations of the Belgian royal family the privilege of their use.

Attempted assassination

On 15 November 1902, Italian anarchist Gennaro Rubino attempted to assassinate Leopold, who was riding in a royal cortege from a ceremony at Saint-Gudule Cathedral in memory of his recently deceased wife, Marie Henriette. After Leopold's carriage passed, Rubino fired three shots at the procession. The shots missed Leopold but almost killed the king's Grand Marshall, Count Charles John d'Oultremont. Rubino was immediately arrested and subsequently sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison in 1918.

The king replied after the attack to a senator: "My dear senator, if fate wants me shot, too bad!" ("Mon cher Sénateur, si la fatalité veut que je sois atteint, tant pis"!)[12] After the failed regicide the security of the king was questioned, because the glass of the landaus was 2 cm thick. Elsewhere in Europe, the news of this assassination attempt was received with alarm. Heads of state and the pope sent telegrams to the king congratulating him for surviving the assassination attempt. Many people remembered the earlier assassinations of Empress Elisabeth of Austria and King Umberto I of Italy by other Italian anarchists.

The Belgians rejoiced that the king was safe. Later in the day, in the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie before Tristan und Isolde was performed, the orchestra played the Brabançonne, which was sung loudly and ended with loud cheers and applause.[12]

Congo Free State

Leopold was the founder and sole owner of the Congo Free State, a private project undertaken on his own behalf.[13]:136 He used explorer Henry Morton Stanley to help him lay claim to the Congo, an area now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. At the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, the colonial nations of Europe authorised his claim by committing the Congo Free State to improving the lives of the native inhabitants.[13]:122–124

From the beginning, Leopold ignored these conditions. Millions of Congolese inhabitants, including children, were mutilated and killed.[13]:115,118,127 He ran the Congo using the mercenary Force Publique for his personal enrichment.[14] Failure to meet rubber collection quotas was punishable by death. Meanwhile, the Force Publique were required to provide the hand of their victims as proof when they had shot and killed someone, as it was believed that they would otherwise use the munitions (imported from Europe at considerable cost) for hunting. As a consequence, the rubber quotas were in part paid off in chopped-off hands.

He used great sums of the money from this exploitation for public and private construction projects in Belgium during this period. He donated the private buildings to the state before his death.

Leopold extracted a fortune from the Congo, initially by the collection of ivory, and after a rise in the price of rubber in the 1890s, by forced labour from the natives to harvest and process rubber. Under his regime millions of Congolese people died. Modern estimates range from one million to fifteen million, with a consensus growing around 10 million.[15]:25[16] Several historians argue against this figure due to the absence of reliable censuses, the enormous mortality of diseases such as smallpox or sleeping sickness and the fact that there were only 175 administrative agents in charge of rubber exploitation.[5][6]

Reports of deaths and abuse led to a major international scandal in the early 20th century, and Leopold was forced by the Belgian government to relinquish control of the colony to the civil administration in 1908.

Obtaining the Congo Free State

Leopold fervently believed that overseas colonies were the key to a country's greatness, and he worked tirelessly to acquire colonial territory for Belgium. Leopold eventually began to acquire a colony as a private citizen. The Belgian government lent him money for this venture.

In 1866, Leopold instructed the Belgian ambassador in Madrid to speak to Queen Isabella II of Spain about ceding the Philippines to Belgium. Knowing the situation fully, the ambassador did nothing. Leopold quickly replaced the ambassador with a more sympathetic individual to carry out his plan.[17] In 1868, when Isabella II was deposed as queen of Spain, Leopold tried to press his original plan to acquire the Philippines. But without funds, he was unsuccessful. Leopold then devised another unsuccessful plan to establish the Philippines as an independent state, which could then be ruled by a Belgian. When both of these plans failed, Leopold shifted his aspirations of colonisation to Africa.[17]

After numerous unsuccessful schemes to acquire colonies in Africa and Asia, in 1876 Leopold organized a private holding company disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Society, or the International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of the Congo. In 1878, under the auspices of the holding company, he hired explorer Henry Stanley to explore and establish a colony in the Congo region.[18]:62 Much diplomatic maneuvering among European nations resulted in the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 regarding African affairs, at which representatives of 14 European countries and the United States recognized Leopold as sovereign of most of the area to which he and Stanley had laid claim.[18]:84–87 On 5 February 1885, the Congo Free State, an area 76 times larger than Belgium, was established under Leopold II's personal rule and private army, the Force Publique.[18]:123–124

Lado Enclave

In 1894, King Leopold signed a treaty with Great Britain which conceded a strip of land on the Congo Free State's eastern border in exchange for the Lado Enclave, which provided access to the navigable Nile and extended the Free State's sphere of influence northwards into Sudan.[19] After rubber profits soared in 1895, Leopold ordered the organization of an expedition into the Lado Enclave, which had been overrun by Mahdist rebels since the outbreak of the Mahdist War in 1881. The expedition was composed of two columns: the first, under Belgian war hero Baron Dhanis, consisted of a sizable force, numbering around 3,000, and was to strike north through the jungle and attack the rebels at their base at Rejaf. The second, a much smaller force of 800, was led by Louis-Napoléon Chaltin and took the main road towards Rejaf. Both expeditions set out in December 1896.[20]

Although Leopold had initially planned for the expedition to carry on much farther than the Lado Enclave, hoping indeed to take Fashoda and then Khartoum,[21] Dhanis' column mutinied in February 1897, resulting in the death of several Belgian officers and the loss of his entire force. Nonetheless, Chaltin continued his advance, and on 17 February 1897, his outnumbered forces defeated the rebels in the Battle of Rejaf, securing the Lado Enclave as a Belgian territory until Leopold's death in 1909.[22]

Exploitation, atrocities, and death toll

Leopold amassed a huge personal fortune by exploiting the natural resources of the Congo. At first, ivory was exported, but this did not yield the expected levels of revenue. When the global demand for rubber exploded, attention shifted to the labor-intensive collection of sap from rubber plants. Abandoning the promises of the Berlin Conference in the late 1890s, the Free State government restricted foreign access and extorted forced labor from the natives. Abuses, especially in the rubber industry, included forced labour of the native population, beatings, widespread killings, and frequent mutilation when production quotas were not met.[23] Missionary John Harris of Baringa was so shocked by what he had encountered that he wrote to Leopold's chief agent in the Congo, saying:

I have just returned from a journey inland to the village of Insongo Mboyo. The abject misery and utter abandon is positively indescribable. I was so moved, Your Excellency, by the people's stories that I took the liberty of promising them that in future you will only kill them for crimes they commit.[24]

Estimates of the death toll range from one million to fifteen million,[25][26] since accurate records were not kept. Historians Louis and Stengers in 1968 stated that population figures at the start of Leopold's control are only "wild guesses", and that attempts by E. D. Morel and others to determine a figure for the loss of population were "but figments of the imagination".[27][28]

Adam Hochschild devotes a chapter of his book King Leopold's Ghost to the problem of estimating the death toll. He cites several recent lines of investigation, by anthropologist Jan Vansina and others, that examine local sources (police records, religious records, oral traditions, genealogies, personal diaries, and "many others"), which generally agree with the assessment of the 1919 Belgian government commission: roughly half the population perished during the Free State period. Hochshild points out that since the first official census by the Belgian authorities in 1924 put the population at about 10 million, these various approaches suggest a rough estimate of a population decline by 10 million.[18]:225–233

Smallpox epidemics and sleeping sickness also devastated the disrupted population.[29] By 1896, African trypanosomiasis had killed up to 5,000 Africans in the village of Lukolela on the Congo River. The mortality statistics were collected through the efforts of British consul Roger Casement, who found, for example, only 600 survivors of the disease in Lukolela in 1903.[30]

Criticism of the management of Congo

Inspired by works such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902), originally published as a three-part series in Blackwood’s Magazine (1899) and based on Conrad's experience as a steamer captain on the Congo 12 years earlier, international criticism of Leopold’s rule increased and mobilized. Reports of outrageous exploitation and widespread human rights abuses led the British Crown to appoint their consul Roger Casement to investigate conditions there. His extensive travels and interviews in the region resulted in the Casement Report, which detailed the extensive abuses under Leopold's regime.[31] A widespread war of words ensued. In Britain, former shipping clerk E. D. Morel with Casement's support founded the Congo Reform Association, the first mass human rights movement.[24] Supporters included American writer Mark Twain, whose stinging political satire entitled King Leopold's Soliloquy portrays the king arguing that bringing Christianity to the country outweighs a little starvation, and uses many of Leopold's own words against him.[32]

Writer Arthur Conan Doyle also criticised the "rubber regime" in his 1908 work The Crime of the Congo, written to aid the work of the Congo Reform Association. Doyle contrasted Leopold's rule to the British rule of Nigeria, arguing that decency required those who ruled primitive peoples to be concerned first with their uplift, not how much could be extracted from them. As Hochschild describes in King Leopold's Ghost, many of Leopold's policies, in particular those of colonial monopolies and forced labour, were influenced by Dutch practice in the East Indies.[18]:37 Similar methods of forced labour were employed to some degree by Germany, France, and Portugal where natural rubber occurred in their own colonies.[18]:280

Relinquishment of the Congo

International opposition and criticism from the Catholic Party, Progressive Liberals [33] and the Labour Party caused the Belgian parliament to compel the king to cede the Congo Free State to Belgium in 1908. The deal that led to the handover cost Belgium the considerable sum of 215.5 million Francs. This was used to discharge the debt of the Congo Free State and to pay out its bond holders as well as 45.5 million for Leopold's pet building projects in Belgium and a personal payment of 50 million to him.[18]:259 The Congo Free State was transformed into a Belgian colony known as the Belgian Congo under parliamentary control. Leopold went to great lengths to conceal potential evidence of wrongdoing during his time as ruler of his private colony. The entire archive of the Congo Free State was burned and he told his aide that even though the Congo had been taken from him, "they have no right to know what I did there".[18]:294 After gaining its independence in the mid-20th century, it was renamed three times: first, as the Republic of the Congo; second as Zaire, the name it retained under Mobutu Sese Seko's dictatorship; and third as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or DRC. (This is not to be confused with the neighboring Republic of the Congo, which was formerly a colony of France.)

Death and legacy

On 17 December 1909, Leopold II died at Laeken, and the Belgian crown passed to Albert, the son of Leopold's brother, Philippe, Count of Flanders. His funeral cortege was booed by the crowd.[34] Leopold's reign of exactly 44 years remains the longest in Belgian history. He was interred in the royal vault at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken in Brussels.

After the king's death and transfer of his private colony to Belgium, there occurred a "Great Forgetting".[35] Many Belgians in the 20th and 21st centuries remember Leopold II as the "Builder King" for his extensive public works projects. In the 1990s, the colonial Royal Museum for Central Africa made no mention of the atrocities committed in the Congo Free State, despite the museum's large collection of colonial objects. On the boardwalk of Blankenberge, a popular coastal resort, a monument shows a pair of colonists as heroes protecting a desperate Congolese woman and child with "civilization".[36] In Ostend, the beach promenade has a 1931 sculptural monument to Leopold II, showing Leopold and grateful Ostend fishermen and Congolese. The inscription accompanying the Congolese group notes: "De dank der Congolezen aan Leopold II om hen te hebben bevrijd van de slavernij onder de Arabieren" ("The gratitude of the Congolese to Leopold II for having liberated them from slavery under the Arabs"). In 2004, an activist group cut off the hand of the leftmost Congolese bronze figure, in protest against the atrocities committed in the Congo. The city council decided to keep the statue in its new form, without the hand.[37][38]

The debate over Leopold's legacy was reopened in 1999 with the publication of King Leopold's Ghost by American historian[39] Adam Hochschild, which recounts Leopold's plan to acquire the colony, the exploitation, and the large death toll. The book was controversial in Belgium but widely praised by American scholars and critics.[40][41][42][43]

Belgian member of the European Parliament and former Belgian foreign minister Louis Michel called Leopold II a "visionary hero." According to Michel, "To use the word 'genocide' in relation to the Congo is absolutely unacceptable and inappropriate. ... maybe colonisation was domineering and acquiring more power, but at a certain moment, it brought civilisation."[44] Michel's remarks were countered by several Belgian politicians. Senator Pol Van Den Driessche replied, "[A] great visionary? Absolutely not. What happened then was shameful. If we measured him against 21st century standards, it is likely that Leopold would be hauled before the International Criminal Court in the Hague."[44]

Statues in Congo

Leopold II remains a controversial figure in the Democratic Republic of Congo. His statue in the capital Kinshasa (known until 1966 as Leopoldville in his honor) was removed after independence. Congolese culture minister Christophe Muzungu decided to reinstate the statue in 2005. He noted that the beginning of the Free State had been a time of some economic and social progress. He argued that people should recognize some positive aspects of the king as well as the negative; but hours after the six-metre (20 ft) statue was installed near Kinshasa's central station, it was officially removed.[45]

Statues in Belgium

.jpg)

Several statues have been erected to honour the legacy of Leopold II in Belgium. Most of the statues date from the interwar period, the peak of colonial-patriotic propaganda. The monuments were supposed to help get rid of the scandal after international commotion about the atrocities in the Congo Free State and to raise people's enthusiasm for the colonialism in Belgian Congo.[46]

- The King Leopold II statue in Ostend which had been vandalised in 2004 and 2020.[47] In 2004 activist group De Stoete Ostendenoare symbolically cut off a bronze hand from one of the kneeling Congolese slaves who, as part of the 'Gratitude of the Congolese' group in the monument, honours Leopold II. This was a reference to how Congolese slaves' hands were cut off if they did not produce enough rubber during Leopold's colonial regime. The activists were willing to give the hand back if a historically correct sign would be placed near the statue.[48]

- Bust of Leopold in the King Albertpark (or Zuidpark) of Ghent (vandalised in 2018, 2019 and 2020).[49] This statue was vandalised in October and November 2018 and in July 2019, while activists demanded it be removed, along with all references to Leopold II, such as street names. Although the statue was not removed at that time, the city council placed a sign near the statue that reads: 'The city council regrets the many Congolese victims that have perished during the Free State.'[50] The bust was defaced with red paint again on 12 June 2020, and on 18 June the Ghent municipal board decided to remove it on 30 June 2020, the 60th anniversary of Congolese independence. The bust will possibly be moved to the Ghent City Museum (STAM).[51]

- Brussels Capital Region: In early June 2020, a majority in the Brussels Parliament requested a committee to be set up to 'decolonise the public sphere'.[52]

- Equestrian statue on the Throne Square in Brussels (vandalised in 2008, 2018, 2019 and 2020).[53] It had previously been vandalised several times, including with red paint by Théophile de Giraud in 2008,[54][55] again with red paint in 2018,[52] and with white paint in November 2019.[55]

- Standing statue in the King's Garden of Brussels (erected in 1969)[56]

- Bust in Brussels-Auderghem (Boulevard du Souverain) (erected in 1930)[57] Vandalised and knocked down, subsequently removed by the city in 2020.[58]

- Bust in the Duden Park in Brussels-Forest[59]

- Statue in Hasselt (vandalised as part of the George Floyd protests in 2020) [49]

- Standing statue in Ekeren, municipality of Antwerp (vandalised as part of the George Floyd protests and removed in 2020)[49]

- Statue in the Albertpark of Halle (vandalised in 2020)[53]

- Statue near the Africa Museum in Tervuren (vandalised in 2020)[53]

- Monument in Arlon, erected in 1951, featuring a quote from Leopold II: "I undertook the work of the Congo in the interest of civilisation and for the good of Belgium."[60]

- Standing statue at the Rue des Fossés in Mons (erected in 1957)[61]

- Standing statue on the Wiertz Square in Namur (erected in 1928)[62]

His controversial regime in the Congo Free State has motivated proposals for these statues to be removed, and the first of these was removed on 9 June 2020.[63][64]

During the international George Floyd protests against racism (May – June 2020), several statues of Leopold II were vandalised, while several petitions that called for the removal of some or all statues were signed by tens of thousands of Belgians.[63][49][47][65] Other petitions, also signed by tens of thousands, called for the statues to remain.[66][67]

As of 9 June 2020, authorities in Belgium gave way to public pressure and began removing some of the statues of Leopold, beginning with one in Ekeren in the municipality of Antwerp.[64]

Family

Leopold's sister became the Empress Carlota of Mexico. His first cousins included both Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and her husband Prince Albert, as well as King Fernando II of Portugal.

He had four children with Queen Marie-Henriette, of whom the youngest two have descendants living as of 2018:

- Princess Louise of Belgium, born in Brussels on 18 February 1858, and died at Wiesbaden on 1 March 1924. She married Prince Philipp of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on 4 February 1875, they had two children and divorced on 15 January 1906.

- Prince Leopold, Duke of Brabant, Count of Hainaut (as eldest son of the heir apparent), later Duke of Brabant (as heir apparent), born at Laeken on 12 June 1859, and died at Laeken on 22 January 1869, from pneumonia, after falling into a pond.

- Princess Stéphanie of Belgium, born at Laeken on 21 May 1864, and died at the Archabbey of Pannonhalma in Győr-Moson-Sopron, Hungary, on 23 August 1945. She married (1) Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, the heir apparent to the throne of Austria-Hungary . In 1889, he died in a suicide pact with his mistress, Baroness Mary Vetsera, at the Mayerling hunting lodge.[68] Stéphanie's second husband was (2) Elemér Edmund Graf Lónyay de Nagy-Lónya et Vásáros-Namény (created, in 1917, Prince Lónyay de Nagy-Lónya et Vásáros-Namény).

- Princess Clémentine of Belgium, born at Laeken on 30 July 1872, and died at Nice on 8 March 1955. She married Prince Napoléon Victor Jérôme Frédéric Bonaparte (1862–1926), head of the Bonaparte family. The current head of the Imperial family, Jean-Christophe, Prince Napoléon is a direct descendant of King Leopold II.

Leopold also fathered two sons by Caroline Lacroix. They were adopted in 1910 by Lacroix's second husband, Antoine Durrieux.[69] Leopold granted them courtesy titles that were honorary, as the parliament would not have supported any official act or decree:

Titles, styles, arms and honours

Titles and styles

.svg.png)

- 9 April 1835 – 16 December 1840: His Royal Highness The Crown Prince of Belgium, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Saxony

- 16 December 1840 – 17 December 1865: His Royal Highness The Duke of Brabant, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Saxony

- 17 December 1865 – 17 December 1909: His Majesty The King of the Belgians

Honours

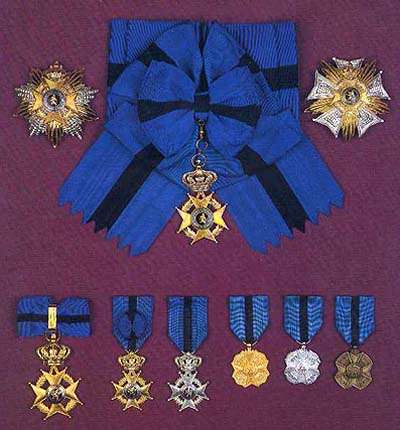

- National decorations[71]

- Grand Cordon of the Royal Order of Leopold, 9 April 1853;[72] Grand Master, 17 December 1865

- Founder and Grand Master of the Order of the Crown, 15 October 1897

- Founder and Grand Master of the Order of Leopold II, 24 August 1900

- Founder and Grand Master of the Royal Order of the Lion, 9 April 1891

- Founder and Grand Master of the Order of the African Star, 10 October 1908

- Foreign decorations[71]

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 1853

- Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1853

.svg.png)

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1862

- Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion, 1862

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Southern Cross

- Grand Cross of the Order of Pedro I

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

- (Cambodia): Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Cambodia

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore

- Grand Cross of the Griffon

.svg.png)

- Order of the Medjidie, 1st Class

- Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class

- Order of the Hanedan-i-Ali-Osman

- Grand Cordon of the Lion and the Sun

- Order of the August Portrait, 16 June 1873[86]

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, 6 September 1853

- Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 8 January 1866

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Black Eagle

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle

- Grand Commander of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern

.svg.png)

- Knight of St. Andrew

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

- Knight of the White Eagle

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Annunciation, 14 July 1855[89]

- Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 1855

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri, 9 September 1897[92]

- Grand Cross of the White Elephant

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Seraphim, 17 May 1852[94]

- Grand Cross of St. Olav, 13 July 1897

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of St. Joseph

- Civil and Military Order of Merit

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Arms

| Heraldry of Leopold II |

|---|

|

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Leopold II of Belgium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

Leopold in 1844, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter

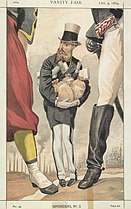

Leopold in 1844, by Franz Xaver Winterhalter Caricature of Leopold II. The caption reads: A constitutional king.

Caricature of Leopold II. The caption reads: A constitutional king. Caroline LaCroix, Leopold's mistress.

Caroline LaCroix, Leopold's mistress. Last photo of Leopold II before his death.

Last photo of Leopold II before his death.- Tomb of Leopold II and Marie Henriette.

Mutilated people from Congo Free State

Mutilated people from Congo Free State.jpg) Victim of the atrocities with a missionary, c. 1890–1910

Victim of the atrocities with a missionary, c. 1890–1910 Coronation Medal Leopold II – accession to the throne on 17 December 1865 – by Léopold Wiener.

Coronation Medal Leopold II – accession to the throne on 17 December 1865 – by Léopold Wiener.

See also

- Abir Congo Company

- Atrocities in the Congo Free State

- Émile Banning

- Congo Free State propaganda war

- Crown Council of Belgium

- Kings of Belgium family tree

References

- "Belgium's genocidal colonial legacy haunts the country's future". The Independent. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "The hidden holocaust". The Guardian. 13 May 1999. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- https://www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2020/06/05/leopold-ii-portret-en-controverse/

- Hochschild, Adam (1999). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa (1st ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-618-00190-3.

- Jean Stengers. "Critique de Livre de Hochschild" (PDF) (in French).

- Sophie Mignon. "Non, Léopold II n'est pas un génocidaire!" (in French).

-

- (in French) « mariage d'un palefrenier et d'une religieuse »

- "Leopold II". The Belgian Monarchy. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- (in French) « la patrie doit être forte, prospère, par conséquent posséder des débouchés à elle, belle et calme. » The King to the Count of Flanders, January 26, 1888; The Count of Flanders's papers.

- Stengers, Jean (2008). L'action du Roi en Belgique depuis 1831: pouvoir et influence [The action of the King in Belgium since 1831: power and influence] (in French) (3rd ed.). Brussels: Racine. pp. 123–24. ISBN 978-2-87386-567-2.

- Meuse (La) 17-11-1902

- Ewans, Sir Martin (2017). European Atrocity, African Catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and its Aftermath. Abingdon, England: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315829173. ISBN 978-1317849070.

- Ascherson (1999), p. 8.

- Jalata, Asafa (March 2013). "Colonial Terrorism, Global Capitalism and African Underdevelopment: 500 Years of Crimes Against African Peoples". Journal of Pan African Studies. 5 (9). ISSN 0888-6601.

- Stanley, Tim (October 2012). "Belgium's Heart of Darkness". History Today. 62 (10): 49. ISSN 0018-2753.

- Ocampo, Ambeth (2009). Looking Back. Mandaluyong, Philippines: Anvil Publishing. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-971-27-2336-0.

- Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Mariner. ISBN 978-0-330-49233-1. OCLC 50527720.

- Roger Louis, William (2006). Ends of British Imperialism. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-347-6. p. 68.

- Charles de Kavanagh Boulger, Demetrius (1898). The Congo State: Or, The Growth of Civilisation in Central Africa. Congo: W. Thacker & Company. ISBN 0-217-57889-6. p. 214.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992). The Scramble for Africa. Avon Books. ISBN 978-0-380-71999-0. pp. 525–26.

- "Lado Enclave". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 19 July 2011.

- Neal Ascherson, The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo (Granta Books, 1999)

- Dummett, Mark (24 February 2004). "King Leopold's legacy of DR Congo violence". BBC. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- Forbath, Peter (1977). The River Congo: The Discovery, Exploration and Exploitation of the World's Most Dramatic Rivers. Harper & Row. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-06-122490-4.

- Wertham, Fredric (1968). A Sign For Cain: An Exploration of Human Violence. ISBN 978-0-7091-0232-8.

- Louis, William Roger; Stengers, Jean (1968). E. D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement. London: Clarendon. pp. 252–57. OCLC 685226763.

- Guy Vanthemsche (2012). Belgium and the Congo, 1885-1980. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521194211.

- "The 'Leopold II' concession system exported to French Congo with as example the Mpoko Company" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- "Le rapport Casement annoté par A. Schorochoff" (PDF). Posted at the website for the Royal Union for Overseas Colonies, http://www.urome.be.

- Ascherson, pp. 250–60.

- "Time". 16 May 1955. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- Lauwers Nathan; Georges Lorand (1860–1918): Een transnationale progressieve liberaal; VUB; 2016

- Dargis, Manohla (21 October 2005). "The Horrors of Belgium's Congo". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- Hochschild (1998), King Leopold's Ghost

- "Monument to De Bruyne and Lippens".

- Pieter De Vos. "Sikitiko" (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 August 2012.

De dank der Congolezen aan Leopold II om hen te hebben bevrijd van de slavernij onder de Arabieren (1:10)

- "Leopold II krijgt zijn hand terug als Oostende zwicht" [Oostende herstelt afgehakte hand van Leopold II niet] (in Dutch). 22 June 2004. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "'Spain in Our Hearts,' by Adam Hochschild". Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- Jeremy Harding (20 September 1998). "Into Africa". New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 September 2001. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

a superb synoptic history of European misdemeanor in central Africa

- Michiko Kakutani (1 September 1998). "Genocide With Spin Control". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 April 2001. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

Hochschild has stitched it together into a vivid, novelistic narrative

- Luc Sante (27 September 1998). "Leopold's Heart of Darkness". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

'King Leopold's Ghost' is an absorbing and horrifying account

- Godwin Rapando Murunga (1999). "King Leopold's Ghost (review)". African Studies Quarterly. 3 (2). Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

King Leopold's Ghost tells the story of the Congo with fresh and critical insights, bringing new analysis to this topic.

- Phillips, Leigh (22 June 2010). "Ex-commissioner calls Congo's colonial master a 'visionary hero'". EU Observer. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- Vasagar, Jeevan (4 February 2005). "Leopold reigns for a day in Kinshasa". The Guardian.

- Yolan Devriendt (2018). "BELGISCHE KOLONIALE GESCHIEDENIS IN HET KATHOLIEK MIDDELBAAR ONDERWIJS: VERGETEN VERHAAL OF KRITISCH DISCOURS?" (PDF) (in Dutch). p. 13.

- "Het Debat. Moeten standbeelden van Leopold II en andere bedenkelijke historische figuren verdwijnen uit het straatbeeld?". Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 6 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Douglas De Coninck (11 August 2014). "Hoe Oostendse activisten met een afgehakte hand de puntjes op de i zetten". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Al meer dan 16.000 handtekeningen voor petitie om standbeelden Leopold II uit Brussel weg te nemen, Tommelein wil beeld in Oostende niet verwijderen". Het Laatste Nieuws (in Dutch). 3 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Sabine Van Damme (2 June 2020). "Standbeeld Leopold II opnieuw beklad, nu naar aanleiding van dood George Floyd in Verenigde Staten". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Tuly Salumu & Bert Staes (18 June 2020). "Gent haalt beeld Leopold II weg: "Een dergelijk figuur kunnen we niet langer eren"". Het Nieuwsblad (in Dutch). Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Brusselse meerderheid vraagt dekolonisering van openbare ruimte". Bruzz (in Dutch). 4 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Steeds meer protest in België tegen standbeelden Leopold II". NOS (in Dutch). 5 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Congo: Histoire blanche, voix noires, zones grises" (PDF). Télé-Moustique (in French). 12 November 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Siebe Jonckheere (22 November 2019). "De schuld in de onschuld van een straatnaam". Krant van West-Vlaanderen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Item of the park on irismonument.be

- "Commission royale des monuments et des sites". Bulletin des commissions royales d'art et d'archéologie (in French). 69: 30. 1930. (Retrieved 5 June 2020)

- "Statue de Léopold II déboulonnée à Auderghem : Ce n'est pas comme ça qu'on procède dans une démocratie". RTBF Info (in French). 12 June 2020.

- "Forest - Parc Duden". www.irismonument.be.

- "Monument au roi Léopold II – Arlon". Be=Monumen (in French). 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Monument au roi Léopold II – Mons". Be=Monumen (in French). 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- http://lampspw.wallonie.be/dgo4/site_ipic/index.php/pdf/fiche/92094-INV-1952-01

- Teri Schultz (5 June 2020). "Belgians Target Some Royal Monuments In Black Lives Matter Protest". NPR. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Burned Leopold II statue removed from Antwerp square". The Brussels Times. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Burno Struys (6 June 2020). "Dit zijn de organisatoren van de Belgische Black Lives Matter-betogingen". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Pourquoi les opposants à Léopold II continuent-ils à vandaliser les statues de l'ancien Roi ?". RTBF (in French). 6 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Jean-Luc Bodeux (18 June 2020). "Arlon: pétition et contre-pétition autour de Léopold II". Le Soir (in French). Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- As documented in several autograph letters by the two unfortunate lovers ANSA newsbrief (in Italian)

- "Le Petit Gotha"

- "George Washington Williams's Open Letter to King Leopold on the Congo". blackpast.org. 1890. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- A. Manceaux, Imprimeur-Libraire, ed. (1905). Almanach de poche de Bruxelles et de ses faubourgs (in French). Brussels. pp. 6–7.

- Almanach royal officiel, publié, exécution d'un arrête du roi, Volume 1; Tarlier, 1854

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch für das Herzogthum Anhalt (1894), "Herzoglicher Haus-Orden Albrecht des Bären" p. 16

- "Ritter-Orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch der Österreichisch-Ungarischen Monarchie, 1908, pp. 53, 57, retrieved 5 November 2019

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1873), "Großherzogliche Orden" pp. 59, 74

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Bayern (1906), "Königliche Orden" p. 7

- Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 273. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- Staatshandbücher für das Herzogtum Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (1854), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 26

- Staat Hannover (1865). Hof- und Staatshandbuch für das Königreich Hannover: 1865. Berenberg. pp. 38, 79.

- Kalakaua to his sister, 28 July 1881, quoted in Greer, Richard A. (editor, 1967) "The Royal Tourist—Kalakaua's Letters Home from Tokio to London", Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 5, p. 102

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Hessen (1879), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" p. 12

- Kurfürstlich Hessisches Hof- und Staatshandbuch: 1866. Waisenhaus. 1866.

- Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1909) p. 19

- "Seccion IV: Ordenes del Imperio", Almanaque imperial para el año 1866 (in Spanish), 1866, p. 243, retrieved 29 April 2020

- Staat Oldenburg (1873). Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Oldenburg: für ... 1872/73. Schulze. p. 30.

- Naser al-Din Shah Qajar (1874). "Chapter III: Prussia, Germany, Belgium". The Diary of H.M. The Shah of Persia during his tour through Europe in A.D. 1873: A verbatim translation. Translated by James Redhouse. London: John Murray. p. 130.

- Bragança, Jose Vicente de (2014). "Agraciamentos Portugueses Aos Príncipes da Casa Saxe-Coburgo-Gota" [Portuguese Honours awarded to Princes of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 9–10: 9–10. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Ordinul Carol I" [Order of Carol I]. Familia Regală a României (in Romanian). Bucharest. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Cibrario, Luigi (1869). Notizia storica del nobilissimo ordine supremo della santissima Annunziata. Sunto degli statuti, catalogo dei cavalieri (in Italian). Eredi Botta. p. 115. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1855), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 12

- Staatshandbuch für den Freistaat Sachsen: 1865/66. Heinrich. 1866. p. 4.

- Royal Thai Government Gazette (14 May 1899). "พระราชทานเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์ที่ประเทศยุโรป (ต่อแผ่นที่ ๖ หน้า ๘๓)" (PDF) (in Thai). Retrieved 8 May 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III". Guía Oficial de España (in Spanish). 1887. p. 153. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- Sveriges och Norges statskalender. Liberförlag. 1874. p. 468.

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 63

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Württemberg (1907), "Königliche Orden" p. 27

Bibliography

- Ascherson, Neal: The King Incorporated, Allen & Unwin, 1963. ISBN 1-86207-290-6 (1999 Granta edition).

- Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Mariner Books, 1998. ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- Petringa, Maria: Brazza, A Life for Africa, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4259-1198-0

- Wm. Roger Louis and Jean Stengers: E.D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement, Clarendon Press Oxford, 1968.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas and Michael O’Sullivan, eds: The Eyes of Another Race: Roger Casement's Congo Report and 1903 Diary. University College Dublin Press, 2004. ISBN 1-900621-99-1.

- Ó Síocháin, Séamas: Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 2008.

- Roes, Aldwin (2010). "Towards a History of Mass Violence in the Etat Indépendant du Congo, 1885–1908" (PDF). South African Historical Journal. 62 (4): 634–70. doi:10.1080/02582473.2010.519937.

- Stanard, Matthew G. Selling the Congo: A history of European pro-empire propaganda and the making of Belgian imperialism (U of Nebraska Press, 2012)

- Vanthemsche, Guy (2012). Belgium and the Congo, 1885–1980 (Cambridge UP, ISBN 978-0521194211).

- Vanthemsche, Guy (2006) 'The historiography of Belgian colonialism in the Congo" in C Levai ed., Europe and the World in European Historiography (Pisa University Press), pp. 89–119. online

- Viaene, Vincent. "King Leopold's imperialism and the origins of the Belgian colonial party, 1860–1905." Journal of Modern History 80.4 (2008): 741–90.

External links

- Archive Léopold II, Royal museum of central Africa

- Official biography from the Belgian Royal Family website

- "The Political Economy of Power" Interview with political scientist Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, with a discussion of Leopold halfway through

- Interview with King Leopold II Publishers' Press, 1906

- Mass crimes against humanity in the Congo Free State

- Congo: White king, red rubber, black death A 2003 documentary by Peter Bate on Leopold II and the Congo

- The Crime of the Congo, 1909, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Archive.org

- Grant, Kevin (2001). "Christian critics of empire: Missionaries, lantern lectures, and the Congo reform campaign in Britain". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 29 (2): 27–58. doi:10.1080/03086530108583118.

- Peffer, John (2008). "Snap of the Whip/Crossroads of Shame: Flogging, Photography, and the Representation of Atrocity in the Congo Reform Campaign". Visual Anthropology Review. 24: 55–77. doi:10.1111/j.1548-7458.2008.00005.x.

- van den Braembussche, Antoon (2002). "The Silence of Belgium: Taboo and Trauma in Belgian Memory". Yale French Studies (102): 34–52. JSTOR 3090591.

- Weisbord, Robert G. (2003). "The King, the Cardinal and the Pope: Leopold II's genocide in the Congo and the Vatican". Journal of Genocide Research. 5: 35–45. doi:10.1080/14623520305651.

- Langbein, John H. (January 1976). "The Historical Origins of the Sanction of Imprisonment for Serious Crime". The Journal of Legal Studies. 5 (1): 35–60. doi:10.1086/467543. JSTOR 724073.

- Gewald, Jan-Bart (2006). "More than Red Rubber and Figures Alone: A Critical Appraisal of the Memory of the Congo Exhibition at the Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 39 (3): 471–86. JSTOR 40034827.

- Pavlakis, Dean (2010). "The Development of British Overseas Humanitarianism and the Congo Reform Campaign". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 11 (1). doi:10.1353/cch.0.0102.

- Newspaper clippings about Leopold II of Belgium in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

Leopold II of Belgium Cadet branch of the House of Wettin Born: 9 April 1835 Died: 17 December 1909 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Leopold I |

King of the Belgians 1865–1909 |

Succeeded by Albert I |

| Belgian royalty | ||

| New title | Duke of Brabant 1840–1865 |

Succeeded by Leopold |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)