Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Neapolitan: Regno d’ ’e Ddoje Sicilie; Sicilian: Regnu dî Dui Sicili; Italian: Regno delle Due Sicilie; Spanish: Reino de las Dos Sicilias)[1] was a kingdom located in Southern Italy from 1816–1860.[2] The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy prior to Italian unification, comprising Sicily and all of Peninsula Italy south of the Papal States, covering most of the area of today's Mezzogiorno.

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies Regno delle Due Sicilie (Italian) Regno d’ ’e Ddoje Sicilie (Neapolitan) Regnu dî Dui Sicili (Sicilian) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1816–1861 | |||||||||||

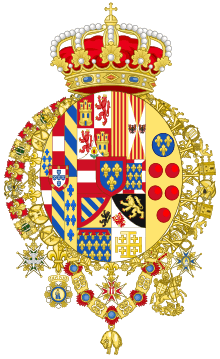

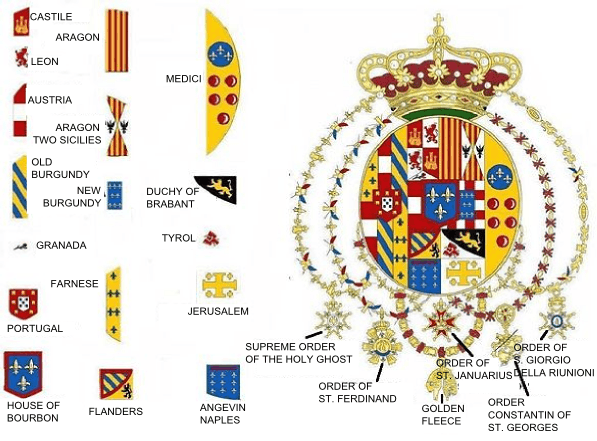

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

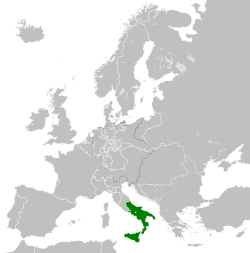

Location of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies within Europe in 1839 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Palermo (1816–1817) Naples (1817–1861) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Neapolitan Sicilian Italian Molise Croatian Gallo-Italic of Sicily Gallo-Italic of Basilicata Franco-Provençal Occitan Griko Greek-Bovesian Arbëresh | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1816–1848; 1849–1861) Constitutional monarchy (1848–1849) | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1816–1825 | Ferdinand I (first) | ||||||||||

• 1859–1861 | Francis II (last) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Edict of Ferdinand IV of Naples | 12 December 1816 | ||||||||||

| 5 May 1860 | |||||||||||

| 17 March 1861 | |||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• Estimate | 9,281,279 (1859/60) | ||||||||||

| Currency | Two Sicilies ducat | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Italy Croatia[a] | ||||||||||

The kingdom was formed when the Kingdom of Sicily merged with the Kingdom of Naples, which was officially known as the Kingdom of Sicily. Since both kingdoms were named Sicily, they were collectively known as the "Two Sicilies" (Utraque Sicilia, literally "both Sicilies"), and the unified kingdom adopted this name. The King of the Two Sicilies was overthrown by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1860, after which the people voted in a plebiscite to join the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia. The annexation of the Two Sicilies completed the first phase of Italian unification, and the new Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed in 1861.

The Two Sicilies were heavily agricultural, like the other Italian states.[3]

Name

The name "Two Sicilies" originated from the partition of the medieval Kingdom of Sicily. Until 1285, the island of Sicily and the Mezzogiorno were constituent parts of the Kingdom of Sicily. As a result of the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302),[4] the King of Sicily lost the Island of Sicily (also called Trinacria) to the Crown of Aragon, but remained ruler over the peninsular part of the realm. Although his territory became known unofficially as the Kingdom of Naples, he and his successors never gave up the title "King of Sicily" and still officially referred to their realm as the "Kingdom of Sicily". At the same time, the Aragonese rulers of the Island of Sicily also called their realm the "Kingdom of Sicily". Thus, there were two kingdoms called "Sicily":[4] hence, the Two Sicilies.

Background

Origins of the two kingdoms

In 1130 the Norman king Roger II formed the Kingdom of Sicily by combining the County of Sicily with the southern part of the Italian Peninsula (then known as the Duchy of Apulia and Calabria) as well as with the Maltese Islands. The capital of this kingdom was Palermo — which is on the island of Sicily.[5][6][7]

During the reign of Charles I of Anjou (1266–1285),[8] the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302) split the kingdom.[9][10] Charles, who was of French origin, lost the island of Sicily to the House of Barcelona, who were from Aragon and Catalan.[10][11] Charles remained king of the peninsular region, which became informally known as the Kingdom of Naples. Officially Charles never gave up the title of "The Kingdom of Sicily", thus there existed two separate kingdoms calling themselves "Sicily".[12]

Aragonese and Spanish direct rule

Only with the Peace of Caltabellotta (1302), sponsored by Pope Boniface VIII, did the two kings of "Sicily" recognize each other's legitimacy; the island kingdom then became the "Kingdom of Trinacria" in official contexts,[13] though the populace still called it Sicily.[4] In 1442, Alfonso V of Aragon, king of insular Sicily, conquered Naples and became king of both.[14][15]

Alfonso V called his kingdom in Latin "Regnum Utriusque Siciliæ", meaning "Kingdom of both Sicilies".[16] At the death of Alfonso in 1458, the kingdom again became divided between his brother John II of Aragon, who kept the island of Sicily, and his illegitimate son Ferdinand, who became King of Naples.[17][9] In 1501, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, the son of John II, agreed to help Louis XII of France conquer Naples and Milan. After Frederick IV was forced to abdicate, the French took power, and Louis reigned as Louis III of Naples for three years. Negotiations to divide the region failed, and the French soon began unsuccessful attempts to force the Spanish out of the peninsula.[18]

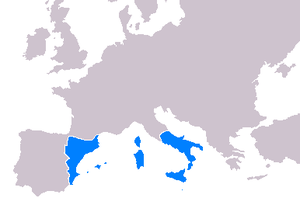

After the French lost the Battle of Garigliano (1503), they left the kingdom. Ferdinand II then re-united the two areas into one kingdom.[18] From 1516, when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor became the first King of Spain, both Naples and Sicily came under direct Spanish rule.[19] In 1530 Charles V granted the islands of Malta and Gozo, which had been part of the Kingdom of Sicily, to the Knights Hospitaller (thereafter known as the Order of Malta).[20] At the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 granted Sicily to the Duke of Savoy,[21][22] until the Treaty of Rastatt in 1714 left Naples to the Emperor Charles VI.[23] In the 1720 Treaty of The Hague, the Emperor and Savoy exchanged Sicily for Sardinia, thus reuniting Naples and Sicily.[24][25]

History

Unification of the Crowns

In 1735, during the War of the Polish Succession, Charles, Duke of Parma, defeated the occupying Austrians and became Charles III of Naples and Sicily.[26][27] In 1759, Charles became King Carlos III of Spain and resigned Sicily and Naples to his younger son, who became Ferdinand III of Sicily and Ferdinand IV of Naples.[27][28]

In January 1799, Jean-Étienne Championnet, a general of the French First Republic, captured Naples and proclaimed the Parthenopaean Republic, a French client state, as successor to the kingdom.[29][30] King Ferdinand fled from Naples to Sicily.[31] The French Directory had not authorized Championnet to establish a republic, and recalled him to France. The Republic then collapsed in June 1799.[30] In an 1806 invasion, Napoleon, by then French Emperor, again dethroned King Ferdinand and appointed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, as King of Naples.[32] In the Edict of Bayonne of 1808 Napoleon moved Joseph to Spain and appointed their brother-in-law, Joachim Murat, as King of the Two Sicilies, though this only meant control of the mainland portion of the kingdom.[33][34] While Bonaparte and Murat were in power, Ferdinand remained in Sicily, with Palermo as his capital.[28][35]

Murat remained in power and joined the Sixth Coalition against Napoleon in 1813. The coalition resulted in the defeat of Napoleon and his exile to Elba. When he escaped and took power for the Hundred Days, Murat again sided with Napoleon. He was soon executed,[36][37] and the Congress of Vienna restored Ferdinand in 1815.[38] He established a concordat with the Papal States, which previously had a claim to the land.[39]

Early history

Under Joseph Bonaparte and Joachim Murat, Naples had undergone many reforms. Bonaparte refused to impose the Continental System on the peninsula, which promoted stability in the region. Laws were standardized and cataloged, finances were balanced, taxes were reorganized, education was improved, and the government was consolidated into a civil administration. Though Murat had attempted to strengthen the military, when Ferdinand returned to power, the region was essentially defenseless.[36][40]

Expedition of the Thousand

Between 1816 and 1848, the island of Sicily experienced three popular revolts against Bourbon rule, including the insurrection of 1847 and the revolution of independence of 1848, when the island was fully independent of Bourbon control for 16 months.

The end of the kingdom came only with the Expedition of the Thousand in 1860, led by Garibaldi – an icon of Italian unification – with the support of the House of Savoy and their Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. The expedition resulted in a striking series of defeats for the Sicilian armies facing the growing troops of Garibaldi. After the capture of Palermo and Sicily, Garibaldi disembarked in Calabria and moved towards Naples, while in the meantime the Piedmontese also invaded the Kingdom from the Marche. The last battles took place at Volturnus in 1860 and at the siege of Gaeta, where King Francis II (reigned 1859–1861) had sought shelter, hoping for French help, which never came. The last towns to resist Garibaldi's expedition, Messina and Civitella del Tronto, capitulated on 13 March 1861 and on 20 March 1861 respectively. The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies dissolved and the new Kingdom of Italy, founded in the same year annexed its territory. The fall of the Sicilian aristocracy in the face of Garibaldi's invasion forms the subject of the novel The Leopard by Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa and its film adaptation.

Historical population

| Year | Kingdom of Naples | Kingdom of Sicily | Total | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1819 | 5,733,430 | – |

– |

[41] |

| 1827 | – |

– |

~7,420,000 | [42] |

| 1828 | 6,177,598 | – |

– |

[41] |

| 1832 | – |

1,906,033 | – |

[41] |

| 1839 | 6,113,259 | – |

~8,000,000 | [41][43] |

| 1840 | 6,117,598 | ~<1,800,000 (est.) | 7,917,598 | [44] |

| 1848 | 6,382,706 | 2,046,610 | 8,429,316 | [43] |

| 1851 | 6,612,892 | 2,041,583 | 8,704,472 | [45] |

| 1856 | 6,886,030 | 2,231,020 | 9,117,050 | [46] |

| 1859/60 | 6,986,906 | 2,294,373 | 9,281,279 | [47] |

The kingdom had a large population, at least three times as large as any other contemporary Italian state. At its peak, the kingdom had a military 100,000 soldiers strong, and a large bureaucracy.[48] Naples was the largest city in the kingdom and the third largest city in Europe. The second largest city, Palermo, was the third largest in Italy.[49] In the 1800s, the kingdom experienced large population growth, rising from approximately five to seven million.[50] It held approximately 36% of Italy's population around 1850.[51]

Because the kingdom did not establish a statistical department until after 1848,[52] most population statistics prior to that year are estimates and censuses undertaken were thought by contemporaries to be inaccurate.[41]

Geography

Departments

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments[40][53] and Sicily was divided into seven departments.[54] The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia, the departments became provinces of Italy, according to the Rattazzi law.

|

|

- The city of Benevento was formally included in this department, but it was occupied by the Papal States and was de facto an exclave of that country.

Economy

Industry

Industry was the largest source of income if compared with the other preunitarian states. One of the most important industrial complexes in the kingdom was the shipyard of Castellammare di Stabia, which employed 1800 workers. The engineering factory of Pietrarsa was the largest industrial plant in the Italian peninsula, producing tools, cannons, rails, locomotives. The complex also included a school for train drivers, and naval engineers and, thanks to this school, the kingdom was able to replace the English personnel who had been necessary until then. The first steamboat with screw propulsion known in the Mediterranean Sea was the "Giglio delle Onde", with mail delivery and passenger transport purposes after 1847.

In Calabria, the Fonderia Ferdinandea was a large foundry where cast iron was produced. The Reali ferriere ed Officine di Mongiana was an iron foundry and weapons factory. Founded in 1770, it employed 1600 workers in 1860 and closed in 1880. In Sicily (near Catania and Agrigento), sulfur was mined to make gunpowder. The Sicilian mines were able to satisfy most of the global demand for sulfur. Silk cloth production was focused in San Leucio (near Caserta). The region of Basilicata also had several mills in Potenza and San Chirico Raparo, where cotton, wool and silk were processed. Food processing was widespread, especially near Naples (Torre Annunziata and Gragnano).

Sulfur

The kingdom maintained a large sulfur mining industry. In industrializing Britain, with the repeal of tariffs on salt in 1824, demand for sulfur from Sicily surged upward. The increasing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and transportation of the sulfur, coupled with the failure of this lucrative export to transform Sicily's backward and impoverished economy, led to the 'Sulfur Crisis' of 1840, when King Ferdinand II gave a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French firm, violating an earlier 1816 trade agreement with Britain. A peaceful solution was eventually negotiated by France.[55][56]

Transport

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The Kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards, by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain, Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

Technological and scientific achievements

The kingdom achieved several scientific and technological accomplishments, such as the first steamboat in the Mediterrean Sea (1818),[57][58] built in the shipyard of Stanislao Filosa al ponte di Vigliena, near Naples, and the first railway in the Italian peninsula (1839), which connected Naples to Portici.[59] However, until the Italian unification, the railway development was highly limited. In the year 1859, the kingdom had only 99 kilometers of rail, compared to the 850 kilometers of Piedmont.[60] This was because the kingdom could count on a very large and efficient merchant navy, which was able to compensate for the need for railways. Also, southern landscape was mainly mountainous making the process of building railways quite difficult, as building railway tunnels was much harder at the time. Other achievements included the first volcano observatory in the world, l'Osservatorio Vesuviano (1841),[61][62]. The rails for the first Italian railways were built in Mongiana as well. All the rails of the old railways that went from the south to as far as Bologna were built in Mongiana.

Monarchy

Kings of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand I, 1816–1825

Ferdinand I, 1816–1825 Francis I, 1825–1830

Francis I, 1825–1830 Ferdinand II, 1830–1859

Ferdinand II, 1830–1859 Francis II, 1859–1861

Francis II, 1859–1861

In 1860–61 with influence from Great Britain and Gladstone's propaganda, the kingdom was absorbed into the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the title dropped. It is still claimed by the head of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies.

Titles of King of the Two Sicilies

Francis I or Francis II, King of the Two Sicilies, of Jerusalem, etc., Duke of Parma, Piacenza, Castro, etc., Hereditary Grand Prince of Tuscany, etc.[63]

House of Bourbon in exile

Some sovereigns continued to maintain diplomatic relations with the exiled court, including the Emperor of Austria, the Kings of Bavaria, Württemberg and Hanover, the Queen of Spain, the Emperor of Russia, and the Papacy.

Flags of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

.svg.png) 1816–1848; 1849–1860 flag

1816–1848; 1849–1860 flag.svg.png) 1848–1849 flag

1848–1849 flag.svg.png) 1860–1861 flag

1860–1861 flag Framed antique flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (c. 1830s) discovered in Palermo.

Framed antique flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (c. 1830s) discovered in Palermo.

Orders of knighthood

- Order of St. Januarius

- Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George

- Order of Saint George and Reunion

- Order of Saint Ferdinand and Merit

- Royal Order of Francis I

Further reading

- The Volcano Lover, a novel by Susan Sontag, is set in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies during the Napoleonic era.

See also

- Dictatorship of Garibaldi

- List of historic states of Italy

- List of monarchs of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

- Southern Italy

- Southern Italy autonomist movements

- Two Sicilies national football team

- Army of the Two Sicilies

- Real Marina (Kingdom of the Two Sicilies)

- Line of succession to the former throne of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

References

- Swinburne, Henry (1790). Travels in the Two Sicilies (1790). British Library.

two sicilies.

- De Sangro, Michele (2003). I Borboni nel Regno delle Due Sicilie (in Italian). Lecce: Edizioni Caponi.

- Nicola Zitara. "La legge di Archimede: L'accumulazione selvaggia nell'Italia unificata e la nascita del colonialismo interno" (PDF) (in Italian). Eleaml-Fora!.

- "Sicilian History". Dieli.net. 7 October 2007.

- Oldfield, Paul (2017). "Alexander of Telese's Encomium of Capua and the Formation of the Kingdom of Sicily" (PDF). History: 183–200. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 April 2019.

- Oldfield, Paul (2015). "Italo-Norman Empire". The Encyclopedia of Empire: A-C. The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe004. ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4.

- "Kingdom of the Two Sicilies | historical kingdom, Italy". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Fleck, CathleenA (5 July 2017). The Clement Bible at the Medieval Courts of Naples and Avignon: "A Story of Papal Power, Royal Prestige, and Patronage ". Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-351-54553-2.

- Shneidman, J. Lee (1960). "Aragon and the War of the Sicilian Vespers". The Historian. 22 (3): 250–263. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1960.tb01657.x. ISSN 0018-2370. JSTOR 24437629.

- Kohn, George Childs (31 October 2013). Dictionary of Wars. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 978-1-135-95494-9.

- Kleinhenz, Christopher (2 August 2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 1103. ISBN 978-1-135-94880-1.

- Sakellariou, Eleni (9 December 2011). Southern Italy in the Late Middle Ages: Demographic, Institutional and Economic Change in the Kingdom of Naples, c.1440-c.1530. BRILL. p. 63. ISBN 978-90-04-22405-6.

- Kleinhenz, Christopher (2 August 2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 847. ISBN 978-1-135-94879-5.

- O'Callaghan, Joseph F. (12 November 2013). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-6871-1.

- Hooper, John (29 January 2015). The Italians. Penguin. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-698-18364-3.

- Davies, Norman (5 January 2012). Vanished Kingdoms: The Rise and Fall of States and Nations. Penguin. p. 210. ISBN 978-1-101-54534-8.

- Kellogg, Day Otis; Smith, William Robertson (1902). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: latest edition. A dictionary of arts, sciences and general literature. Werner. pp. 478.

- Tarver, H. Micheal; Slape, Emily (25 July 2016). The Spanish Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-61069-422-3.

- "Italy - The age of Charles V". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Badger, George Percy (1838). Description of Malta and Gozo. M. Weiss. pp. 19–20.

- Memoirs of the affairs of Europe from the Peace of Utrecht. Murray. 1824. p. 426.

- Dadson, Trevor J. (2 December 2017). Britain, Spain and the Treaty of Utrecht 1713-2013. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-19133-3.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (22 September 2015). Wars That Changed History: 50 of the World's Greatest Conflicts: 50 of the World's Greatest Conflicts. ABC-CLIO. p. 270. ISBN 978-1-61069-786-6.

- Williams, Henry Smith (1907). Italy. The Times. p. 670.

- Blackmore, David S. T. (10 January 2014). Warfare on the Mediterranean in the Age of Sail: A History, 1571-1866. McFarland. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-7864-5784-7.

- Black, Jeremy (1986). "British Neutrality in the War of the Polish Succession, 1733-1735". The International History Review. 8 (3): 345–366. doi:10.1080/07075332.1986.9640416. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40105627.

- Hearder, Harry; Morris, Jonathan (13 December 2001). Italy: A Short History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 141, 143. ISBN 978-0-521-00072-7.

- "Term details". British Museum. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Atkin, Nicholas; Biddiss, Michael; Tallett, Frank (23 May 2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-9072-8.

- Polasky, Janet L. (2015). Revolutions Without Borders: The Call to Liberty in the Atlantic World. Yale University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-300-20894-8.

- The Cambridge Modern History. CUP Archive. 1902. pp. 779.

- Abbott, John Stevens Cabot (1897). Joseph Bonaparte. Harper. pp. 105.

Naples (1806) Joseph Bonaparte.

- Colletta, Pietro (1858). History of the Kingdom of Naples (1858). University of Michigan.

Edict of Bayonne.

- Colletta, Pietro (1858). History of the kingdom of Naples: 1734-1825. T. Constable and Co. pp. 77–78.

- Nicolson, Harold (2000). The Congress of Vienna: A Study in Allied Unity, 1812-1822. Grove Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-8021-3744-9.

- Meeks, Joshua (15 December 2019). Napoléon Bonaparte: A Reference Guide to His Life and Works. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-5381-1351-6.

- "Napoleonic Period Collection". Washington University Library. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- Davis, John Anthony (2000). Italy in the Nineteenth Century: 1796-1900. Oxford University Press. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-19-873128-3.

- Blanch, L. Luigi de' Medici come uomo di stato e amministratore. Archivio Storico per le Province Napoletane. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- Goodwin, John (1842). "Progress of the Two Sicilies Under the Spanish Bourbons, from the Year 1734-35 to 1840". Journal of the Statistical Society of London. 5 (1): 47–73. doi:10.2307/2337950. ISSN 0959-5341. JSTOR 2337950.

- Macgregor, John (1850). Commercial Statistics: A Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs, of All Nations. Including All British Commercial Treaties with Foreign States. Whittaker and Company. pp. 18.

- partington, charles F. (1836). The british cyclopedia of literature, history,geography, law ,and politics. p. 553.

- Berkeley, G. F.-H.; Berkeley, George Fitz-Hardinge; Berkeley, Joan (1968). Italy in the Making 1815 to 1846. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-07427-8.

- Commercial Statistics: A Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs ... of All Nations ... C. Knight and Company. 1844. p. 18.

- The Popular Encyclopedia: Or, Conversations Lexicon. Blackie. 1862. p. 246.

- Russell, John (1870). Selections from Speeches of Earl Russell 1817 to 1841 and from Despatches 1859 to 1865: With Introductions. In 2 Volumes. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 223.

- Mezzogiorno d'Europa. 1983. p. 473.

- Ziblatt, Daniel (21 January 2008). Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism. Princeton University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4008-2724-4.

- Hearder, Harry (22 July 2014). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento 1790 - 1870. Routledge. pp. 125–6. ISBN 978-1-317-87206-1.

- Astarita, Tommaso (17 July 2006). Between Salt Water and Holy Water: A History of Southern Italy. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-25432-7.

kingdom of the two sicilies population.

- Toniolo, Gianni (14 October 2014). An Economic History of Liberal Italy (Routledge Revivals): 1850-1918. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-317-56953-4.

- House Documents. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1870. p. 19.

- Pompilio Petitti (1851). Repertorio amministrativo ossia collezione di leggi, decreti, reali rescritti ecc. sull'amministrazione civile del Regno delle Due Sicilie, vol. 1 (in Italian). Napoli: Stabilimento Migliaccio. p. 1.

- Pompilio Petitti (1851). Repertorio amministrativo ossia collezione di leggi, decreti, reali rescritti ecc. sull'amministrazione civile del Regno delle Due Sicilie, vol. 1 (in Italian). Napoli: Stabilimento Migliaccio. p. 4.

- Thomson, D. W. (April 1995). "Prelude to the Sulphur War of 1840: The Neapolitan Perspective". European History Quarterly. 25 (2): 163–180. doi:10.1177/026569149502500201.

- Riall, Lucy (1998). Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy and Local Power, 1859–1866. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191542619. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- The Economist. Economist Newspaper Limited. 1975.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (12 October 2012). Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-134-60994-9.

- "La Dolce Vita? Italy By Rail, 1839-1914 | History Today". History Today. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Duggan, Christopher (1994). A Concise History of Italy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-40848-6.

- De Lucia, Maddalena; Ottaiano, Mena; Limoncelli, Bianca; Parlato, Luigi; Scala, Omar; Siviglia, Vittoria (2010). "The Museum of Vesuvius Observatory and its public. Years 2005 - 2008". EGUGA: 2942. Bibcode:2010EGUGA..12.2942D.

- Klemetti, Erik (7 June 2009). "Volcano Profile: Mt. Vesuvius". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- States, United (1931). Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America: Documents 173-200: 1855-1858. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 250.

Further reading

- Alio, Jacqueline. Sicilian Studies: A Guide and Syllabus for Educators (2018), 250 pp.

- Eckaus, Richard S. "The North-South differential in Italian economic development." Journal of Economic History (1961) 21#3 pp: 285–317.

- Finley, M. I., Denis Mack Smith and Christopher Duggan, A History of Sicily (1987) abridged one-volume version of 3-volume set of 1969)

- Imbruglia, Girolamo, ed. Naples in the eighteenth century: The birth and death of a nation state (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- Petrusewicz, Marta. "Before the Southern Question: 'Native' Ideas on Backwardness and Remedies in the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, 1815–1849." in Italy's 'Southern Question' (Oxford: Berg, 1998) pp: 27–50.

- Pinto, Carmine. "The 1860 disciplined Revolution. The Collapse of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies." Contemporanea (2013) 16#1 pp: 39–68.

- Riall, Lucy. Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy & Local Power, 1859–1866 (1998), 252pp

- Zamagni, Vera. The economic history of Italy 1860–1990 (Oxford University Press, 1993)

External links

- (in Italian) Brigantino – Il portale del Sud, a massive Italian-language site dedicated to the history, culture and arts of southern Italy

- (in Italian) Casa Editoriale Il Giglio, an Italian publisher that focuses on history, culture and the arts in the Two Sicilies

- (in Italian) La Voce di Megaride, a website by Marina Salvadore dedicated to Napoli and Southern Italy

- (in Italian) Associazione culturale "Amici di Angelo Manna", dedicated to the work of Angelo Manna, historian, poet and deputy

- (in Italian) Fora! The e-journal of Nicola Zitara, professor; includes many articles about southern Italy's culture and history

- Regalis, a website on Italian dynastic history, with sections on the House of the Two Sicilies

.jpg)