Albert I of Belgium

Albert I (Dutch: Albert Leopold Clemens Maria Meinrad; French: Albert Léopold Clément Marie Meinrad; German: Albert Leopold Clemens Maria Meinrad; 8 April 1875 – 17 February 1934) reigned as King of the Belgians from 1909 to 1934. He ruled during an eventful period in the history of Belgium, which included the period of World War I (1914–1918), when 90 percent of Belgium was overrun, occupied, and ruled by the German Empire. Other crucial issues included the adoption of the Treaty of Versailles, the ruling of the Belgian Congo as an overseas possession of the Kingdom of Belgium along with the League of Nations mandate of Ruanda-Urundi, the reconstruction of Belgium following the war, and the first five years of the Great Depression (1929–1934). King Albert died in a mountaineering accident in eastern Belgium in 1934, at the age of 58, and he was succeeded by his son Leopold III (r. 1934–1951).

| Albert I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Albert I, pictured with his characteristic Adrian helmet, c.1919 | |||||

| King of the Belgians | |||||

| Reign | 23 December 1909 – 17 February 1934 | ||||

| Predecessor | Leopold II | ||||

| Successor | Leopold III | ||||

| Prime Ministers | See list

| ||||

| Born | 8 April 1875 Brussels, Belgium | ||||

| Died | 17 February 1934 (aged 58) Marche-les-Dames, Namur, Belgium | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Leopold III of Belgium Prince Charles, Count of Flanders Marie-José, Queen of Italy | ||||

| |||||

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (until 1920) Belgium (from 1920) | ||||

| Father | Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders | ||||

| Mother | Princess Marie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Early life

|

| Leopold I |

|---|

|

Children

Grandchildren

|

| Leopold II |

| Albert I |

|

Children

|

| Leopold III |

|

Children

|

| Baudouin |

| Albert II |

|

Children

Grandchildren

|

| Philippe |

Albert Léopold Clément Marie Meinrad was born in Brussels, the fifth child and second son of Prince Philippe, Count of Flanders, and his wife, Princess Marie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Prince Philippe was the third (second surviving) son of Leopold I (r. 1831–1865), the first King of the Belgians, and his wife, Louise-Marie of France, and the younger brother of King Leopold II of Belgium (r. 1865–1909). Princess Marie was a relative of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany (r. 1888–1918), and a member of the non-reigning, Catholic branch of the Hohenzollern family. Albert grew up in the Palace of the Count of Flanders, initially as third in the line of succession to the Belgian throne as his reigning uncle Leopold II's son had already died. When, however, Albert's older brother, Prince Baudouin of Belgium, who had been subsequently prepared for the throne, also died young, Albert, at the age of 16, unexpectedly became second in line (after his father) to the Belgian Crown.

Retiring and studious, Albert prepared himself strenuously for the task of kingship. In his youth, Albert was seriously concerned with the situation of the working classes in Belgium, and personally travelled around working class districts incognito, to observe the living conditions of the people.[1] Shortly before his accession to the throne in 1909, Albert undertook an extensive tour of the Belgian Congo, which had been annexed by Belgium in 1908 (after having been previously owned by King Leopold II of Belgium as his personal property), finding the country in poor condition. Upon his return to Belgium, he recommended reforms to protect the native population and to further technological progress in the colony.[2]

Marriage

Albert was married in Munich on 2 October 1900 to Bavarian Duchess Elisabeth Gabrielle Valérie Marie, a Wittelsbach princess whom he had met at a family funeral. A daughter of Bavarian Duke Karl-Theodor, and his second wife, the Infanta Maria Josepha of Portugal, she was born at Possenhofen Castle, Bavaria, Germany, on 25 July 1876, and died on 23 November 1965.

The civil wedding was conducted by Friedrich Krafft Graf von Crailsheim in the Throne Hall,[3] and the religious wedding was conducted by Cardinal von Stein, assisted by Jakob von Türk, Confessionar of the King of Bavaria.[3]

Based on the letters written during their engagement and marriage (cited extensively in the memoirs of their daughter, Marie-José) the young couple appear to have been deeply in love. The letters express a deep mutual affection based on a rare affinity of spirit.[4] They also make clear that Albert and Elisabeth continually supported and encouraged each other in their challenging roles as king and queen. The spouses shared an intense commitment to their country and family and a keen interest in human progress of all kinds. Together, they cultivated the friendship of prominent scientists, artists, mathematicians, musicians, and philosophers, turning their court at Laeken into a kind of cultural salon.[4][5]

Children

Albert and Elisabeth had three children:

- Léopold Philippe Charles Albert Meinrad Hubert Marie Miguel, Duke of Brabant, Prince of Belgium, who became later the fourth king of the Belgians as Leopold III (3 November 1901 – 25 September 1983, at Woluwe-Saint-Lambert).

- Charles Théodore Henri Antoine Meinrad, Count of Flanders, Prince of Belgium, Prince Regent of Belgium (10 October 1903, in Brussels – 1 June 1983, at Ostend).

- Marie-José Charlotte Sophie Amélie Henriette Gabrielle, Princess of Belgium (4 August 1906, in Ostend – 27 January 2001). She was married at Rome, Italy on 8 January 1930 to Prince Umberto Nicola Tommaso Giovanni Maria, Prince of Piemonte (born 15 September 1904 and died on 18 March 1983 at Geneva, Switzerland). He became King Umberto II (r. 1946) of Italy.

Accession

Following the death of his uncle, Leopold II, Albert succeeded to the Belgian throne in December 1909, since Albert's own father had already died in 1905. Previous Belgian kings had taken the royal accession oath only in French; Albert innovated by taking it in Flemish as well.[1] He and his wife, Queen Elisabeth, were popular in Belgium due to their simple, unassuming lifestyle and their harmonious family life, which stood in marked contrast to the aloof, autocratic manner and the irregular private life of Leopold II. An important aspect of the early years of Albert's reign was his institution of many reforms in the administration of the Belgian Congo, Belgium's only colonial possession.[6]

Religion

King Albert was a devout Catholic.[4][7][8] Many stories illustrate his deep and tender piety. For instance, when his former tutor General De Grunne, in his old age, entered the Benedictine monastery of Maredsous in Belgium, King Albert wrote a letter to him in which he spoke of the joy of giving oneself to God.[7] He said: "May you spend many years at Maredsous in the supreme comfort of soul that is given to natures touched by grace, by faith in God's infinite power and confidence in His goodness."[8] To another friend, a Chinese diplomat who became a Catholic monk, Albert wrote: "Consecrating oneself wholly to the service of Our Lord gives, to those touched by grace, the peace of soul which is the supreme happiness here below."[8] Albert used to tell his children: "As you nourish your body, so you should nourish your soul."[4] In an interesting meditation on what he viewed as the harm that would result if Christian ideals were abandoned in Belgium, he said: "Every time society has distanced itself from the Gospel, which preached humility, fraternity, and peace, the people have been unhappy, because the pagan civilisation of ancient Rome, which they wanted to replace it with, is based only on pride and the abuse of force" (Commemorative speech for the war dead of the Battle of the Yser, given by Dom Marie-Albert, Abbot of Orval Abbey, Belgium, in 1936).

World War I

.jpg)

At the start of World War I, Albert refused to comply with Germany's request for safe passage for its troops through Belgium in order to attack France, which the Germans alleged was about to advance into Belgium en route to attacking Germany in support of Russia. In fact, the French Government had told its army commander not to go into Belgium before a German invasion.[9] The German invasion brought Britain into the war as one of the guarantors of Belgian neutrality under the Treaty of 1839. King Albert, as prescribed by the Belgian constitution, took personal command of the Belgian Army, and held the Germans off long enough for Britain and France to prepare for the Battle of the Marne (6–9 September 1914). He led his army through the Siege of Antwerp (28 September – 10 October 1914) and the Battle of the Yser (16–31 October 1914), when the Belgian Army was driven back to a last, tiny strip of Belgian territory near the North Sea. Here the Belgians, in collaboration with the armies of the Triple Entente, took up a war of position, in the trenches behind the River Yser, remaining there for the next four years. During this period, King Albert fought alongside his troops and shared their dangers, while his wife, Queen Elisabeth, worked as a nurse at the front. During his time on the front, rumours spread on both sides of the lines that the German soldiers never fired upon him out of respect for him being the highest ranked commander in harm's way, while others feared risking punishment by the Kaiser himself, who was his cousin. The King also allowed his 12-year-old son, Prince Leopold, to enlist in the Belgian Army as a private and fight in the ranks.[2][6]

The war inflicted great suffering on Belgium, which was subjected to a harsh German occupation. The King, fearing the destructive results of the war for Belgium and Europe and appalled by the huge casualty rates, worked through secret diplomatic channels for a negotiated peace between Germany and the Entente based on the "no victors, no vanquished" concept. He considered that such a resolution to the conflict would best protect the interests of Belgium and the future peace and stability of Europe. Since, however, neither Germany nor the Entente were favourable to the idea, tending instead to seek total victory, Albert's attempts to further a negotiated peace were unsuccessful. At the end of the war, as commander of the Army Group Flanders, consisting of Belgian, British and French divisions, Albert led the final offensive of the war that liberated occupied Belgium. King Albert, Queen Elisabeth, and their children then re-entered Brussels to a hero's welcome.

Post-war years

Upon his return to Brussels, King Albert made a speech in which he outlined the reforms he desired to see implemented in Belgium, including universal suffrage and the establishment of a Flemish University in Ghent.

Trip to the United States

From 23 September through 13 November 1919, King Albert, Queen Elisabeth of Bavaria, and their son Prince Leopold made an official visit to the United States. During a visit of the historic Native American pueblo of Isleta Pueblo, New Mexico, King Albert decorated Father Anton Docher with Knight in the Order of Leopold II.[10] Docher offered the King a turquoise cross mounted in silver made by the Tiwas Indians.[11][12] Ten thousand people travelled to Isleta for this occasion. That same year he was elected an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati.

In New York the King received a ticker tape parade in his honour. The visit, which was prepared by his private secretary Max-Léo Gérard, was considered a success by the Belgian authorities.[3]

Introduction of universal male suffrage

Since the Belgian general strike of 1893, plural votes had been granted to individual men based on their wealth, education, and age,[13] but after the Belgian general strike of 1913 the promise had been made to have constitutional reform for one man, one vote universal suffrage but the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914 and the subsequent occupation delayed the implementation of the commission's proposal.

In 1918, King Albert forged a post-war "Government of National Union" made up of members of the three main parties in Belgium, the Catholics, the Liberals, and the Socialists[1][6] and attempted to mediate between the parties in order to bring about one man, one vote universal suffrage for men. He succeeded.[14]

Paris Peace Conference

The Belgian Government sent the King to the Paris Peace Conference in April 1919, where he met with the leaders of France, Britain and the United States. He had four strategic goals:

- to restore and expand the Belgian economy using cash reparations from Germany;

- to assure Belgium's security by the creation of a new buffer state on the left bank of the Rhine;

- to revise the obsolete treaty of 1839;

- to promote a 'rapprochement' between Belgium and the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg.

He strongly advised against a harsh, restrictive treaty against Germany to prevent future German aggression.[15] He also considered that the dethronement of the princes of Central Europe and, in particular, the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire would constitute a serious menace to peace and stability on the continent.[7] The Allies considered Belgium to be the chief victim of the war, and it aroused enormous popular sympathy, but the King's advice played a small role in Paris.[16]

Later years

Albert spent much of the remainder of his reign assisting in the post-war reconstruction of Belgium.

In 1920 Albert changed the family name from “Saxe-Coburg-Gotha” to “House of Belgium” (van België, in Dutch; de Belgique in French) as a result of strong anti-German sentiment.[17] This mirrored the British royal family's name-change to House of Windsor in 1917.[18]

Albert was a committed conservationist and in 1925, influenced by the ideas of Carl E. Akeley, he founded Africa's first national park, now known as Virunga National Park, in what is now Democratic Republic of Congo. During this period, he was also the first reigning European monarch to visit the United States.[19]

Death

A passionate alpinist, King Albert I died in a mountaineering accident while climbing alone on the Roche du Vieux Bon Dieu at Marche-les-Dames, in the Ardennes region of Belgium near Namur. His death shocked the world and he was deeply mourned, both in Belgium and abroad. Because King Albert was an expert climber, some questioned the official version of his death and suggested that the King was murdered (or even committed suicide) somewhere else and that his body had never been at Marche-les-Dames, or that it was deposited there.[20][21] Several of those hypotheses with criminal motives were already investigated by the juridical authorities but the doubts have been increased ever since, today still being the subject of popular novels, books and documentaries.[22] Nonetheless, rumors of murder have been dismissed by most historians. There are two possible explanations for his death according to the official juridical investigations: the first was he leaned against a boulder at the top of the mountain, which became dislodged; or two, the pinnacle to which his rope was belayed had broken, causing him to fall about sixty feet.[23] In 2016 DNA testing by geneticist Dr. Maarten Larmuseau and colleagues from the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven on bloodstained leaves collected from Marche-les-Dames concluded that King Albert died at that location.[24]

Like his predecessors Leopold I and Leopold II, King Albert is interred in the Royal Crypt at the Church of Our Lady of Laeken in Brussels.[25]

In 1935, prominent Belgian author Emile Cammaerts published a widely acclaimed biography of King Albert I, titled Albert of Belgium: Defender of Right. In 1993, a close climbing companion of the King, Walter Amstutz, founded the King Albert I Memorial Foundation, an association based in Switzerland and dedicated to honouring distinguished individuals in the mountaineering world.

To celebrate 175 years of Belgian Dynasty and the 100th anniversary of his accession,[26] Albert I was selected as the main motif of a high-value collectors' coin: the Belgian 12.5 euro Albert I commemorative coin, minted in 2008. The obverse shows a portrait of the King.[26]

Titles, styles, arms, and honours

Titles and styles

- 8 April 1875 – 23 December 1909: His Royal Highness Prince Albert of Belgium, Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Duke of Saxony

- 23 December 1909 – 17 February 1934: His Majesty The King of the Belgians

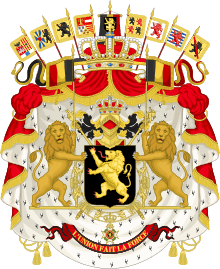

Arms

| Heraldry of Albert I of Belgium | ||

|---|---|---|

| On his birth, Albert was granted a coat of arms. These were those of the king, differenced by a label gules, with one crescent argent on the central point. When his father died in 1905, the crescent was removed. When he acceded as King, he gained the royal arms (Belgium with inescutcheon of the shield of Saxony), undifferenced. Finally, after the abolition of the monarchy in Germany and the subsequent loss of his Saxon titles, Albert had the inescutcheon removed in 1921. | ||

|

Monograms

|

|

|

|

Honours and awards

- National[27]

- He was Grand Master of the following chivalric orders:

- War Cross

- Commemorative Medal

- Yser Medal

- Foreign[27]

- Collar of the Order of Albania[29]

- Collar of the Order of Skanderbeg, in Diamonds and Rubies

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 1907[30]

- Grand Cross of St. Stephen, 1910[31]

- Knight of Saints Cyril and Methodius, with Collar[33]

- Grand Cross of St. Alexander

- China:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Collar of the White Lion, 1925[38]

- War Cross (1914–1918)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour[45]

- Médaille militaire

- Croix de guerre (1914–1918), with Palm leaves[45]

- (Algeria): Green Beetle of Tabelbala[46]

- (Cambodia): Grand Cross of the Order of Cambodia

- (Morocco):

- Grand Cordon of Ouissam Alaouite[47]

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Military Merit[47]

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Black Eagle[48]

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle[49]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

- Knight of the Annunciation, 1910

- Grand Cross of the Crown of Italy, 1910

- Grand Cross of the Military Order of Savoy

- War Merit Cross[55]

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, 1900 – wedding gift of the Patriarch of Jerusalem[56][52]

- Knight of the Supreme Order of Christ, 1934

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the White Eagle

- Grand Cross of the Virtuti Militari, 12 December 1923[65]

- Portugal:

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Sash of the Three Orders, 19 July 1919[67]

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword[68]

- Collar of the Order of Carol I, 1910[69]

- Order of Michael the Brave, 1st Class[70][71]

- Grand Cross of the Star of Romania[70]

- Order of the Aeronautical Virtue[71]

- Knight of St. Andrew

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky

- Knight of the White Eagle

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class

- Medal of the Order of St. George[72]

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Star of Karađorđe, with Swords[73][74]

- Grand Cross of the Cross of Takovo[75]

- Gold Medal for Bravery[73]

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Garter, 5 December 1914[78]

- Honorary Grand Cross of the Bath (military)[79][80]

- Bailiff Grand Cross of St. John, 12 June 1926[81]

- Distinguished Flying Cross[80][82][83]

- King Edward VII Coronation Medal[79]

.svg.png)

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Albert I of Belgium |

|---|

See also

- Kings of Belgium family tree

- Crown Council of Belgium

- Royal Trust

References

- Carlo Bronne. Albert 1er: le roi sans terre.

- Evelyn Graham. Albert, King of the Belgians.

- Albert I;Museum Dynasticum N° .21: 2009/ n° 2.

- Luciano Regolo. La regina incompresa: tutto il racconto della vita di Maria José di Savoia.

- Marie-José, Queen, Consort of Umberto II, King of Italy. Albert et Elisabeth de Belgique, mes parents.

- Roger Keyes. Outrageous Fortune: The Tragedy of Leopold III of the Belgians.

- Charles d'Ydewalle. Albert and the Belgians: Portrait of a King.

- Jo Gérard. Albert 1er, insolite: 1934–1984.

- Margaret MacMillan: The War that Ended the Peace (2013)p.585

- Keleher and Chant. The Padre of Isleta. Sunstone Press, 2009, p. 94.

- W. A. Keleher. The Indian sentinel. 1920, vol. 2. pp. 23–24

- Samuel Gance, Anton ou la trajectoire d'un père, L'Harmattan, 2013, p.174.

- Els Witte, Jan Craeybeckx, Alain Meynen Political History of Belgium: From 1830 Onwards, Academic and Scientific Publishers, Brussels, 2009, p. 278. ISBN 978-90-5487-517-8

- Charles d'Ydewalle, Albert and the Belgians: Portrait of a King, Translated from the French, by Phyllis Megroz, London, 1935, p. 198 and the following pages.

- Vincent Dujardin, Mark van den Wijngaert, et al. Léopold III

- Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919 (2003) pp. 106, 272

- "The Belgian monarchy" (PDF). Belgium. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- "House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha". Scribd. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- William Mark Adams (2004). Against Extinction: The Story of Conservation. Earthscan. p. 5.

- NOTERMAN, Jacques (2004). Le roi tué. Brussels: Editions Jourdan le Clercq. ISBN 9782930359069.

- Raskin, Evrard (2005). Elisabeth Van België - Een ongewone koningin. Antwerp: Hautekiet. ISBN 905240822X.

- Van Ypersele, Laurence (2006). Le roi Albert: Histoire d'un mythe. Charleroi: Broché. ISBN 978-2804021764.

- Donaldson, Norman and Betty (1980). How Did They Die?. Greenwich House. ISBN 0-517-40302-1.

- New Historian, 24 July 2016Archived 25 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- "Koninklijke Crypte van Laken". Monarchie (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 11 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- "Belgium commemorative euro coins – 2008". Euro Master – Online Euro Catalog. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- http://www.ars-moriendi.be/ALBERT_I.HTM">

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Afghanistan, Ordre d'Ustar

- "Albanian Royal Family – Royal Decorations and Warrents". www.albanianroyalcourt.al. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Boettger, T. F. "Chevaliers de la Toisón d'Or - Knights of the Golden Fleece". La Confrérie Amicale. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Bolivia, Ordre du Condor des Andes – Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Knights of the Order of Saints Cyril and Methodius". Official Site of King Simeon II (in Bulgarian). Sofia. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Chile, Ordre Al Merito Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – World Medals Index, Chile: Order of Merit Archived 21 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- L'Indépendance belge, 9 May 1914, p. 2

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Colombia, Ordre de Boyaca

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Cuba, Ordre du Mérité "Carlos Manuel de Cespedes" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kolana Řádu Bílého lva aneb hlavy států v řetězech" (in Czech), Czech Medals and Orders Society. Retrieved 2018-08-09.

- Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 463. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Ecuador, Ordre Al Merito Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – World Medals Index, Ecuador: National Order of Merit Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Egypt, Ribbon bar Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Ethiopia, Ordre du Sceau de Salomon Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Ribbon bar

- "Cross of Liberty: Albert I of Belgium". Estonian State Decorations (in Estonian). Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Suomen Valkoisen Ruusun Suurristi Ketjuineen". ritarikunnat.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, France, Ordre de la Légion d'Honneur Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Médaille militaire Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Croix de Guerre Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Ribbon bars of the 3 orders

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, France (Algeria), Scarabée vert de Tabelbala Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Morocco, Ordre Ouissam Alaouite Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (Ribbon bar) – Ordre du Mérite Chérifien Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1923) p. 20

- The titled nobility of Europe. London: Harrison and Sons. 1914. pp. 30–33.

- A. Manceaux, Imprimeur-Libraire, ed. (1905). Almanach de poche de Bruxelles et de ses faubourgs (in French). Brussels. p. 9.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1910), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 41

- Nieuws Van Den Dag (Het) 02-10-1900

- Staatshandbücher für das Herzogtum Sachsen-Meiningen (1912), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 23

- Journal de Bruxelles 14-04-1910

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Italy, Croix du Mérite de Guerre – Ribbon bar

- Handelsblad (Het) 09-10-1900

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Japan, Ordre Suprême du Chrisanthème – Ribbon bar

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Lithuania, Ordre de Vytis Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Luxembourg, Ordre du Lion de la Maison de Nassau Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Monaco, Ordre de Saint Charles Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Netherlands, Ordre du Lion Néerlandais – Ribbon bar Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Norway, Ordre de Saint-Olaf Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Persia, Ordre de la Couronne de Perse – Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Peru, Ribbon bar Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Stanisław Łoza (1935), "Virtuti Militari", Broń i Barwa” (in Polish), Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Przyjaciół Muzeum Wojska, p. 148

- Bragança, Jose Vicente de (2014). "Agraciamentos Portugueses Aos Príncipes da Casa Saxe-Coburgo-Gota" [Portuguese Honours awarded to Princes of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 9–10: 11. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Banda da Grã-Cruz das Três Ordens - Alberto I (Rei da Bélgica)" (in Portuguese), Arquivo Histórico da Presidência da República. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Portugal, Ordre de la Tour et de l'Epée Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Ordinul Carol I" [Order of Carol I]. Familia Regală a României (in Romanian). Bucharest. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Romania, Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Romania, Ordre Militaire de Michel le Brave – Croix du Mérite Aéronautique

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Russian Empire, Ordre Militaire de Saint Georges Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Serbia, Ordre de Karageorge avec Glaives Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Médaille d'Or pour le Bravoure

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 144.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 364.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guóa Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1930, p. 220, retrieved 4 March 2019

- Sveriges statskalender (in Swedish), 1915, p. 671, retrieved 20 February 2019 – via runeberg.org

- "Knights of the Garter created during the reign of King George V (1910–1936)" Archived 7 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Cracroft's Peerage: The Complete Guide to the British Peerage & Baronetage. Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, United Kingdom, ] "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) – DFC – Méd. du Couronnement d'Édouard VII

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, United Kingdom, Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "No. 33284". The London Gazette. 14 June 1927. p. 3836.

- P E Abbott & J M A Tamplin. British Gallantry Awards. p. 96. Nimrod Dix & Co, London, 1981.ISBN 0-902633-74-0

- UK National Archives: AIR 2/207/101335/21

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, United States, Distinguished Service Medal Archived 5 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Belgian Army Royal Museum, Decorations of King Albert I, Venezuela, Ordre du Buste du Libérateur Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Ribbon bar Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Galet, Emile Joseph. Albert King of the Belgians in the Great War (1931), detailed memoir by the military advisor to the King; covers 1912 to the end of October 1914

- Woodward, David. "King Albert in World War I" History Today (1975) 25#9 pp. 638–43

- D'Ydewalle, Charles. "Albert King of the Belgians"(1935) Translated by Phyllis Megroz D'Ydewalle a journalist describes his book in the foreword.."This book is not a history, it is a sheaf of memories" The final chapter contains interviews with the people who discovered the king's body after his climbing accident

- Catherine Barjansky. Portraits with Backgrounds.

- Mary Elizabeth Thomas, "Anglo-Belgian Military Relations and the Congo Question, 1911–1913", Journal of Modern History, Vol. 25, No. 2 (June 1953), pp. 157–165.

- Page, Walter Hines; Page, Arthur Wilson (January 1915). "The Well-Beloved King of The Belgians". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XXIX: 280–288. Retrieved 4 August 2009.

- De Spiegeleer, Christoph (2015). "Royal Losses, Symbolic Politics and Media Events in Interwar Europe: Responses to the Accidental Deaths of King Albert I and Queen Astrid of Belgium (1934–1935)". Contemporary European History. 24 (2): 155–174.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Albert I of Belgium. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1922 Encyclopædia Britannica article "Albert I.". |

- Official biography from the Belgian Royal Family website

- Funeral of King Albert of The Belgians, newsreel on the British Movietone YouTube Channel

- Information about King Albert's mountaineering feats

- Belgium in the First World War, including stories of the royal couple, in French

- Archive Albert I of Belgium, Royal museum of central Africa

- Newspaper clippings about Albert I of Belgium in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Portraits of Albert I of Belgium at the National Portrait Gallery, London

| Royal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Leopold II |

King of the Belgians 1909–1934 |

Succeeded by Leopold III |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)