La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana, (Spanish: The House of Charity and Maternity of Havana) was for 270 years Havana's repository of Havana's unwanted children. The House of Charity started during a time when Cuba was experiencing extreme poverty, unemployment, and corruption in the government. Corrupt leaders were plundering the public treasury and little attention was given to social assistance, health, education, or the protection of the poor: "los desamparados".

| La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana | |

|---|---|

View from San Lazaro | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Religious charity |

| Architectural style | Neo-classical |

| Location | Cayo Hueso |

| Address | San Lazaro y Belascoáin |

| Town or city | |

| Country | Cuba |

| Coordinates | 23°08′26.5″N 82°22′16.3″W |

| Named for | La Casa Cuna |

| Construction started | 1794 |

| Demolished | 1959[1] |

| Height | 16.74 meters (54.9 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Load bearing |

| Material | Masonry, wood |

| Floor count | 2 |

| Grounds | 360,000 square feet (33,000 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Francisco Vambitelli[1] |

Corruption

Cuba had suffered from widespread and rampant corruption since the establishment of the Republic in 1902. The book Corruption in Cuba states that public ownership resulted in "a lack of identifiable ownership and widespread misuse and theft of state resources... when given opportunity, few citizens hesitate to steal from the government."[2] Furthermore, the complex relationship between governmental and economic institutions makes them especially "prone to corruption."[3]

Brothels flourished. A major industry grew up around them; government officials received bribes, policemen collected protection money. Prostitutes could be seen standing in doorways, strolling the streets, or leaning from windows. One report estimated that 11,500 of them worked their trade in Havana. Beyond the outskirts of the capital, beyond the slot machines, was one of the poorest, and most beautiful countries in the Western world.

— David Detzer, American journalist, after visiting Havana in the 1950s [4]

The question of what causes corruption in Cuba presently and historically continues to be discussed and debated by scholars. Jules R. Benjamin suggests that Cuba's corrupt politics were a product of the colonial heritage of Cuban politics and the financial aid provided by the United States that favoured international sugar prices in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[5] Following the Second World War, the level of corruption in Cuba, among many other Latin American and Caribbean countries, was said to have risen significantly.[6] Some scholars, such as Eduardo Sáenz Rovner, attribute this to North America's increased involvement in Cuba after the First World War as it isolated Cuban workers.[6] Cubans were excluded from a large sector of the economy and unable to participate in managerial roles that were taken over by United States employers.[6] Along similar lines, Louis A. Pérez has written that “World War Two created new opportunities for Cuban economic development, few of which, however, were fully realized. Funds were used irrationally. Corruption and graft increased and contributed in no small part to missed opportunities, but so did mismanagement and miscalculation.”[7]

History

The Real Casa de Maternidad y Beneficencia emerged as a product of several transitions between "La Casa Cuna," the "Real Casa de Maternidad", and finally "La Casa de Beneficencia." It was not until 1794 during the government of Luis de las Casas that the Beneficencia was located in its final location in Barrio San Lazaro at the corners of San Lazaro and Belascoáin.

The Casa Cuna was founded in 1687 by Bishop Diego Evelino Hurtado de Compostela. His death left the orphanage unfinished due to lack of resources to carry out his efforts.[8] His successor, Bishop Fray Gerónimo de Nosti y Valdés, took up his idea and restored the Casa Cuna in a building he built on the corner of Oficios and Muralla.[9] It originally housed two hundred orphans.[10]

In the year 1792, Don Luis de Peñalver, on the initiative of the Countess of Jaruco, the Marquises of Cárdenas de Monte Hermoso, the Marquis of Casa Peñalver and the Bishop of the Provinces of Louisiana and Florida, founded the "Real Casa de Beneficencia." It accepted only females, settling in a cavalry room of land located in front of the San Lázaro cove, which was an area known as the Betancourt Garden that the Bishop of Peñalver gave for this purpose. They offered to contribute 36 thousand pesos, requesting the governor to manage the royal approval and suggest the land in front of the Caleta de San Lázaro with a view to the sea and running waters.

Antonia María Menocal, a lady of Havana, left at the time of her death in 1830 a large legacy to be invested in charitable works. The executor assigned it to the creation of a Maternity House and for the preservation and education of children up to the age of six.[10][11]

Marcial Dupierris in 1857 wrote: "The Real Casa de Beneficencia, which is also in the neighborhood of San Lazaro, is a large building, whose front faces the street Wide North, its side E. is on the road of Belascoaín, and extends to the S to face with the house of health of San Leopoldo, said Real establishment, is the refuge of the orphans of both secured [sic]. He is educated and supported until the age when he allows them to be applied to any kind of work. In one of the departments of their dependency there are the insane; in another the Cradle house—that is, in the spitting room. [sic] Those different departments are entrusted to the care of people who enjoy the best reputation. Of getting married, they receive a dowry of five hundred pesos that the house gives them, and when they are placed for the service of private homes, it is with the preceding report and recommendation of good reputation and morality of the people to whose care they are delivered."[12]

La Casa de Maternidad was added to the Beneficiencia on the initiative of Spanish Governor Manuel Gutiérrez de la Concha, who administered the island from 1850 to 1852. La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad was administered by the Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País.

In 1914, the State assumed the institution which continued to survive on the alms and the service of the Daughters of Charity of Cuba.

The Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital, the largest health facility in the country, was built in place of the former La Casa de Beneficencia.[9][10]

Tradition

Children who had no last name were given the surname Valdés upon entering the charity. The name derived from Bishop Fray Gerónimo de Nosti y Valdés, successor of Diego Evelino Hurtado de Compostela.[9][10] Bishop Fray Gerónimo de Nosti y Valdés is buried at Iglesia del Espíritu Santo, Havana in La Habana Vieja.

Mothers who abandoned their children for economic reasons or for the shame of being a single mother, could deliver them without showing their face or revealing their identity.[lower-alpha 1] Ciro Bianchi Ross wrote: "For that, in the side façade of the building that faced the Belascoaín Road, there was the lathe; the infant was placed in it and the deposit was turned at the touch of a bell, and on the other side the abandoned child received a nun from the Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, a congregation that served that semi-private institution that tried to supply the official lack of attention in its attempt to redeem evils that the State did not suppress or remedy..."[1] The nuns were of the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paulo (Hermanas de la Caridad de San Vicente de Paulo), the congregation that served La Casa de Beneficencia.

Baby hatch

Baby hatches have existed in one form or another for centuries. The system was quite common in medieval times. From 1198 the first foundling wheels (ruota dei trovatelli) were used in Italy; Pope Innocent III decreed that these should be installed in homes for foundlings so that women could leave their child in secret instead of killing them, a practice clearly evident from the numerous drowned infants found in the Tiber River. A foundling wheel was a cylinder set upright in the outside wall of the building, rather like a revolving door. Mothers placed the child in the cylinder, turned it around so that the baby was inside the church, and then rang a bell to alert caretakers. One example of this type which can still be seen today is in the Santo Spirito hospital at the Vatican City; this wheel was installed in medieval times and used until the 19th century.

In Hamburg, Germany, a Dutch merchant set up a wheel (Drehladen) in an orphanage in 1709. It closed after only five years in 1714 as the number of babies left there was too high for the orphanage to cope with financially. Other wheels are known to have existed in Kassel (1764) and Mainz (1811).

In France, foundling wheels (tours d'abandon, abandonment wheel) were introduced by Saint Vincent de Paul who built the first foundling home in 1638 in Paris. Foundling wheels were legalised in an imperial decree of January 19, 1811, and at their height, there were 251 in France, according to author Anne Martin-Fugier. They were in hospitals such as the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés (Hospital for Foundling Children) in Paris. However, the number of children left there rose into the tens of thousands per year, as a result of the desperate economic situation at the time, and in 1863 they were closed down and replaced by "admissions offices" where mothers could give up their child anonymously but could also receive advice. The tours d'abandon were officially abolished in law of June 27, 1904. Today in France, women are allowed to give birth anonymously in hospitals (accouchement sous X) and leave their baby there.

In Brazil and Portugal, foundling wheels (roda dos expostos/enjeitados, literally "wheel for exposed/rejected ones") were also used after Queen Maria I proclaimed on May 24, 1783, that all towns should have a foundling hospital. One example was the wheel installed at the Santa Casa de Misericordia hospital in São Paulo on July 2, 1825. This was taken out of use on June 5, 1949, declared incompatible with the modern social system after five years' debate. A Brazilian film on this subject, Roda Dos Expostos, directed by Maria Emília de Azevedo, won an award for "Best Photography" at the Festival de Gramado in 2001.

In Britain and Ireland, foundlings were brought up in orphanages financed by the Poor Tax. The home for foundlings in London was established in 1741; in Dublin the Foundling Hospital and Workhouse installed a foundling wheel in 1730, as this excerpt from the Minute Book of the Court of Governors of that year shows:

- "Hu (Boulter) Armach, Primate of All-Ireland, being in the chair, ordered that a turning-wheel, or convenience for taking in children, be provided near the gate of the workhouse; that at any time, by day or by night, a child may be layd in it, to be taken in by the officers of the said house."[13]

The foundling wheel in Dublin was taken out of use in 1826 when the Dublin hospital was closed because of the high death rate of children there.

Building

The building commanded certain moral and strategic positions in its philanthropic and charitable mission of providing aid to unwanted children, and in its geographic location as the first building of the first new city lot in the Barrio de San Lázaro. The Casa de Beneficencia eventually reached from Calles San Lazaro and Belascoáin to Marquez Gonzalez and Virtudes where the Jai alai fronton was located. "Beneficencia had two gates, the front that overlooked San Lázaro street with a large garden. The right part of that building (facing north), corresponded to the chapel that was always open to the public. To the left of the main entrance were the school offices followed by the barbershop and other workshops. The students were never in those gardens where there was only the possibility of visual contact with them. The other gate that served as access to the vehicles only, was in the back of the school, that is, in Virtudes street between Belascoaín and Lucena. On the right (always facing north), part of the building was located dedicated to the classrooms and on its left was the hospital. This school was converted into a barracks...they took us out of there to turn it into the Antonio Maceo military school."[1]

The Casa de Beneficencia eventually reached from Calles San Lazaro and Belascoáin to Marquez Gonzalez and Virtudes where the jai alai fronton was located.[14] A former orphan described the place:

"(the) Beneficencia had two gates; the front that overlooked San Lázaro street with a large garden. The right part of that building (facing north), corresponded to the chapel that was always open to the public. To the left of the main entrance were the school offices followed by the barber shop and other workshops. The students were never in those gardens where there was only the possibility of a visual contact with them. The other gate that served as access to the vehicles only was in the back of the school; that is, on Virtudes Street between Belascoaín and Lucena. On the right (always facing north), part of the building was located dedicated to the classrooms and on its left was the hospital... This magnificent school was converted into a barracks... they took us out of there to turn it into the Antonio Maceo military school."[1]

Legacy

La Casa de Beneficencia inspired the protagonist of Cecilia Valdés, written by Cirilo Villaverde. Cecilia Valdés is also the protagonist of Reinaldo Arenas's La Loma del Angel.[15][16] Real characters that flourished from La Casa de Beneficencia were: the poet Gabriel de la Concepcion Valdés (Plácido), the priest Fray José Olallo Valdés, and the doctor Juan Bautista Valdés, among others.[9]

Notes

- "… For that, on the side of the building that faces Calle Belascoaín, there was the lathe. The infant was placed in it and the tank turned at the touch of a bell. On the other side I received the abandoned child a nun from the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul, a congregation that attended that semi-private institution that tried to replace the official incuria in its attempt to redeem evils that the State did not suppress or remedy ... ".[1]

References

- "LA CASA DE BENEFICENCIA Y MATERNIDAD DE LA HABANA". Retrieved 2018-12-02.

- Sergio., Diaz-Briquets (2006). Corruption in Cuba : Castro and beyond. Pérez-López, Jorge F. (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292714823. OCLC 64098477.

- Political corruption : concepts & contexts. Heidenheimer, Arnold J., Johnston, Michael, 1949- (3rd ed.). New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. 2002. ISBN 978-0765807618. OCLC 47738358.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The Brink: Cuban Missile Crisis 1962, by David Detzer, Crowell, 1979, ISBN 0690016824, p. 17.

- R., Benjamin, Jules (1990). The United States and the origins of the Cuban Revolution : an empire of liberty in an age of national liberation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691025360. OCLC 19811341.

- Eduardo., Sáenz Rovner (2008). The Cuban connection : drug trafficking, smuggling, and gambling in Cuba from the 1920s to the Revolution. Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0807831755. OCLC 401386259.

- 1943-, Pérez, Louis A. (2003). Cuba and the United States : ties of singular intimacy (Third ed.). Athens, Ga.: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820324838. OCLC 707926335.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "LA REAL CASA CUNA DE LA HABANA". Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- "La Real Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad". Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- "Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad". Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- "Anales de la Academia de Ciencias Medicas, Fïsicas y ..., Volumes 40-41". Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- "Cayo Hueso: Con la vista fija en un lugar de Centro Habana". Retrieved 2018-11-28.

- "First Hospital in Dublin - Poor Relief in former days - The Foundling Hospital and its Founders". Archived from the original on 2006-05-01. Retrieved 2006-05-01.

- Arenas, Reinaldo. La Loma del Angel. US, 1987. ISBN 978-0-380-75075-7

- Rosell, Sara. “‘Cecilia Valdés’ De Villaverde a Arenas: La (Re)Creación Del Mito De La Mulata.”Afro-Hispanic Review, vol. 18, no. 2, 1999, pp. 15–21. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41826908.

Gallery

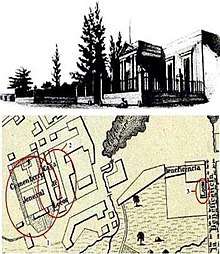

Map of 1900 showing Hospital de San Lazaro, Espada Cemetery, La Casa de Beneficencia, the Bateria de la Reina, the canteras, and the Caleta de S. Lazaro

Map of 1900 showing Hospital de San Lazaro, Espada Cemetery, La Casa de Beneficencia, the Bateria de la Reina, the canteras, and the Caleta de S. Lazaro 1855 map showing location of hospital of San Dionisio, La Casa de Beneficencia y File:Maternidad de La Habana, and the Espada Cemetery

1855 map showing location of hospital of San Dionisio, La Casa de Beneficencia y File:Maternidad de La Habana, and the Espada Cemetery La Casa de Beneficencia during the cyclone of 1919 with the statute of Antonio Maceo in the background.

La Casa de Beneficencia during the cyclone of 1919 with the statute of Antonio Maceo in the background. Café Vista Alegre. San Lazaro y Belascoáin. Shows front lawn of Casa de Beneficencia. ca 1900

Café Vista Alegre. San Lazaro y Belascoáin. Shows front lawn of Casa de Beneficencia. ca 1900 View from San Lazaro and Belascoáin.

View from San Lazaro and Belascoáin. La Casa de Beneficencia from Calle San Lazaro

La Casa de Beneficencia from Calle San Lazaro La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana from Belascoáin y Malecon 1940s

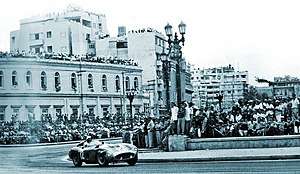

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana from Belascoáin y Malecon 1940s La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana. Cuban Grand Prix. 1957

La Casa de Beneficencia y Maternidad de La Habana. Cuban Grand Prix. 1957