Interstate 66

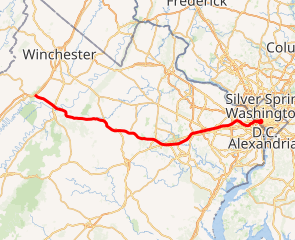

Interstate 66 (I-66) is an Interstate Highway in the eastern United States. As indicated by its even route number, it runs in an east–west direction. Its western terminus is near Middletown, Virginia, at an interchange with I-81;[3] its eastern terminus is in Washington, D.C., at an interchange with U.S. Route 29.[4] Because of its terminus in the Shenandoah Valley, the highway was once called the "Shenandoah Freeway."[5] Much of the route parallels U.S. Route 29 or Virginia State Route 55. Interstate 66 has no physical or historical connection to the famous U.S. Route 66 which was in a different region of the United States.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I-66 highlighted in red | |||||||

| Route information | |||||||

| Length | 76.38 mi[1] (122.92 km) | ||||||

| Existed | 1961[2]–present | ||||||

| Restrictions | No trucks on Custis Memorial Parkway or Theodore Roosevelt Bridge | ||||||

| Major junctions | |||||||

| West end | |||||||

| |||||||

| East end | |||||||

| Location | |||||||

| States | Virginia, District of Columbia | ||||||

| Counties | VA: Frederick, Warren, Fauquier, Prince William, Fairfax, Arlington DC: District of Columbia | ||||||

| Highway system | |||||||

| |||||||

The E Street Expressway is a spur from Interstate 66 into the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Route description

_in_Warren_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

| mi | km | |

|---|---|---|

| VA | 74.8 | 120.54 |

| DC | 1.6 | 2.57 |

| Total | 76.4 | 123.11 |

Virginia

_in_Reliance%2C_Warren_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

Because I-66 is the only Interstate Highway traveling west from Washington, D.C., into Northern Virginia, traffic on the road is often extremely heavy. For decades, there has been talk of widening I-66 from 2 to 3 lanes each way inside the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495) through Arlington County, Virginia, although many Arlington residents are adamantly opposed to this plan.

In 2005, the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) studied the prospect of implementing a one-lane-plus-shoulder extension on westbound I-66 within the Beltway (in an attempt to reduce congestion for people commuting away from D.C.).[6]

In the summer of 2010, construction began on a third lane and a 12-foot shoulder lane on westbound I-66 between the highway's Fairfax Drive entrance ramp (a short distance west of George Mason Drive near Ballston) and its Sycamore Street exit ramp, a 1.9 mile distance. The entrance ramp acceleration lane and the exit ramp deceleration lanes were lengthened to form a continuous lane between both ramps. The 12-foot shoulder lane can carry emergency vehicles and can be used in emergency situations. This project was completed in December 2011.[7]

The Orange Line and the Silver Line of the Washington Metro operate in the median of the highway in Fairfax and Arlington counties. Four stations (Vienna, Dunn Loring, West Falls Church, and East Falls Church) are located along this segment of I-66.

I-66 east has two exit ramps, one from each side of the highway, to the Inner Loop of I-495 heading northbound. One is a two lane right exit which merges down to one lane halfway along the ramp, while a second exit ramp is a left exit; the latter reserved for use by high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) traffic during morning rush hour, but open to all traffic excluding trucks at all other times. Both exit ramps for the Inner Loop merge prior to merging from the left with the Inner Loop. There is no access from the Outer Loop of I-495 to I-66 east; traffic wishing to make this movement must use State Route 267 east.

I-66 east also has two exits, one from each side of the highway, to the Outer Loop of I-495. One is a right exit, while one is a left exit; the latter shares a ramp with the exit to the Inner Loop of I-495.

I-66 is named the "Custis Memorial Parkway" east of the Capital Beltway in Virginia.[8] The name commemorates the Custis family, several of whose members (including Martha Dandridge Custis Washington, George Washington Parke Custis, Eleanor (Nellie) Parke Custis Lewis and Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee) played prominent roles in Northern Virginia's history.

HOV designation and rules

Due to heavy commuter traffic, I-66 features a variety of high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) restrictions. Between US 15 in Haymarket, Virginia and the Capital Beltway, the left lane on eastbound I-66 is reserved for vehicles with two or more occupants (HOV-2 traffic) from 5:30 to 9:30 a.m. on weekdays, and the left lane on westbound I-66 is reserved for HOV-2 traffic from 3:00 to 7:00 p.m on weekdays.

Between the Beltway and the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge, the eastbound (inbound) roadway is a HOT road from 5:30 to 9:30 a.m., and the westbound (outbound) roadway is a HOT road from 3:00 to 7:00 p.m. E-ZPass is required for all vehicles except motorcycles, including Dulles Airport users. I-66 is free during those times for HOV-2 drivers (HOV-3 in 2022) with an E-ZPass Flex and for motorcycles. Other drivers must pay a toll which can be almost $50 at peak times.[9]

_in_Oakton%2C_Fairfax_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

Inside and outside the Beltway improvement projects

The Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) Transportation planning board has added I-66 HOT lanes to their list of priority projects for the I-66 corridor.[10] The projects have sparked opposition between residents and community businesses over the direction of this region's future infrastructure planning.

The VDOT established a "Transform 66" website on regional traffic issues. Residents living within the I-66 corridor have set up "Transform 66 Wisely", a website describing local community impacts that the VDOT projects may cause. In contrast, local business groups and Chambers of Commerce located near the affected areas have voiced support for transportation improvements in the I-66 region.[11]

Residents along the I-66 corridor such as Arlington County have resisted I-66 widening proposals for many years.[12] The local Stenwood Elementary School would lose its attached field, leaving it with blacktop-only recess space.[13] In an April 16, 2015, letter to the Virginia Secretary of Transportation, members of the 1st, 8th, 10th, and 11th districts of Congress wrote that VDOT research noted that during peak hours, 35% of eastbound cars and 50% of westbound cars are HOV violators.

Future federal steps for VDOT include NEPA review, obligation of federal funds, certification that the conversion to tolled facilities will not "degrade" the existing facility, and potential federal loan guarantee. The Virginia Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) is responsible for overseeing VDOT and allocating highway funding to specific projects. The board has 18 members appointed by the Governor [14] and includes the Virginia Secretary of Transportation, Aubrey Layne, and is the group that will be making the final decision and allocating funding for VDOT’s plans for I-66. Construction on the improvements outside of the Beltway began in 2017.[15]

District of Columbia

In Washington, D.C., I-66 follows the West Leg of the Inner Loop freeway. After crossing the Potomac River on the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge concurrent with US 50, the route quickly turns north, separating from US 50. The highway interchanges with the E Street Expressway spur before passing beneath Virginia Avenue in a short tunnel. After an indirect interchange with the Rock Creek Parkway (via 27th Street), the highway terminates at a pair of ramps leading to the Whitehurst Freeway (US 29) and L Street.[16]

This is the only 2 digit Interstate to enter the District of Columbia on land. I-95 crosses DC waters for approximately 100 yards (91 m) along on the Woodrow Wilson Bridge (part of the Capital Beltway).

E Street Expressway

| E Street Expressway | |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Length | 0.30 mi[17] (0.48 km) |

_and_23rd_Street_NW_in_Washington%2C_D.C..jpg)

The E Street Expressway is a spur of I-66 that begins at an interchange with the interstate just north of the Roosevelt Bridge. It proceeds east, has an interchange with Virginia Avenue NW, and terminates at 20th Street NW. From there, traffic continues along E Street NW to 17th Street NW near the White House, the Old Executive Office Building, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Westbound traffic from 17th Street takes a one-block segment of New York Avenue to the expressway entrance at 20th and E Streets NW. The expressway and the connecting portions of E Street and New York Avenue are part of the National Highway System.

- Exit list

The entire route is in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C. All exits are unnumbered.

| mi[17] | km | Destinations | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.00 | Western terminus | |||

| 0.1 | 0.16 | Virginia Avenue / 23rd Street | Eastbound exit only | ||

| 0.1– 0.3 | 0.16– 0.48 | Tunnel underneath Virginia Avenue | |||

| 0.3 | 0.48 | 20th Street / E Street east | Eastern terminus; at-grade intersection | ||

| 1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi | |||||

History

Virginia

I-66 was first proposed in 1956 shortly after Congress established the Highway Trust Fund as a highway to connect Strasburg, Virginia in the Shenandoah Valley with Washington.[18][19]

During the planning stages, the Virginia Highway Department considered four possible locations for the highway inside the Beltway and in 1959 settled on one that followed the Fairfax Drive-Bluemont Drive corridor between the Beltway and Glebe Road (Virginia State Route 120); and then the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) corridor between Glebe Road and Rosslyn in Arlington. The route west of 123 was determined earlier. Two other routes through Arlington neighborhoods and one along Arlington Boulevard were rejected due to cost or opposition.[20] I-66 was originally to connect to the Three Sisters Bridge, but as that bridge was cancelled, it was later designed to connect to the Potomac River Freeway via the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.[21]

On December 16, 1961, the first piece of I-66, an 8.6-mile-long section from US-29 at Gainesville to US-29 at Centreville was opened. A disconnected 3.3-mile-long section near Delaplane in Fauquier County opened next in May 1962.[2]

_from_the_overpass_for_North_Scott_Street_in_Arlington_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

In July 1962, the highway department bought the Rosslyn Spur of the W&OD for $900,000 and began clearing the way, such that by 1965 all that remained was dirt and the shattered foundations of 200 homes cleared for the highway.[22][23][24] In February 1965, the state contracted to buy 30.5 miles of the W&OD from Herndon to Alexandria for $3.5 million and the C&O petitioned the ICC to let them abandon it. The purchase would eliminate the need to build a grade separation for I-66 and would provide 1.5 miles of right-of-way for the highway, saving the state millions.[25] The abandonment proceedings took more than three years, as customers of the railway and transit advocates fought to keep the railroad open, and delayed work on the highway.[26] During that time, on November 10, 1967, WMATA announced that it had come to an agreement with the Highway Department that would give them a 2 year option to buy a five mile stretch of the right of way from Glebe Road to the Beltway, where I-66 was to be built, and run mass transit on the median of it.[27] The W&OD ran its last train during the summer of 1968 thus clearing the way for construction to begin in Arlington.

While the state waited on the W&OD, work continued elsewhere. The Theodore Roosevelt Bridge opened on June 23, 1964 and in November of that year the section from Centerville to the Beltway opened. A 0.2 mile extension from the Roosevelt Bridge to Rosslyn opened in October 1966.[2]

After the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) (then known as the Virginia Department of Highways) took possession of the W&OD right-of-way in 1968, they began to run into opposition as the highway revolts of the late 1960s and early 1970s took hold. In 1970, the Arlington County Board requested new hearings and opponents began to organize marches.[28][29] A significant delay was encountered when the Arlington Coalition on Transportation (ACT) filed a lawsuit in Federal District Court in 1971 opposing the Arlington portion of the project. The group objected to that urban segment due to concerns over air quality, noise, unwanted traffic congestion, wasteful spending, impacts on mass transit and wasted energy by auto travel.[18] In 1972 the U.S. Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of ACT, technically blocking any construction. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the ruling in favor of ACT later that same year.[30]

Again, work continued elsewhere and in October 1971, the 6.6-mile-long section from I-81 to US-340/US-522 north of Front Royal opened.[2]

In July 1974, a final environmental impact statement (EIS) was submitted.[31] The EIS proposed an eight-lane limited access expressway from the Capital Beltway to the area near Spout Run Parkway.[31] Six lanes would branch off at the Parkway and cross the Potomac River via a proposed Three Sisters Bridge.[31] Another six lanes would branch off to the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.[31] In November, a modified design was submitted, reducing the eight lanes to six. However, in 1975, VDOT disapproved the six-lane design.[31]

The parties then agreed on experts to conduct air quality and noise studies for VDOT, selecting the firm of ESL Inc., the expert hired originally by ACT. In 1976, United States Secretary of Transportation William Thaddeus Coleman, Jr. intervened. On January 4, 1977, Coleman approved federal aid for a much narrower, four-lane limited access highway between the Capital Beltway and the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.[31] As part of the deal, Virginia officials agreed to provide more than $100 million in construction work and funds to help build the Metro system, which has tracks down the I-66 median to a station at Vienna in Fairfax County; to build a multi-use trail from Rosslyn to Falls Church; and to limit rush-hour traffic mainly to car pools.[31][32][33] Three more lawsuits would follow, but work began on August 8, 1977 moments after U.S. District Court Judge Owen R. Lewis denied an injunction sought by highway opponents.[34]

In the late 1970s and early 1980s the highway's final miles were built. A 2.9 mile long section from Delaplane to US-17 east of Marshall was completed in 2 sections in 1978 and 1979. The 15.6-mile-long section from US-340 to Delaplane was completed in August 1979. A 12 mile section between US 17 in Marshall and US 15 in Haymarket opened in December 1979, with the gap between Haymarket and Gainesville closed on December 19, 1980.[35] On December 22, 1982, the final section of I-66 opened between the Capital Beltway and U.S. Route 29 (Lee Highway) in Rosslyn, near the Virginia end of the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.[2][31]

The Custis Trail, the trail along I-66 built between Rosslyn and Falls Church as a concession, opened in the summer of 1982, before the highway was complete. The Dulles Connector between I-66 and the airport opened in 1984.[31] The Metrorail in the median of I-66 between Ballston and Vienna, another concession, opened on June 7, 1986.

After opening, the restrictions on use began to loosen. In 1983, Virginia dropped the HOV requirement from 4 to 3,and then from 3 to 2 in 1994. In 1992 motorcycles were allowed.[31]

On October 9, 1999, Public Law 106-69 transferred from the federal government to the Commonwealth of Virginia the authority for the operation, maintenance and construction of I-66 between Rosslyn and the Capital Beltway.[36]

In 2004-05, Virginia studied options for widening the highway inside the Beltway. They later settled on three planned “spot improvements” meant to ease traffic congestion on westbound Interstate 66 inside the Capital Beltway. The first "improvement", a 1.9-mile zone between Fairfax Drive and Sycamore Street, started in 2010 and was finished in 2011.[37] The second one widened 1.675 miles (2.696 km) between the Washington Boulevard on-ramp and the ramp to the Dulles Airport Access Highway. Work on it began in 2013 and finished in 2015.[38] The third project, between Lee Highway/Spout Run and Glebe Road, is scheduled for completion in 2020.[39]

In Gainesville, Virginia, the Gainesville Interchange Project upgraded the interchange between U.S. Route 29 (U.S. 29) and I-66, for those and many other roads due to rapid development and accompanying heavy traffic in the Gainesville and Haymarket area. I-66's overpasses were reconstructed to accommodate nine lanes (six general purpose, two HOV, one collector-distributor eastbound) and lengthened for the expansion of U.S. 29 to six lanes. These alterations were completed in June 2010. In 2014–15, US 29 was largely grade-separated in the area, including an interchange at its current intersection with SR 619 (Linton Hall Road). The project began in 2004 and finished in 2015.[40]

In 2016, VDOT announced that it was planning to add express lanes and multi-modal transportation improvements to I-66 outside the Beltway (the "Transform 66 Outside the Beltway" improvement project). A decision was also made to move forward with widening I-66 eastbound amd make multimodal improvemts from the Dulles Connector Road to Ballston (the "Transform 66 Inside the Beltway" improvement project).[41]

VDOT also announced during 2016 that it would initiate on I-66 a dynamic tolling system in the peak travel directions during rush hours. On December 4, 2017, VDOT converted 10 miles (16.1 km) of I-66 between Route 29 in Rosslyn and the Capital Beltway to a High Occupancy Vehicle variable congestion pricing tolling system. The system permits solo drivers to use I-66 during peak travel hours in the appropriate direction if they pay a toll.[42]

VDOT designed the price of toll to keep traffic moving at a minimum of 45 mph (72 km/h) and to increase the capacity of the road. Carpools and vanpools (with two or more people, until a regional change to HOV-3+ goes into effect in 2022), transit, on-duty law enforcement and first responders will not pay a toll.[43] Prices ranged up to $47 USD for solo drivers, but the average speed during the morning rush hour was 57 mph (92 km/h), vs 37 miles per hour (60 km/h) a year before.[44]

In 2017, construction began on the "Transform 66 Outside the Beltway" improvement project. The project will add 22.5 miles (36.2 km) of new dynamically-tolled Express Lanes alongside I-66 from I-495 to University Boulevard in Gainesville. It will also build new park and ride facilities, interchange improvements and 11 miles (17.7 km) of expanded multi-use trail. VDOT expects the project to be completed in December 2022.[45]

_at_the_eastern_end_of_Interstate_66_(Potomac_River_Freeway)_in_Washington%2C_D.C..jpg)

Construction on widening eastbound I-66 as part of the "Transform 66 Inside the Beltway" improvement project began in June 2018 and is expected to be completed in 2020. The project will add a travel lane on eastbound I-66 between the Dulles Access Road (Virginia State Route 267) and Fairfax Drive (Exit 71) in Ballston, will provide a new ramp-to-ramp direct access connection from eastbound I-66 to the West Falls Church Metro station at the Leesburg Pike (Virginia State Route 7) interchange and will provide a new bridge for the W&OD Trail over Lee Highway (Virginia State Route 29).[43]

VDOT completed in August 2018 a diverging diamond interchange in Haymarket at the interchange of I-66 with U.S. Route 15.[46]

District of Columbia

_from_the_overpass_for_Triangle_Park-Virginia_Avenue-New_Hampshire_Avenue-25th_Street_in_Washington%2C_D.C..jpg)

In Washington D.C., I-66 was planned to extend east of its current terminus along the North Leg of the Inner Loop freeway. I-66 would have also met the eastern terminus of a planned Interstate 266 at US 29, and the western terminus of the South Leg Freeway (I-695) at US 50; I-266 would have been a parallel route to I-66, providing more direct access to the North Leg from points west, while I-695 would have been an inner-city connector between I-66 and I-95.

The final plans for the North Leg Freeway, as published in 1971, outlined a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) six-lane tunnel beneath K Street, between I-266/US 29 and New York Avenue, where the North Leg would emerge from the tunnel and join with the Center Leg Freeway (formerly I-95, now I-395); the two routes would run concurrently for three-fourths of a mile before reaching the Union Station interchange, where I-66 was planned to terminate. Despite the plan to route the North Leg in a tunnel beneath K Street, the intense opposition to previous, scrapped alignments for the D.C. freeway network, which included previous alignments for the North Leg Freeway, led to the mass cancellation of all unbuilt D.C. freeways in 1977, resulting in the truncation of I-66 at US 29.

Exit list

All exits in the District of Columbia are unnumbered.

| State/district | County | Location | mi[47] | km | Old exit | New exit | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia | Frederick | | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | Signed as exits 1A (south) and 1B (north); exit 300 on I-81; tri-stack interchange | ||

| Warren | Front Royal | 6.4 | 10.3 | 2 | 6 | |||

| | 12.9 | 20.8 | 3 | 13 | ||||

| Fauquier | Markham | 18.5 | 29.8 | 4 | 18 | |||

| Delaplane | 23.3 | 37.5 | 5 | 23 | Western terminus of US 17 / SR 55 concurrency | |||

| | 27.0 | 43.5 | 6 | 27 | Eastern terminus of SR 55 concurrency; former SR 242 south | |||

| | 28.3 | 45.5 | 7 | 28 | Eastern terminus of US 17 concurrency | |||

| | 31.3 | 50.4 | 8 | 31 | ||||

| Prince William | Haymarket | 40.5 | 65.2 | 9 | 40 | Diverging diamond interchange | ||

| Gainesville | 43.1 | 69.4 | 10 | 43 | Signed as exits 43A (south) and 43B (north) | |||

| | 44.5 | 71.6 | 11 | 44 | Western terminus of SR 234 concurrency | |||

| | 47.3 | 76.1 | 12 | 47 | Eastern terminus of SR 234 concurrency; signed as exits 47A (south) and 47B (north) westbound | |||

| | 48.8 | 78.5 | Rest area | |||||

| Fairfax | Centreville | 52.1 | 83.8 | 13 | 52 | |||

| Centreville–Chantilly line | 53.2 | 85.6 | 14 | 53B | Signed as exit 53 eastbound; no westbound entrance | |||

| 53A | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||||||

| Fair Lakes | 54.9 | 88.4 | — | Stringfellow Road (SR 645) | Westbound exit or eastbound entrance via reversible HOV ramp[48] | |||

| 55.9 | 90.0 | 15 | 55 | Signed as exits 55A (south) and 55B (north) | ||||

| Fair Oaks | 57.1 | 91.9 | — | Monument Drive (SR 6751) | HOV westbound exit and eastbound entrance[48] | |||

| 58.1 | 93.5 | 16 | 57 | Signed as exits 57A (east) and 57B (west) | ||||

| Oakton | 60.1 | 96.7 | 17 | 60 | ||||

| 61.6 | 99.1 | 17A | 62 | Accessible via C/D lanes | ||||

| Oakton–Merrifield line | 62.5 | 100.6 | ||||||

| Dunn Loring–Merrifield– Idylwood tripoint | 65.1 | 104.8 | 18 | 64A | Signed as exit 64 westbound; exit 49 on I-495 | |||

| 64B | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance; exit 49 on I-495 | |||||||

| — | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||||||

| Idylwood | Toll gantry (non-HOV2+ vehicles, peak-direction only)[9] | |||||||

| Pimmit Hills–Idylwood line | 66.0 | 106.2 | 19 | 66 | Signed as exits 66A (east) and 66B (west) westbound; serves West Falls Church station | |||

| 66.6 | 107.2 | 20 | 67 | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; eastern terminus of SR 267 | ||||

| Westhampton | Toll gantry (non-HOV2+ vehicles, peak-direction only)[9] | |||||||

| Arlington | East Falls Church | 67.8 | 109.1 | 21 | 68 | Westmoreland Street | Eastbound exit only | |

| 68.4 | 110.1 | 22 | 69 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||||

| 23 | 69 | Sycamore Street – Falls Church | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance; serves East Falls Church station | |||||

| Bluemont | Toll gantry (non-HOV2+ vehicles, peak-direction only)[9] | |||||||

| Ballston | 70.5 | 113.5 | 24 | 71 | Serves Ballston–MU station | |||

| Cherrydale | Toll gantry (non-HOV2+ vehicles, peak-direction only)[9] | |||||||

| Maywood | 72.1 | 116.0 | 25 | 72 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||

| Rosslyn | 73.1 | 117.6 | 26 | 73 | ||||

| 74.2 | 119.4 | 27 | 75 | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||||

| Virginia–D.C. line | Arlington–Washington line | 74.8 0.0 | 120.4 0.0 | Theodore Roosevelt Bridge over the Potomac River | ||||

| 0.1 | 0.16 | — | Western terminus of US 50 concurrency; westbound exit and eastbound entrance | |||||

| District of Columbia | Washington | 0.5 | 0.80 | — | Independence Avenue | Eastbound exit only | ||

| — | Eastern terminus of US 50 concurrency; eastbound exit and westbound entrance | |||||||

| 0.7 | 1.1 | — | E Street Expressway east | Western terminus of the E Street Expressway | ||||

| 0.8 | 1.3 | — | Kennedy Center | Westbound entrance only | ||||

| 0.9 | 1.4 | — | Independence Avenue / Maine Avenue | Westbound exit and eastbound entrance | ||||

| 1.2 | 1.9 | — | Rock Creek Parkway | Eastbound exit and westbound entrance | ||||

| 1.4 | 2.3 | — | Pennsylvania Avenue | Eastbound exit only | ||||

| 1.6 | 2.6 | — | Whitehurst Freeway (US 29 south) to Canal Road | Eastern terminus | ||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||||

Auxiliary routes

| |

|---|---|

| Location | Arlington, Virginia–Washington, D.C. |

| Length | 1.79 mi (2.88 km) |

| Existed | 1960s–1972 |

Interstate 266 (I-266) was a proposed loop route of I-66 between Washington, D.C., and Arlington County, Virginia. District of Columbia officials proposed designating the route Interstate 66N, a move opposed by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. In Virginia, Interstate 266 would have split off from Interstate 66 just east of the present Spout Run Parkway exit. From there, it would have followed an expanded Spout Run Parkway, crossed the George Washington Memorial Parkway, and crossed the Potomac River across a new bridge that would have been called the Three Sisters Bridge. Upon entering the District of Columbia, it would have followed Canal Road and an expanded Whitehurst Freeway to rejoin Interstate 66 at K Street. Interstate 266 was canceled in 1972 in the face of community opposition during Washington's "freeway revolts".[49][50]

References

- "Table 1: Main Routes of the Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways as of October 31, 2002". Route Log and Finder List. Federal Highway Administration. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012.

- Kozel, Scott. "Interstate 66 in Virginia". Roads to the Future. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Google (June 8, 2009). "Interstate 66" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- Google (June 8, 2009). "Interstate 66" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

- "Department of Planning & Zoning – Planning Zoning" (PDF). www.fairfaxcounty.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2018.

- Shaffer, Ron (October 21, 2005). "Dr. Gridlock". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- "I-66 Spot Improvements-Spot 1". Virginia Department of Transportation. August 25, 2011. Archived from the original on August 8, 2011.

- "Arlington Virginia List of State Roads". Environmental Services. Government of Arlington County, Virginia. Archived from the original on March 4, 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- "66 Express Lanes - Inside the Beltway :: Using the Lanes". 66expresslanes.org. Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- Thomson, Robert (February 18, 2015). "I-66 HOT lanes plan reviewed by regional panel". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 8, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- "Commentary: Business groups urge action on I-66 outside the Beltway". INSIDENOVA.COM.

- "Officials to consider road widening, HOT lanes through Arlington portion of I-66". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

- "Deal close to save homes from I-66 widening". WTOP. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015.

- "CTB Member Roll" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 18, 2015.

- "Transform 66 in Northern Virginia – Outside the Beltway". outside.transform66.org. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- The 2014 Road Atlas (Map). Rand McNally. 2014. p. 111.

- Google (January 31, 2020). "E Street Expressway" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Lynton, Stephen (December 22, 1982). "A Long Road Bitter Fight Against I-66 Now History". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Guinn, Muriel (June 18, 1958). "Approach to Airport Urged for Highway 66". The Washington Post.

- Lawson, Jack (February 20, 1959). "Arlington Corridor Chosen For Interstate Highway 66". The Washington Post.

- Ladner, George (September 19, 1964). "Committee Will Await Public Reaction Before Deciding on Site for Bridge". The Washington Post.

- "Rail Spur Quiet for While: But the Old W&OD Route Soon Will Hum With Autos". The Washington Post. November 16, 1964.

- "W&OD Rail Spur Bought by State". The Washington Post. July 10, 1962.

- Cheek, Leslie (October 15, 1965). "I-66 in Arlington Planned As Model of Road Beauty". The Washington Post.

- "ICC Examiner Favors Death of W&OD Line". The Washington Post. March 8, 1966.

- "Ailing Va. Railroad Allowed to Quit in '68". The Washington Post. January 25, 1968.

- Corrigen, Richard (November 2, 1967). "WMATA Agrees On Rail Bed Route". The Washington Post.

- "1-66 Opponents Schedule Walk". The Washington Post. October 25, 1970.

- "ew Hearing Requested On Va. Designs for I-66". The Washington Post. October 5, 1970.

- Mathews, Jay (November 7, 1972). "High Court Backs Delay of Rte. 66". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- "Background: I-66 History". Idea-66. Virginia Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- "An Abridged I-66 Chronology". The Arlington Coalition for Sensible Transportation. Archived from the original on August 9, 2006. Retrieved February 5, 2006.

- Hogan, C. M. & Seidman, Harry (1971). Air Quality and Acoustics Analysis of Proposed I-66 through Arlington, Virginia. Sunnyvale, CA: ESL Inc. Technical Document T1026.

- Boodman, Sandra; McCallister, Bill (August 9, 1977). "Virginia Crew Starts Clearing Path for I-66". The Washington Post.

- "12 More Miles of I-66". The Washington Post. December 27, 1979.

- "Department of Transportation and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2000: Public Law 106-69: 106th Congress" (pdf). Sec. 357. United States Government Printing Office. October 9, 1999. p. 113 Stat. 1027. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

Sec. 357. (a) Notwithstanding the January 4, 1977, decision of the Secretary of Transportation that approved construction of Interstate Highway 66 between the Capital Beltway and Rosslyn, Virginia, the Commonwealth of Virginia, in accordance with existing Federal and State law, shall hereafter have authority for operation, maintenance, and construction of Interstate Route 66 between Rosslyn and the Capital Beltway, except as noted in paragraph (b).

(b) The conditions in the Secretary's January 4, 1997 decision, that exclude heavy duty trucks and permit use by vehicles bound to or from Washington Dulles International Airport in the peak direction during peak hours, shall remain in effect. - Thompson, Robert (October 18, 2013). "Work to begin on second 'spot improvement' for I-66". Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "I-66 Spot 2 Improvements Project". Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "I-66 Multimodal Improvement Project inside the Capital Beltway". Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Gainesville Interchange Project". 2011. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- "PLANS TO EXTEND I-395 EXPRESS LANES LAUNCHED" (PDF). Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- Lazo, Luz (December 2, 2017). "Interstate 66 tolling starts Monday. Here's what you need to know". Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Transform 66 in Northern Virginia". Inside the Beltway. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- (1) "Are $40 Toll Roads The Future?". NPR. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

(2) "Tolls stabilize during first afternoon rush hour on I-66 inside Beltway". Washington, DC: WTOP. December 4, 2017. Archived from the original on December 13, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2017. - "About the Project". Retrieved October 12, 2018.

- "Diverging-diamond completion to be celebrated in Haymarket". InsideNova. August 9, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

- Google (January 31, 2020). "Interstate 66" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- "I-66 West HOV Ramps Now Open Off-Peak and Weekends" (Press release). February 28, 2011. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- Archived August 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "3-digit Interstates from I-66". Kurumi.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Interstate 66. |

- Transform 66 Outside the Beltway Project

- HOV schedule in Northern Virginia, from Virginia Dept. of Transportation

- Roads to the Future: Washington D.C. Interstates and Freeways

- Steve Anderson's DCRoads.net: Interstate 66 (Virginia)

| Browse numbered routes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ← | VA | SR 67 | ||

| ← | DC | I-95 | ||