Gilgit Agency

The Gilgit Agency (Urdu: گلگت ایجنسی) was a system of administration established by the British Indian Empire over the subsidiary states of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir at its northern periphery, mainly with the objective of strengthening these territories against Russian encroachment.

| Gilgit Agency | |

|---|---|

| Agency | |

| 1889–1974 | |

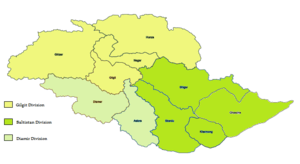

Gilgit Agency in the Kashmir region, c. 1970 | |

| History | |

• British Political agent | 1889 |

• Gilgit Wazarat leased | 26 March 1935 |

• Lease terminated | 30 July 1947 |

• Gilgit rebellion | 1 November 1947 |

• Pakistani Political agent | 19 November 1947 |

• Merged into Northern Areas | 1974 |

| "A collection of treaties, engagements, and sunnuds relating to India and neighbouring countries" | |

An Officer on Special Duty was established in 1877 in the town of Gilgit, upgraded to a permanent Political Agent in 1889. In 1935, the Gilgit district (wazarat) of the princely state was leased from the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir, which also came under the administration of the Political Agent. In July 1947, shortly before the independence of India and Pakistan, these areas were returned to the Maharaja. However, the Gilgit Scouts rebelled on 1 November 1947 after the accession of Jammu and Kashmir to India, and Pakistan took over the administration of the areas soon thereafter.[1][2]

Under Pakistani administration, the Gilgit district as well as the subsidiary states were clubbed together under the name the "Gilgit Agency". It remained in existence till about 1974, when the unit was abolished by the Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and made part of Federally Administered Northern Areas (later renamed to "Gilgit-Baltistan").[3]

India continues to claim the entire region as part of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.[4][5][6]

Area and borders

The areas under the Gilgit Agency consisted of

- the state of Chilas and the territories of Darel & Tangir (present day Diamer District)

- Punial, Yasin, Kuh-Ghizar, and Ishkoman regions (present day Ghizer District)

- the states of Hunza and Nagar (present day Hunza and Nagar districts).

All these states had their own rulers or systems of administration; the Agency provided supervision.[7][8]

Until 1935, the present day Gilgit and Astore districts comprised the Gilgit wazarat of Jammu and Kashmir with its own governor (wazir-e-wazarat). However, the Political Agent did exercise some control over its affairs, leading to a system of 'dyarchy'.[7][8]

In 1935, the British leased the Gilgit tehsil as the "Gilgit (Leased Area)". It was administered directly by the Political Agent. The Astore tehsil became its own wazarat, which was administered as part of the Kashmir province of Jammu and Kashmir.[9]

In 1941, the Gilgit Agency had a population of 77,000 and the Gilgit leased area had 23,000. Both the areas together came to be loosely referred to as the 'Gilgit Agency'. The administration of the Agency was carried out "on behalf of His Highness’ Government". The Political Agent communicated with the central government in New Delhi via Peshawar (the capital of the North-West Frontier Province) for reasons of security.[10]

The administered area was bounded in the west by the Chitral State, in the northwest by Afghanistan's Wakhan corridor, in the east by Chinese Turkestan, in the south by the Kashmir province, and in the southeast by the Ladakh–Baltistan wazarat of Jammu and Kashmir.

Background

| Princely state |

|---|

| Individual residencies |

|

| Agencies |

|

| Lists |

The Treaty of Amritsar (1846) granted to Raja Gulab Singh the entirety of the Sikh Empire.

During the First Anglo-Sikh War, Maharaja Gulab Singh Jamwal (Dogra) helped the British Empire against the Sikhs.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] After the defeat of the Sikh Empire, The Treaty of Lahore (9 March 1846) and the Treaty of Amritsar (1846) (16 March 1846) were signed. Under Article IV of The Treaty of Lahore, signed between the Maharaja Duleep Singh (Sikh) (4 September 1838 – 22 October 1893) and the British Empire taxes could be collected in the territories between the Ravi and the Indus for the indemnification for the expenses of the war.

IV. The British Government having demanded from the Lahore State, as indemnification for the expenses of the war, in addition to the cession of territory described in Article 3, payment of one and half crore of Rupees, and the Lahore Government being unable to pay the whole of this sum at this time, or to give security satisfactory to the British Government for its eventual payment, the Maharajah cedes to the Honourable Company, in perpetual sovereignty, as equivalent for one crore of Rupees, all his forts, territories, rights and interests in the hill countries, which are situated between the Rivers Beas and Indus, including the Provinces of Cashmere and Hazarah.

In the north, these territories included Gilgit (the present Gilgit District), Astore (the present Astore District) and Chilas (presently a tehsil of the Diamir District).[24] By 1860, the three areas were constituted as a Gilgit wazarat (district), and the princely states of Hunza and Nagar to the northeast accepted the suzerainty of the Maharaja Ranbir Singh.[25]

The Treaty of Amritsar did not constrain the Maharaja from establishing relationships with external powers, and he is said to have had dealings with Russia, Afghanistan and Chinese Turkestan. The British watched these developments with concern, especially in the light of Russian expansion in the north.[26]

Establishment of the Agency

Ranbir Singh's successor Pratap Singh was a weak ruler. The British used the opportunity to establish an Agency in Gilgit in 1889, stationing a Political Agent who reported to the British Resident in Srinagar. The initial purpose of the Agency was to keep watch on the frontier and to restrain Hunza and Nagar from dealing with the Russians. Soon afterwards, the states of Hunza and Nagar were brought under the direct purview of the Gilgit Agency. The Jammu and Kashmir State Forces were stationed in a garrison at Gilgit, which were used by the Agency to keep order. They were replaced by a British-officered Gilgit Scouts in 1913.[27]

Gradually, the princely states to the west of Gilgit (Punial, Yasin, Kuh-Ghizar, Ishkoman and Chitral) were also brought under the purview of the Gilgit Agency. These areas were nominally under the suzerainty of Kashmir but were directly administered by the Agency.[28] Following a rebellion 1892, Chitral was transferred to the Malakand Agency in the Frontier Areas.[29] The remaining areas remained under the control of the Gilgit Agency, which administered them through governors.[28]

Inside Pakistan

The local rulers of these territories continued to appear at the Jammu and Kashmir Durbars until 1947. Following the Partition of India, on 31 October 1947 the British officer William Brown led the Gilgit Scouts in a coup against the Dogra governor of Gilgit which resulted in the region becoming part of Pakistan administered Kashmir. Most of the Ladakh Wazarat, including the Kargil area, became part of Indian-administered Kashmir. The Line of Control established at the end of the war is the current de facto border of India and Pakistan.

Initially, the Gilgit Agency was not absorbed into any of the provinces of West Pakistan, but was ruled directly by political agents of the federal government of Pakistan. In 1963, Pakistan entered into a treaty with China to transfer part of the Gilgit Agency to China, (the Trans-Karakoram Tract), with the proviso that the settlement was subject to the final solution of the Kashmir dispute.

The dissolution of the province of West Pakistan in 1970 was accompanied by change of the name of the Gilgit Agency to the Northern Areas. In 1974, the states of Hunza and Nagar and the independent valleys of Darel-Tangir, which had been de facto dependencies of Pakistan, were also incorporated into the Northern Areas.

Pakistan and India continue to dispute the sovereignty of the territories that had comprised the Gilgit Agency.

See also

- Baltistan

- Gilgit

- Northern Areas

- Kashmir

- Kashmir Conflict

- Trans-Karakoram Tract

References

- Snedden, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris (2015).

- Bangash, Three Forgotten Accesions (2010).

- Ali, Nosheen (2019), Delusional States, Cambridge University Press, pp. 33–34, ISBN 978-1-108-49744-2

- "Political Map of India".

- "Govt releases new political map of India showing UTs of J&K, Ladakh | India News - Times of India". The Times of India.

- "J&K Reorganisation (Removal of Difficulties) Second Order, 2019 -- [Territory of Leh district shall constitute, Gilgit, Gilgit Wazarat, Chilas, Tribal territory & 'Leh & Ladakh' except present territory of Kargil]". 2 November 2019.

- Snedden, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris (2015), Appendix V.

- Bangash, Three Forgotten Accesions (2010), p. 122.

- Census of India, 1941, Volume XXII (1943), p. 3.

- Snedden, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris (2015), p. 118.

- Fenech, E. Louis; Mcleod, H. W. (11 June 2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- G. S. Chhabra. Advance Study in the History of Modern India (Volume-2: 1803-1920). p. 188.

- William Brown. Gilgit Rebelion: The Major Who Mutinied Over Partition of India Kindle Edition.

- William A. Brown. THE GILGIT REBELLION 1947.

- Pranay Gupte. Mother India: A Political Biography of Indira Gandhi. p. 266.

- Stanley Wolpert. India and Pakistan: Continued Conflict Or Cooperation?. p. 21.

- Christopher Snedden. Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris. p. 67.

- Bawa, Satinder Singh. The Jammu Fox: A Biography of Maharaja Gulab Singh of Kashmir, 1792-1857. p. 263.

- Mridu Rai. Hindu Rulers, Muslim Subjects: Islam, Rights, and the History of Kashmir. p. 20.

- Raja Afsar Khan, 2006 - Islam. The Concept, Volume 26, Issues 1-6. p. 42.

- Vijay Kumar. Anglo-American Plot Against Kashmir. People's Publishing House, 1954 - Jammu and Kashmir. p. 10.

- G. M. D. Sufi. Kashir, Being a History of Kashmir from the Earliest Times to Our Own, Volume 2. Light & Life Publishers, 1974 - Jammu and Kashmir.

- Satinder Singh Bawa. Gulab Singh of Jammu, Ladakh, and Kashmir, 1792-1846 University of Wisconsin--Madison, 1966. p. 218.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict (2003), p. 20.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict (2003), p. 11.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict (2003), p. 12.

- Schofield, Kashmir in Conflict (2003), pp. 12–13.

- Chohan, Gilgit Agency (1997), p. 203.

- Snedden, Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris (2015), p. 110.

Bibliography

- Census of India, 1941, Volume XXII – Jammu and Kashmir, Parts I & II, The Ranbir Government Press, 1943

- Bangash, Yaqoob Khan (2010), "Three Forgotten Accessions: Gilgit, Hunza and Nagar", The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38 (1): 117–143, doi:10.1080/03086530903538269

- Chohan, Amar Singh (1997), Gilgit Agency 1877–1935, Second Reprint, Atlantic Publishers & Dist, ISBN 978-81-7156-146-9

- Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, ISBN 1-86064-898-3

- Snedden, Christopher (2015), Understanding Kashmir and Kashmiris, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-1-84904-342-7

External links

- Jammu and Kashmir Official Website

- Northern Areas Official Website

- Northern Areas Census (1998)

- Northern Areas Administration

- Northern Areas Map