Education in Pakistan

Education in Pakistan is overseen by the Federal Ministry of Education and the provincial governments, whereas the federal government mostly assists in curriculum development, accreditation and in the financing of research and development. Article 25-A of Constitution of Pakistan obligates the state to provide free and compulsory quality education to children of the age group 5 to 16 years. "The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to sixteen years in such a manner as may be determined by law".[3]

| |

| Federal Ministry of Education | |

|---|---|

| Literacy (2020[1]) | |

| Total | 73.3% |

| Male | 82.5% |

| Female | 59.8% |

| Enrollment | |

| Total | 50,616,000[2] |

| Primary | 22,650,010[2] |

| Secondary | 2,884,400[2] |

| Post secondary | 1,949,000[2] |

The education system in Pakistan[4] is generally divided into six levels: preschool (for the age from 3 to 5 years), primary (grades one through five), middle (grades six through eight), high (grades nine and ten, leading to the Secondary School Certificate or SSC), intermediate (grades eleven and twelve, leading to a Higher Secondary School Certificate or HSSC), and university programs leading to undergraduate and graduate degrees.[5]

The literacy rate ranges from 85% in Islamabad to 23% in the Torghar District.[6] Literacy rates vary regionally, particularly by sex. In tribal areas female literacy is 9.5%.,[7] while Azad Jammu & Kashmir has a literacy rate of 74%.[8] Moreover, English is fast spreading in Pakistan, with more than 92 million Pakistanis (49% of the population) having a command over the English language. On top of that, Pakistan produces about 445,000 university graduates and 80,000 computer science graduates per year.[9] Despite these statistics, Pakistan still has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world[10] and the second largest out of school population (22.8 million children)[11] after Nigeria.

Stages of formal education

Primary education

Only 68% of Pakistani children finish primary school education.[12] The standard national system of education is mainly inspired from the English educational system. Pre-school education is designed for 3–5 years old and usually consists of three stages: Play Group, Nursery and Kindergarten (also called 'KG' or 'Prep'). After pre-school education, students go through junior school from grades 1 to 5. This is followed by middle school from grades 6 to 8. At middle school, single-sex education is usually preferred by the community, but co-education is also common in urban cities. The curriculum is usually subject to the institution. The eight commonly examined disciplines are:

- Arts

- Computer Studies and ICT

- General Science (including Physics, Chemistry and Biology)

- Modern languages with literature i.e. Urdu and English

- Mathematics

- Religious Education i.e. Islamic Studies

- Social Studies (including Civics, Geography, History, Economics, Sociology and sometimes elements of law, politics and PHSE)

Most schools also offer drama studies, music and physical education but these are usually not examined or marked. Home economics is sometimes taught to female students, whereas topics related to astronomy, environmental management and psychology are frequently included in textbooks of general science. Sometimes archaeology and anthropology are extensively taught in textbooks of social studies. SRE is not taught at most schools in Pakistan although this trend is being rebuked by some urban schools. Provincial and regional languages such as Punjabi, Sindhi, Pashto and others may be taught in their respective provinces, particularly in language-medium schools. Some institutes give instruction in foreign languages such as German, Turkish, Arabic, Persian, French and Chinese. The language of instruction depends on the nature of the institution itself, whether it is an English-medium school or an Urdu-medium school.

As of 2009, Pakistan faces a net primary school attendance rate for both sexes of 66 percent: a figure below estimated world average of 90 percent.[13]

Pakistan's poor performance in the education sector is mainly caused by the low level of public investment. As of 2007, public expenditure on education was 2.2 percent of GNPs, a marginal increase from 2 percent before 1984-85. In addition, the allocation of government funds is skewed towards higher education, allowing the upper income class to reap the majority of the benefits of public subsidy on education. Lower education institutions such as primary schools suffer under such conditions as the lower income classes are unable to enjoy subsidies and quality education. As a result, Pakistan has one of the lowest rates of literacy in the world and the lowest among countries of comparative resources and socio-economic situations.[14]

Secondary education

Secondary education in Pakistan begins from grade 9 and lasts for four years. After end of each of the school years, students are required to pass a national examination administered by a regional Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education (or BISE).

Upon completion of grade 9, students are expected to take a standardised test in each of the first parts of their academic subjects. They again give these tests of the second parts of the same courses at the end of grade 10. Upon successful completion of these examinations, they are awarded a Secondary School Certificate (or SSC). This is locally termed a 'matriculation certificate' or 'matric' for short. The curriculum usually includes a combination of eight courses including electives (such as Biology, Chemistry, Computer and Physics) as well as compulsory subjects (such as Mathematics, English, Urdu, Islamic studies and Pakistan Studies).

Students then enter an intermediate college and complete grades 11 and 12. Upon completion of each of the two grades, they again take standardised tests in their academic subjects. Upon successful completion of these examinations, students are awarded the Higher Secondary School Certificate (or HSSC). This level of education is also called the FSc/FA/ICS or 'intermediate'. There are many streams students can choose for their 11 and 12 grades, such as pre-medical, pre-engineering, humanities (or social sciences), computer science and commerce. Each stream consists of three electives and as well as three compulsory subjects of English, Urdu, Islamiat (grade 11 only) and Pakistan Studies (grade 12 only).

Alternative qualifications in Pakistan are available but are maintained by other examination boards instead of BISE. Most common alternative is the General Certificate of Education (or GCE), where SSC and HSSC are replaced by Ordinary Level (or O Level) and Advanced Level (or A Level) respectively. Other qualifications include IGCSE which replaces SSC. GCE and GCSE O Level, IGCSE and GCE AS/A Level are managed by British examination boards of CIE of the Cambridge Assessment and/or Edexcel International of the Pearson PLC. Generally, 8-10 courses are selected by students at GCE O Levels and 3-5 at GCE A Levels.

Advanced Placement (or AP) is an alternative option but much less common than GCE or IGCSE. This replaces the secondary school education as 'High School Education' instead. AP exams are monitored by a North American examination board, College Board, and can only be given under supervision of centers which are registered with the College Board, unlike GCE O/AS/A Level and IGCSE which can be given privately.

Another type of education in Pakistan is called "Technical Education" and combines technical and vocational education. The vocational curriculum starts at grade 5 and ends with grade 10.[15] Three boards, the Punjab Board of Technical Education (PBTE), KPK Board of Technical Education (KPKBTE) and Sindh Board of Technical Education (SBTE) offering Matric Tech. course called Technical School Certificate (TSC) (equivalent to 10th grade) and Diploma of Associate Engineering (DAE) in engineering disciplines like Civil, Chemical, Architecture, Mechanical, Electrical, Electronics, Computer etc. DAE is a three years program of instructions which is equivalent to 12th grade. Diploma holders are called associate engineers. They can either join their respective field or take admission in B.Tech. and BE in their related discipline after DAE.

Furthermore, the A level qualification, inherited by the British education system is widely gained in the private schools of Pakistan. Three to four subjects are selected, based on the interest of the student. It is usually divided into a combination of similar subjects within the same category, like Business, Arts and Sciences. This is a two-year program. A level institutions are different from high school. You must secure admission in such an institution, upon the completion of high school, i.e. the British system equivalent being O levels. O levels and A levels are usually not taught within the same school.

Tertiary education

According to UNESCO's 2009 Global Education Digest, 6% of Pakistanis (9% of men and 3.5% of women) were university graduates as of 2007.[16] Pakistan plans to increase this figure to 10% by 2015 and subsequently to 15% by 2020.[17] There is also a great deal of variety between age cohorts. Less than 6% of those in the age cohort 55-64 have a degree, compared to 8% in the 45-54 age cohort, 11% in the 35-44 age cohort and 16% in the age cohort 25-34.[16]

.jpg)

After earning their HSSC, students may study in a professional institute for Bachelor's degree courses such as engineering (BE/BS/BSc Engineering), medicine (MBBS), dentistry (BDS), veterinary medicine (DVM), law (LLB), architecture (BArch), pharmacy (Pharm.D) and nursing (BSc Nursing). These courses require four or five years of study. The accreditation councils which accredit the above professional degrees and register these professionals are: Pakistan Engineering Council (PEC), Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC), Pakistan Veterinary Medical Council (PVMC), Pakistan Bar Council (PBC), Pakistan Council for Architects and Town Planners (PCATP), Pharmacy Council of Pakistan (PCP) and Pakistan Nursing Council (PNC). Students can also attend a university for Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BSc), Bachelor of Commerce (BCom) or Bachelor of Business Administration (BBA) degree courses.

There are two types of Bachelor courses in Pakistan: Pass or Honors. Pass degree requires two years of study and students normally read three optional subjects (such as Chemistry or Economics) in addition to almost equal number of compulsory subjects (such as English, islamiyat and Pakistan Studies). Honours degree requires four years of study, and students normally specialize in a chosen field of study, such as Biochemistry (BSc Hons. Biochemistry).

Pass Bachelors is now slowly being phased out for Honours throughout the country.

Quaternary education

Most of Master's degree programs require two years education. Master of Philosophy (MPhil) is available in most of the subjects and can be undertaken after doing Masters. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) education is available in selected areas and is usually pursued after earning a MPhil degree. Students pursuing MPhil or PhD degrees must choose a specific field and a university that is doing research work in that field. MPhil and PhD education in Pakistan requires a minimum of two years of study.

Nonformal and informal education

Out of the formal system, the public sectors runs numerous schools and training centres, most being vocational-oriented. Among those institutions can be found vocational schools, technical training centres and agriculture and vocational training centres. An apprenticeship system is also framed by the state of Pakistan.[15] Informal education is also important in Pakistan and regroups mostly school-leavers and low-skilled individuals, who are trained under the supervision of a senior craftsman.[15] Few institutes are run by corporates to train university students eligible for jobs and provide experience during education fulfilling a gap between university and industry for example: Appxone Private Limited is training Engineers with professional development on major subjects of Electronics and Computer science and other fields.

Madrassas

Madrassas are Islamic seminaries. Most Madrasas teach mostly Islamic subjects such as Tafseer (Interpretation of the Quran), Hadith (sayings of Muhammad), Fiqh (Islamic Law), Arabic language and include some non-Islamic subjects, such as logic, philosophy, mathematics, to enable students to understand the religious ones. The number of madrassas are popular among Pakistan's poorest families in part because they feed and house their students. Estimates of the number of madrasas vary between 12,000 and 40,000. In some areas of Pakistan they outnumber the public schools.[18]

Gender disparity

In Pakistan, gender discrimination in education occurs among the poorest households but is non-existent among rich households.[19] Only 18% of Pakistani women have received 10 years or more of schooling.[19] Among other criticisms the Pakistani education system faces is the gender disparity in enrollment levels. However, in recent years some progress has been made in trying to fix this problem. In 1990-91, the female to male ratio (F/M ratio) of enrollment was 0.47 for primary level of education. It reached to 0.74 in 1999-2000, showing the F/M ratio has improved by 57.44% within the decade. For the middle level of education it was 0.42 in the start of decade and increased to 0.68 by the end of decade, so it has improved almost 62%. In both cases the gender disparity is decreased but relatively more rapidly at middle level.[20]

The gender disparity in enrollment at secondary level of education was 0.4 in 1990-91 and 0.67 in 1999-2000, showing that the disparity decreased by 67.5% in the decade. At the college level, it was 0.50 in 1990-91 and reached 0.81 in 1999-2000, showing that the disparity decreased by 64%. The gender disparity has decreased comparatively rapidly at secondary school.[20]

There is great difference in the rates of enrollment of boys, as compared to girls in Pakistan. According to UNESCO figures, primary school enrollment for girls stand at 60 per cent as compared to 84 percent for boys. The secondary school enrollment rate stands at a lower rate of 32 percent for females and 46 per cent males. Regular school attendance for female students is estimated at 41 per cent while that for male students is 50 per cent.[13]

A particularly interesting aspect of this gender disparity is representation of Pakistani women in STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine). In 2013, the issue of women doctors in Pakistan was highlighted in local and international media.[21][22][23][24] According to Pakistan Medical and Dental Council, in many medical colleges in Pakistan, as many as 80% of students are women, but majority of these women do not go on to actually practice medicine, creating a shortage of doctors in rural areas and several specialties (especially surgical fields).[22][24] In 2014, Pakistan Medical and Dental Council introduced a gender-based admission policy, restricting women to 50% of available seats (based on the gender ratios in general population).[25][26] This quota was challenged and subsequently deemed unconstitutional (and discriminatory) by Lahore High Court.[27][28] Research indicates several problems faced by women doctors in Pakistan in their career and education, including lack of implementation of women-friendly policies (like maternity leave, breast-feeding provisions and child-care facilities), and systemic sexism prevalent in medical education and training.[29] Pakistan's patriarchal culture, where women's work outside the home is generally considered less important than her family and household obligations, also make it difficult for women to balance a demanding career.[29] Despite the importance of the issue, no new policies (except now-defunct-quota) have been proposed or implemented to ensure women's retention in workforce.

Qualitative dimension

In Pakistan, the quality of education has a declining trend. Shortage of teachers and poorly equipped laboratories have resulted in the out-dated curriculum that has little relevance to present-day needs. The education is based just on cramming and the students lack professional skills as well as communication skills when they are graduated from an institute. Moreover the universities here are too expensive, due to which the Pakistani students can't afford a university to get higher education. Moreover, the universities here don't provide skills that have a demand in market.[14]

Distance learning

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nation launched an educational television channel, Teleschool.[30] Teleschool is programmed with lessons for kindergarten through high school. Each grade has one hour of course material broadcast per day.[30]

Teleschool instructional videos are in Urdu and English, Pakistan's official languages and the languages used for the country's national curriculum.[30]

The Ministry of Education is also trying to develop instructional programming for radio since Teleschool isn't available to the nation's poorest families.[30]

Achievements

Some of the famous alumni of Pakistan are as follow:

Abdus Salam

Abdus Salam was a Pakistani theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate in physics for his work on the electroweak unification of the electromagnetic and weak forces. Salam, Sheldon Glashow and Steven Weinberg shared the 1979 Nobel prize for this work. Salam holds the distinction of being the first Pakistani to receive the Nobel Prize in any field. Salam heavily contributed to the rise of Pakistani physics to the Physics community in the world.[31][32]

Ayub Ommaya

Ayub Ommaya was a Pakistani neurosurgeon who heavily contributed to his field. Over 150 research papers have been attributed to him. He also invented the Ommaya Reservoir medical procedure. It is a system of delivery of medical drugs for treatment of patients with brain tumours.

Mahbub-ul-Haq

Mahbub-ul-Haq was a Pakistani economist who along with Indian economist Amartya Sen developed the Human Development Index (HDI), the modern international standard for measuring and rating human development.

Atta-ur-Rahman

Atta-ur-Rahman is a Pakistani scientist known for his work in the field of natural product chemistry. He has over 1052 research papers, books and patents attributed to him. He was elected as Fellow of the Royal Society (London) in 2006 [33] and won the UNESCO Science Prize in 1999.[34]

Ismat Beg

Ismat Beg is a Pakistani mathematician famous for his work in fixed point theory, and multicriteria decision making methods. Ismat Beg is Higher Education Commission Distinguished National Professor and an honorary full Professor at the Mathematics Division of the Institute for Basic Research, Florida, USA. He has vast experience of teaching and research. He is a Fellow of Pakistan Academy of Sciences, and Institute of Mathematics and its Applications (U K).

Arfa Abdul Karim Randhawa

Arfa Abdul Karim Randhawa was a Pakistani student and computer prodigy who, in 2004 at the age of nine, became the youngest Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP). She had her name in Guinness Book of World Records.[35] She kept the title until 2008. Arfa represented Pakistan on various international forums including the TechEd Developers Conference. She also received the President's Award for Pride of Performance in 2005. A science park in Lahore, the Arfa Software Technology Park, was named after her.[36][37][38][39] She was invited by Bill Gates to visit Microsoft Headquarters in the United States.[40]

Dr. Naweed Syed

Dr. Naweed Syed is a Pakistani Canadian scientist. He is the first scientist to connect brain cells to a silicon chip.[41][42][43]

Nergis Mavalvala

Nergis Mavalvala is a Pakistani-American astrophysicist known for her role in the first observation of gravitational waves.[44] She was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship in 2010[45][46] and first Lahore technology reward from Information Technology University in 2017.[47][48] Mavalvala is best known for her work on the detection of gravitational waves in the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) project.[44][49][50]

Muhammad Irfan-Maqsood

Muhammad Irfan-Maqsood is a Pakistani researcher and entrepreneur well known in Pakistan, Iran and Turkey for his work in PakistanInfo, KarafarinShow, Genes&Cells and iMaQPress. He is known for his work in the field of Techno-entrepreneurship and Biotechnology.[51] [52][53][54][55][56] He holds PhD in Cell and Molecular Biology and holding two MSc (Biotechnology) and MA (Political Sciences-IR). He has been awarded 4 time Iranian national techno-entrepreneurship award Sheikh Bahai by Minister of Science and Research, Iran and Young Entrepreneur from the Deputy Minister for Youth Affairs.[57] [58] He also has been Joint Secretary of Pakistan Muslim League N Lahore on the instruction of Mian Nawaz Sharif.

Education expenditure as percentage of GDP

The expenditure on education is around 2% of Pakistan's GDP.[59] However, in 2009 the government approved the new national education policy, which stipulates that education expenditure will be increased to 7% of GDP,[60] an idea that was first suggested by the Punjab government.[61]

The author of an article, the history of education spending in Pakistan since 1972, argues that this policy target raises a fundamental question: What extraordinary things are going to happen that would enable Pakistan to achieve within six years what it has been unable to lay a hand on in the past six decades? The policy document is blank on this question and does not discuss the assumptions that form the basis of this target. Calculations of the author show that during the past 37 years, the highest public expenditure on education was 2.80 percent of GDP in 1987-88. Public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP was actually reduced in 16 years and maintained in 5 years between 1972–73 and 2008-09. Thus, out of total 37 years since 1972, public expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP either decreased or remained stagnant for 21 years. The author argues if linear trend were maintained since 1972, Pakistan could have touched 4 percent of GDP well before 2015. However, it is unlikely to happen because the levels of spending have had remained significantly unpredictable and unsteady in the past. Given this disappointing trajectory, increasing public expenditure on education to 7 percent of GDP would be nothing less than a miracle but it is not going to be of godly nature. Instead, it is going to be the one of political nature because it has to be "invented" by those who are at the helm of affairs. The author suggests that little success can be made unless Pakistan adopts an "unconventional" approach to education. That is to say, education sector should be treated as a special sector by immunizing budgetary allocations for it from fiscal stresses and political and economic instabilities. Allocations for education should not be affected by squeezed fiscal space or surge in military expenditure or debts. At the same time, there is a need to debate others options about how Pakistan can "invent" the miracle of raising education expenditure to 7 percent of GDP by 2015.[62]

University rankings

According to the Quality Standard World University Ranking for 2014, QAU, IST, PIEAS, AKU, NUST, LUMS, CUI, KU and UET Lahore are ranked among top 300 universities in Asia.[63]

Religion and education

Education in Pakistan is heavily influenced by religion. For instance, one study of Pakistani science teachers showed that many rejected evolution based on religious grounds.[64] However, most of the Pakistani teachers who responded to the study (14 out of 18) either accepted or considered the possibility of the evolution of living organisms, although nearly all Pakistani science teachers rejected human evolution because they believed that ‘human beings did not evolve from monkeys.’ This is a major misconception and incorrect interpretation of the science of evolution, but according to the study it is a common one among many Pakistani teachers. Although many of the teachers rejected the evolution of humans, " all agreed that there is ‘no contradiction between science and Islam’ in general".[64]

According to the Pakistan’s National Council for Justice and Peace (NCJP) report 2001 on literacy of religious minorities in Pakistan– the average literacy rate among Christians in Punjab is 34 percent, Hindu (upper caste) is 34 percent, Hindu (scheduled castes) is 19 percent ,others (including Parsis, Sikhs,Buddhists and nomads) is 17 percent compared to the national average of 46.56 percent.Whereas the Ahmadis have literacy rate slightly higher than the national average.[65]

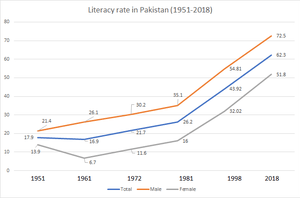

Literacy rate

The definition of literacy has been undergoing changes, with the result that the literacy figure has vacillated irregularly during the last censuses and surveys. A summary is as follows:[66]

| Year of census or survey[66] | Total[66] | Male[66] | Female[66] | Urban[67] | Rural[67] | Definition of being "literate"[66] | Age group[67] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 (West Pakistan) | 17.9%[68] | 21.4%[68] | 13.9%[68] | N/A | N/A | One who can read a clear print in any language | All Ages |

| 1961 (West Pakistan) | 16.9%[68] | 26.1%[68] | 6.7%[68] | 34.8% | 10.6% | One who is able to read with understanding a simple letter in any language | Age 5 and above |

| 1972 | 21.7% | 30.2% | 11.6% | 41.5% | 14.3% | One who is able to read and write in some language with understanding | Age 10 and Above |

| 1981 | 26.2% | 35.1% | 16.0% | 47.1% | 17.3% | One who can read newspaper and write a simple letter | Age 10 and Above |

| 1998 | 43.92% | 54.81% | 32.02% | 63.08% | 33.64% | One who can read a newspaper and write a simple letter, in any language | Age 10 and Above |

| 2018[1] | 62.3% | 72.5% | 51.8% | 76.6% | 53.3% | “Ability to read and understand simple text in any language from a newspaper or magazine, write a simple letter and perform basic mathematical calculation (ie, counting and addition/subtraction).”[69] | Age 10 and Above |

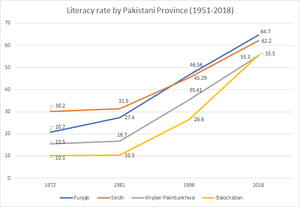

Literacy rate by Province

| Province | Literacy rate[66] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | 1981 | 1998 | 2018[1] | ||

| Punjab | 20.7% | 27.4% | 46.56% | 64.7% | |

| Sindh | 30.2% | 31.5% | 45.29% | 62.2% | |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 15.5% | 16.7% | 35.41% | 55.3% | |

| Balochistan | 10.1% | 10.3% | 26.6% | 55.5% | |

The Economic Survey of Pakistan 2019 report says that literacy rate has increased in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from 54.1% to 55.3%, in Punjab from 61.9% to 64.7% and in Balochistan from 54.3% to 55.5%.In Sindh, the literacy rate has decreased from 63.0% to 62.2%.[70]

Literacy rate of Federally Administered Areas

| Region | Literacy Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 1998 | Latest | |

| Islamabad (ICT) | 47.8%[71][72] | 72.40%[71] | 85% (2015)[6] |

| Azad Jammu & Kashmir (AJK) | 25.7%[73] | 55%[74] | 74% (2017)[8] |

| Gilgit-Baltistan | 3% (female)[75] | 37.85%[75] | N/A |

Mean Years of Schooling in Pakistan by administrative unit

| Unit[76] | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2012 | 2015 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azad Jammu & Kashmir | 3.78 | 4.59 |

5.42 |

7.47 |

7.22 |

7.15 |

6.92 |

6.51 |

| Balochistan | 1.77 | 2.15 |

2.53 |

3.49 |

3.25 |

3.14 |

3.17 |

3.10 |

| FATA | 1.42 | 1.73 |

2.04 |

2.81 |

2.71 |

2.69 |

2.60 |

2.45 |

| Gilgit-Baltistan | 2.01 | 2.44 |

2.88 |

3.97 |

3.84 |

3.80 |

4.59 |

5.17 |

| Islamabad (ICT) | 4.16 | 5.05 |

5.96 |

8.21 |

9.67 |

10.70 |

9.62 |

8.34 |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 1.83 | 2.22 |

2.62 |

3.62 |

3.80 |

3.97 |

3.95 |

3.82 |

| Punjab | 1.96 | 2.38 |

2.81 |

3.88 |

4.44 |

4.85 |

5.23 |

5.41 |

| Sindh | 2.43 | 2.95 |

3.48 |

4.79 |

5.19 |

5.51 |

5.35 |

5.05 |

| Pakistan | 2.28 | 2.77 |

3.27 |

4.51 |

4.68 |

4.85 |

5.09 |

5.16 |

International education

As of January 2015, the International Schools Consultancy (ISC)[77] listed Pakistan as having 439 international schools.[78] ISC defines an 'international school' in the following terms "ISC includes an international school if the school delivers a curriculum to any combination of pre-school, primary or secondary students, wholly or partly in English outside an English-speaking country, or if a school in a country where English is one of the official languages, offers an English-medium curriculum other than the country's national curriculum and is international in its orientation."[78] This definition is used by publications including The Economist.[79]

See also

- List of administrative units of Pakistan by Human Development Index

- List of special education institutions in Pakistan

- Lists of educational institutions in Pakistan

- Pakistan studies

- Pakistani textbooks controversy

- Right to Education Pakistan, an advocacy campaign

- Catholic Board of Education, Pakistan

References

- "Pakistan Economic Survey 2018-19 Chapter 10: Education" (PDF). Economic Survey of Pakistan. 2019-06-10. Retrieved 2019-07-07.

- "Ministry of Education, Pakistan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-02.

- "Constitution of Pakistan Artikel 25A (English translation)" (PDF). na.gov.pk. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- "Education System in Pakistan Problems, Issues & Solutions". pgc.edu. 17 November 2017. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- Peter Blood, ed. (1994). "[Pakistan - EDUCATION]". Pakistan: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 April 2010.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Pakistan Social And Living Standards Measurement Survey (PSLM) 2014-15 Provincial / District" (PDF). March 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-16. Retrieved 2010-09-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dr Pervez Tahir. "Education spending in AJK". The Express Tribune.

- InpaperMagazine (28 February 2011). "Towards e-learning".

- "Literacy Rate in Pakistan Province Wise | Pakistan Literacy Rate". Ilm.com.pk. 2010-09-28. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Education".

- Stuteville, Sarah (August 16, 2009). "seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/localnews/2009670134_pakistanschool16.html". The Seattle Times.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. "Adjusted net enrolment ratio in primary education". UNESCO. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- Rasool Memon, Ghulam (2007). "Education in Pakistan: The Key Issues, Problems and The New Challenges" (PDF). Journal of Management and Social Sciences. 3 (1): 47–55. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- "Vocational education in Pakistan". UNESCO-UNEVOC. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- Global Education Digest 2009 (PDF). UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2009.

- Archived September 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- TAVERNISE, SABRINA (May 3, 2009). "Pakistan's Islamic Schools Fill Void, but Fuel Militancy". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- "Youth and skills: putting education to work, EFA global monitoringthereport, 2012; 2013" (PDF). p. 196. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- Khan, Tasnim; Khan, Rana Ejaz Ali (2004). "Gender Disparity in Education - Extents, Trends and Factors" (PDF). Journal of Research (Faculty of Languages & Islamic Studies). Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- Zakaria, Rafia (2013-07-26). "The doctor brides". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "Are Pakistan's female medical students to be doctors or wives?". BBC News. 2015-08-28. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "Pakistan sees high rate of female medical students, but few doctors". Women in the World in Association with The New York Times - WITW. 2015-08-30. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "Is there a doctor in the house? In Pakistan, quite possibly". The National. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "The PMDC Quota Rule: A Boon or a Bane for Pakistan's Healthcare Future? | JPMS Medical Blogs". Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- Abid, Abdul Majeed (2014-10-22). "Female doctors becoming 'trophy' wives: Is quota the right move?". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "Asma Javaid, etc. vs. Government of Punjab, etc" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- "Controlling the Entry of Male and Female Students in Medical and Dental Colleges". Shaikh Ahmad Hassan School of Law. 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2017-08-17.

- "A Doctor in the House: Balancing Work and Care in the Life of Women Doctors in Pakistan - ProQuest". ProQuest 1897020389. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - George, Susannah. "In the world's fifth most populous country, distance learning is a single television channel". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Ishfaq Ahmad (1998-11-21). "CERN and Pakistan: a personal perspective". CERN Courier. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- Riazuddin (1998-11-21). "Pakistan Physics Centre". ICTP. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "Atta-Ur Rahman | Royal Society". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- "Google Groups". groups.google.com. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- "Arfa Karim in Guinness Book". Tribune.com.pk. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "Software Technology Park name changed to Arfa Software Technology Park". The News (newspaper). 16 January 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2012. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- "9-year-old earns accolade as Microsoft pro". Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- "Remembering a remarkable girl who made a mark on Microsoft". 30 December 2011. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- "Arfa Karim Pakistan's Pride". Zartsh Pakistan. 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2019-09-15.

- In smarts, she's a perfect 10 – Seattle Pi.

- University of Calgary: Naweed Syed

- Carolyn Abraham (August 9, 2010). "Calgary scientists to create human 'neurochip'". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- Kaul, R. Alexander; Syed, Naweed I.; Fromherz, Peter (2004). "Neuron-Semiconductor Chip with Chemical Synapse between Identified Neurons". Physical Review Letters. 92 (3): 038102. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92c8102K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.038102. PMID 14753914.

- "Gravitational wave researcher succeeds by being herself". ScienceMag - AAAS. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Nergis Mavalvala - MacArthur Foundation". MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Nergis Mavalvala and Five Exceptional Stories Of Women In STEM". AutoStraddle. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "Nergis first recipient of Lahore Technology Award". The Nation. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- "ITU convocation: MIT's Nergis Mavalvala given Lahore Technology Award - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2017-12-18. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- "MIT Kavli Institute Directory - MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Making waves". The Hindu. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "An entrepreneurial and creative child is the cornerstone of society". Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- "knowcancer سرطان را بشناسیم توسط دکتر محمد عرفان مقصود". آپارات - سرویس اشتراک ویدیو (in Persian). Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- https://www.KarafarinShow.com

- https://www.pakistaninfo.com

- "Dr. Muhammad Irfan-Maqsood, Founder of GnC has been awarded as young entrepreneur 2018". Genes and cells. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- https://www.imaqpress.com

- "Selecting a Pakistani young man as the top international entrepreneur in the international community". Tasnim news. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- "طراحان كسب و كار- بخش آزاد". istt.ir. Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- "No improvement witnessed in utilisation of education budgets". The News. 28 April 2016.

- Khawar Ghumman. "Education to be allocated seven pc of GDP". Archived from the original on September 12, 2009.

- Archived September 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- Mazhar Siraj (4 July 2010). "Increasing Education Expenditure to 7 percent of GDP in Pakistan: Eyes on the Miracle". Business Recorder. Islamabad.

- "QS University Rankings: Asia 2014". Retrieved 2015-05-28.

- Asghar, A. (2013) Canadian and Pakistani Muslim teachers’ perceptions of evolutionary science and evolution education.Evolution: Education and Outreach 2013, 6:10

- "Religious Minorities in Pakistan By Dr Iftikhar H.Malik" (PDF). Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Pakistan: where and who are the world's illiterates?; Background paper for the Education for all global monitoring report 2006: literacy for life; 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- "Literacy trends in Pakistan; 2004" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- "Copy of Statistical Profile2.cdr" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- "Govt redefines literacy for count - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- "All provinces outshine Sindh in literacy rate". Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Pakistan". CENSUS. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Inequality in the Literacy Levels in Pakistan: Existence and Changes Overtime" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-11-06.

- "AJK literacy rate 1981 census - Google Search". 1988. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Human Rights Watch: "With Friends Like These..." - Human Rights Watch - Google Books. Retrieved 2013-12-10.

- "Mean years schooling - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- "International School Consultancy Group > Home".

- "International School Consultancy Group > Information > ISC News". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- "The new local". The Economist. 17 December 2014.

Further reading

- Halai, Anjum (Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development). "Gender and Mathematics Education: Lessons from Pakistan" (Archive).

- K.K. Aziz. (2004) The Murder of History : A Critique of History Textbooks used in Pakistan. Vanguard. ISBN 969-402-126-X

- Nayyar, A. H. & Salim, Ahmad. (2003) The Subtle Subversion: The State of Curricula and Text-books in Pakistan - Urdu, English, Social Studies and Civics. Sustainable Development Policy Institute. The Subtle Subversion

- Pervez Hoodbhoy and A. H. Nayyar. Rewriting the history of Pakistan, in Islam, Politics and the state: The Pakistan Experience, Ed. Mohammad Asghar Khan, Zed Books, London, 1985.

- Mubarak Ali. In the Shadow of history, Nigarshat, Lahore; History on Trial, Fiction House, Lahore, 1999; Tareekh Aur Nisabi Kutub, Fiction House, Lahore, 2003.

- Rubina Saigol. Knowledge and Identity - Articulation of Gender in Educational Discourse in Pakistan, ASR, Lahore 1995

- Tariq Rahman, Denizens of Alien Worlds: A Study of Education, Inequality and Polarization in Pakistan Karachi, Oxford University Press, 2004. Reprint. 2006

- Tariq Rahman, Language, Ideology and Power: Language learning among the Muslims of Pakistan and North India Karachi, Oxford UP, 2002.

- Tariq Rahman, Language and Politics in Pakistan Karachi: Oxford UP, 1996. Rept. several times. see 2006 edition.

- World Bank Case Study on Primary Education in Pakistan

External links

- World Data on Education, IBE (2011) - overview of Pakistan's education system

- TVET in Pakistan, UNESCO-UNEVOC(2013) - overview of the technical and vocational education system in Pakistan

- "Pakistan ruined by language myth" - Zubeida Mustafa

- Education Updates and result Announcement in Pakistan - Education