Early childhood education

Early childhood education (ECE; also nursery education) is a branch of education theory that relates to the teaching of children (formally and informally) from birth up to the age of eight.[1] Traditionally, this is up to the equivalent of third grade.[2] ECE emerged as a field of study during the Enlightenment, particularly in European countries with high literacy rates.[3] It continued to grow through the nineteenth century as universal primary education became a norm in the Western world. In recent years, early childhood education has become a prevalent public policy issue, as municipal, state, and federal lawmakers consider funding for preschool and pre-K.[4][5][6] It is described as an important period in a child's development. It refers to the development of a child's personality. ECE is also a professional designation earned through a post-secondary education program. For example, in Ontario, Canada, the designations ECE (Early Childhood Educator) and RECE (Registered Early Childhood Educator) may only be used by registered members of the College of Early Childhood Educators, which is made up of accredited child care professionals who are held accountable to the College's standards of practice.[7]

| Caring for children |

|---|

| At home |

| Outside the home |

| Educational settings |

| Institutions and standards |

| Related |

History

The history of early childhood care and education (ECCE) refers to the development of care and education of children from birth through eight years old throughout history.[1] ECCE has a global scope, and caring for and educating young children has always been an integral part of human societies. Arrangements for fulfilling these societal roles have evolved over time and remain varied across cultures, often reflecting family and community structures as well as the social and economic roles of women and men.[8] Historically, such arrangements have largely been informal, involving family, household and community members. After a 20th-century characterized by constant change, including a monumental campaign urging for greater women's rights, women were motivated to pursue a college education and join the workforce. Nevertheless, mothers still face the same challenges as the generations that preceded them on how to care for young children while away at work. The formalization of these arrangements emerged in the nineteenth century with the establishment of kindergartens for educational purposes and day nurseries for care in much of Europe and North America, Brazil, China, India, Jamaica and Mexico.[9][10][11][12]

Context

While the first two years of a child's life are spent in the creation of a child's first "sense of self", most children are able to differentiate between themselves and others by their second year. This differentiation is crucial to the child's ability to determine how they should function in relation to other people.[13] Parents can be seen as a child's first teacher and therefore an integral part of the early learning process.[14]

Early childhood attachment processes that occur during early childhood years 0–2 years of age, can be influential to future education. With proper guidance and exploration children begin to become more comfortable with their environment, if they have that steady relationship to guide them. Parents who are consistent with response times, and emotions will properly make this attachment early on. If this attachment is not made, there can be detrimental effects on the child in their future relationships and independence. There are proper techniques that parents and caregivers can use to establish these relationships, which will in turn allow children to be more comfortable exploring their environment.[15][16] This provides experimental research on the emphasis on caregiving effecting attachment. Education for young students can help them excel academically and socially. With exposure and organized lesson plans children can learn anything they want to. The tools they learn to use during these beginning years will provide lifelong benefits to their success. Developmentally, having structure and freedom, children are able to reach their full potential.

Teaching certification

Teachers seeking to be early childhood educators must obtain certification, among other requirements. "An early childhood education certification denotes that a teacher has met a set of standards that shows they understand the best ways to educate young students aged 3 to 8."[17] There are early childhood education programs across the United States that have a certification that is pre-K to grade 3. There are also programs now that have a duel certification in pre-K to grade 3 and special education from pre-K to grade 8.[18] Other certifications are urban tracks in pre-k to grade 3 that have an emphasis on urban schools and preparing teachers to teach in those school environments. These tracks typically take four years to complete and in the end, provide students with their certifications to teach in schools. These tracks give students in the field experience in multiple different types of classrooms as they learn how to become teachers. An example of a school that has these tracks is Indiana University of Pennsylvania.[19]

Early childhood educators must have knowledge in the developmental changes during early childhood and the subjects being taught in an early childhood classroom.[17] These subjects include language arts and reading, mathematics, and some social studies and science.[17] Early childhood educators must also be able to manage classroom behavior. Positive reinforcement is one popular method for managing behavior in young children.[17] Teacher certification laws vary by state in the United States. In Connecticut, for example, these requirements include a bachelor's degree, 36 hours of special education courses, passing scores on the Praxis II Examination and Connecticut Foundations of Reading Test and a criminal history background check.[20]

For State of Early Childhood Education Bornfreund, 2011; Kauerz, 2010 says that the teacher education and certification requirements do not manifest the research about how to best support development and learning for children in kindergarten through third grade. States are requiring educators who work in open pre-kindergarten to have specific preparation in early childhood education. As per the State of Pre-School Yearbook (Barnett et al., 2015), 45 states require their educators to have a specialization in early childhood education, and 30 states require no less than a bachelor's qualification. As indicated by NAEYC state profiles (NAEYC, 2014), just 14 states require kindergarten instructors to be confirmed in early youth; in the rest of the states, kindergarten educators might be authorized in basic training. Fewer states require ECE affirmation for first-grade educators (Fields and Mitchell, 2007).[21]

Learning through play

Early childhood education often focuses on learning through play, based on the research and philosophy of Jean Piaget, which posits that play meets the physical, intellectual, language, emotional, and social needs (PILES) of children. Children's curiosity and imagination naturally evoke learning when unfettered. Learning through play will allow a child to develop cognitively.[22] This is the earliest form of collaboration among children. In this, children learn through their interactions with others. Thus, children learn more efficiently and gain more knowledge through activities such as dramatic play, art, and social games.[23]

Tassoni suggests that "some play opportunities will develop specific individual areas of development, but many will develop several areas."[24] Thus, it is important that practitioners promote children's development through play by using various types of play on a daily basis. Allowing children to help get snacks ready helps develop math skills (one-to-one ratio, patterns, etc.), leadership, and communication.[25] Key guidelines for creating a play-based learning environment include providing a safe space, correct supervision, and culturally aware, trained teachers who are knowledgeable about the Early Years Foundation.

Davy states that the British Children's Act of 1989 links to play-work as the act works with play workers and sets the standards for the setting such as security, quality and staff ratios.[26] Learning through play has been seen regularly in practice as the most versatile way a child can learn. Margaret McMillan (1860-1931) suggested that children should be given free school meals, fruit and milk, and plenty of exercise to keep them physically and emotionally healthy. Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925) believed that play time allows children to talk, socially interact, use their imagination and intellectual skills. Maria Montessori (1870-1952) believed that children learn through movement and their senses and after doing an activity using their senses. The benefits of being active for young children include physical benefits (healthy weight, bone strength, cardiovascular fitness), stress relief, improved social skills and improved sleep.[27] When young students have group play time it also helps them to be more empathetic towards each other.[28]

In a more contemporary approach, organizations such as the National Association of the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) promote child-guided learning experiences, individualized learning, and developmentally appropriate learning as tenets of early childhood education.[29] A study by the Ohio State University also analyzed the effects of implementing board games in elementary classrooms. This study found that implementing board games in the classroom "helped students develop social skills that transferred to other areas."[30] Specific outcomes included students being more helpful, cooperative and thoughtful with other students. Negative outcomes included children feeling excluded and showing frustration with game rules.

Piaget provides an explanation for why learning through play is such a crucial aspect of learning as a child. However, due to the advancement of technology, the art of play has started to dissolve and has transformed into "playing" through technology. Greenfield, quoted by the author, Stuart Wolpert, in the article "Is Technology Producing a Decline in Critical Thinking and Analysis?", states, "No media is good for everything. If we want to develop a variety of skills, we need a balanced media diet. Each medium has costs and benefits in terms of what skills each develops." Technology is beginning to invade the art of play and a balance needs to be found.[31]

Many oppose the theory of learning through play because they think children are not gaining new knowledge. In reality, play is the first way children learn to make sense of the world at a young age. Research suggests that the way children play and interact with concepts at a young age could help explain the differences in social and cognitive interactions later. When learning what behavior to associate with a set action can help lead children on to a more capable future.[32] As children watch adults interact around them, they pick up on their slight nuances, from facial expressions to their tone of voice. They are exploring different roles, learning how things work, and learning to communicate and work with others. These things cannot be taught by a standard curriculum, but have to be developed through the method of play. Many preschools understand the importance of play and have designed their curriculum around that to allow children to have more freedom. Once these basics are learned at a young age, it sets children up for success throughout their schooling and their life.

Many say that those who succeed in kindergarten know when and how to control their impulses. They can follow through when a task is difficult and listen to directions for a few minutes. These skills are linked to self-control, which is within the social and emotional development that is learned over time through play among other things.

Theories of child development

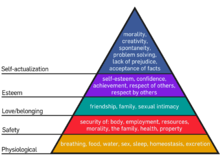

The Developmental Interaction Approach is based on the theories of Jean Piaget, Erik Erikson, John Dewey, and Lucy Sprague Mitchell. The approach focuses on learning through discovery.[33] Jean Jacques Rousseau recommended that teachers should exploit individual children's interests in order to make sure each child obtains the information most essential to his personal and individual development.[34] The five developmental domains of childhood development include:[35] To meet those developmental domains, a child has a set of needs that must be met for learning. Maslow's hierarchy of needs showcases the different levels of needs that must be met the chart to the right showcases these needs.[36]

- Physical: the way in which a child develops biological and physical functions, including eyesight and motor skills

- Social: the way in which a child interacts with others[37] Children develop an understanding of their responsibilities and rights as members of families and communities, as well as an ability to relate to and work with others.[38]

- Emotional: the way in which a child creates emotional connections and develops self-confidence. Emotional connections develop when children relate to other people and share feelings.

- Language: the way in which a child communicates, including how they present their feelings and emotions, both to other people and to themselves. At 3 months, children employ different cries for different needs. At 6 months they can recognize and imitate the basic sounds of spoken language. In the first 3 years, children need to be exposed to communication with others in order to pick up language. "Normal" language development is measured by the rate of vocabulary acquisition.[39]

- Cognitive skills: the way in which a child organizes information. Cognitive skills include problem solving, creativity, imagination and memory.[40] They embody the way in which children make sense of the world. Piaget believed that children exhibit prominent differences in their thought patterns as they move through the stages of cognitive development: sensorimotor period, the pre-operational period, and the operational period.[41]

Vygotsky’s socio-cultural learning theory

Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky proposed a "socio-cultural learning theory" that emphasized the impact of social and cultural experiences on individual thinking and the development of mental processes.[42] Vygotsky's theory emerged in the 1930s and is still discussed today as a means of improving and reforming educational practices. In Vygotsky's theories of learning, he also postulated the theory of the zone of proximal development. This theory ties in with children building off prior knowledge and gaining new knowledge related to skills they already have. In the theory it describes how new knowledge or skills are taken in if they are not fully learned but are starting to emerge. A teacher or older friend lends support to a child learning a skill, be it building a block castle, tying a shoe, or writing one's name. As the child becomes more capable of the steps of the activity, the adult or older child withdraws supports gradually, until the child is competent completing the process on his/her own. This is done within that activity's zone—the distance between where the child is, and where he potentially will be.[43] In each zone of proximal development, they build on skills and grow by learning more skills in their proximal development range. They build on the skills by being guided by teachers and parents. They must build from where they are in their zone of proximal development.[44]

Vygotsky argued that since cognition occurs within a social context, our social experiences shape our ways of thinking about and interpreting the world.[45] People such as parents, grandparents, and teachers play the roles of what Vygotsky described as knowledgeable and competent adults. Although Vygotsky predated social constructivists, he is commonly classified as one. Social constructivists believe that an individual's cognitive system is a resditional learning time. Vygotsky advocated that teachers facilitate rather than direct student learning.[46] Teachers should provide a learning environment where students can explore and develop their learning without direct instruction. His approach calls for teachers to incorporate students’ needs and interests. It is important to do this because students' levels of interest and abilities will vary and there needs to be differentiation.

However, teachers can enhance understandings and learning for students. Vygotsky states that by sharing meanings that are relevant to the children's environment, adults promote cognitive development as well. Their teachings can influence thought processes and perspectives of students when they are in new and similar environments. Since Vygotsky promotes more facilitation in children's learning, he suggests that knowledgeable people (and adults in particular), can also enhance knowledges through cooperative meaning-making with students in their learning.[47] Vygotsky's approach encourages guided participation and student exploration with support. Teachers can help students achieve their cognitive development levels through consistent and regular interactions of collaborative knowledge-making learning processes.

Piaget’s constructivist theory

Jean Piaget's constructivist theory gained influence in the 1970s and '80s. Although Piaget himself was primarily interested in a descriptive psychology of cognitive development, he also laid the groundwork for a constructivist theory of learning.[48] Piaget believed that learning comes from within: children construct their own knowledge of the world through experience and subsequent reflection. He said that "if logic itself is created rather than being inborn, it follows that the first task of education is to form reasoning." Within Piaget's framework, teachers should guide children in acquiring their own knowledge rather than simply transferring knowledge.[49]

According to Piaget's theory, when young children encounter new information, they attempt to accommodate and assimilate it into their existing understanding of the world. Accommodation involves adapting mental schemas and representations in order to make them consistent with reality. Assimilation involves fitting new information into their pre-existing schemas. Through these two processes, young children learn by equilibrating their mental representations with reality. They also learn from mistakes.[50]

A Piagetian approach emphasizes experiential education; in school, experiences become more hands-on and concrete as students explore through trial and error.[51] Thus, crucial components of early childhood education include exploration, manipulating objects, and experiencing new environments. Subsequent reflection on these experiences is equally important.[52]

Piaget's concept of reflective abstraction was particularly influential in mathematical education.[53] Through reflective abstraction, children construct more advanced cognitive structures out of the simpler ones they already possess. This allows children to develop mathematical constructs that cannot be learned through equilibration — making sense of experiences through assimilation and accommodation — alone.[54]

According to Piagetian theory, language and symbolic representation is preceded by the development of corresponding mental representations. Research shows that the level of reflective abstraction achieved by young children was found to limit the degree to which they could represent physical quantities with written numerals. Piaget held that children can invent their own procedures for the four arithmetical operations, without being taught any conventional rules.[55]

Piaget's theory implies that computers can be a great educational tool for young children when used to support the design and construction of their projects. McCarrick and Xiaoming found that computer play is consistent with this theory.[56] However, Plowman and Stephen found that the effectiveness of computers is limited in the preschool environment; their results indicate that computers are only effective when directed by the teacher.[57] This suggests, according to the constructivist theory, that the role of preschool teachers is critical in successfully adopting computers as they existed in 2003.[58]

Kolb's experiential learning theory

David Kolb's experiential learning theory, which was influenced by John Dewey, Kurt Lewin and Jean Piaget, argues that children need to experience things in order to learn: "The process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience. Knowledge results from the combinations of grasping and transforming experience." The experimental learning theory is distinctive in that children are seen and taught as individuals. As a child explores and observes, teachers ask the child probing questions. The child can then adapt prior knowledge to learning new information.

Kolb breaks down this learning cycle into four stages: concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation, and active experimentation. Children observe new situations, think about the situation, make meaning of the situation, then test that meaning in the world around them.[59]

Practical implications of early childhood education

In recent decades, studies have shown that early childhood education is critical in preparing children to enter and succeed in the (grade school) classroom, diminishing their risk of social-emotional mental health problems and increasing their self-sufficiency later in their lives.[60] In other words, the child needs to be taught to rationalize everything and to be open to interpretations and critical thinking. There is no subject to be considered taboo, starting with the most basic knowledge of the world he lives in, and ending with deeper areas, such as morality, religion and science. Visual stimulus and response time as early as 3 months can be an indicator of verbal and performance IQ at age 4 years.[61] When parents value ECE and its importance their children generally have a higher rate of attendance. This allows children the opportunity to build and nurture trusting relationships with educators and social relationships with peers.

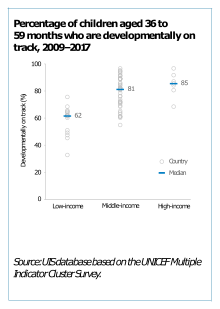

By providing education in a child's most formative years, ECE also has the capacity to pre-emptively begin closing the educational achievement gap between low and high-income students before formal schooling begins.[62] Children of low socioeconomic status (SES) often begin school already behind their higher SES peers; on average, by the time they are three, children with high SES have three times the number of words in their vocabularies as children with low SES.[63] Participation in ECE, however, has been proven to increase high school graduation rates, improve performance on standardized tests, and reduce both grade repetition and the number of children placed in special education.[64]

Especially since the first wave of results from the Perry Preschool Project were published, there has been widespread consensus that the quality of early childhood education programs correlate with gains in low-income children's IQs and test scores, decreased grade retention, and lower special education rates.

Several studies have reported that children enrolled in ECE increase their IQ scores by 4-11 points by age five, while a Milwaukee study reported a 25-point gain.[65] In addition, students who had been enrolled in the Abecedarian Project, an often-cited ECE study, scored significantly higher on reading and math tests by age fifteen than comparable students who had not participated in early childhood programs.[66] In addition, 36% of students in the Abecedarian Preschool Study treatment group would later enroll in four-year colleges compared to 14% of those in the control group.[66]

In 2017, researchers reported that children who participate in ECE graduate high school at significantly greater rates than those who do not. Additionally, those who participate in ECE require special education and must repeat a grade at significantly lower rates than their peers who did not receive ECE.[67] The NIH asserts that ECE leads to higher test scores for students from preschool through age 21, improved grades in math and reading, and stronger odds that students will keep going to school and attend college.[68]

Nathaniel Hendren and Ben Sprung-Keyser, two Harvard economists, found high Marginal Values of Public Funds (MVPFs) for investments in programs supporting the health and early education of children, particularly those that reach children from low-income families. The average MVPF for these types of initiatives is over 5, while the MVPFs for programs for adults generally range from 0.5 to 2.[69]

Beyond benefitting societal good, ECE also significantly impacts the socioeconomic outcomes of individuals. For example, by age 26, students who had been enrolled in Chicago Child-Parent Centers were less likely to be arrested, abuse drugs, and receive food stamps; they were more likely to have high school diplomas, health insurance and full-time employment.[70] Studies also show that ECE heightens social engagement, bolsters lifelong health, reduces the incidence of teen pregnancy, supports mental health, decreases the risk of heart disease, and lengthens lifespans.[71]

The World Bank's 2019 World Development Report on The Changing Nature of Work[72] identifies early childhood development programs as one of the most effective ways governments can equip children with the skills they will need to succeed in future labor markets.

According to a 2020 study in the Journal of Political Economy by Clemson University economist Jorge Luis García, Nobel laureate James J. Heckman and University of Southern California economists Duncan Ermini Leaf and María José Prados, every dollar spent on a high-qulaity early-childhood programs led to a return of $7.3 over the long-term.[73]

The Perry Preschool Project

The Perry Preschool Project, which was conducted in the 1960s in Ypsilanti, Michigan, is the oldest social experiment in the field of early childhood education and has heavily influenced policy in the United States and across the globe.[74] The experiment enrolled 128 three- and four-year-old African-American children with cognitive disadvantage from low-income families, who were then randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. The intervention for children in the treatment group included active learning preschool sessions on weekdays for 2.5 hours per day. The intervention also included weekly visits by the teachers to the homes of the children for about 1.5 hours per visit to improve parent-child interactions at home.[75]

Initial evaluations of the Perry intervention showed that the preschool program failed to significantly boost an IQ measure. However, later evaluations that followed up the participants for more than fifty years have demonstrated the long-term economic benefits of the program, even after accounting for the small sample size of the experiment, flaws in its randomization procedure, and sample attrition.[76] There is substantial evidence of large treatment effects on the criminal convictions of male participants, especially for violent crime, and their earnings in middle adulthood. Research points to improvements in non-cognitive skills, executive functioning, childhood home environment, and parental attachment as potential sources of the observed long-term impacts of the program. The intervention's many benefits also include improvements in late-midlife health for both male and female participants.[76]

Research also demonstrates spillover effects of the Perry program on the children and siblings of the original participants. A study concludes, "The children of treated participants have fewer school suspensions, higher levels of education and employment, and lower levels of participation in crime, compared with the children of untreated participants. Impacts are especially pronounced for the children of male participants. These treatment effects are associated with improved childhood home environments."[77] The study also documents beneficial impacts on the male siblings of the original participants. Evidence from the Perry Preschool Project is noteworthy because it advocates for public spending on early childhood programs as an economic investment in a society's future, rather than in the interest of social justice.[78]

Early childhood education policy in the United States

During World War II, the US implemented a large, well-funded childcare system in order to help mothers join the workforce to support the war effort. The system supported families of all incomes, and the government paid approximately two-thirds of the costs, with parents covering the rest (at a rate of about $9 or $10 a day in today's dollars). These programs were very popular, and research demonstrates that, in addition to helping families during the war, adults who participated in the system as children were employed at greater rates, earned more money, and were less liable to require cash assistance than their peers who did not participate. Children from low-income families realized these positive effects of participation even more than their better-off peers.[79]

In the past decade, there has been a national push for state and federal policy to address the early years as a key component of public education. At the federal level, the Obama administration made the Race to the Top Early Learning Challenge a key tenet of their education reform initiative, awarding $500 million to states with comprehensive early childhood education plans.[80] According to the United States Department of Education, this program focuses on "improving early learning and development programs for young children by supporting States' efforts to: (1) increase the number and percentage of low-income and disadvantaged children in each age group of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers who are enrolled in high-quality early learning programs; (2) design and implement an integrated system of high-quality early learning programs and services; and (3) ensure that any use of assessments conforms with the recommendations of the National Research Council's reports on early childhood."[81] In addition, a largely Democratic contingent sponsored the Strong Start for America's Children Act in 2013, which provides free early childhood education for low-income families.[82] Specifically, the Act would generate the impetus and support for states to expand ECE; provide funding through formula grants and Title II (Learning Quality Partnerships), III (Child Care) and IV (Maternal, Infant and Home Visiting) funds; and hold participating states accountable for Head Start early learning standards.[83]

Head Start grants are awarded directly to public or private non-profit organizations, including community-based and faith-based organizations, or for-profit agencies within a community that wish to compete for funds. The same categories of organizations are eligible to apply for Early Head Start, except that applicants need not be from the community they will be serving.[84]

Many states have created new early childhood education agencies. Massachusetts was the first state to create a consolidated department focused on early childhood learning and care. Just in the past fiscal year, state funding for public In Minnesota, the state government created an Early Learning scholarship program, where families with young children meeting free and reduced price lunch requirements for kindergarten can receive scholarships to attend ECE programs.[85] In California, Senator Darrell Steinberg led a coalition to pass the Kindergarten Readiness Act, which creates a state early childhood system supporting children from birth to age five and provides access to ECE for all 4-year-olds in the state. It also created an Early Childhood Office charged with creating an ECE curriculum that would be aligned with the K-12 continuum.[86]

States have created legislation regarding early childhood education. In California, for example, the Kindergarten Readiness Act of 2010 changed the required birthday for admittance to kindergarten and first grade, and established a transitional kindergarten program.[87]

State funding for pre-K increased by $363.6 million to a total of $5.6 billion, a 6.9% increase from 2012 to 2013. 40 states fund pre-K programs.[88]

Currently, one of America's larger challenges regarding ECE is a dearth in workforce, partly due to low compensation for rigorous work. The average early childhood teaching assistant earns an annual salary of $10,500, while the highest-paid early childhood educators earn an average of $18,000 per year. The turnover of ECE staff averages 31% per year.[89] Another challenge is to ensure the quality of ECE programs. Because ECE is a relatively new field, there is little research and consensus into what makes a good program. However, the National Association of the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) is a national organization that has identified evidence-based ECE standards and accredits quality programs.[90] Continuing the leadership role it established with the Common Core, the federal government could play a key role in establishing ECE standards for states.

The American legal system has also played a hand in public ECE. State adequacy cases can also create a powerful legal impetus for states to provide universal access to ECE, drawing upon the rich research illustrating that by the time they enter school, students from low-income backgrounds are already far behind other students. The New Jersey case Abbott County School District v. Burke and South Carolina case Abbeville County School District v. State established early but incomplete precedents in looking at "adequate education" as education that addresses needs best identified in early childhood, including immediate and continuous literacy interventions.

In the 1998 case of Abbott v. Burke (Abbott V), the New Jersey Supreme Court required New Jersey's poorest school districts to implement high-quality ECE programs and full day kindergarten for all three and four-year-olds. Beyond ruling that New Jersey needed to allocate more funds to preschools in low-income communities in order to reach "educational adequacy," the Supreme court also authorized the state department of education to cooperate "with… existing early childhood and daycare programs in the community" to implement universal access.[91]

In the 2005 case of Abbeville v. State, the South Carolina Supreme Court decided that ECE programs were necessary to break the "debilitating and destructive cycle of poverty for low-income students and poor academic achievement." Besides mandating that all low-income children have access to ECE by age three, the court also held that early childhood interventions—such as counseling, special needs identification, and socio-emotional supports—continue through grade three (Abbeville, 2005). The court furthermore argued that ECE was not only imperative for educational adequacy but also that "the dollars spent in early childhood intervention are the most effective expenditures in the educational process."[92]

The 2019 budget approved by President Donald Trump included a 21 percent cut in Department of Health and Human Services funding.[93] This is where most early education and care programs like Head Start[94] are included. The department's budget highlights doing away with the pre-school development grant program, which aided 18 states in spreading out access to pre-K for 4-year-old children during the last few years. It helped said states in improving overall quality of pre-K programs. This program was initiated during the Obama administration because of Every Student Succeeds Act or ESSA under the DHHS.[95]

The federal government called for a minimal increase in Head Start funding with approximately $9.3 billion for said program. This subsidy is estimated to serve around 861,000 kids. However, the administration withdrew the requirement that such program started serving children for a longer day and school year due to insufficient funding.[96] The Center for American Progress said President Trump and the House of Representatives advocated deep cuts in programs that were supposed to help impoverished families rather than attend to the needs of low and middle-income households through paid leave and child care as well as increasing minimum wage.[97]

Unlike other areas of education, early childhood care and education (ECCE) places a strong emphasis on developing the whole child – attending to his or her social, emotional, cognitive, and physical needs – in order to establish a solid and broad foundation for lifelong learning and well-being. "Care" includes health, nutrition, and hygiene in a warm, secure, and nurturing environment, and "education" includes stimulation, socialization, guidance, participation, learning, and developmental activities. ECCE begins at birth and can be organized in a variety of non-formal, formal and informal modalities, such as parenting education, health-based mother and child intervention, care institutions, child-to-child programmes, home-based or centre-based [Child care|childcare], kindergartens and pre-schools. Different terms to describe ECCE are used by different countries, institutions, and stakeholders, such as early childhood development (ECD), early childhood education and care (ECEC), and early childhood care and development (ECCD), with Early Childhood Care and Education as the nomenclature.

As research shows, children's care and educational needs are intertwined. Poor care, health, nutrition, and physical and emotional security can affect educational potentials in the form of mental retardation, impaired cognitive and behavioral capacities, motor development delay, depression, and difficulties with concentration and attention. Inversely, early health and nutrition interventions, such as iron supplementation, deworming treatment and school feeding, have been shown to directly contribute to increased pre-school attendance.[98] Studies have demonstrated better child outcomes through the combined intervention of cognitive stimulation and nutritional supplementation than through either cognitive stimulation or nutritional supplementation alone. Quality ECCE is one that integrates educational activities, nutrition, health care and social services.[99]

Decades of research provide unequivocal evidence that [public investment] in early childhood care and education can produce economic returns equal to roughly 10 times its costs.[100][101] The sources of these gains are (1) childcare that enables mothers to work and (2) education and other supports for child development that increase subsequent school success, labor force productivity, prosocial behavior, and health. The benefits from enhanced child development are the largest part of the economic return, but both are important considerations in policy and program design. The economic consequences include reductions in public and private expenditures associated with school failure, crime, and health problems as well as increases in earnings.[102]

International agreements

The first World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education took place in Moscow from 27 to 29 September 2010, jointly organized by UNESCO and the city of Moscow. The overarching goals of the conference are to:

- Reaffirm ECCE as a right of all children and as the basis for development

- Take stock of the progress of Member States towards achieving the EFA Goal 1

- Identify binding constraints toward making the intended equitable expansion of access to quality ECCE services

- Establish, more concretely, benchmarks and targets for the EFA Goal 1 toward 2015 and beyond

- Identify key enablers that should facilitate Member States to reach the established targets

- Promote global exchange of good practices[103]

According to UNESCO, a preschool curriculum is one that delivers educational content through daily activities and furthers a child's physical, cognitive, and social development. Generally, preschool curricula are only recognized by governments if they are based on academic research and reviewed by peers.[104]

Preschool for Child Rights have pioneered into preschool curricular areas and is contributing into child rights through their preschool curriculum.[105]

Curricula in early childhood care and education

Curricula in early childhood care and education (ECCE) is the driving force behind any ECCE programme. It is ‘an integral part of the engine that, together with the energy and motivation of staff, provides the momentum that makes programmes live’.[106] It follows therefore that the quality of a programme is greatly influenced by the quality of its curriculum. In early childhood, these may be programs for children or parents, including health and nutrition interventions and prenatal programs, as well as center-based programs for children.[107]

Orphan education

A lack of education during the early childhood years for orphans is a worldwide concern. Orphans are at higher risk of "missing out on schooling, living in households with less food security, and suffering from anxiety and depression."[108] Education during these years has the potential to improve a child's "food and nutrition, health care, social welfare, and protection."[108] This crisis is especially prevalent in sub-saharan Africa which has been heavily impacted by the aids epidemic. UNICEF reports that "13.3 million children (0-17 years) worldwide have lost one or both parents to AIDS. Nearly 12 million of these children live in sub-Saharan Africa."[108] Government policies such as the Free Basic Education Policy have worked to provide education for orphan children in this area, but the quality and inclusiveness of this policy has brought criticism.[109]

Barriers and challenges

Children's learning potential and outcomes are negatively affected by exposure to violence, abuse and child labour. Thus, protecting young children from violence and exploitation is part of broad educational concerns. Due to difficulties and sensitivities around the issue of measuring and monitoring child protection violations and gaps in defining, collecting and analysing appropriate indicators,[110] data coverage in this area is scant. However, proxy indicators can be used to assess the situation. For example, ratification of relevant international conventions indicates countries’ commitment to child protection. By April 2014, 194 countries had ratified the CRC3; and 179 had ratified the 1999 International Labour Organization's Convention (No. 182) concerning the elimination of the worst forms of child labour. However, many of these ratifications are yet to be given full effect through actual implementation of concrete measures. Globally, 150 million children aged 5–14 are estimated to be engaged in child labour.[110] In conflict-affected poor countries, children are twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday compared to those in other poor countries.[111] In industrialized countries, 4 per cent of children are physically abused each year and 10 per cent are neglected or psychologically abused.[110][112]

In both developed and developing countries, children of the poor and the disadvantaged remain the least served. This exclusion persists against the evidence that the added value of early childhood care and education services are higher for them than for their more affluent counterparts, even when such services are of modest quality. While the problem is more intractable in developing countries, the developed world still does not equitably provide quality early childhood care and education services for all its children. In many European countries, children, mostly from low-income and immigrant families, do not have access to good quality early childhood care and education.[113][112]

Notable early childhood educators

- Fred Rogers

- Charles Eugene Beatty

- Friedrich Fröbel

- Elizabeth Harrison

- David P. Weikart

- Juan Sánchez Muliterno, President of The World Association of Early Childhood Educators

See also

- Baby video

- Bright from the Start

- Compensatory education

- Head Start Program

- Men in early childhood education

- Montessori education

- Playwork

- Preschool curriculum

- Primary education

- Reggio Emilia approach

- Pretend play

- Waldorf education

References

Citations

- "National Association for the Education of Young Children". About Us. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- "Best Accredited Online Early Childhood Education Degrees of 2018". Teacher Certification Degrees. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Eddy, Matthew Daniel (2016). "The Child Writer: Graphic Literacy and the Scottish Educational System, 1700–1820" (PDF). History of Education. 46 (6): 695–718. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2016.1197971.

- "Early Learning from Birth through Third Grade". National Governor's Association.

- "Why Cities Are Making Preschool Education Available to All Children". Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "Pre-K Funding from State and Federal Sources". 25 April 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "College of Early Childhood Educators". College of Early Childhood Educators.

- UNESCO (2006). EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007: Strong Foundations - Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO.

- Kamerman, S. B. 2006. A global history of early childhood education and care. Background paper for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007.

- Jones, J.; Brown, A.; Brown, J. (2011). Caring and Learning Together: A Case Study of Jamaica (PDF). UNESCO Early Childhood and Family Policy Series, No. 21. Paris, UNESCO.

- Nunes, F.; Corsino, P.; Didonet, V. (2010). Caring and Learning Together: A Case Study of Brazil (PDF). UNESCO Early Childhood and Family Policy Series No. 19. Paris, UNESCO.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- Oatley, Keith; Keltner, Dacher; Jenkins, Jennifer M (2007). Understanding emotions (2nd ed.). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. p. 211. ISBN 978-1-4051-3103-2.

- Footnote Anning, A and Cullen, J. and Fleer, M. (2004) Early childhood education. London: SAGE.

- "The Scope of Early Childhood Education". 20 July 2010. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Academic Journal

- "Early Childhood Teaching Certification | Early Childhood Certification". teaching-certification.com. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "EARLY CHILDHOOD/SPECIAL EDUCATION, BSED". www.iup.edu/pse/undergrad/early-childhood-special-education-bsed/. 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Early Childhood/Special Education Urban Track, BSEd - Undergraduate Programs - Professional Studies in Education - IUP". iup.edu. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- "Connecticut Teaching Certification | Become a teacher in CT". teaching-certification.com. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- Hooper, Alison (3 October 2018). "The influence of early childhood teacher certification on kindergarten and first-grade students' academic outcomes". Early Child Development and Care. 188 (10): 1419–1430. doi:10.1080/03004430.2016.1263623. ISSN 0300-4430.

- "Earlychildhood NEWS - Article Reading Center". earlychildhoodnews.com. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- Winner, Melinda (28 January 2009). "The Serious Need for Play". Scientific American.

- Tassoni, P. (2000) S/NVQ 3 play work. London: Heinemann Educational.

- McGee, M. (2005). Hidden Mathematics in the Preschool Classroom. Teaching Children Mathematics, 11(6), 345-347.

- Annie Davy (November 2000). Playwork: Play and Care for Children 5-15. Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-1-86152-666-3.

- "Physical Activity". healthykids.nsw.gov.au. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "Benefits Of Play - Learning Activities In Early Childhood - Parenting For Brain". Parenting For Brain. 18 December 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Glossary of Early Childhood Terms - National Association for the Education of Young Children - NAEYC TYC - Teaching Young Children Magazine". naeyc.org. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014.

- Bendixen-Noe, Mary. "Bringing Play Back to the Classroom: How Teachers Implement Board and Card Games Based on Academic Learning Standards" (PDF) – via The Ohio State University.

- Wolpert, Stuart. "Is Technology Producing a Decline in Critical Thinking and Analysis?" UCLA Newsroom. UCLA, 27 Jan. 2009. Web. 5 Feb. 2015.

- https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/features/education-and-the-brain-what-happens-when-children-learn

- Shapiro, E.; Nager, N. (1999). "The Developmental-Interaction Approach to Education: Retrospect and Prospect". Occasional Paper Series. 1999 (1). Bank Street College of Education. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

"Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach". State of New Jersey Department of Education. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011.

Casper, V; Theilheimer, R (2009). Introduction to early childhood education: Learning together. New York: McGraw-Hill. - McDowall Clark, R (2013). Childhood in Society . London: Learning Matters.

- Jonathan Doherty; Malcolm Hughes (2009). Child Development: Theory and Practice 0-11. Addison-Wesley, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-4058-2127-8.

- Jones, Denisha (8 March 2019). "APPLYING MASLOW TO SCHOOLS: A NEW APPROACH TO SCHOOL EQUITY". Defending the Early Years.

- Jeffrey Trawick-Smith (2014). Early Childhood Development: A Multicultural Perspective. Pearson Education, Limited. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-13-335277-1.

- "[ARCHIVED CONTENT] Spiritual, moral, social and cultural development - Schools". nationalarchives.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013.

- NIH (2011) Speech and language development milestones, USA: NIDCD: (accessed 15 April 2014).

- Sally Neaum (17 May 2013). Child Development for Early Years Students and Practitioners. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4462-6753-0.

- Doherty, J. and Hughes, M. (2009). Child development: theory and practice 0-11. Harlow: Longman.

- Vygotsky, Lev S. (1978). Cole, Michael; John-Steiner, Vera; Scribner, Sylvia; Souberman, Ellen (eds.). Mind in Society: the Development of Higher Psychological Processes.

- "Zone of Proximal Development - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- Mohammad, Khatib (December 2010). "Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development: Instructional Implications and Teachers' Professional Development" (PDF). English Language Teaching: 12.

- Jaramillo 1996.

- Jaramillo, J (1996). "Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory and Contributions to the Development of Constructivist Curricula". Education. 117 (1): 133–140.

- McDevitt, T.M. & Ormrod, J.E. (2016). Cognitive Development: Piaget and Vygotsky. In Child Development and Education. (pp. 196-235). Pearson.

- Smith, L (1985). "Making Educational Sense of Piaget's Psychology". Oxford Review of Education. 11 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1080/0305498850110205.

- "Jean Piaget: Champion of children's ideas". Scholastic Early Childhood Today. 15 (5): 43. 2001.

- Piaget, J (1997). "Development and Learning". Readings on the Development of Children: 7–20.

- "Jean Piaget: Champion of Children's Ideas". Scholastic Early Childhood Today. 15 (5): 43. 2001.

- "Constructivism as a Paradigm for Teaching and Learning". Thirteen | Ed Online. Educational Broadcasting Corporation. 2004.

- Kato; Kamii, Ozaki, Nagahiro (2002). "Young Children's Representations of Groups of Objects: The Relationship Between Abstraction and Representation". Journal for Research and Mathematics Education. 33 (1): 30–45. doi:10.2307/749868. JSTOR 749868.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Simon; Tzur, Heinz, Kinzel (2004). "Explicating a mechanism for conceptual learning' elaborating the construct of reflective abstraction". Journal for Research and Mathematics Education. 35 (5): 305–329. doi:10.2307/30034818. JSTOR 30034818.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kamii; Ewing (1996). "Basing teaching on Piaget's constructivism". Childhood Education. 72 (5): 260. doi:10.1080/00094056.1996.10521862.

- McCarrick; Xiaoming (2007). "Buried treasure: the impact of computer use on young children's social, cognitive, language development and motivation". AACE Journal. 15 (1): 73–95.

- Plowman; Stephen (2003). "A 'beginning addition'? Research on ICT and preschool children". Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 19 (2): 149–164. doi:10.1046/j.0266-4909.2003.00016.x. hdl:1893/459.

- Towns (2010). "Computer education and computer use by preschool educators". ProQuest 365702854. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "David Kolb". Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- Connecticut Office of Early Childhood Planning, 2013

- Dougherty and Haith of the University of Denver, "Infant Expectations and Reaction Time as Predictors of Childhood Speed of Processing and IQ", published in volume 33 (1997) of the journal Developmental Psychology.

- Coleman, J. S., Campbell, E. Q., Hobson, C. J., McPartland, J., Mood, A. M., Weinfeld, F. D., & York, R. L. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity: Summary report (Vol. 2). US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education.

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. If a parent values the benefits of ECE, then they are more likely to have higher attendance, which aids children in forming meaningful relationships with their educators and peers. Paul H Brookes Publishing.

- Schweinhart, L.J., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., Barnett, W.S., Belfield, C.R., and Nores, M. (2005). Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool study through age 40. Ypsilanti: High/Scope Press, 2005.

- Barnett, W. S. (1995). Long-term effects of early childhood programs on cognitive and school outcomes. The future of children, 25-50.

- Campbell, F. A., Ramey, C. T., Pungello, E., Sparling, J., & Miller-Johnson, S. (2002). Early childhood education: Young adult outcomes from the Abecedarian Project. Applied Developmental Science, 6(1), 42-57.

- McCoy, Dana Charles; Yoshikawa, Hirokazu; Ziol-Guest, Kathleen M.; Duncan, Greg J.; Schindler, Holly S.; Magnuson, Katherine; Yang, Rui; Koepp, Andrew; Shonkoff, Jack P. (2017). "Impacts of Early Childhood Education on Medium- and Long-term Educational Outcomes". Educational Researcher. 46 (8): 474–497. doi:10.3102/0013189X17737739. PMC 6107077. PMID 30147124.

- "Why Is Early Learning Important?". National Institutes of Health: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. National Institutes of Health.

- Hendren, Nathaniel; Sprung-Keyser, Ben (2019). "A Unified Welfare Analysis of Government Policies" (PDF). Working Paper.

- Heckman, 2013

- Sneha Elango; Jorge Luis García; James J. Heckman; Andrés Hojman (2016). "Early Childhood Education" (PDF). In Moffitt, Robert A. (ed.). Economics of Means-Tested Programs in the United States (Volume 2 ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 235–297. and "Why Is Early Learning Important?". National Institutes of Health: Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. National Institutes of Health.

- World Bank World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work.

- García, Jorge Luis; Heckman, James J.; Leaf, Duncan Ermini; Prados, María José (2 August 2019). "Quantifying the Life-Cycle Benefits of an Influential Early-Childhood Program". Journal of Political Economy: 000. doi:10.1086/705718. ISSN 0022-3808.

- Council of Economic Advisers (2015). "The economics of early childhood investments" (PDF). Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Schweinhart, L. J., J. Montie, Z. Xiang, W. S. Barnett, C. R. Belfield, and M. Nores (2005). Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool Study through age 40 (Monographs of the High/Scope Educational Research Foundation, 14). Ypsilanti, MI: High Scope Educational Research Foundation.

- Heckman, James J; Karapakula, Ganesh (2019). "The Perry Preschoolers at Late Midlife: A Study in Design-Specific Inference" – via National Bureau of Economic Research. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Heckman, James J; Karapakula, Ganesh (2019). "Intergenerational and Intragenerational Externalities of the Perry Preschool Project" – via National Bureau of Economic Research. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - here Slate article: Waldfogel, Joel. "Teach Your Children Well: The economic case for preschool based on working paper: James J. Heckman, Dimitriy V. Masterov. "The Productivity Argument for Investing in Young Children." NBER Working Paper No. 13016, Issued in April 2007." Slate Online, Posted Friday, 25 May 2007, accessed 30 May 2007

- Kurtz, Dayna M. (23 July 2018). "We Have a Child-Care Crisis in This Country. We Had the Solution 78 Years Ago". The Washington Post.

- "Race to the Top -- Early Learning Challenge". ed.gov. November 2018.

- "Race to the Top -- Early Learning Challenge". www2.ed.gov. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- "The Strong Start for America's Children Act of 2013 (H.R. 3461)". house.gov. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014.

- Children’s Defense Fund, 2014

- "Office of Head Start". 2 October 2015.

- Minnesota Department of Education, 2013

- "Senate Bill 837: An Act to Expand Transitional Kindergarten".

- "Transitional Kindergarten in California." CSU Center for the Advancement of Reading, California State University, Apr. 2011.

- Workman, E., Griffith, M. & Atchison, B (2014). State Pre-K Funding – 2013-14 Fiscal Year. Education Commission of the States.

- National Association of the Education of Young Children, 2014

- National Association of the Education of Young Children, 2013

- "Abbott v. Burke (Abott V), 153 N.J. 480. (1998)" (PDF).

- "Abbeville County School District v. State, 515 S.C. 535 (1999)".

- "Democrats.org". Democrats.org. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Head Start Programs". Office of Head Start | ACF. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) | U.S. Department of Education". ed.gov. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Implications for PreK-12 Education in Trump's New Budget". New America. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "The Trump Plan to Cut Benefit Programs Threatens Children - Center for American Progress". Center for American Progress. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- UNESCO. 2006. EFA Global Monitoring Report 2007: Strong Foundations - Early Childhood Care and Education. Paris, UNESCO.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- Barnett, W. S., and Masse, L. N. 2007. Early childhood programme design and economic returns: Comparative bene t-cost analysis of the Abecedarian programme and policy implications. Economics of Education Review, 26, pp. 113-125.

- Engle, P. L., Fernald, L. C. H., Alderman, H., Behrman, J., O’Gara, C., Yousafzai, A., Cabral de Mello, M., Hidrobo, M., Ulkuer, N., Ertem, I., Iltus, S., and the Global Development Steering group. 2011. Strategies for reducing inequalities and improving developmental outcomes for young children in low-income and middle-income countries. e Lancet, 37, pp. 1339-1353.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- "World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education, Moscow (Russia), 27-29 September 2010".

- "UNESCO: Preschool Curricula" (PDF). UNESCO. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- "Preschool for Child Rights".

- Epstein, A, Larner, M and Halpern, R. 1995. A Guide to Developing Community-Based Family Support Programs. Ypsilanti, Michigan, High/Scope Press.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 243–265. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- Jepkemboi, Grace; Jolly, Pauline; Gillyard, KaNesha; Lissanu, Lydia (September 2016). "Educating Orphaned and Vulnerable Children in Elgeyo-Marakwet County, Kenya". Childhood Education. 92 (5): 391–395. doi:10.1080/00094056.2016.1226114. ISSN 0009-4056. PMC 5383207. PMID 28392577.

- Robson, Sue; Kanyanta, Sylvester Bonaventure (July 2007). "Moving towards inclusive education policies and practices? Basic education for AIDS orphans and other vulnerable children in Zambia". International Journal of Inclusive Education. 11 (4): 417–430. doi:10.1080/13603110701391386. ISSN 1360-3116.

- UNICEF. 2013. State of the World’s Children. Children with Disabilities. New York, UNICEF.

- UNESCO. 2010. The World Conference on Early Childhood Care and Education: Building the Wealth of Nations - Concept Paper.

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- Eurydice. 2009. Tackling Social and Cultural Inequalities through Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe. Brussels, Eurydice.

Sources

- Neaum, S. (2013). Child development for early years students and practitioners. 2nd Edition. London: Sage Publications.

- Learning Journey, Inspire Early. "Inspire ELJ New Child Care Preston | Montessori | Reggio Emilia".

External links

| Library resources about Early childhood education |

- "Early Childhood Care and Education". UNESCO. Archived from the original on 7 November 2010.

- "World Organization for Early Childhood Education (OMEP)".

- "National Institute for Early Education Research".

- "Early Childhood Education". National Education Association.

- "Heckman Equation for Investing in Early Human Development".