American Indian boarding schools

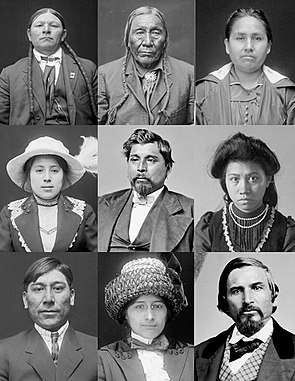

Native American boarding schools, also known as Indian Residential Schools, were established in the United States during the late 19th and mid 20th centuries with a primary objective of assimilating Native American children and youth into Euro-American culture, while at the same time providing a basic education in Euro-American subject matters. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations, who often started schools on reservations,[1] especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. The government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the last residential schools closing as late as 1973. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) founded additional boarding schools based on the assimilation model of the off-reservation Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Children were typically immersed in European-American culture through forced changes that removed indigenous cultural signifiers. These methods included being forced to have European-American style haircuts, being forbidden to speak their Indigenous languages, and having their real names replaced by European names to both "civilize" and "Christianize" them.[2] (Similarly, Evenk children were required to speak Russian when sent to boarding schools in the former Soviet Union.[3]) The experience of the schools was usually harsh and sometimes deadly, especially for the younger children who were forcibly separated from their families. The children were forced to abandon their Native American identities and cultures.[2] Investigations of the later twentieth century have revealed many documented[4] cases of sexual, manual, physical and mental abuse occurring mostly in church-run[5] schools. In summarizing the recent scholarship from Native perspectives, Dr. Julie Davis argues:

Perhaps the most fundamental conclusion that emerges from boarding school histories is the profound complexity of their historical legacy for Indian people's lives. The diversity among boarding school students in terms of age, personality, family situation, and cultural background created a range of experiences, attitudes, and responses. Boarding schools embodied both victimization and agency for Native people and they served as sites of both cultural loss and cultural persistence. These institutions, intended to assimilate Native people into mainstream society and eradicate Native cultures, became integral components of American Indian identities and eventually fueled the drive for political and cultural self-determination in the late 20th century.[6]

Since those years, tribal nations have increasingly insisted on community-based schools and have also founded numerous tribal colleges and universities. Community schools have also been supported by the federal government through the BIA and legislation. The largest boarding schools have closed. By 2007, most of the schools had been closed down and the number of Native American children in boarding schools had declined to 9,500. During this same period, more Native Americans moved to urban environments accommodating in varying degrees and manners to majority culture.

History of education of Native Americans

How different would be the sensation of a philosophic mind to reflect that instead of exterminating a part of the human race by our modes of population that we had persevered through all difficulties and at last had imparted our Knowledge of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the source of future life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America – This opinion is probably more convenient than just.

— Henry Knox to George Washington, 1790s.[7]

In the late eighteenth century, reformers starting with Washington and Knox,[8] in efforts to "civilize" or otherwise assimilate Native Americans (as opposed to relegating them to reservations), adopted the practice of assimilating Native American children in current American culture, which was at the time largely based on rural agriculture, with some small towns and few large cities. The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 promoted this civilization policy by providing funding to societies (mostly religious) who worked on Native American education, often at schools established in or near Native American communities.

Moses Tom sent his children to an Indian boarding school.[9]

I rejoice, brothers, to hear you propose to become cultivators of the earth for the maintenance of your families. Be assured you will support them better and with less labor, by raising stock and bread, and by spinning and weaving clothes, than by hunting. A little land cultivated, and a little labor, will procure more provisions than the most successful hunt; and a woman will clothe more by spinning and weaving, than a man by hunting. Compared with you, we are but as of yesterday in this land. Yet see how much more we have multiplied by industry, and the exercise of that reason which you possess in common with us. Follow then our example, brethren, and we will aid you with great pleasure ...

— President Thomas Jefferson, Brothers of the Choctaw Nation, December 17, 1803[10]

One fact that many may not be aware of is the fact that Native Americans had a good education system before being forced to attend boarding schools. They even had one of the first women's colleges.[11]

Non-reservation boarding schools

In 1634, Fr. Andrew White of the Society of Jesus established a mission in what is now the state of Maryland, and the purpose of the mission, stated through an interpreter to the chief of a Native American tribe there, was "to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven."[12] The mission's annual records report that by 1640, they had founded a community they named St. Mary's, and Native Americans were sending their children there "to be educated among the English",[13] including the daughter of the Pascatoe chief Tayac. This was either a school for girls, or an early co-ed school. The same records report that in 1677, "a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of Maryland, directed by two of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, made good progress. Maryland and the recently established school sent two boys to St. Omer who yielded in abilities to few Europeans, when competing for the honour of being first in their class. So that not gold, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth alone, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher state of virtue and cultivation."[14]

Harvard College had an "Indian College" on its campus in the mid-1600s, supported by the English Society for Propagation of the Gospel. Its few Native American students came from New England, at a time when higher education was very limited for all classes and colleges were more similar to today's high schools. In 1665, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, "from the Wampanoag...did graduate from Harvard, the first Indian to do so in the colonial period".[15] In early years, other Indian schools were created by local communities, as with the Indian school in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1769, which gradually developed into Dartmouth College. Other schools were created in the East, where Indian reservations were less common than they became in the late nineteenth century in western states.

West of the Mississippi, schools near indigenous settlements and on reservations were first founded by religious missionaries, who believed they could extend education and Christianity to Native Americans. Some of their efforts were part of the progressive movement after the Civil War. As Native Americans were forced onto reservations following the Indian Wars, missionaries founded additional schools with boarding facilities, as children were enrolled very far from their communities and were not permitted to travel home or receive parental visitation.

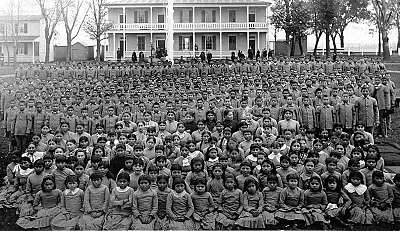

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded by the Civil War Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt in 1879 at a former military installation, became a model for others established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Carlisle Indian Industrial School forced assimilation to Christian culture and lose their Native American traditions, as demonstrated by their motto, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man.” Pratt said in a speech in 1892, "A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead."[16] Comanche Chief Tosahwi is reported to have had an exchange with Philip Sheridan where Sheridan purportedly stated "The only good Indians I ever saw were dead", which was sometimes rephrased as "the only good Indian is a dead Indian."[17] In Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Dee Brown attributed the quote to Sheridan, stating that "Lieutenant Charles Nordstrom, who was present, remembered the words and passed them on, until in time they were honed into an American aphorism: The only good Indian is a dead Indian.[18] While Sheridan later denied making either statement,[17] biographer Roy Morris Jr. states that, nevertheless, popular history credits Sheridan with saying "The only good Indian is a dead Indian." This variation "has been used by friends and enemies ever since to characterize and castigate his Indian-fighting career."[19]

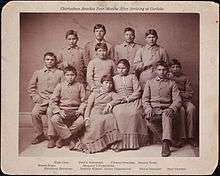

Pratt professed "assimilation through total immersion."[16] He conducted a "social experiment" on Apache prisoners of war at a fort in Florida.[20] He cut their long hair, put them in uniforms, forced them to learn English, and subjected them to strict military protocols.[20] He had arranged for the education of some of the young Native American men at the Hampton Institute, now a historically black college, after he had supervised them as prisoners at a fort in Florida. Hampton Institute was established in the 1870s and in its original form, created a formal education program for Native Americans in 1875 at the end of the American Indian Wars. The United States Army sent seventy-two warriors from the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche and Caddo Nations, to imprisonment and exile in St. Augustine, Florida. Essentially they were considered hostages to persuade their peoples in the West to keep peace. From this funding Hampton was able to grow into a university, though over time the student population shifted to African-American students.

At the prison, he tried to inculcate Native Americans with Anglo-American culture, while giving them some leeway to govern themselves. As at the Hampton Institute, he included in the Carlisle curriculum vocational training for boys and domestic science for girls, including chores around the school and producing goods for market. They also produced a newspaper,[21] had a well-regarded chorus and orchestra, and developed sports programs. The vocational training reflected the administration's understanding of skills needed at most reservations, which were located in rural areas, and reflected a society still based on agriculture. In the summer students often lived with local farm families and townspeople, reinforcing their assimilation, and providing labor at low cost to the families.

Carlisle and its curriculum became the model for the Bureau of Indian Affairs; by 1902 there were 25 federally funded non-reservation schools in 15 states and territories, with a total enrollment of over 6,000 students. Federal legislation required Native American children to be educated according to Anglo-American settler-colonial standards. Parents had to authorize their children's attendance at boarding schools, and if they refused officials could use coercion to gain a quota of students from any given reservation.[22]

As the model of boarding schools was adopted more widely by the US government, many Native American children were separated from their families and tribes when they were sent or sometimes taken to boarding schools far from their home reservations. These schools ranged from those similar to the federal Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which became a model for BIA-run schools, to the many schools sponsored by religious denominations.

In this period, when students arrived at boarding schools their lives altered dramatically. They were given short haircuts (a source of shame for boys of many tribes), uniforms, and English names; sometimes these were based on their own, other times they were assigned at random. They were not allowed to speak their own languages, even between each other, and they were forced to attend church services and convert to Christianity. Discipline was stiff in many schools, and it often included chores, solitary confinement and corporal punishment including beatings with sticks, rulers and belts.[20]

The following is a quote from Anna Moore regarding the Phoenix Indian School:

If we were not finished [scrubbing the dining room floors] when the 8 a.m. whistle sounded, the dining room matron would go around strapping us while we were still on our hands and knees.[23]

Legality

In 1891,[24] the government issued a “compulsory attendance” law that enabled federal officers to forcibly take Native American children from their home and reservation. The American government believed they were rescuing these children from a world of poverty and depression and teaching them "life skills". Tabatha Tooney Booth, from the University of Oklahoma wrote in her paper, Cheaper Than Bullets,

“Many parents had no choice but to send their kids, when Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to withhold rations, clothing, and annuities of those families that refused to send students. Some agents even used reservation police to virtually kidnap youngsters, but experienced difficulties when the Native police officers would resign out of disgust, or when parents taught their kids a special “hide and seek” game. Sometimes resistant fathers found themselves locked up for refusal. In 1895, nineteen men of the Hopi Nation were imprisoned to Alcatraz because they refused to send their children to boarding school.[25]

However, in 1978, the Indian Child Welfare Act gave Native American parents the legal right to deny their child's placement in the school. Damning evidence against the morality of Non-Reservation boarding schools contributed to the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Congress approved of this act in 1978 after first-hand accounts of life in Native American boarding schools. National Indian Child Welfare Association explains,

At the time, not only was ICWA vitally needed, but it was crafted to address some of the most longstanding and egregious removal practices specifically targeting Native children. Among its added protections for Native children, ICWA requires caseworkers to make several considerations when handling an ICWA case, including:

- Providing active efforts to the family;

- Identifying a placement that fits under the ICWA preference provisions;

- Notifying the child’s tribe and the child’s parents of the child custody proceeding; and

- Working actively to involve the child’s tribe and the child’s parents in the proceedings.[26]

Meriam Report of 1928

In 1926, the Department of the Interior (DOI) commissioned the Brookings Institution to conduct a survey of the overall conditions of the American Indians and to assess federal programs and policies. The Meriam Report, officially titled The Problem of Indian Administration, was submitted February 21, 1928, to the Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work. Related to education of Native American children, it recommended that the government:

- Abolish The Uniform Course of Study, which taught only European-American cultural values;

- Educate younger children at community schools near home, and have older children attend non-reservation schools for higher grade work;

- Have the Indian Service (now Bureau of Indian Affairs) provide American Indians the education and skills they need to adapt both in their own communities and United States society.

Despite the Meriam Report, attendance in Indian boarding schools generally grew throughout the first half of the 20th century and doubled in the 1960s.[23] Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children are estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding school.[23][27] The rise of pan-Indian activism, tribal nations' continuing complaints about the schools, and studies in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (such as the Kennedy Report and the National Study of American Indian Education) led to passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This emphasized decentralization of students from boarding schools to community schools. As a result, many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. By 2007, 9,500 American Indian children were living in Indian boarding school dormitories.[16] This figure includes those in 45 on-reservation boarding schools, seven off-reservation boarding schools, and 14 peripheral dormitories.[16] From 1879 to the present day, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Native Americans as children attended Indian boarding schools.[28]

Today, a few off-reservation boarding schools still operate, but funding for them is in decline.

Disease and death

Throughout non-reservation boarding schools, students became easily susceptible to diseases, like trachoma, tuberculosis, and measles,[29] and death. The overcrowding of the schools and the unfamiliar environment contributed to the rapid spread of disease within the schools. "An often-underpaid staff provided irregular medical care. And not least, apathetic boarding school officials frequently failed to heed their own directions calling for the segregation of children in poor health from the rest of the student body".[30] Tuberculosis was especially deadly among students. Many children died while in custody at Indian Schools. Often students were prevented from communicating with their families, and parents were not notified when their children fell ill. Many times, children would pass away and the families never knew they were sick. "Many of the Indian deaths during the great influenza pandemic of 1918–19, which hit the Native American population hard, took place in boarding schools." [31] The 1928 Meriam Report noted that infectious disease was often widespread at the schools due to malnutrition, overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and students weakened by overwork. The report said that death rates for Native American students were six and a half times higher than for other ethnic groups.[23] Another report regarding the Phoenix Indian school stated, "In December of 1899, measles broke out at the Phoenix Indian School, reaching epidemic proportions by January. In its wake, 325 cases of measles, 60 cases of pneumonia, and 9 deaths were recorded in a 10-day period."[32]"

Implications of assimilation

The U.S. federal government recognized a need for assimilation of diverse people of color; specifically, assimilation of the Native Americans. From 1810 until 1917 the U.S. federal government subsidized the creation of and education within mission and boarding schools.[33]:16 "By 1885, 106 [Indian Schools] had been established, many of them on abandoned military installations" using military personnel and Indian prisoners Native American boarding schools in the United States were seen as the means for the government to achieve assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream American culture. Assimilation efforts included forcibly removing Native Americans from their families, converting them to Christianity, preventing them from learning or practicing indigenous culture and customs, and living in a strict military fashion.

When students arrived at boarding schools, the routine was typically the same. First, the students were stripped of their tribal clothing and their hair was cut. Second, "[t]o instill the necessary discipline, the entire school routine was organized in martial fashion, and every facet of student life followed a strict timetable".[34] Since many military personnel ran the boarding schools, military principles mechanized the daily routines. One student recalled,

A small bell was tapped, and each of the pupils drew a chair from under the table. Supposing this act meant that they were to be seated, I pulled out mine and at once slipped into it from one side. But when I turned my head, I saw that I was the only one seated, and all the rest at our table remained standing. Just as I began to rise, looking shyly around to see how chairs were to be used, a second bell was sounded. All were seated at last, and I had to crawl back into my chair again. I heard a man's voice at one end of the hall, and I looked around to see him. But all the others hung their heads over their plates. As I glanced at the long chain of tables, I cause the eyes of a paleface woman upon me. Immediately I dropped my eyes, wondering why I was so keenly watched by the strange woman. The man ceased his mutterings, and then a third bell was tapped. Everyone picked up his knife and fork and began eating. I began crying instead, for by this time I was afraid to venture anything more.[35]

Besides mealtime routines, administrators 'educated' Indians on how to farm using European-based methods. Some boarding schools worked to become small agrarian societies where the school became its own self-sufficient community.[36]

From the moment students arrived at school, they could not "be Indian" in any way".[33]:19 To aid in their assimilation to U.S. Anglo culture, boarding school administrations "forbade, whether in school or on reservation, tribal singing and dancing, along with the wearing of ceremonial and 'savage' clothes, the practice of native religions, the speaking of tribal languages, the acting out of traditional gender roles".[36]:11 School administrators argued that young women needed to be specifically targeted due to their important place in continuing assimilation education in their future homes. Educational administrators and teachers were instructed that "Indian girls were to be assured that, because their grandmothers did things in a certain way, there was no reason for them to do the same".[34]:282

Reservation schools had been established to help students learn about the dominant European history of the U.S. However, "removal to reservations in the West in the early part of the century and the enactment of the Dawes or General Allotment Act in 1887 eventually took nearly 50 million acres of land from Indian control". On-reservation schools were either taken over by Anglo leadership or destroyed in the process. Indian-controlled school systems became non-existent while "the Indians [were] made captives of federal or mission education".

Although schools used verbal corrective means to enforce assimilation, often more violent measures were used. Archuleta et al. (2000) noted cases where students had "their mouths washed out with lye soap when they spoke their native languages; they could be locked up in the guardhouse with only bread and water for other rule violations; and they faced corporal punishment and other rigid discipline on a daily basis".[33]:42 Beyond physical and mental abuse, some school authorities sexually abused students as well. One former student retold,

Intimidation and fear were very much present in our daily lives. For instance, we would cower from the abusive disciplinary practices of some superiors, such as the one who yanked my cousin's ear hard enough to tear it. After a nine-year-old girl was raped in her dormitory bed during the night, we girls would be so scared that we would jump into each other's bed as soon as the lights went out. The sustained terror in our hearts further tested our endurance, as it was better to suffer with a full bladder and be safe than to walk through the dark, seemingly endless hallway to the bathroom. When we were older, we girls anguished each time we entered the classroom of a certain male teacher who stalked and molested girls.[33]:42[36]

Women taken from their families and placed into boarding schools, such as the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, were moved to accomplish the U.S. federal government's vision of "educating Indian girls in the hope that women trained as good housewives would help their mates assimilate" into U.S. mainstream culture.[37]

Historian Brenda Child asserts that boarding schools cultivated pan-Indian-ism and made possible cross-tribal coalitions that have helped many different tribes collaborate in the 20th century. She argues:

People formerly separated by language, culture, and geography lived and worked together in residential schools. Students formed close bonds and enjoyed a rich cross-cultural change. Graduates of government schools often married former classmates, found employment in the Indian Service, migrated to urban areas, returned to their reservations and entered tribal politics. Countless new alliances, both personal and political, were forged in government boarding schools.[38]

However, this analysis is not widespread amongst boarding school survivors, Native American communities, and particularly within the indigenous resurgence movement.

Jacqueline Emery, introducing an anthology of boarding school writings, suggests that these writings prove that the children showed a cultural and personal resilience "more common among boarding school students than one might think": though the school authorities censored the material, it nonetheless demonstrates multiple methods of resistance to school regimes.[39] Several students educated in boarding schools such as Gertrude Bonnin, Angel De Cora, Francis La Flesche, and Laura Cornelius Kellogg went on to become precursors to modern Indigenous resurgence activists.

After release from Indian boarding schools, students were expected to return to their tribes and induce European assimilation there. Many students who returned to their reservations experienced alienation, language and cultural barriers, and confusion, in addition to the posttraumatic stress disorder and legacy of trauma resulting from abuse received in Indian boarding schools. They struggled to respect elders, but also received resistance from family and friends when trying to initiate Anglo-American changes.[36] Since former students who were visited by faculty were rated as successful by the following criteria: "orderly households, 'citizen's dress', Christian weddings, 'well-kept' babies, land in severalty, children in school, industrious work habits, and leadership roles in promoting the same 'civilized' lifestyles among family and tribe",[36]:39 many students returned to the boarding schools. General Richard Henry Pratt, who was a main administrator, began to recognize that "[t]o civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay."[40]

Economic repercussions

By controlling the environment and perspective of young Native Americans, the American government used non-reservation boarding schools as a cost-benefit alternative to military campaigns against Western Native Americans. The assimilation of young Native American children eliminated a generation of warriors that potentially posed a threat to US military. These schools also found an economic benefit in the children through their labor. Children often were forced to undertake laborious tasks in order to fund employment, and during the summers, children were "leased" to work on farms or in the household for wealthy families. Amnesty International argues, "In addition to bringing in income, the hard labor prepared children to take their place in white society—the only one open to them—on the bottom rung of the socioeconomic ladder.”

List of Native American boarding schools

- Absentee Shawnee Boarding School, near Shawnee, Indian Territory, open 1893–99[41][42]

- Albuquerque Indian School, Albuquerque, New Mexico[43]

- Anadarko Boarding School, Anadarko, Oklahoma, open 1911–33[44]

- Arapaho Manual Labor and Boarding School, Darlington, Indian Territory, opened in 1872 and paid for by federal funds,[45] but run by the Hicksite (Liberal) Friends and Orthodox Quakers.[46] Moved to Concho Indian Boarding School in 1909.[47]

- Armstrong Academy, near Chahta Tamaha, Indian Territory

- Asbury Manual Labor School, near Fort Mitchell, Alabama, open 1822–30[48][49] by the United Methodist Missions.[48]

- Asbury Manual Labor School, near Eufaula, Creek Nation, Indian Territory, open 1850–88 by the United Methodist Missions.[50]

- Bacone College, Muscogee, Oklahoma,[43] 1881–present

- Bloomfield Female Academy, originally near Achille, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory. Opened in 1848 but relocated to Ardmore, Oklahoma, around 1917 and in 1934 was renamed Carter Seminary.[51]

- Bond's Mission School or Montana Industrial School for Indians, run by Unitarians, Crow Indian Reservation, near Custer Station, Montana, 1886–97[52]

- Burney Institute, near Lebanon, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1854–87 when name changed to Chickasaw Orphan Home and Manual Labor School and operated by the Cumberland Presbyterian Church.[53]

- Cameron Institute, Cameron, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1893–early 20th century, was operated by the Presbyterian Church[54]

- Cantonment Indian Boarding School, Canton, Indian Territory, run by the General Conference Mennonites[55] from September, 1882 to 1 July 1927[56]

- Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania,[57] open 1879–1918[58]

- Carter Seminary, Ardmore, Oklahoma, 1917–2004 when the facility moved to Kingston, Oklahoma, and was renamed the Chickasaw Children's Village.[59]

- Chamberlain Indian School, Chamberlain, South Dakota[57]

- Chemawa Indian School, Salem, Oregon[43]

- Cherokee Female Seminary, Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, open 1851–1910[60]

- Cherokee Male Seminary, Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, open 1851–1910[60]

- Cherokee Orphan Asylum, Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, opened in 1871[61]

- Cheyenne-Arapaho Boarding School, Darlington, Indian Territory, opened 1871[46] became the Arapaho Manual Labor and Boarding School in 1879[45]

- Cheyenne Manual Labor and Boarding School, Caddo Springs, Indian Territory, opened 1879 and paid with by federal funds,[45] but run by the Hicksite (Liberal) Friends and Orthodox Quakers.[46] Moved to Concho Indian Boarding School in 1909.[47]

- Chickasaw (male) Academy, near Tishomingo, Chickasaw Nation, Oklahoma. Opened in 1850 by the Methodist Episcopal Church and changed its name to Harley Institute around 1889.[62]

- Chickasaw Children's Village, on Lake Texoma near Kingston, Oklahoma, opened 2004[59]

- Chickasaw National Academy, near Stonewall, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open about 1865 to 1880[63]

- Chickasaw Orphan Home and Manual Labor School (formerly Burney Academy) near Lebanon, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1887–1906[64]

- Chilocco Indian Agricultural School, Chilocco, Oklahoma, open 1884–1980[65]

- Chinle Boarding School, Many Farms, Arizona[57]

- Choctaw Academy, Blue Spring, Scott County, Kentucky, opened 1825

- Chuala Female Seminary (also known as the Pine Ridge Mission School), near Doaksville, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1838–61[66][67] by the Presbyterian Church[66]

- Circle of Nations Indian School , Wahpeton, North Dakota[57]

- Colbert Institute, Perryville, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1852–57 by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South[68]

- Collins Institute, near Stonewall, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open about 1885 to 1905[63]

- Concho Indian Boarding School, Concho, Oklahoma, open 1909–83[69][70]

- Creek Orphan Asylum, Okmulgee, Creek Nation, Indian Territory, opened 1895[71][72]

- Darlington Mission School, Darlington, Indian Territory, run by the General Conference Mennonites from 1881 to 1902[73]

- Dwight Mission, Marble City, Oklahoma[43]

- Elliott Academy (formerly Oak Hill Industrial Academy), near Valliant, Oklahoma, 1912–36[74]

- El Meta Bond College, Minco, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1890–1919[75]

- Emahaka Mission, Wewoka, Seminole Nation, Indian Territory, open 1894–1911[76]

- Euchee Boarding School, Sapulpa, Creek Nation, Indian Territory,[43] open 1894–1947[77]

- Eufaula Dormitory, Eufaula, Oklahoma, name changed from Eufaula High School in 1952.[78] Still in operation[79]

- Eufaula Indian High School, Eufaula, Creek Nation, Indian Territory,[43] replaced the burned Asbury Manual Labor School.[50] Open in 1892[79]–1952, when the name changed to Eufaula Dormitory[78]

- Flandreau Indian School, South Dakota[57]

- Folsom Training School, near Smithville, Oklahoma, open 1921[80]–32, when it became an all-white school[81]

- Fort Bidwell School, Fort Bidwell, California[57]

- Fort Coffee Academy, Fort Coffee, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1840–63 and run by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South[66]

- Fort Shaw Indian School, Fort Shaw, Montana[57]

- Fort Sill Indian School (originally known as Josiah Missionary School), near Fort Sill, Indian Territory, opened in 1871 by the Quakers,[82] remained open until 1980[83]

- Fort Totten Indian Industrial School, Fort Totten, North Dakota. Boarding and Indian Industrial School in 1891–1935. Became a Community and Day School from 1940 to 1959. Now a Historic Site run by the State Historic Society of North Dakota.

- Genoa Indian Industrial School, Genoa, Nebraska

- Goodland Academy & Indian Orphanage, Hugo, Oklahoma[43]

- Greenville School, California[57]

- Hampton Institute, began accepting Native students in 1878.

- Harley Institute, near Tishomingo, Chickasaw Nation, Oklahoma. Prior to 1889 was known as the Chickasaw Academy and was operated by the Methodist Episcopal Church until 1906.[62]

- Haskell Indian Industrial Training School, Lawrence, Kansas, 1884–present[58]

- Hayward Indian School, Hayward, Wisconsin[57]

- Hillside Mission School, near Skiatook, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, open 1884[84]–1908 by the Quakers[85]

- Holbrook Indian School, Holbrook, Arizona[57]

- Ignacio Boarding School, Colorado[57]

- Iowa Mission School, near Fallis, Iowa Reservation, Indian Territory, open 1890–93 by the Quakers[86]

- Intermountain Indian School, Utah

- Jesse Lee Home for Children, Originally in Unalaska, Alaska, moved to Seward, Alaska. Founded and run by Methodist Church

- Jones Academy, Hartshorne, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory/Oklahoma.[43] Opened in 1891[87]

- Koweta Mission School Coweta, Creek Nation, Indian Territory, open 1843–61[88]

- Levering Manual Labor School, Wetumka, Creek Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1882[89]–91, operated by the Southern Baptist Convention.[90]

- Many Farms High School, near Many Farms, Arizona

- Marty Indian School, Marty, South Dakota

- Mary Immaculate School, DeSmet, Idaho 1878-1974

- Mekasukey Academy, near Seminole, Seminole Nation, Indian Territory, open 1891–1930[91]

- Morris Industrial School for Indians, Morris, Minnesota,[92] open 1887–1909

- Mount Edgecumbe High School, Sitka, Alaska, established as a BIA school, now operated by the State of Alaska

- Mount Pleasant Indian Industrial Boarding School, Mount Pleasant, Michigan,[43] 1893–1934

- Murray State School of Agriculture, Tishomingo, Oklahoma,[43] est. 1908

- Nenannezed Boarding School, New Mexico[57]

- New Hope Academy, Fort Coffee, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1844[66]–96[93] and run by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South[66]

- Nuyaka School and Orphanage (Nuyaka Mission, Presbyterian), Okmulgee, Creek Nation, Indian Territory,[43] 1884–1933

- Oak Hill Industrial Academy, near Valliant, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1878[94]–1912 by the Presbyterian Mission Board. The Choctaw freedmen's academy was renamed as the Elliott Academy (aka Alice Lee Elliott Memorial Academy) in 1912.[95]

- Oak Ridge Manual Labor School, near Holdenville, Indian Territory, in the Seminole Nation. Open 1848–60s by the Presbyterian Mission Board.[96]

- Oklahoma Presbyterian College for Girls, Durant, Oklahoma[43]

- Oklahoma School for the Blind, Muskogee, Oklahoma[43]

- Oklahoma School for the Deaf, Sulphur, Oklahoma[43]

- Oneida Indian School, Wisconsin[57]

- Osage Boarding School, Pawhuska, Osage Nation, Indian Territory, open 1874–1922[97]

- Park Hill Mission School, Park Hill, Indian Territory/Oklahoma, opened 1837[98]

- Pawnee Boarding School, Pawnee, Indian Territory, open 1878–1958[99]

- Phoenix Indian School, Phoenix, Arizona[43]

- Pierre Indian School, Pierre, South Dakota[57]

- Pine Ridge Boarding School, Pine Ridge, South Dakota

- Pine Ridge Mission School, near Doaksville, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory; see Chuala Female Seminary

- Pinon Boarding School, Pinon, Arizona[57]

- Pipestone Indian School, Pipestone, Minnesota[57]

- Quapaw Industrial Boarding School, Quapaw Agency, Indian Territory, open 1872–1900[100]

- Rainy Mountain Boarding School, near Gotebo, Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Reservation, Indian Territory, open 1893–1920[101]

- Rapid City Indian School, Rapid City, South Dakota[57]

- Red Moon School, near Hammon, Indian Territory, open 1897–1922[102]

- Rehoboth Mission School located in Rehoboth, New Mexico, near Navajo Nation. Operated as an Indian Boarding School by the Christian Reformed Church in North America from 1903 to 1990s.

- Riverside Indian School, Anadarko, Oklahoma, open 1871–present[103]

- Sac and Fox Boarding School, near Stroud, Indiant Territory, open 1872[104]–1919[105] by the Quakers[104]

- Sacred Heart College, near Asher, Potowatamie Nation, Indian Territory, open 1884–1902[106]

- Sacred Heart Institute, near Asher, Potowatamie Nation, Indian Territory, open 1880–1929[106]

- St. Agnes Academy, Ardmore, Oklahoma[43]

- St. Agnes Mission, Antlers, Oklahoma[43]

- St. Boniface Indian School, Banning, California[107]

- St. Elizabeth's Boarding School, Purcell, Oklahoma[43]

- St. John's Boarding School, Gray Horse, Osage Nation, Indian Territory, open 1888–1913 and operated by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions[108]

- St. Joseph's Boarding School, Chickasha, Oklahoma[43]

- St. Mary's Academy, near Asher, Potowatamie Nation, Indian Territory, open 1880–1946[106]

- St. Louis Industrial School, Pawhuska, Osage Nation, Indian Territory, open 1887–1949 and operated by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions[108]

- St. Mary's Boarding School, Quapaw Agency Indian Territory/Oklahoma, open 1893–1927[109]

- St. Patrick's Mission and Boarding School, Anadarko, Indian Territory, open 1892[110]–1909 by the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions. It was rebuilt and called the Anadarko Boarding School.[44]

- San Juan Boarding School, New Mexico[57]

- Santa Fe Indian School, Santa Fe, New Mexico

- Sasakwa Female Academy, Sasakwa, Seminole Nation, Indian Territory, open 1880–92 and run by the Methodist Episcopal Church, South[96]

- Seger Indian Training School, Colony, Indian Territory[57]

- Seneca, Shawnee, and Wyandotte Industrial Boarding School, Wyandotte, Indian Territory[43]

- Sequoyah High School, Tahlequah, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory[43]

- Shawnee Boarding School, near Shawnee, Indian Territory, open 1876[111]–1918[112]

- Shawnee Boarding School, Shawnee, Oklahoma, open 1923–61[41]

- Sheldon Jackson College, Presbyterian-run high school, then college, in Sitka, Alaska

- Sherman Indian High School, Riverside, California[58]

- Shiprock Boarding School, Shiprock, New Mexico[57]

- Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute, Albuquerque, New Mexico[57]

- Spencer Academy (sometimes referred to as the National School of the Choctaw Nation),[113] near Doaksville, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1842–1900[114]

- Springfield Indian School, Springfield, South Dakota[57]

- Stewart Indian School, Carson City, Nevada[57]

- Sulphur Springs Indian School, Pontotoc County, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory[115] open 1896–98[41]

- Theodore Roosevelt Indian Boarding School, founded in 1923 in buildings of the U.S. Army's closed Fort Apache, Arizona, as of 2016 still in operation as a tribal school[116]

- Thomas Indian School, near Irving, New York

- Tomah Indian School, Wisconsin[57]

- Tullahassee Mission School, Tullahassee, Creek Nation, Indian Territory, opened 1850 burned 1880[117]

- Tullahassee Manual Labor School, Tullahassee, Creek Nation, Indian Territory, open 1883–1914 for Creek Freedmen[117]

- Tushka Lusa Institute (later called Tuska Lusa or Tushkaloosa Academy),[93] near Talihina, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory opened 1892 for Choctaw Freedmen[118]

- Tuskahoma Female Academy, Lyceum, Choctaw Nation, Indian Territory, open 1892–1925[119]

- Wahpeton Indian School, Wahpeton, North Dakota, 1904–93. In 1993 its name was changed to Circle of Nations School and came under tribal control. Currently open.

- Wapanucka Academy (also sometimes called Allen Academy), near Bromide, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1851–1911 by the Presbyterian Church.[120]

- Wealaka Mission School Wealaka, Indian Territory, open 1882–1907[121]

- Wewoka Mission School, (also known as Ramsey Mission School)[122] near Wewoka, Seminole Nation, Indian Territory. Open 1868[123]–80[124] by the Presbyterian Mission Board.[96]

- Wheelock Academy, Millerton, Oklahoma,[43] closed 1955

- White's Manual Labor Institute, Wabash, Indiana. Open 1870[125]–95 and operated by the Quakers,[126]

- White's Manual Labor Institute, West Branch, Iowa,[127] open 1881–87[128]

- Wetumka Boarding School, Wetumka, Creek Nation, Indian Territory. Levering Manual Labor School transferred from the Baptists to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation in 1891 and they changed the name to the Wetumka Boarding School. Operated until 1910.[90]

- Wittenberg Indian School, Wittenberg, Wisconsin[57]

- Wrangell Institute, Presbyterian church-led intiative, run by the BIA in Wrangell, Alaska

- Yellow Springs School, Pontotoc County, Chickasaw Nation, Indian Territory,[129] open 1896–1905[41]

See also

- American Indian boarding schools in Wisconsin

- Canadian Indian residential school system

- Education for Extinction

- Fort Shaw Indian School Girls Basketball Team

- Native Americans in the United States

- Native schools in New Zealand

- Our Spirits Don't Speak English, a documentary about Native American boarding schools

- School segregation in the United States

- Stolen Generations, children of Australian Aboriginal descent who were removed from their families by the Australian and state government agencies

- Tobeluk v. Lind, a landmark case in Native education where 27 teenaged Alaskan Native plaintiffs brought suit against the State of Alaska claiming that their boarding school experiences were racial discrimination and educational inequity

References

- "What Were Boarding Schools Like for Indian Youth?". authorsden.com. Archived from the original on November 14, 2002. Retrieved February 8, 2006.

- Stephen Magagnini. "Long-suffering urban Indians find roots in ancient rituals". Sacramento Bee. California's Lost Tribes. Archived from the original on August 29, 2005. Retrieved February 8, 2006.

- Roberta Schiralli. The Vitality of Evenki and the Influence of Language Policy from the Early Soviet Union Until Today (PDF) (Master's Thesis). p. 23. Leiden University. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- "Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved February 8, 2006.

- "Boarding Schools STRUGGLING WITH CULTURAL REPRESSION". National Museum of the American Indian. National Museum of the American Indian. July 22, 2017. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

However, not all boarding school experiences were negative. Many of the Indian students had some good memories of their school days and made friends for life. They also acquired knowledge and learned useful skills that helped them later in life.

- Julie Davis, "American Indian Boarding School Experiences: Recent Studies from Native Perspectives", OAH Magazine of History 15#2 (2001), pp. 20–2 JSTOR 25163421

- Eric Miller (1994). "Washington and the Northwest War, Part One". Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- "The Great Confusion in Indian Affairs: Native Americans and Whites in the Progressive Era". Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved November 5, 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Saunt, Claudio (2005). Black, White, and Indian. Oxford University Press. p. 155.

- "To the Brothers of the Choctaw Nation". Yale Law School. 1803. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- Child, Brenda J. (1998). Boarding school seasons: American Indian families, 1900-1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1480-4.

- Foley, Henry. Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus. 1875. London: Burns and Oates. p. 352.

- Foley, p. 379

- Foley, p. 394

- Monaghan, E. J., Learning to Read and Write in Colonial America, University of Massachusetts Press. Boston: MA, 2005, pp. 55, 59

- Charla Bear, "American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many", Part 1, NPR, 12 May 2008, accessed 5 July 2011

- Schedler, George (1998). Racist Symbols and Reparations by George Schedler. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8476-8676-6. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1970), 170-172

- Taylor, Morris F. "The Carr–Penrose Expedition: General Sheridan's Winter Campaign, 1868–1869." Chronicles of Oklahoma 51#2 (June 1973): 159–76., p. 328.

- cite Jennifer Jones, Dee Ann Bosworth, Amy Lonetree, "American Indian Boarding Schools: An Exploration of Global Ethnic & Cultural Cleansing", Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways, 2011, accessed 25 January 2014

- Griffith, Jane A. (2015). News from School: Language, Time, and Place in the Newspapers of 1890s Indian Boarding Schools in Canada (PDF). Toronto, ON: York University YorkSpace. pp. 2–3, 18–19.

- Bosworth, Dee Ann. "American Indian Boarding Schools: An Exploration of Global, Ethnic & Cultural Cleansing" (PDF). www.sagchip.org. Mount Pleasant, Michigan: The Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture & Lifeways. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- Author unlisted (2001). Native American Issue: "The Challenges and Limitations of Assimilation", The Brown Quarterly 4(3), accessed 6 July 2011

- http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/cgi-bin/History/History-idx?type=turn&entity=History.AnnRep91p1.p0025&id=History.AnnRep91p1&isize=M

- Blakemore, Erin. "Alcatraz Had Some Surprising Prisoners: Hopi Men". HISTORY. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "About ICWA » NICWA".

- Smith, Andrea. "Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools", Amnesty Magazine, from Amnesty International website, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved February 8, 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Union of Ontario Indians press release: "Time will prove apology's sincerity", says Beaucage.

- Child, Brenda J. (1998). Boarding school seasons: American Indian families, 1900–1940. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-8032-1480-4.

- Brenda J., Child (1998). Boarding school seasons: American Indian families, 1900- 1940. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press c1998. p. 56. ISBN 0803214804.

- Brenda J., Child (1998). Boarding school seasons: American Indian families, 1900- 1940. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press c1998. p. 5. ISBN 0803214804.

- http://www.nativepartnership.org/site/PageServer?pagename=airc_hist_boardingschools

- Lomawaima & Child & Archuleta (2000). Away from Home: American Indian Boarding School Experiences. Heard Museum.

- Hutchinson, Elizabeth (2001). "Modern Native American art: Angel DeCora's transcultural aesthetics". The Art Bulletin New York. 83 (4): 740–56. doi:10.2307/3177230. JSTOR 3177230.

- Sa, Zitkala (2000). The school days of an Indian girl in The American 1890s: A cultural reader. Duke University Press. p. 352.

- Hultgren, Mary Lou (1989). To lead and to serve: American Indian education at Hampton institute 1878–1923. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy in cooperation with Hampton University.

- Hutchinson, Elizabeth (2001). "Modern Native American art: Angel DeCora's transcultural aesthetics". The Art Bulletin New York. 83 (4): 740–56. doi:10.2307/3177230. JSTOR 3177230.

- Brenda J. Child, Boarding schools In Frederick E. Hoxie, ed. Encyclopedia of North American Indians: Native American History, Culture, and Life From Paleo-Indians to the Present (1996) p. 80 online

- Williams, Samantha; M (Fall 2018). "Review". Transmotion. 4 (2): 187–188. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- Moyer, Kathryn. "Going back to the blanket: New outlooks on art instruction at the Carlisle Indian Industrial school. In Visualizing a mission: Artifacts and imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879–1918" (PDF).

- "BIA Schools". National Archives. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "United States. Office of Indian Affairs / Annual report of the commissioner of Indian affairs, for the year 1899 Part I". digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Carter, Kent, compiler. "Preliminary Inventory of the Office of the Five Civilized Tribes Agency Muscogee Area of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (Record Group 75). Appendix VI: List of Schools (Entry 600 and 601)" RootsWeb. 1994 (retrieved 25 Feb 2010)

- White, James D. "St. Patrick's Mission". Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Everett, Dianna. "Seger, John Homer (1846–1928)". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- McKellips, Karen K (October 1992). "Educational Practices in Two Nineteenth Century American Indian Mission Schools". Journal of American Indian Education. 32 (1).

- Federal Writers Project of the WPA (1941). Oklahoma: A Guide to the Sooner State. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 372–73. ISBN 9780403021857. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Asbury Manual Labor School and Mission". General Commission on Archives & History The United Methodist Church. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Lupo, Mark R. "Asbury School and Mission". Alabama Historical Markers. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Warde, Mary Jane (1999). George Washington Grayson and the Creek nation : 1843–1920. Norman, Okla.: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. pp. 43, 149. ISBN 0-8061-3160-8. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Doucette, Bob (April 29, 2002). "Chickasaws plan to move seminary". News OK. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Margery Pease, A Worthy Work in a Needy Time: The Montana Industrial School for Indians (Bond's Mission ) 1886–1897, Self-published in 1986. Reprinted in Billings, Mont.: M. Pease, [1993]

- "Burney Academy". cumberland.org. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- O'Dell, Larry. "Cameron". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Petter, Rodolphe (1953). "Cantonment Mennonite Mission (Canton, Oklahoma, USA)". Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- "Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. Cantonment School. (1903–27)". Archives.gov. US National Archives. Retrieved January 29, 2015.

- "Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs." National Archives. (retrieved 25 Feb 2010)

- "American Indian Boarding Schools." Archived February 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine 15 Sept 2003 (retrieved 25 Feb 2010)

- Lance, Dana (August 2014). "Chickasaw Children's Village Celebrates 10 Years of Service". Chickasaw Times. p. 12. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Agnew, Brad. "Cherokee Male and Female Seminaries". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Conley, Robert L. A Cherokee Encyclopedia. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2007:214. (Retrieved through Google Books, 23 July 2009.) ISBN 978-0-8263-3951-5.

- Chisholm, Johnnie Bishop (June 1926). "Harley Institute". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 4 (2). Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Burris, George W (June 1942). "Reminiscences Of Old Stonewall". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 20 (2). Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Davis, Caroline (December 1937). "Education of the Chickasaws 1856–1907". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 15 (4). Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Indian Boarding and Residential Schools Sites of Conscience Network". International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. (retrieved 25 Feb 2010)

- Gibson, Arrell Morgan (1981). Oklahoma, a History of Five Centuries. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 95, 111. ISBN 978-0806117584. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Cassity, Michael; Goble, Danney (2009). Divided hearts : the Presbyterian journey through Oklahoma history. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-8061-3848-0.

- Wright, Muriel H. (June 1930). "Additional Notes on Perryville, Choctaw Nation". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 8 (2). Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Fowler, Loretta (2010). Wives and husbands : gender and age in Southern Arapaho history. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-8061-4116-9.

- Gamino, Denise (August 17, 1983). "Judge Approves Closing Concho Indian School". News OK. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Acts and Resolutions of the Creek National Council". October 23, 1894. p. 9. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Peyer, Bernd (editor) (2007). American Indian Nonfiction: An Anthology of Writings, 1760s–1930s. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-8061-3708-7. Retrieved January 30, 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Thiesen, Barbara A (June 2006). "Every Beginning Is Hard: Darlington Mennonite Mission, 1880–1902". Mennonite Life. 61 (2).

- "Remembering Oak Hill Academy for Choctaw Freedmen". african-nativeamerican.blogspot. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Marsh, Raph (June 3, 1958). "Minco College History Deep". Chickasha Daily Express. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "Emahaka Mission". Seminole Nation. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "Euchee Mission Boarding School". Exploring Oklahoma History. blogoklahoma.us. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Department of the Interior. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Muskogee Area Office. Eufala High School". National Archives. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "Eufaula Dormitory". eots.org. Eastern Oklahoma Tribal Schools. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Site Markers – Folsom Training School". Broken Bow Chamber of Commerce. Broken Bow Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Smith, Tash (2014). Capture these Indians for the lord : Indians, Methodists, and Oklahomans, 1844–1939. University of Arizona Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-8165-3088-5. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form – Comanche Indian Mission Cemetery" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior National Park Service. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Biskupic, Joan M. (May 13, 1983). "Tribes' Hopes of Reopening Fort Sill Indian School Fading". News OK. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Miller, Floyd E. (September 1926). "Hillside Mission". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 4 (3): 225. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Rofini, Diane (editor); Peterson, Diana Franzusoff (editor). "Associated Executive Committee of Friends on Indian Affairs" (PDF). Haverford, Pennsylvania: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2013. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

transferring efforts from Hillside to another more pioneer station

CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - Ragland (1955), pp. 177–78

- "Jones Academy". Jones Academy. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Starr, Myra. "Creek (Mvskoke) Schools". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Foreman, Carolyn Thomas (1947). "Israel G. Vore and Levering Manual Labor School" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 25: 206. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form". United States Department of the Interior National Park Service: 3. May 16, 1974. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Mekasukey Academy". Seminole Nation. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- City of Morris: Morris Human Rights Commission

- Miles, Dennis B. "Choctaw Boarding Schools". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Flickinger, Robert Elliott (1914). The Choctaw Freedmen and The Story of Oak Hill Industrial Academy (PDF). Presbyterian Board of Missions for Freedmen. p. 103. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Flickinger (1914), pp. 210–15

- Koenig, Pamela. "Seminole Schools". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 10, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. Osage Agency. Osage Boarding School. (01/01/1874 – 12/31/1922)". National Archives. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Pirtle III, Caleb (2011). Trail of Broken Promises. Venture Galleries LLC. ISBN 978-0-9842-0837-1. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Kresge, Theda GoodFox (June 15, 2009). "The gravy had no lumps". Native American Times. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Johnson, Larry G. (2008). Tar Creek : a history of the Quapaw Indians, the world's largest lead and zinc discovery, and the Tar Creek Superfund site. Mustang, Okla.: Tate Pub. & Enterprises. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-60696-555-9. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Ellis, Clyde. "Rainy Mountain Boarding School". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- "Department of the Interior. Office of Indian Affairs. Red Moon School and Agency". archives.gov. U.S. National Archives. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Koenig, Pamela. "Riverside Indian School". Oklahoma State University. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Ragland, Hobert D (1955). "Missions of the Society of Friends, Sac and Fox Agency" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 33 (2): 172. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Ragland, Hobart D (1951). "Some Firsts In Lincoln County" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 29 (4): 420. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Wright, Catherine; Anders, Mary Ann (April 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form: Sacred Heart Mission Site". National Park Service. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Harley, Bruce (1994). Readings in Diocesan Heritage. 8, Seek and ye shall find: St. Boniface Indian Industrial School, 1888–1978. San Bernardino, CA: Diocese of San Bernardino. pp. i–137. OCLC 29934736.

- Nieberding, Velma (1954). "Catholic Education Among the Osage" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 32: 12–15. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Jackson, Joe C. (1954). "Schools Among the Minor Tribes in Indian Territory" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 32: 64–65. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Baker, Terri M. (editor); Henshaw, Connie Oliver (co-editor) (2007). Women who pioneered Oklahoma : stories from the WPA narratives. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3845-9. Retrieved February 1, 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Gilstrap, Harriet Patrick (1960). "Memoirs of a Pioneer Teacher" (PDF). Chronicles of Oklahoma. 38 (1): 21. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- WPA 1941, p. 308

- Spring, Joel (2012). Corporatism, social control, and cultural domination in education : from the radical right to globalization : the selected works of Joel Spring. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-415-53435-2. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Choctaw Schools and Missions". Rootsweb. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Constitution and Laws of the Chickasaw Nation together with the Treaties of 1832, 1833, 1834, 1837, 1852, 1855 and 1866. Library of Congress: Chickasaw Nation. October 15, 1896. p. 366. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- http://www.fortapachearizona.org/history/

- "Tullahassee Manual Labor School (1850–1924)". blackpast.org. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Tushka Lusa Academy – A School For Choctaw Freedmen". Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Stewart, Paul (November 26, 1931). "Choctaw Council House, Tuskahoma, Oklahoma". Antlers American. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- Wright, Muriel H. (December 1934). "Wapanucka Academy, Chickasaw Nation". Chronicles of Oklahoma. 12 (4). Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Settlers Claim Land". Bixby Historical Society. Retrieved January 30, 2015.

- "Chief Alice Brown Davis". Seminole Nation. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Fixico, Donald L. (2012). Bureau of Indian Affairs. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-313-39179-8. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Mulroy, Kevin (2007). The Seminole freedmen a history. Norman, Oklahoma.: Univ. of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3865-7. Retrieved January 31, 2015.

- Glenn, Elizabeth; Rafert, Stewart (2009). The Native Americans. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-87195-280-6. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- "Photos Of American Indians From White's Institute, Wabash, Indiana". Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Zagofsky, Al (November 17, 2012). "Josiah White's curious link to Jim Thorpe". Times News. Lehighton, Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- King, Thomas M. (2012). History of San Jose Quakers, west coast Friends : based on Joel Bean's diaries in Iowa and California. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-105-69540-7. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Sulphur Springs, p. 397

Further reading

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1995.

- Baird, W. David; Goble, Danney (1994). The Story of Oklahoma. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 217. ISBN 0-8061-2650-7. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- Child, Brenda J. (2000). Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, Lincoln: U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6405-2.

- Giago, Tim A. (2006). Children Left Behind: Dark Legacy of Indian Mission Boarding Schools. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light. ISBN 978-1574160864. OCLC 168659123.

- Meriam, Lewis et al., The Problem of Indian Administration, Brookings Institution, 1928 (full text online at Alaskool.org)

External links

- Bear, Charla, "American Indian Boarding Schools Haunt Many", NPR, May 12, 2008

- A Native American perspective on Indian Boarding Schools, "Our Spirits Don't Speak English: Indian Boarding School", Rich-Heape Films, 2008

- An Indian Boarding School Photo Gallery, University of Illinois

- Carolyn J. Marr, "Assimilation Through Education: Indian Boarding Schools in the Pacific Northwest Essay", University of Washington Digital Collection

- Playing for the World Documentary produced by Montana PBS

- Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools Documentary produced by KUED