Coacervate

Coacervates (/koʊəˈsɜːrvəts/ or /koʊˈæsərveɪts/) are organic-rich droplets formed via liquid-liquid phase separation, mainly resulting from association of oppositely charged molecules (macro-ions, polyelectrolytes, polysaccharides, proteins, etc.)[1] or from hydrophobic proteins (such as elastin-like polypeptides).[2] Coacervation is a phenomenon that produces coacervate colloidal droplets. When coacervation happens, two liquid phases will co-exist: a dense, polymer-rich phase (coacervate phase or coacervate droplets) and a very dilute, polymer-deficient phase (dilute phase). Coacervate droplets can measure from 1 to 100 micrometres across, while their soluble precursors[3][4] are typically on the order of less than 200 nm.[5] The name "coacervate" derives from the Latin coacervare, meaning "to assemble together or cluster".

The process of coacervation[6] was famously proposed by Alexander Oparin and J. B. S. Haldane (1929) as crucial in his early theory of abiogenesis (origin of life/proiskhozhdenie zhizni). This theory proposes that metabolism predated information replication, although the discussion as to whether metabolism or molecules capable of template replication came first in the origins of life remains open[7] and for decades the theory of Oparin and Haldane was the leading approach to the origin of life question.

History

These structures were first investigated by the Dutch chemist H.G. Bungenberg de Jong, in 1932. A wide variety of solutions can give rise to them; for example, coacervates form spontaneously when a disordered polypeptide, such as gelatin, reacts with another biologically derived polyelectrolyte, such as gum arabic. They are interesting not only in that they provide a locally segregated environment, but also in that their boundaries allow the selective absorption of simple organic molecules from the surrounding medium. For example, a mix of carbohydrate solution with a protein solution, will favor the spontaneous formation of amoeba-like coacervates which change shape, merge, divide, form "vacuoles", release "vacuole contents", and show other lifelike properties.[8] In Oparin's view this amounts to an elementary form of metabolism. British scientist Bernal commented that they are "the nearest we can come to cells without introducing any biological – or, at any rate, any living biological – substance." However, the lack of any mechanism by which coacervates can reproduce leaves them far short of being living systems.[9]

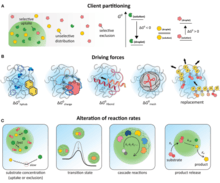

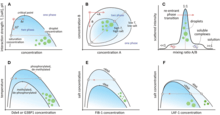

Complex coacervation

Complex coacervation commonly refers to the liquid-liquid phase separation that results when solutions of two oppositely charged macroions are mixed, resulting in the formation of a dense macroion-rich phase, the precursors of which are soluble complexes.[10][11][12] This has widely been found to be involved in the formation of biomolecular condensates, also known as membraneless organelles within cells.[13]

See also

- Jeewanu

- Microsphere

- Protocell

- Sol–gel process, condensation of monomers dispersed in a colloidal solution (sol) into a biphasic aqueous polymeric network (gel)

- Vesicle (biology and chemistry)

References

- Aumiller, William M.; Davis, Bradley W.; Keating, Christine D. (2014), "Phase Separation as a Possible Means of Nuclear Compartmentalization", International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology, Elsevier, 307: 109–149, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-800046-5.00005-9, ISBN 9780128000465, PMID 24380594

- Sharpe, Simon; Keeley, Fred W.; Muiznieks, Lisa D.; Reichheld, Sean E. (2017-05-30). "Direct observation of structure and dynamics during phase separation of an elastomeric protein". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (22): E4408–E4415. doi:10.1073/pnas.1701877114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5465911. PMID 28507126.

- Water, J.J.; Schack, M.M.; Velazquez-Campoy, A.; Maltesen, M.J.; van de Weert, M.; Jorgensen, L. (2014). "Complex coacervates of hyaluronic acid and lysozyme: Effect on protein structure and physical stability". European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. 88 (2): 325–331. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2014.09.001. PMID 25218319.

- Definition of coacervate, Memidex dictionary.

- Schmitt, Christophe; Turgeon, Sylvie L. (2011). "Protein/polysaccharide complexes and coacervates in food systems". Advances in Colloid and Interface Science. 167 (1–2): 63–70. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2010.10.001. PMID 21056401.

- Bungenberg de Jong, H. G., and H. R. Kruyt (1929). "Coacervation (partial miscibility in colloid systems)". Proc Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie Wetenschappen 32: 849—856

- Origins of Life and Evolution of the Biosphere, Volume 40, Numbers 4-5, October 2010 , pp. 347–497(151)

- Creating Coacervates. Larry Flammer, Indiana State University.

- Dick, Steven J. (1999). The Biological Universe: The Twentieth Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate and the Limits of Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-521-66361-8.

- Kizilay, E (Sep 14, 2011). "Complexation and coacervation of polyelectrolytes with oppositely charged colloids". Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 167 (1–2): 24–37. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2011.06.006. PMID 21803318.

- Research — Complex Coacervates Archived 2018-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Tirrell Research Group.

- Srivastava, Samanvaya; Tirrell, Matthew V. (2016). "Polyelectrolyte Complexation". Advances in Chemical Physics. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 499–544. doi:10.1002/9781119290971.ch7. ISBN 9781119290971.

- C. P. Brangwynne et al., Germline P Granules Are Liquid Droplets That Localize by Controlled Dissolution/Condensation. Science 324, 1729 (2009).