Camden, New Jersey

Camden is a city in and the county seat of Camden County, New Jersey, in the United States. Camden is located directly across the Delaware River from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the 2010 U.S. Census, the city had a population of 77,344.[10][12][13] Camden is the 12th most populous municipality in New Jersey. The city was incorporated on February 13, 1828.[22] Camden has been the county seat of Camden County[23] since the county was formed on March 13, 1844.[22] The city derives its name from Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden.[24][25] Camden is made up of over twenty different neighborhoods.[26][27][28][29]

Camden, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

| City of Camden | |

From top to bottom, left to right: Camden skyline, Camden waterfront, Riversharks game at Campbell's Field, Walt Whitman House, Camden Federal Courthouse | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Motto(s): In a Dream, I Saw a City Invincible[1] | |

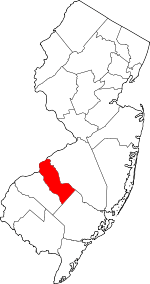

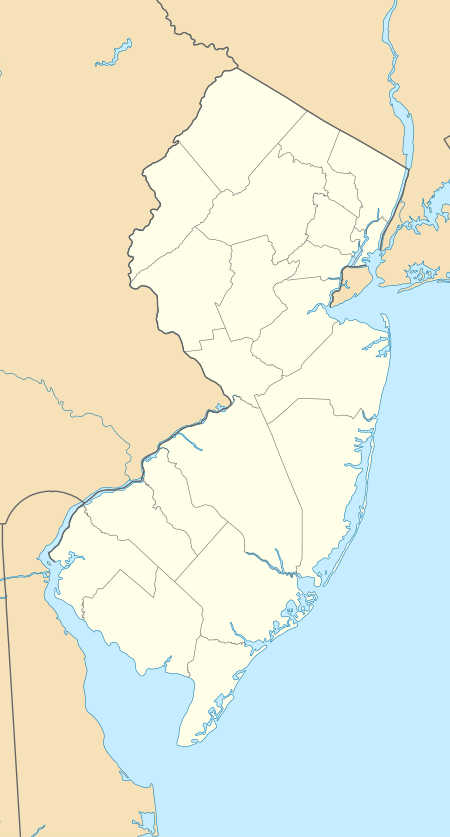

Location within Camden County | |

Camden Location in Camden County  Camden Location in New Jersey  Camden Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 39.94°N 75.105°W[2][3] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Camden |

| Settled | 1626 |

| Incorporated | February 13, 1828 |

| Named for | Charles Pratt, 1st Earl Camden |

| Government | |

| • Type | Faulkner Act (Mayor-Council) |

| • Body | City Council |

| • Mayor | Francisco "Frank" Moran (D, term ends December 31, 2021)[5][6] |

| • Administrator | Jason J. Asuncion[7] |

| • Municipal clerk | Luis Pastoriza[8] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 10.341 sq mi (26.784 km2) |

| • Land | 8.921 sq mi (23.106 km2) |

| • Water | 1.420 sq mi (3.677 km2) 13.73% |

| Area rank | 208th of 566 in state 7th of 37 in county[2] |

| Elevation | 16 ft (5 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 77,344 |

| • Estimate (2019)[14] | 73,562 |

| • Rank | 12th of 566 in state 1st of 37 in county[15] |

| • Density | 8,669.6/sq mi (3,347.4/km2) |

| • Density rank | 42nd of 566 in state 2nd of 37 in county[15] |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Codes | |

| Area code(s) | 856[18] |

| FIPS code | 3400710000[2][19][20] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0885177[2][21] |

| Website | www |

Beginning in the early 1900s, Camden was a prosperous industrial city, and remained so throughout the Great Depression and World War II. During the 1950s, Camden manufacturers began gradually closing their factories and moving out of the city. With the loss of manufacturing jobs came a sharp population decline. The growth of the interstate highway system also played a large role in suburbanization, which resulted in white flight. Civil unrest and crime became common in Camden. In 1971, civil unrest reached its peak, with riots breaking out in response to the death of Horacio Jimenez, a Puerto Rican motorist who was killed by two police officers.[30]

The Camden waterfront holds three tourist attractions, the USS New Jersey; the BB&T Pavilion; and the Adventure Aquarium.[31] The city is the home of Rutgers University–Camden, which was founded as the South Jersey Law School in 1926,[32] and Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, which opened in 2012. Camden also houses both Cooper University Hospital and Virtua Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center. The "eds and meds" institutions account for roughly 45% of Camden's total employment.[33]

There were 23 murders in Camden in 2017, the lowest in the city in three decades, part of a significant decline in violent crime since 2012.[34]

History

Early history

In 1626, Fort Nassau was established by the Dutch West India Company at the confluence of Big Timber Creek and the Delaware River. Throughout the 17th century, Europeans settled along the Delaware, competing to control the local fur trade. After the Restoration in 1660, the land around Camden was controlled by nobles serving under King Charles II, until it was sold off to a group of New Jersey Quakers in 1673.[35] The area developed further when a ferry system was established along the east side of the Delaware River to facilitate trade between Fort Nassau and Philadelphia, the growing capital of the Quaker colony of Pennsylvania directly across the river. By the 1700s, Quakers and the Lenni Lenape, the indigenous inhabitants, were coexisting. The Quakers' expansion and use of natural resources, in addition to the introduction of alcohol and infectious disease, diminished the Lenape's population in the area.[35]

The 1688 order of the County Court of Gloucester that sanctioned ferries between New Jersey and Philadelphia was: "Therefore we permit and appoint that a common passage or ferry for man or beast be provided, fixed and settled in some convenient and proper place between ye mouths or entrance of Cooper's Creek and Newton Creek, and that the government, managing and keeping of ye same be committed to ye said William Roydon and his assigns, who are hereby empowered and appointed to establish, fix and settle ye same within ye limits aforesaid, wherein all other persons are desired and requested to keep no other common or public passage or ferry."[36] The ferry system was located along Cooper Street and was turned over to Daniel Cooper in 1695.[37] Its creation resulted in a series of small settlements along the river, largely established by three families: the Coopers, the Kaighns, and the Mickels, and these lands would eventually be combined to create the future city.[37] Of these, the Cooper family had the greatest impact on the formation of Camden. In 1773, Jacob Cooper developed some of the land he had inherited through his family into a "townsite," naming it Camden after Charles Pratt, the Earl of Camden.[24][25]

19th century

For over 150 years, Camden served as a secondary economic and transportation hub for the Philadelphia area. However, that status began to change in the early 19th century. Camden was incorporated as a city on February 13, 1828, from portions of Newton Township, while the area was still part of Gloucester County. One of the U.S.'s first railroads, the Camden and Amboy Railroad, was chartered in Camden in 1830. The Camden and Amboy Railroad allowed travelers to travel between New York City and Philadelphia via ferry terminals in South Amboy, New Jersey and Camden. The railroad terminated on the Camden Waterfront, and passengers were ferried across the Delaware River to their final Philadelphia destination. The Camden and Amboy Railroad opened in 1834 and helped to spur an increase in population and commerce in Camden.[38]

Horse ferries, or team boats, served Camden in the early 1800s. The ferries connected Camden and other Southern New Jersey towns to Philadelphia. Ferry systems allowed Camden to generate business and economic growth.[37] "These businesses included lumber dealers, manufacturers of wooden shingles, pork sausage manufacturers, candle factories, coachmaker shops that manufactured carriages and wagons, tanneries, blacksmiths and harness makers."[37] The Cooper's Ferry Daybook, 1819–1824, documenting Camden's Point Pleasant Teamboat, survives to this day.[39] Originally a suburban town with ferry service to Philadelphia, Camden evolved into its own city. Until 1844, Camden was a part of Gloucester County.[22] In 1840 the city's population had reached 3,371 and Camden appealed to state legislature, which resulted in the creation of Camden County in 1844.[37]

The poet Walt Whitman spent his later years in Camden. He bought a house on Mickle Street in March 1884. Whitman spent the remainder of his life in Camden and died in 1892 of a stroke. Whitman was a prominent member of the Camden community at the end of the nineteenth century.[40]

Camden quickly became an industrialized city in the later half of the nineteenth century. In 1860 Census takers recorded eighty factories in the city and the number of factories grew to 125 by 1870.[37] Camden began to industrialize in 1891 when Joseph Campbell incorporated his business Campbell's Soup. Through the Civil War era Camden gained a large immigrant population which formed the base of its industrial workforce.[30] Between 1870 and 1920 Camden's population grew by 96,000 people due to the large influx of immigrants.[37] Like other industrial cities, Camden prospered during strong periods of manufacturing demand and faced distress during periods of economic dislocation.[41]

First half of the 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century Camden became an industrialized city. At the height of Camden's industrialization, 12,000 workers were employed at RCA Victor,[42] while another 30,000 worked at New York Shipbuilding.[43] Camden Forge Company supplied materials for New York Ship during both world wars.[44] RCA had 23 out of 25 of its factories inside Camden. Campbell Soup was also a major employer.[45] In addition to major corporations, Camden also housed many small manufacturing companies as well as commercial offices.[30]

From 1899 to 1967, Camden was the home of New York Shipbuilding Corporation, which at its World War II peak was the largest and most productive shipyard in the world.[46] Notable naval vessels built at New York Ship include the ill-fated cruiser USS Indianapolis and the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk. In 1962, the first commercial nuclear-powered ship, the NS Savannah, was launched in Camden.[47] The Fairview Village section of Camden (initially Yorkship Village) is a planned European-style garden village that was built by the Federal government during World War I to house New York Shipbuilding Corporation workers.[48]

From 1901 through 1929, Camden was headquarters of the Victor Talking Machine Company, and thereafter to its successor RCA Victor, the world's largest manufacturer of phonographs and phonograph records for the first two-thirds of the 20th century.[49] Victor established some of the first commercial recording studios in Camden where Enrico Caruso, Arturo Toscanini, Serge Rachmaninoff, Leopold Stokowski, John Philip Sousa, Woody Guthrie, Fats Waller & The Carter Family among many others, made famous recordings. General Electric reacquired RCA and the remaining Camden factories in 1986.[50]

In 1919 plans for the Delaware River Bridge were enacted as a means to reduce ferry traffic between Camden and Philadelphia. The bridge was estimated to cost $29 million, but the total cost at the end of the project was $37,103,765.42. New Jersey and Pennsylvania would each pay half of the final cost for the bridge. The bridge was opened at midnight on July 1, 1926. Thirty years later, in 1956 the bridge was renamed to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge.[51]

During the 1930s Camden faced a decline in economic prosperity due to the Great Depression. By the mid-1930s the city had to pay its workers in scrip because they could not pay them in currency. Camden's industrial foundation kept the city from going bankrupt. Major corporations such as Campbell's Soup, New York Shipbuilding Corporation and RCA Victor employed close to 25,000 people through the depression years.[30] New companies were also being created during this time. On June 6, 1933, the city hosted the first drive-in movie theater.[52][53]

Between 1929 and 1957, Camden Central Airport was active; during the 1930s, it was Philadelphia's main airport. It was located in Pennsauken Township, on the north bank of the Cooper River. Its terminal building was beside what became known as Airport Circle.[54]

Camden's ethnic demographic shifted dramatically at the beginning of the twentieth century. German, British, and Irish immigrants made up the majority of the city at the beginning of the second half of the nineteenth century. By 1920 Italian and Eastern European immigrants had become the majority of the population.[37] African Americans had also been present in Camden since the 1830s. The migration of African Americans from the south increased during World War II. The different ethnic groups began to form segregated communities within the city and around religious organizations. Communities formed around figures such as Tony Mecca from the Italian neighborhood, Mario Rodriguez from the Puerto Rican neighborhood, and Ulysses Wiggins from the African American neighborhood.[30]

Second half of the 20th century

After close to 50 years of economic and industrial growth, the city of Camden experienced a period of economic stagnation and deindustrialization: after reaching a peak of 43,267 manufacturing jobs in 1950, there was an almost continuous decline to a new low of 10,200 manufacturing jobs in the city by 1982. With this industrial decline came a plummet in population: in 1950 there were 124,555 residents, compared to just 84,910 in 1980.[30] Alongside these declines, civil unrest and criminal activity rose in the city. From 1981 to 1990, mayor Randy Primas fought to renew the city economically. Ultimately Primas had not secured Camden's economic future as his successor, mayor Milton Milan, declared bankruptcy for the city in July 1999.

Industrial decline

After WWII, Camden's biggest manufacturing companies, RCA Victor and the Campbell Soup Company, decentralized their production operations. This period of capital flight was a means to regain control from Unionized workers and to avoid the rising labor costs unions demanded from the company. Campbell's kept its corporate headquarters in Camden, but the bulk of its cannery production was located elsewhere after a union worker's strike in 1934.[55] Local South Jersey tomatoes were replaced in 1979 by Californian industrially produced tomato paste.

During the 1940s, RCA Victor began relocating some production to rural Indiana to employ low-wage ethnic Scottish-Irish workers and since 1968, has employed Mexican workers from Chihuahua.[56]

The NY Shipbuilding Corporation, founded in 1899, shut down in 1967 due to mismanagement, unrest amongst labor workers, construction accidents, and a low demand for shipbuilding. When NY ship shut down, Camden lost its largest postwar employer.[57]

The opening of the Cherry Hill Mall in 1961 increased Cherry Hill's property value while decreasing Camden's. Enclosed suburban malls, especially ones like Cherry Hill's, which boasted well-lit parking lots and babysitting services, were preferred by white middle-class over Philadelphia's central business district.[58] Cherry Hill became the designated regional retail destination. The mall, as well as the Garden State Racetrack, the Cherry Hill Inn, and the Hawaiian Cottage Cafe, attracted the white middle class of Camden to the suburbs initially.

Manufacturing companies were not the only businesses that were hit. After they left Camden and outsourced their production, White-collar companies and workers followed suit, leaving for the newly constructed offices of Cherry Hill.[59]

Unionization

Approximately ten million cans of soup were produced at Campbell's per day. This put additional stress on cannery workers who already faced dangerous conditions in an outmoded, hot and noisy factory. The Dorrance family, founders of Campbell's, made an immense amount of profit while lowering the costs of production.[60]

The initial union strikes' intention was to gain union recognition, which they earned in 1940. Several other strikes would follow the next several decades, all demanding reasonable pay. Campbell's started hiring seasonal workers, immigrants, and Contingent labor, the latter of which they would fire 8 weeks after hiring.

Civil unrest and crime

On September 6, 1949, mass murderer Howard Unruh went on a killing spree in his Camden neighborhood killing 13 people. Unruh, who was convicted and subsequently confined to a state psychiatric facility, died on October 19, 2009.[61]

A civilian and a police officer were killed in a September 1969 riot, which broke out in response to accusation of police brutality.[62][63] Two years later, public disorder returned with widespread riots in August 1971, following the death of a Puerto Rican motorist at the hands of white police officers. When the officers were not charged, Hispanic residents took to the streets and called for the suspension of those involved. The officers were ultimately charged, but remained on the job and tensions soon flared. On the night of August 19, 1971, riots erupted, and sections of downtown were looted and torched over the next three days.[30][64] Fifteen major fires were set before order was restored, and ninety people were injured. City officials ended up suspending the officers responsible for the death of the motorist, but they were later acquitted by a jury.[65][66]

The Camden 28 were a group of anti-Vietnam War activists who, in 1971, planned and executed a raid on the Camden draft board, resulting in a high-profile trial against the activists that was seen by many as a referendum on the Vietnam War in which 17 of the defendants were acquitted by a jury even though they admitted having participated in the break-in.[67]

In 1996, Governor of New Jersey Christine Todd Whitman frisked Sherron Rolax, a 16-year-old African-American youth, an event which was captured in an infamous photograph. Rolax alleged his civil rights were violated and sued the state of New Jersey.[68] His suit was later dismissed.[69]

Revitalization efforts

In 1981, Randy Primas was elected mayor of Camden, but entered office "haunted by the overpowering legacy of financial disinvestment." Following his election, the state of New Jersey closed the $4.6 million deficit that Primas had inherited, but also decided that Primas should lose budgetary control until he began providing the state with monthly financial statements, among other requirements.[30] When he regained control, Primas had limited options regarding how to close the deficit, and so in an attempt to renew Camden, Primas campaigned for the city to adopt a prison and a trash-to-steam incinerator. While these two industries would provide some financial security for the city, the proposals did not go over well with residents, who overwhelmingly opposed both the prison and the incinerator.

While the proposed prison, which was to be located on the North Camden waterfront, would generate $3.4 million for Camden, Primas faced extreme disapproval from residents. Many believed that a prison in the neighborhood would negatively affect North Camden's "already precarious economic situation." Primas, however, was wholly concerned with the economic benefits: he told The New York Times, "The prison was a purely economic decision on my part."[30] Eventually, on August 12, 1985, the Riverfront State Prison opened its doors.

Camden residents also objected to the trash-to-steam incinerator, which was another proposed industry. Once again, Primas "...was motivated by fiscal more than social concerns," and he faced heavy opposition from Concerned Citizens of North Camden (CCNC) and from Michael Doyle, who was so opposed to the plant that he appeared on CBS's 60 Minutes, saying "Camden has the biggest concentration of people in all the county, and yet there is where they're going to send in this sewage... ...everytime you flush, you send to Camden, to Camden, to Camden."[30] Despite this opposition, which eventually culminated in protests, "the county proceeded to present the city of Camden with a check for $1 million in March 1989, in exchange for the 18 acres (7.3 ha) of city-owned land where the new facility was to be built... ...The $112 million plant finally fired up for the first time in March 1991."[30]

Other notable events

Despite the declines in industry and population, other changes to the city took place during this period:

- In 1950, Rutgers University absorbed the former College of South Jersey to create Rutgers University–Camden.[32]

- In 1992, the state of New Jersey under the Florio administration made an agreement with GE to ensure that GE would not close the remaining buildings in Camden. The state of New Jersey would build a new high-tech facility on the site of the old Campbell Soup Company factory and trade these new buildings to GE for the existing old RCA Victor buildings. Later, the new high tech buildings would be sold to Martin Marietta. In 1994, Martin Marietta merged with Lockheed to become Lockheed Martin. In 1997, Lockheed Martin divested the old Victor Camden Plant as part of the birth of L-3 Communications.[70]

- In 1999, Camden was selected as the location for the USS New Jersey (BB-62).[71] That ship remains in Camden.

21st century

Originally the city's main industry was manufacturing, and in recent years Camden has shifted its focus to eds and meds (education and medicine) in an attempt to revitalize itself. Of the top employers in Camden, many are education and/or healthcare providers: Cooper University Hospital, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Rowan University, Rutgers University-Camden, Camden County College, Virtua, Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center, and CAMcare are all top employers.[72] The eds and meds industry itself is the single largest source of jobs in the city: of the roughly 25,000 jobs in the city, 7,500 (30%) of them come from eds and meds institutions. The second largest source of jobs in Camden is the retail trade industry, which provides roughly 3,000 (12%) jobs.[73] While already the largest employer in the city, the eds and meds industry in Camden is growing and is doing so despite falling population and total employment: From 2000 to 2014, population and total employment in Camden fell by 3% and 10% respectively, but eds and meds employment grew by 67%.[72]

Despite previous failures to transform the Camden Waterfront, in September 2015 Liberty Property Trust and Mayor Dana Redd announced an $830 million plan to rehabilitate the waterfront. The project, which is the biggest private investment in the city's history, aims to redevelop 26 acres (11 ha) of land south of the Ben Franklin Bridge and includes plans for 1.5 million square feet of commercial space, 211 residences, a 130-room hotel, more than 4,000 parking spaces, a downtown shuttle bus, a new ferry stop, a riverfront park, and two new roads. The project is a modification of a previous $1 billion proposal by Liberty Property Trust, which would have redeveloped 37.2 acres (15.1 ha) and would have included 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) of commercial space, 1,600 homes, and a 140-room hotel.[74] On March 11, 2016, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority approved the modified plans and officials like Timothy J. Lizura of the NJEDA expressed their enthusiasm: "It's definitely a new day in Camden. For 20 years, we've tried to redevelop that city, and we finally have the traction between a very competent mayor's office, the county police force, all the educational reforms going on, and now the corporate interest. It really is the right ingredient for changing a paradigm which has been a wreck."[75]

In 2013, the New Jersey Economic Development Authority created the New Jersey Economic Opportunity Act, which provides incentives for companies to relocate to or remain in economically struggling locations in the state. These incentives largely come in the form of tax breaks, which are payable over 10 years and are equivalent to a project's cost. According to The New York Times, "...the program has stimulated investment of about $1 billion and created or retained 7,600 jobs in Camden."[30][39] This NJEDA incentive package has been used by organizations and firms such as the Philadelphia 76ers, Subaru of America, Lockheed Martin, and Holtec International.[76][77][78][79]

In late 2014 the Philadelphia 76ers broke ground in Camden (across the street from the BB&T Pavilion) to construct a new 125,000-square-foot training complex. The Sixers Training Complex includes an office building and a 66,230-square-foot basketball facility with two regulation-size basketball courts, a 2,800-square-foot locker room, and a 7,000-square-foot roof deck. The $83 million complex had its grand opening on September 23, 2016, and was expected to provide 250 jobs for the city of Camden.[79][80][81]

Also in late 2014, Subaru of America announced that in an effort to consolidate their operations, their new 250,000-square-foot (23,000 m2) headquarters would be located in Camden. The $118 million project broke ground in December 2015 but was put on hold in mid-2016 because the original plans for the complex had sewage and waste water being pumped into an outdated sewage system. Adjustments to the plans have been made and the project is expected to be completed in 2017, creating up to 500 jobs in the city upon completion.[78][82]

Several smaller-scale projects and transitions also took place during the 21st century.

In preparation for the 2000 Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, various strip clubs, hotels, and other businesses along Admiral Wilson Boulevard were torn down in 1999, and a park that once existed along the road was replenished.[83]

In 2004, conversion of the old RCA Victor Building 17 to The Victor, an upscale apartment building was completed.[84] The same year, the River LINE, between the Entertainment Center at the Waterfront in Camden and the Transit Center in Trenton, was opened, with a stop directly across from The Victor.

In 2010, massive police corruption was exposed that resulted in the convictions of several policemen, dismissals of 185 criminal cases, and lawsuit settlements totaling $3.5 million that were paid to 88 victims.[85][86][87] On May 1, 2013, the Camden Police Department was dissolved and the newly formed Camden County Police Department took over full responsibility for policing the city. This move was met with some disapproval from residents of both the city and county.[88]

As of 2019, numerous projects were underway downtown and along the waterfront.[89]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city had a total area of 10.341 square miles (26.784 km2), including 8.921 square miles (23.106 km2) of land and 1.420 square miles (3.677 km2) of water (13.73%).[2][3]

Camden borders Collingswood, Gloucester City, Oaklyn, Pennsauken Township and Woodlynne in Camden County, as well as Philadelphia across the Delaware River in Pennsylvania.[90][91][92] Just offshore of Camden is Pettys Island, which is part of Pennsauken Township. The Cooper River (popular for boating) flows through Camden, and Newton Creek forms Camden's southern boundary with Gloucester City.

Camden contains the United States' first federally funded planned community for working class residents, Yorkship Village (now called Fairview).[93] The village was designed by Electus Darwin Litchfield, who was influenced by the "garden city" developments popular in England at the time.[94]

Neighborhoods

Camden contains more than 20 generally recognized neighborhoods:[29]

- Ablett Village

- Bergen Square

- Beideman

- Broadway

- Centerville

- Center City/Downtown Camden/Central Business District

- Central Waterfront

- Cooper

- Cooper Grant

- Cooper Point

- Cramer Hill

- Dudley

- East Camden

- Fairview

- Gateway

- Kaighn Point

- Lanning Square

- Liberty Park

- Marlton

- Morgan Village

- North Camden

- Parkside

- Pavonia

- Pyne Point

- Rosedale

- South Camden

- Stockton

- Waterfront South

- Whitman Park

- Yorkship

Port

On the Delaware River, with access to the Atlantic Ocean, the Port of Camden handles break bulk, bulk cargo, as well as some containers. Terminals fall under the auspices of the South Jersey Port Corporation as well as private operators such as Holt Logistics/Holtec International. The port receives hundreds of ships moving international and domestic cargo annually and is one the nation's largest shipping centers for wood products, cocoa and perishables.[95]

Climate

Camden has a humid subtropical climate (Cfa in the Köppen climate classification).

| Climate data for Camden, New Jersey | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41 (5) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

65 (18) |

74 (23) |

82 (28) |

87 (31) |

85 (29) |

78 (26) |

67 (19) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

65.083 (18.38) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 24 (−4) |

26 (−3) |

33 (1) |

42 (6) |

52 (11) |

61 (16) |

67 (19) |

65 (18) |

58 (14) |

46 (8) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

45.083 (7.27) |

Source: <Weather.com >Camden, NJ (08102). Weather.com. 2016 https://weather.com/weather/monthly/l/Camden+NJ+08102:4:US. Retrieved September 14, 2016. Missing or empty |title= (help) | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1840 | 3,371 | — | |

| 1850 | 9,479 | 181.2% | |

| 1860 | 14,358 | 51.5% | |

| 1870 | 20,045 | 39.6% | |

| 1880 | 41,659 | 107.8% | |

| 1890 | 58,313 | 40.0% | |

| 1900 | 75,935 | 30.2% | |

| 1910 | 94,538 | 24.5% | |

| 1920 | 116,309 | 23.0% | |

| 1930 | 118,700 | 2.1% | |

| 1940 | 117,536 | −1.0% | |

| 1950 | 124,555 | 6.0% | |

| 1960 | 117,159 | −5.9% | |

| 1970 | 102,551 | −12.5% | |

| 1980 | 84,910 | −17.2% | |

| 1990 | 87,492 | 3.0% | |

| 2000 | 79,318 | −9.3% | |

| 2010 | 77,344 | −2.5% | |

| Est. 2019 | 73,562 | [14][96][97] | −4.9% |

| Population sources: 1840–2000[98][99] 1840–1920[100] 1840[101] 1850–1870[102] 1850[103] 1870[104] 1880–1890[105] 1890–1910[106] 1840–1930[107] 1930–1990[108] 2000[109][110][111] 2010[10][11][12][13] | |||

| Demographic profile | 1950[112] | 1970[112] | 1990[112] | 2010[10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 85.9% | 59.8% | 19.0% | 17.6% |

| —Non-Hispanic | N/A | 52.9% | 14.4% | 4.9% |

| Black or African American | 14.0% | 39.1% | 56.4% | 48.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | N/A | 7.6% | 31.2% | 47.0% |

| Asian | — | 0.2% | 1.3% | 2.1% |

As of 2006, 52% of the city's residents lived in poverty, one of the highest rates in the nation.[113] The city had a median household income of $18,007, the lowest of all U.S. communities with populations of more than 65,000 residents, making it America's poorest city.[114] A group of poor Camden residents were the subject of a 20/20 special on poverty in America broadcast on January 26, 2007, in which Diane Sawyer profiled the lives of three young children growing up in Camden.[115] A follow-up was shown on November 9, 2007.[116]

In 2011, Camden's unemployment rate was 19.6%, compared with 10.6% in Camden County as a whole.[117] As of 2009, the unemployment rate in Camden was 19.2%, compared to the 10% overall unemployment rate for Burlington, Camden and Gloucester counties and a rate of 8.4% in Philadelphia and the four surrounding counties in Southeastern Pennsylvania.[118]

2010 Census

The 2010 United States Census counted 77,344 people, 24,475 households, and 16,912.225 families in the city. The population density was 8,669.6 per square mile (3,347.4/km2). There were 28,358 housing units at an average density of 3,178.7 per square mile (1,227.3/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 17.59% (13,602) White, 48.07% (37,180) Black or African American, 0.76% (588) Native American, 2.12% (1,637) Asian, 0.06% (48) Pacific Islander, 27.57% (21,323) from other races, and 3.83% (2,966) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 47.04% (36,379) of the population.[10] The Hispanic population of 36,379 was the tenth-highest of any municipality in New Jersey and the proportion of 47.0% was the state's 16th-highest percentage.[119][120] The Puerto Rican population was 30.7%.[10]

The 24,475 households accounted 37.9% with children under the age of 18 living with them; 22.3% were married couples living together; 37.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 30.9% were non-families. Of all households, 24.8% were made up of individuals, and 7.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.02 and the average family size was 3.56.[10]

In the city, the population age was spread out with 31.0% under the age of 18, 13.1% from 18 to 24, 28.0% from 25 to 44, 20.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 28.5 years. For every 100 females, the population had 94.7 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 91.0 males.[10]

The city of Camden was 47% Hispanic of any race, 44% non-Hispanic black, 6% non-Hispanic white, and 3% other. Camden is predominately populated by African Americans and Puerto Ricans.[10]

The Census Bureau's 2006–2010 American Community Survey showed that (in 2010 inflation-adjusted dollars) median household income was $27,027 (with a margin of error of +/- $912) and the median family income was $29,118 (+/- $1,296). Males had a median income of $27,987 (+/- $1,840) versus $26,624 (+/- $1,155) for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,807 (+/- $429). About 33.5% of families and 36.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 50.3% of those under age 18 and 26.2% of those age 65 or over.[121]

2000 Census

As of the 2000 United States Census[19] there were 79,904 people, 24,177 households, and 17,431 families residing in the city. The population density was 9,057.0 people per square mile (3,497.9/km2). There were 29,769 housing units at an average density of 3,374.3 units per square mile (1,303.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 16.84% White, 53.35% African American, 0.54% Native American, 2.45% Asian, 0.07% Pacific Islander, 22.83% from other races, and 3.92% from two or more races. 38.82% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[109][110][111]

There were 24,177 households out of which 42.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 26.1% were married couples living together, 37.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.9% were non-families. 22.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.52 and the average family size was 4.00.[109][110][111]

In the city, the population is quite young with 34.6% under the age of 18, 12.0% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 16.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.0 males.[109][110][111]

The median income for a household in the city was $23,421, and the median income for a family was $24,612. Males had a median income of $25,624 versus $21,411 for females. The per capita income for the city is $9,815. 35.5% of the population and 32.8% of families were below the poverty line. 45.5% of those under the age of 18 and 23.8% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.[109][110][111]

In the 2000 Census, 30.85% of Camden residents identified themselves as being of Puerto Rican heritage. This was the third-highest proportion of Puerto Ricans in a municipality on the United States mainland, behind only Holyoke, Massachusetts and Hartford, Connecticut, for all communities in which 1,000 or more people listed an ancestry group.[122]

Religion

Camden has religious institutions including many churches and their associated non-profit organizations and community centers such as the Little Rock Baptist Church in the Parkside section of Camden, First Nazarene Baptist Church, Kaighn Avenue Baptist Church, and the Parkside United Methodist Church. Other congregations that are active now are Newton Monthly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, on Haddon Avenue and Cooper Street and the Masjid at 1231 Mechanic St, Camden, NJ 08104 .

The first Scientology church was incorporated in December 1953 in Camden by L. Ron Hubbard, his wife Mary Sue Hubbard, and John Galusha.[123][124]

Father Michael Doyle, the pastor of Sacred Heart Catholic Church located in South Camden, has played a large role in Camden's spiritual and social history. In 1971, Doyle was part of the Camden 28, a group of anti-Vietnam War activists who planned to raid a draft board office in the city. This is noted by many as the start of Doyle's activities as a radical 'Catholic Left'. Following these activities, Monsignor Doyle went on to become the pastor of Sacred Heart Church, remaining known for his poetry and activism.[125] Monsignor Doyle and the Sacred Heart Church's main mission is to form a connection between the primarily white suburban surrounding areas and the inner-city of Camden.[126]

In 1982, Father Mark Aita of Holy Name of Camden founded the St. Luke's Catholic Medical Services. Aita, a medical doctor and a member of the Society of Jesus, created the first medical system in Camden that did not use rotating primary care physicians. Since its conception, St. Luke's has grown to include Patient Education Classes as well as home medical services, aiding over seven thousand Camden residents.[127][128]

Culture

Camden's role as an industrial city gave rise to distinct neighborhoods and cultural groups that have affected the growth and decline of the city over the course of the 20th century. Camden is also home to historic landmarks detailing its rich history in literature, music, social work, and industry such as the Walt Whitman House,[129] the Walt Whitman Cultural Arts Center, the Rutgers–Camden Center for the Arts and the Camden Children's Garden.

Camden's cultural history has been greatly affected by both its economic and social position over the years. From 1950 to 1970, industry plummeted, resulting in close to 20,000 jobs being lost for Camden residents.[130] This mass unemployment as well as social pressure from neighboring townships caused an exodus of citizens, mostly white. This gap was filled by new African American and Latino citizens and led to a restructuring of Camden's communities. The number of White citizens who left to neighboring towns such as Collingswood or Cherry Hill left both new and old African American and Latino citizens to re-shape their community. To help in this process, numerous not-for-profit organizations such as Hopeworks or the Neighborhood Center were formed to facilitate Camden's movement into the 21st century.[30]

Due to its location as county seat, as well as its proximity to Philadelphia, Camden has had strong connections with its neighboring city.

On July 17, 1951, the Delaware River Port Authority, a bi-state agency, was created to promote trade and better coordinate transportation between the two cities.[131]

In June 2014, the Philadelphia 76ers announced that they would relocate their home offices and construct a 120,000-square-foot (11,000 m2) practice facility on the Camden Waterfront, adding 250 permanent jobs in the city creating what CEO Scott O'Neil described as "biggest and best training facility in the country" using $82 million in tax incentives offered by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority.[132]

The Battleship New Jersey, a museum ship located on the Delaware Waterfront, was a contested topic for the two cities. Philadelphia's DRPA funded millions of dollars into the museum ship project as well as the rest of the Waterfront, but the ship was originally donated to a Camden-based agency called the Home Port Alliance. They argue that Battleship New Jersey is necessary for Camden's economic growth.[133][134] As of October 2001, the Home Port Alliance has maintained ownership of Battleship New Jersey.

Black culture

In 1967, Charles 'Poppy' Sharp founded the Black Believers of Knowledge, an organization founded on the betterment of African American citizens in South Camden. He would soon rename his organization to the Black People's Unity Movement (BPUM). The BPUM was one of the first major cultural organizations to arise after the deindustrialization of Camden's industrial life. Going against the building turmoil in the city, Sharp founded BPUM on "the belief that all the people in our community should contribute to positive change."[30]

In 2001, Camden residents and entrepreneurs founded the South Jersey Caribbean Cultural and Development Organization (SJCCDO) as a non-profit organization aimed at promoting understanding and awareness of Caribbean Culture in South Jersey and Camden. The most prominent of the events that the SJCCDO organizes is the South Jersey Caribbean Festival, an event that is held for both cultural and economical reasons. The festival's primary focus is cultural awareness of all of Camden's residents. The festival also showcases free art and music as well as financial information and free promotion for Camden artists.[135]

In 1986, Tawanda 'Wawa' Jones began the Camden Sophisticated Sisters, a youth drill team. CSS serves as a self-proclaimed 'positive outlet' for the Camden' students, offering both dance lessons as well as community service hours and social work opportunities. Since its conception CSS has grown to include two other organizations, all ran through Jones: Camden Distinguished Brothers and The Almighty Percussion Sound drum line.[136] In 2013, CSS was featured on ABC's Dancing with the Stars.[137]

Hispanic and Latino culture

On December 31, 1987, the Latin American Economic Development Association (LAEDA). LAEDA is a non-profit economic development organization that helps with the creation of small business for minorities in Camden. LAEDA was founded under in an attempt to revitalize Camden's economy and provide job experience for its residents. LAEDA operates on a two major methods of rebuilding, The Entrepreneurial Development Training Program (EDTP) and the Neighborhood Commercial Expansion Initiative (NCEI). In 1990, LAEDA began a program called The Entrepreneurial Development Training Program (EDTP) which would offer residents employment and job opportunities through ownership of small businesses. The program over time created 506 businesses and 1,169 jobs. As of 2016, half of these businesses are still in operation. Neighborhood Commercial Expansion Initiative (NCEI) then finds locations for these business to operate in, purchasing and refurbishing abandoned real estate. As of 2016 four buildings have been refurbished including the First Camden National Bank & Trust Company Building.[138]

One of the longest-standing traditions in Camden's Hispanic community is the San Juan Bautista Parade, a celebration of St. John the Baptist, conducted annually starting in 1957. The parade began in 1957 when a group of parishioners from Our Lady of Mount Carmel marched with the church founder Father Leonardo Carrieri. This march was originally a way for the parishioners to recognize and show their Puerto Rican Heritage, and eventually became the modern day San Juan Bautista Parade. Since its conception, the parade has grown into the Parada San Juan Bautista, Inc, a non-for-profit organization dedicated to maintaining the community presence of Camden's Hispanic and Latino members. Some of the work that the Parada San Juan Bautista, Inc has done include a month long event for the parade with a community commemorative mass and a coronation pageant. The organization also awards up to $360,000 in scholarships to high school students of Puerto Rican descent.[139]

On May 30, 2000, Camden resident and grassroots organizer Lillian Santiago began a movement to rebuild abandoned lots in her North Camden neighborhood into playgrounds. The movement was met with resistance from the Camden government, citing monetary problems. As Santiago's movement gained more notability in her neighborhoods she was able to move other community members into action, including Reverend Heywood Wiggins. Wiggins was the president of the Camden Churches Organized for People, a coalition of 29 churches devoted to the improvement of Camden's communities, and with his support Santiago's movement succeeded. Santiago and Wiggins were also firm believers in Community Policing, which would result in their fight against Camden's corrupt police department and the eventual turnover to the State government.[140]

Arts and entertainment

Camden has two generally recognized neighborhoods located on the Delaware River waterfront, Central and South. The Waterfront South was founded in 1851 by the Kaighns Point Land Company. During World War Two, Waterfront South housed many of the industrial workers for the New York Shipbuilding Company. Currently, the Waterfront is home to many historical buildings and cultural icons. The Waterfront South neighborhood is considered a federal and state historic area due to its history and culturally significant buildings, such as the Sacred Heart Church, and the South Camden Trust Company[141] The Central Waterfront is located adjacent to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and is home to the Nipper Building (also known as The Victor), the Adventure Aquarium, and Battleship New Jersey, a museum ship located at the Home Port Alliance.

Starting on February 16, 2012, Camden's Waterfront began an art crawl and volunteer initiative called Third Thursday in an effort to support local Camden business and restaurants.[142] Part of Camden's art crawl movement exists in Studio Eleven One, a fully restored 1906 firehouse opened in 2011 that operated as an art gallery owned by William and Ronja Butlers. The Butlers moved to Camden in 2011 from Des Moines, Iowa and began the Third Thursday art movement. William Butler and Studio Eleven One are a part of his wife's company Thomas Lift LLC, self described as a "socially conscious company" that works to connect Camden's art scene with philanthropic organizations. Some of the work they have done includes work against Human Trafficking, and ecological donations.[143]

Starting in 2014, Camden began Connect The Lots, a community program designed to revitalize unused areas for community engagement. Connect the Lots was founded through The Kresge Foundation, and the project "seeks to create temporary, high-quality, safe outdoor spaces that are consistently programmed with local cultural and recreational activities". Other partnerships with the Connect the Lots foundation include the Cooper's Ferry Partnership, a private non-profit corporation dedicated to urban renewal. Connect the Lots' main work are their 'Pop up Parks' that they create around Camden. In 2014, Connect the lots created a pop up skate park for Camden youth with assistance from Camden residents as well as students. As of 2016, the Connect the Lots program free programs have expanded to include outdoor yoga and free concerts.[37]

In October 2014, Camden finished construction of the Kroc Center, a Salvation Army funded community center located in the Cramer Hill neighborhood. The Kroc center's mission is to provide both social services to the people of Camden as well as community engagement opportunities. The center was funded by a $59 million donation from Joan Kroc, and from the Salvation Army. The project was launched in 2005 with a proposed completion date of one year. However, due to the location of the site as well as governmental concerns, the project was delayed. The Kroc center's location was an 85-acre former landfill which closed in 1971. Salvation Army Major Paul Cain states the landfill's location to the waterfront and the necessity to handle storm water management as main reasons for the delay. The center was eventually opened on October 4, 2014, with almost citywide acclaim. Camden Mayor Dana Redd on the opening of the center called it "the crown jewel of the city."[144] The Kroc Center offers an 8-lane, 25-yard competition pool, a children's water park, various athletic and entertainment options, as well as an in center chapel.

The Symphony in C orchestra is based at Rutgers University-Camden. Established as the Haddonfield Symphony in 1952, the organization was renamed and relocated to Camden in 2006.[145]

Philanthropy

Camden has a variety of non-profit Tax-Exempt Organizations aimed to assist city residents with a wide range of health and social services free or reduced charge to residents. Camden City, having one of the highest rates of poverty in New Jersey, fueled residents and local organizations to come together and develop organizations aimed to provide relief to its citizens. As of the 2000 Census, Camden's income per capita was $9,815. This ranking made Camden the poorest city in the state of New Jersey, as well as one of the poorest cities in the United States.[146] Camden also has one of the highest rates of childhood poverty in the nation.[146]

Camden was once a thriving industrialized city home to the RCA Victor, Campbell Soup Company and containing one of the largest shipping companies. Camden's decline stemmed from the lack in jobs once these companies moved over seas. Many of Camden's non-profit Organizations emerged during the 1900s when the city suffered a large decline in jobs which affected the city's growth and population. These organizations are located in all Camden sub-sections and offer free services to all city residents in an attempt to combat poverty and aid low income families. The services offered range from preventive health care, homeless shelters, early childhood education, to home ownership and restoration services. Nonprofits in Camden strive to assist Camden residents in need of all ages, from children to the elderly. Each nonprofit organization in Camden has an impact on the community with specific goals and services. These organizations survive through donations, partnerships, and fundraising. Volunteers are needed at many of these organizations to assist with various programs and duties. Camden's nonprofits also focus on development, prevention, and revitalization of the community. Nonprofit organizations serve as resource for the homeless, unemployed, or financially insufficient.

One of Camden's most prominent and longest running organizations with a span of 103 years of service, is The Neighborhood Center located in the Morgan Village section of Camden.[147] The Neighborhood Center was founded in 1913 by Eldridge Johnson, George Fox Sr., Mary Baird, and local families in the community geared to provide a safe environment for the city's children.[148] The goal of Camden's Neighborhood Center is to promote and enable academic, athletic and arts achievements. The Neighborhood Center was created to assist the numerous families living in Camden in poverty. The Neighborhood Center also has an Urban Community Garden as of the year 2015. Many of the services and activities offered for the children are after school programs, and programs for teenagers are also available.[149] These teenage youth programs aim to guide students toward success during and after their high school years. The activities at the Neighborhood Center are meant to challenge youth in a safe environment for fun and learning. These activities are developed with the aim of The Neighborhood Center helping to break the cycle of poverty that is common in the city of Camden.

Center for Family Services Inc[150] offers a number of services and programs that total 76 free programs. This organization has operated in South Jersey for over 90 years and is one of the leading non-profits in the city. Cure4Camden is a community ran program focused on stopping the spread of violence in Camden and surrounding communities. They focus on stopping the spread of violence in the Camden City communities of:

- Liberty Park

- Whitman Park

- Centerville

- Cooper Plaza/Lanning Square

Center for Family Services offers additional programs such as: Active parenting and Baby Best Start program, Mental Health & Crisis Intervention, and Rehabilitative Care. They are located at 584 Benson St Camden NJ 801[151] Center for Family Services is a nonprofit organization helping adults, children, and families. Center for Family Services' main focus is "prevention." Center for Family Services has over 50 programs, aimed at the most "vulnerable" members of the community.[152] These programs are made possible by donors, a board of trustees, and a professional staff. Their work helps prevent possible victims of abuse, neglect, or severe family problems. Their work helps thousands of people in the community and also provides intervention services to individuals and families. Their programs for children are home-based, community-based, as well as school-based.[152] Center for Family Services is funded through partners, donors, and funders from the community and elsewhere.

Cathedral Soup Kitchen, Inc.[153] is a Human Service-based non-profit Organization that is the largest emergency food distribution agency in Camden. The organization was founded in 1976 by four Camden residents after attending a lecture given by Mother Theresa. They ran off of donated food and funds for fourteen years until they were granted tax exempt status as a 501(c) (3) corporation in 1990. In the 1980s, a new program started at The Cathedral Kitchen called the "casserole program", which consisted of volunteers cooking and freezing casseroles to be donated and dropped off at the Cathedral Kitchen, and then be served to guests.[154] Cathedral Kitchen faced many skeptics at first, despite the problems they were attempting to solve in the community, such as hunger. The Cathedral Kitchen's first cooking staff consisted of Clyde and Theresa Jones. Next, Sister Jean Spena joined the crew and the three members ran cooking operations over the course of several years.[154] They provide 100,000 meals a year and launched a Culinary Arts Catering[152] program in 2009. They provide hot meals Monday through Saturday to Camden County residents. The Cathedral Kitchen's annual revenue is $3,041,979.00.[155]

A fundraising component of the Cathedral Kitchen is CK Cafe. CK Cafe is a small lunch restaurant used by the Cathedral Kitchen to provide employment to those who graduate from their programs as well as generate profits to continue to provide food to the hungry.[156] CK Cafe is open Monday through Friday from 11:00 am to 2:00 pm. You can even place an order for takeout by calling their telephone number. CK Cafe even offers catering and event packages. The Cathedral Kitchen is innovative and unique compared to other soup kitchens, because those who eat at The Cathedral Kitchen are referred to as "dinner guests" rather than the homeless, the hungry, etc.[157] The Cathedral Kitchen also offers various opportunities for those interested to volunteer. Another feature of The Cathedral Kitchen is their free health clinics with a variety of services offered including dental care and other social services.[157]

Catholic Charities of Camden, Inc. is a faith-based organization which advocates and uplifts the lives of the poor and unemployed.[158] They provide services in six New Jersey counties and serve over 28,000 people each year. The extent of the services offered exceed those of any of Camden's other Non- Profit Organizations. Catholic Charities Refugee[159]

Camden Churches Organized for People (CCOP) is an arrangement between various congregations of Camden to partner together against problems in the community.[160] CCOP is affiliated with Pacific Institute for Community Organization (PICO). CCOP is a non-religious, non-profit organization that works with believers in the Camden to solve social problems in the community. Their beliefs and morals are the foundation for their efforts to solve a multitude of problems in the Camden community. CCOP's system for community organizing was modeled after PICO, which stresses the importance of social change instead of social services when addressing the causes of residents and their families' problems. CCOP's initial efforts began in 1995, and was composed only of two directors and about 60 leaders from the 18 churches in the organization.[146]

The congregation leaders of CCOP all had a considerable number of networking contacts but were also looking to expand and share their networking relationship with others.[146] CCOP congregation leaders also had to listen to the concerns of those in their networking contacts, the community, and the congregations. One of the main services of CCOP was conducting one-on-one's with people in the community, to recognize patterns of residents' problems in the community.[146]

Cooper Grant Neighborhood Association is located in the historic Cooper Grant neighborhood that once housed William Cooper, an English Quaker with long ties to Camden.[161] His son Richard Cooper[162] along with his four children are responsible for contributing to the creation of the Cooper Health System.[163] This organizations goal is to enrich the lives of citizens living in the Cooper Grant neighborhood located from the Camden Waterfront up to Rutgers University Camden campus. This center offers community service to the citizens living in the historic area that include activism, improving community health and involvement, safety and security, housing development, affordable childcare services, and connecting neighborhoods and communities together. The Cooper Grant Neighborhood Association owns the Cooper Grant Community Garden.[164] Project H.O.P.E organization offers healthcare to the homeless, preventive health Care, substance abuse programs, social work services, behavioral health care.[165]

The Heart of Camden Organization offers home renovation and restoration services and home ownership programs. Heart of Camden receives donations from online shoppers through Amazon Smile.[166] Heart of Camden Organization is partners with District Council Collaborative Board (DCCB).[167] Heart of Camden Organization's accomplishments include the economic development of various entities such as the Waterfront South Theatre, Neighborhood Greenhouse, and a community center with a gymnasium. Another accomplishment of Heart of Camden Organization is its revitalization of Camden, which includes Liney's Park Community Gardens and Peace Park.[168]

Fellowship House of South Camden is an organization that offers Christian (Nondenominational) based after school and summer programs.[169] Fellowship House was founded in 1965 and started as a weekly Bible club program for students in the inner-city of Camden. Settlement was made on a house located at Fellowship House's current location in the year 1969.[170] Fellowship House hired its first actual staff member, director Dick Wright, in the year 1973.

VolunteersofAmerica.org[171] helps families facing poverty and is a community based organization geared toward helping families live self-sufficient, healthy lives. With a 120 years of service the Volunteers of America has dedicated their services to all Americans in need of help. Home for the Brave[172] is a housing program aimed to assist homeless veterans. This program is a 30-bed housing program that coincides with the Homeless Veterans Reintegration program which is funded through the Department of Labor. Additional services include; Emergency Support, Community Support, Employment Services, Housing Services, Veterans Services, Behavioral Services, Senior Housing.

The Center for Aquatic Sciences was founded in 1989 and continues to promote its mission of: "education and youth development through promoting the understanding, appreciation and protection of aquatic life and habitats."[173] In performing this mission, the Center strives to be a responsible member of the community, assisting in its economic and social redevelopment by providing opportunities for education, enrichment and employment. Education programs include programs for school groups in our on-site classrooms and aquarium auditorium as well as outreach programs throughout the Delaware Valley. The center also partners with schools in both Camden and Philadelphia to embed programs during the school day and to facilitate quality educational after-school experiences.

Research and conservation work includes an international program, where the center has studied and sought to protect the threatened Banggai cardinalfish and its coral reef habitat in Indonesia. This work has resulted in the Banggai cardinalfish being included as an endangered species on IUCN Red List of Threatened and Endangered Species, the FIRST saltwater aquarium fish to be listed as endangered in the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA), the publication of The Banggai Cardinalfish: Natural History, Conservation, and Culture of Pterapogon kauderni, and numerous peer review journal articles.[174]

The center's flagship program is CAUSE (Community and Urban Science Enrichment).[175] CAUSE is a many-faceted science enrichment program for children and youth. The program, initiated in 1993, has been extremely successful, boasting a 100% high school graduation rate and a 98% college enrollment rate, and has gained local and regional attention as a model for comprehensive, inner-city youth development programs, focusing on intense academics and mentoring for a manageable number of youth.

Economy

About 45% of employment in Camden is in the "eds and meds" sector, providing educational and medical institutions.[33]

Largest employers

- Campbell Soup Company

- Cooper University Hospital

- Delaware River Port Authority

- L3 Technologies, formerly L-3 Communications

- Our Lady of Lourdes Medical Center

- Rutgers University–Camden

- State of New Jersey

- New Jersey Judiciary

- Subaru of America; relocated from suburban Cherry Hill in 2018

- Susquehanna Bank

- UrbanPromise Ministry (largest private employer of teenagers)

Urban enterprise zone

Portions of Camden are part of a joint Urban Enterprise Zone. The city was selected in 1983 as one of the initial group of 10 zones chosen to participate in the program.[176] In addition to other benefits to encourage employment within the Zone, shoppers can take advantage of a reduced 3.3125% sales tax rate (half of the 6.625% rate charged statewide) at eligible merchants.[177] Established in September 1988, the city's Urban Enterprise Zone status expires in December 2023.[178]

The UEZ program in Camden and four other original UEZ cities had been allowed to lapse as of January 1, 2017, after Governor Chris Christie, who called the program an "abject failure", vetoed a compromise bill that would have extended the status for two years.[179] In May 2018, Governor Phil Murphy signed a law that reinstated the program in these five cities and extended the expiration date in other zones.[180]

Redevelopment

The state of New Jersey has awarded more than $1.65 billion in tax credits to more than 20 businesses through the New Jersey Economic Opportunity Act. These companies include Subaru, Lockheed Martin, American Water, EMR Eastern and Holtec.[181]

Campbell Soup Company decided to go forward with a scaled-down redevelopment of the area around its corporate headquarters in Camden, including an expanded corporate headquarters.[182] In June 2012, Campbell Soup Company acquired the 4-acre (1.6 ha) site of the vacant Sears building located near its corporate offices, where the company plans to construct the Gateway Office Park, and razed the Sears building after receiving approval from the city government and the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection.[183]

In 2013, Cherokee Investment Partners had a plan to redevelop north Camden with 5,000 new homes and a shopping center on 450 acres (1.8 km2). Cherokee dropped their plans in the face of local opposition and the slumping real estate market.[184][185][186] They are among several companies receiving New Jersey Economic Development Authority (EDA) tax incentives to relocate jobs in the city.[187][188][189]

Lockheed Martin was awarded $107 million in tax breaks, from the Economic Redevelopment Agency, to move to Camden. Lockheed rents 50,000 square feet of the L-3 communications building in Camden. Lockheed Martin invested $146.4 million into their Camden Project According to the Economic Redevelopment Agency. Lockheed stated that without these tax breaks they would have had to eliminate jobs.[190]

In 2013 Camden received $59 million from the Kroc estate to be used in the construction of a new community center and another $10 million was raised by the Salvation Army to cover the remaining construction costs. The Ray and John Kroc Corps Community Center, opened in 2014, is a 120,000 square foot community center with an 8,000 square foot water park and a 60 ft ceiling. The community center also contains a food pantry, a computer lab, a black box theater, a chapel, two pools, a gym, an outdoor track and field, a library with reading rooms, and both indoor and outdoor basketball courts.[191]

In 2015 Holtec was given $260 million over the course of 10-year to open up a 600,000-square-foot campus in Camden. Holtec stated that they plan to hire at least 1000 employees within the first year of them opening their doors in Camden. According to the Economic Development Agency, Holtec is slated to bring in $155,520 in net benefit to the state by moving to Camden, but in this deal, Holtec has no obligation to stay in Camden after its 10-year tax credits run out.[192] Holtec's reports stated that the construction of the building would cost $260 million which would be equivalent to the tax benefits they received.[193]

In fall 2017 Rutgers University Camden Campus opened up their Nursing and Science Building. Rutgers spent $62.5 million[194] to build their 107,000-square-foot building located at 5th and Federal St. This building houses their physics, chemistry, biology and nursing classes along with nursing simulation labs.[195]

In November 2017, Francisco "Frank" Moran was elected as the 48th Mayor of Camden. Prior to this, one of Moran's roles was as the director of Camden County Parks Department where he was in charge of overseeing several park projects expanding the Camden County Park System, including the Cooper River Park, as well as bringing back public ice skating rinks to the parks in Camden County.[196]

Moran has helped in bringing several companies to Camden, including Subaru of America, Lockheed Martin, Philadelphia 76ers, Holtec International, American Water, Liberty Property Trust, as well as EMR.[196]

Moran has also assisted with the public schools of Camden by supplying them with new resources, such as new technology for the classrooms, as well as new facilities.[196]

American Water was awarded $164.2 million in tax credits from the New Jersey's Grow New Jersey Assistance Program to build a five-story 220,000-square-foot building at Camden's waterfront. American Water opened this building in December 2018 becoming the first in a long line of new waterfront attractions planned to come to Camden.[197]

The NJ American Water Neighborhood Revitalization Tax Credit is a $985,000 grant which was introduced in July 2018. It is part of $4.8 million that New Jersey American Water has invested in Camden. Its purpose will be to allow current residents to remain in the city by providing them with $5,000 grants to make necessary home repairs. Some of the funding will also go towards Camden SMART (Stormwater Management and Resource Training). Funding will also go towards the Cramer Hill NOW Initiative, which focuses on improving infrastructure and parks.[198]

On June 5, 2017, Cooper's Poynt Park was completed. The 5-acre park features multi-use trails, a playground, and new lighting. Visitors can see both the Delaware River and the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Prior to 1985, the land the park resides on was open space that allowed Camden residents access to the waterfront. In 1985, the Riverfront State Prison was built, blocking that access. The land become available for the park to be built when the prison was demolished in 2009. Funding for the park was provided by Wells Fargo Regional Foundation, the William Penn Foundation, the State Department of Community Affairs, the Fund for New Jersey, and the Camden Economic Recovery Board.[199]

Cooper's Ferry Partnership is a private non-profit founded in 1984. It was originally known as Cooper's Ferry Association until it merged with the Greater Camden Partnership in 2011, becoming Cooper's Ferry Partnership. Kris Kolluri is the current CEO. In a broad sense, their goal is to identify and advance economic development in Camden. While this does include housing rehabilitation, Cooper's Ferry is involved in multiple projects. This includes the Camden Greenway, which is a set of hiking and biking trails, and the Camden SMART (Stormwater Management and Resource Training) Initiative.[200]

In January 2019, Camden received a $1 million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies for A New View, which is a public art project seeking to change illegal dump sites into public art fixtures. A New View is part of Bloomberg Philanthropies larger Public Art Challenge. Additionally, the program will educate residents of the harmful effects of illegal dumping. The effort will include the Cooper's Ferry Partnership, the Rutgers-Camden Center for the Arts, the Camden Collaborative Initiative, and the Camden City Cultural and Heritage Commission, as well as local businesses and residents. Locations to be targeted include dumping sites within proximity of Port Authority Transit Corporation high speed-line, the RiverLine, and the Camden GreenWay. According to Mayor Francisco Moran, illegal dumping costs Camden more than $4 million each year.[201][202][203]

Housing

Saint Joseph's Carpenters Society

Saint Josephs Carpenter Society (SJCS) is a 501c(3) non-profit organization located in Camden. Pilar Hogan is the current executive director. Their focus is on the rehabilitation of current residences, as well as the creation of new low income, rent-controlled housing. SJCS is attempting to tackle the problem of abandoned properties in Camden by tracking down the homeowners, so they can then purchase and rehabilitate the property. Since the organizations beginning, it has overseen the rehabilitation or construction of over 500 homes in Camden.[204]

SJCS also provides some education and assistance in the home-buying process to prospective homebuyers in addition to their rehabilitation efforts. This includes a credit report analysis, information on how to establish credit, and assistance in finding other help for the homebuyers.[205]

In March 2019, SJCS received $207,500 in federal funding from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development's (HUD) NeighborWorks America program. NeighborWorks America is a public non-profit created by Congress in 1978, which is tasked with supporting community development efforts at the local level.

Mount Laurel Doctrine

The Mount Laurel doctrine stems from a 1975 court case, Southern Burlington County N.A.A.C.P. v. Mount Laurel Township (Mount Laurel I). The doctrine was an interpretation of the New Jersey State Constitution, and states that municipalities may not use their zoning laws in an exclusionary manner to make housing unaffordable to low and moderate income people. The court case itself was a challenge to Mount Laurel specifically, in which plaintiffs claimed that the township operated with the intent of making housing unaffordable for low and moderate income people. The doctrine is more broad than the court case, covering all New Jersey municipalities.

Failed redevelopment projects

In early 2013, ShopRite announced that they would open the first full-service grocery store in Camden in 30 years, with plans to open their doors in 2015.[206] In 2016 the company announced that they no longer planned to move to Camden leaving the plot of land on Admiral Willson Boulevard barren and the 20-acre section of the city as a food desert.[207]

In May 2018, Chinese company Ofo brought its dockless bikes to Camden, along with many other cities, for a six-month pilot in an attempt to break into the American market. After two months in July 2018 Ofo decided to remove its bikes from Camden as part of a broader pullout from most of the American cities they had entered due to a decision that it was not profitable to be in these American cities.[208]

On March 28, 2019, a former financial officer for Hewlett-Packard, Gulsen Kama, alleged that the company received a tax break based on false information. The company qualified for a $2.7 million tax break from the Grow NJ incentive of the Economic Development Authority (EDA). Kama testified that the company qualified for the tax break because of a false cost-benefit analysis she was ordered to prepare. She claims the analysis included a plan to move to Florida that was not in consideration by the company. The Grow NJ Incentive has granted $11 billion in tax breaks to preserve and create jobs in New Jersey, but it has experienced problems as well. A state comptroller sample audit ordered by Governor Phil Murphy showed that approximately 3,000 jobs companies listed with the EDA do not actually exist. Those jobs could be worth $11 million in tax credits. The audit also showed that the EDA did not collect sufficient data on companies that received tax credits.[209]

Government

Camden has historically been a stronghold of the Democratic Party. Voter turnout is very low; approximately 19% of Camden's voting-age population participated in the 2005 gubernatorial election.[210]

Local government

Since July 1, 1961, the city has operated within the Faulkner Act, formally known as the Optional Municipal Charter Law, under a Mayor-Council form of government.[4] The city is one of 71 of 565 municipalities statewide that use this form of government.[211] The City Council is comprised of seven council members originally all elected at-large. In 1994, the city was divided into four council districts instead of electing the entire Council at-large, with a single council member elected from each of the four districts and three council members being elected at-large. In 1995, the elections were changed from a partisan vote to a non-partisan system, with elections still held as part of the November general election.[212]

As of 2020, the Mayor of Camden is Democrat Francisco "Frank" Moran, whose term of office ends December 31, 2021.[5] Members of the City Council are Council President Curtis Jenkins (D, 2021; at large), Vice President Marilyn Torres (D, 2023; Ward 3), Shaneka Boucher (D, 2023; Ward 1), Victor Carstarphen (D, 2023; Ward 2), Sheila Davis (D, 2021; at large), Angel Fuentes (D, 2021; at large) and Felisha Reyes-Morton (D, 2023; Ward 4).[213][214][215][216]

In February 2019, Felisha Reyes-Morton was unanimously appointed to fill the Ward 4 seat expiring in December 2019 that became vacant following the resignation of Council Vice President Luis A. Lopez the previous month, after serving ten years in office.[217]

In November 2018, Marilyn Torres was elected to serve the balance of the Ward 3 seat expiring in December 2019 that was vacated by Francisco Moran when he took office as mayor the previous January.[218]

In February 2016, the City Council unanimously appointed Angel Fuentes to fill the at-large term ending in December 2017 that was vacated by Arthur Barclay when he took office in the New Jersey General Assembly in January 2016; Fuentes had served for 16 years on the city council before serving in the Assembly from 2010 to 2015.[219] Fuentes was elected to another four-year term in November 2017.[216]

Mayor Milton Milan was jailed for his connections to organized crime. On June 15, 2001, he was sentenced to serve seven years in prison on 14 counts of corruption, including accepting mob payoffs and concealing a $65,000 loan from a drug kingpin.[220]

In 2018, the city had an average residential property tax bill of $1,710, the lowest in the county, compared to an average bill of $6,644 in Camden County and $8,767 statewide.[221][222]

Federal, state and county representation

Camden is located in the 1st Congressional District[223] and is part of New Jersey's 5th state legislative district.[12][224][225]

For the 116th United States Congress, New Jersey's First Congressional District is represented by Donald Norcross (D, Camden).[226][227] New Jersey is represented in the United States Senate by Democrats Cory Booker (Newark, term ends 2021)[228] and Bob Menendez (Paramus, term ends 2025).[229][230]

For the 2018–2019 session (Senate, General Assembly), the 5th Legislative District of the New Jersey Legislature is represented in the State Senate by Nilsa Cruz-Perez (D, Barrington) and in the General Assembly by Patricia Egan Jones (D, Barrington) and William Spearman (D, Camden).[231][232] Spearman took office in June 2018 followingh the resignation of Arthur Barclay.[233]

Camden County is governed by a Board of Chosen Freeholders, whose seven members chosen at-large in partisan elections to three-year terms office on a staggered basis, with either two or three seats coming up for election each year.[234] As of 2018, Camden County's Freeholders are Freeholder Director Louis Cappelli Jr. (D, Collingswood, term as freeholder ends December 31, 2020; term as director ends 2018),[235] Freeholder Deputy Director Edward T. McDonnell (D, Pennsauken Township, term as freeholder ends 2019; term as deputy director ends 2018),[236] Susan Shin Angulo (D, Cherry Hill, 2018),[237] William F. Moen Jr. (D, Camden, 2018),[238] Jeffrey L. Nash (D, Cherry Hill, 2018),[239] Carmen Rodriguez (D, Merchantville, 2019)[240] and Jonathan L. Young Sr. (D, Berlin Township, 2020).[241][234]

Camden County's constitutional officers, all elected directly by voters, are County clerk Joseph Ripa (Voorhees Township, 2019),[242][243] Sheriff Gilbert "Whip" Wilson (Camden, 2018)[244][245] and Surrogate Michelle Gentek-Mayer (Gloucester Township, 2020).[246][247][248] The Camden County Prosecutor is Mary Eva Colalillo.[249][250]

Political corruption

Three Camden mayors have been jailed for corruption: Angelo Errichetti, Arnold Webster, and Milton Milan.[251]

In 1981, Errichetti was convicted with three others for accepting a $50,000 bribe from FBI undercover agents in exchange for helping a non-existent Arab sheikh enter the United States.[252] The FBI scheme was part of the Abscam operation. The 2013 film American Hustle is a fictionalized portrayal of this scheme.[253]

In 1999, Webster, who was previously the superintendent of Camden City Public Schools, pleaded guilty to illegally paying himself $20,000 in school district funds after he became mayor.[254]