Black Belt in the American South

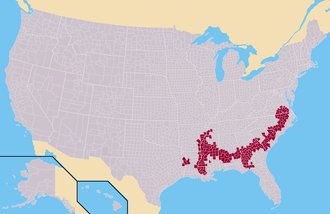

The Black Belt in the American South refers to the social history, especially concerning slavery and black workers, of the geological region known as the Black Belt. The geology emphasizes the highly fertile black soil. Historically, the black belt economy was based on cotton plantations – along with some tobacco plantation areas along the Virginia-North Carolina border. The valuable land was controlled by rich whites, and worked by very poor primarily black labor. After 1945, a large fraction of the laborers were replaced by machinery, and they joined the Great Migration to faraway cities. Diversified agriculture replaced much of the cotton and tobacco.[1][2] Political analysts and historians continue to use the term to designate heavily black rural areas in the Deep South in the United States.

| Part of a series on | ||||||||||||

| African Americans | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Religion

|

||||||||||||

|

Politics

|

||||||||||||

|

Civic / economic groups

|

||||||||||||

|

Sports

|

||||||||||||

|

Sub-communities

|

||||||||||||

|

Dialects and languages

|

||||||||||||

|

Population

|

||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Definitions

By 1894, political commentators used the term "Black Belt" so often that the term was already very well known in the United States. The Nation reported in 1894:

- There are 12 counties in Alabama in each of which the Blacks are twice as numerous as the whites. These 12 counties, stretching across southern Central Alabama from Georgia and Mississippi, constitute the principal portion of the famous Black Belt.[3]

By 1900 popular usage used "Black Belt" to denote a geopolitical region, much like later coinages such as snow belt, rust belt, sun belt and bible belt. Booker T. Washington wrote in his 1901 autobiography[4]

I have often been asked to define the term "Black Belt." So far as I can learn, the term was first used to designate a part of the country which was distinguished by the colour of the soil. The part of the country possessing this thick, dark, and naturally rich soil was, of course, the part of the South where the slaves were most profitable, and consequently they were taken there in the largest numbers. Later, and especially since the war, the term seems to be used wholly in a political sense—that is, to designate the counties where the black people outnumber the white.

The boundaries of the subregion depends on the exact criteria being used. Census data is used to identify rural Southern counties with a large black population in a particular year. Which percentage and which year depends on the goals of the project--to look at history, or at current patterns, or to project future trends. In 1980, Southern counties with at least 25 percent African-American populations comprised 29 percent of the Southern United States' population, falling to 23 percent in 2005. The white population in the same counties fell from 23 percent to 17 percent. In total numbers, these counties included 6,700,000 blacks in 1980, and 8,400,000 in 2005. They included 10,700,000 whites in 1980 and 11,700,000 in 2005.[5]

Prior to the large shift of the Second Great Migration of many rural blacks out of the region the 1940s to the 1960s, the sociologist Arthur Raper described the Black Belt of 1936 as some 200 plantation counties where blacks represented more than 50% of the population, lying "in a crescent from Virginia to Texas".[6] The University of Alabama also classifies "roughly 200 counties" as comprising the Black Belt.[7]

Political activists and historians continue to use "Black Belt" in considering politics in heavily black rural areas in the South. For example, in 1962, Martin Luther King wrote of his "People to People" tour through the Black Belt of Virginia: "The idea of "massive resistance" was spawned not in Georgia or Alabama—–but in the hearts of the Southside Virginia, commonly known as the Black Belt." [8] In 1964 King met with black leaders in to find a target locale to publicize the civil rights movement in Alabama. Large cities were eliminated, so according to historian Charles S. Aiken, "King had only the state's small nonmetropolitan cities from which to select the place to focus the campaign for new voting rights legislation.... There was no other choice but the "open spaces" of the Black Belt, and in the Black Belt there was no alternative to Selma."[9] In 2012, political scientist Seth McKee concluded that in the 1964 election, "Once again, the high level of support for Goldwater in the Deep South, and especially their Black Belt counties, spoke to the enduring significance of white resistance to black progress."[10]

Political power

The "Redeemers", a Southern Democratic political coalition that sought to enforce white supremacy,[11] came to power after Reconstruction ended in 1877 and ousted Black Republicans from political office across the South. Historian Edward L. Ayers argues the Redeemers were sharply divided however, and fought for control of the Democratic Party:

For the next few years the Democrats seemed in control of the South, but even then deep challenges were building beneath the surface. Behind their show of unity, the Democratic Redeemers suffered deep divisions. Conflicts between upcountry and Black Belt, between town and country, and between former Democrats and former Whigs divided the Redeemers. The Democratic party proved too small to contain the ambitions of all the white men who sought its rewards, too large and unwieldy to move decisively.[12]

During the period of disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction Era, mainly the years 1890–1907, new state constitutions and state laws, and informal local practices across the South were deliberately used to prevent African-American citizens from registering to vote and voting. States became one-party Democratic bastions in which the general election was a formality. The real battles took place inside the Democratic Party primaries, which were legally private and not open to blacks. The result was to thwart the objective of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which sought to protect the suffrage of freedmen after the American Civil War. Congress did not object, and the Supreme Court generally approved.[13] The mostly black Republican Party almost never won any elections in the Black Belt, but it did send delegates to the presidential nominating conventions every four years, thus giving blacks some voice in national politics. President William Howard Taft used this device to defeat ex-President Theodore Roosevelt for the GOP nomination in 1912.[14][15][16]

After 1900, African Americans, the majority of the population in most of the Black Belt, were rarely allowed to vote, apart from a few ministers, businessmen and schoolteachers. Political power was in the hands of a relatively closed white elite comprising the major landowners, along with local merchants and bankers. They had almost complete control of local government. Generally they also had control of the state legislatures, which gerrymandered political districts to heavily favor rural areas and under-represent the cities.[17] By the 1950s each county had a local Citizens' Council (the groups were commonly referred to as the "White Citizens' Councils") which was part an associated network of white supremacist, extreme right[18] organizations that directed white resistance to racial integration, especially to integrating the public schools.[19][20] Federal intervention changed the situation in the 1970s. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was strictly enforced, allowing everyone to vote,[21] and the Supreme Court imposed a one-man-one vote rule about the same time that shifted power toward the urban South.

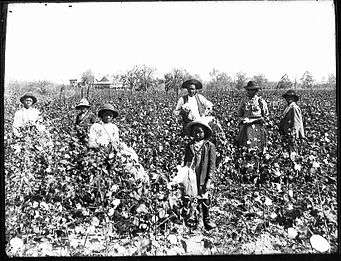

Tenant farming

Until the mid-20th century, the predominant agricultural system in the Black Belt involved interdependent white land owners, tenant farmers, and sharecroppers; most of the latter groups were African-Americans. Tenants typically owned their own tools and work animals while the sharecroppers provided no capital and paid fees with crops—[22]very little money changed hands. The few existing local banks were small; cash was scarce and had to be saved by the landowners for paying taxes. The early 1920s were especially hard in cotton regions as the price of cotton plunged from 37 cents per pound in early 1920 to 10 cents in mid-1921.[23] Land prices plunged 80% and tax rates went up.[24] Tenants could not repay the storekeepers. Land owners were squeezed, for many had used credit to buy land during the World War bubble; and many farms were foreclosed--all this before the Great Depression struck in 1929. Raper's analysis of Black Belt banks shows that deposits plunged by half or more from 1918 to 1932. As a result most local people became "very shy of banks." New Deal programs helped the land owners much more than the tenants.[25][26][27]

Landowners needed a great deal of labor at harvest time to pick cotton. The typical plan was to divide old plantations into small farms that were assigned to the tenants. Throughout the year the tenants every week bought food and supplies on credit through the local country store. At harvest time, the tenants picked and sold their cotton, paid the merchant and gave the landowner his one-third. There seldom was much cash left over. For sharecroppers the landlord supplied all the needs during the year and then took the crop. The annual cycle then started all over again, often with a large turnover of sharecroppers. Landowners also worked some of the land directly, using black labor paid in cash. The white landowners held all the political power, and fought vigorously against cash-dispensing government welfare programs that would undermine the cashless system. Economic historians Lee Alston and Joseph Ferrie (1999) describe the system as essentially an informal contract that bound employer and worker through the provision of housing, medical care, and other in-kind services along with cash wages. At its heart, it guaranteed a stable and adequate labor supply to the planter. Though restricted by the directives of the planter, workers in return received some measure of economic stability, including a social safety net, access to financial capital, and physical protection in an often violent society.[28]

There were few alternative jobs in the Black Belt region, and with the opening of factories to supply the war effort in World War II, as well as the introduction of the military draft, large numbers of African-American farmers left for the army or cash-paying jobs in nearby or distant cities. This population movement was called the Great Migration. With the beginning of the war, outbound migration increased significantly.[29] A decade after the end of the war, a practical combination of more efficient machinery and chemical herbicides finally became available to cotton planters, and a reduced need for resident farm labor led to even greater black emigration to the North.[30]

Quality of life

The Black Belt, with its largely African-American population, has historically ranked toward the bottom of American regions in terms of quality of life indicators such as poverty rates, median incomes, mortality, unemployment rates, and educational levels.[31] For example, transportation routes have historically been inadequate in this region before the 1950s, and to this day air transportation facilities are limited. [32]

Alabama

Religion

In the late 19th century, slavery in Alabama was centered in the Black Belt which ran across the central part of the state, mainly in Sumter, Greene, Hale, Perry, Marengo, Dallas, Wilcox, Lowndes, Montgomery, and Bullock counties.[33] Baptist membership grew rapidly in the Black Belt, from a total of 71,000 in 1890 (of whom 86 percent were African-American), rising to 215,000 in 1916.

White religion

The slave owners in the region were affluent, and typically belonged to the Presbyterian, Episcopalian, or Methodist churches. After the Civil War, many of the owners sold out and moved to distant cities. Presbyterian, and Episcopalian membership fell. Among the whites, Methodism grew and especially the Baptists churches grew rapidly. New fundamentalist sects, such as Holiness and Nazarene, began to appear but their rapid growth came after 1900. [34] In the white community, Baptist church services were typically held Sundays at 11 AM and 6 PM, with an earlier Sunday school for children. During the week there were prayer meetings and meetings of the ladies' society and missionary organizations. Smaller rural churches shared a rotating pastor and had a lighter schedule. Occasionally the Baptists would hold rallies promoting membership drives, domestic missions, Christian education, religious literature, prayer in the home, Christian citizenship, and one outside issue, laws to promote temperance. Until the late 19th century, the preachers continue to focus on the need for revivals, and Sabbath observance, on the evils of Catholicism, card playing, dancing and personal sin in general. Every few weeks the churches held trials of their own members for sins like drunkenness, dancing, or adultery; the usual participant punishment was humiliation or expulsion. The theology was traditional, with no trace of modernist readings of the Bible. Unlike the Methodists and Presbyterians very few Baptist pastors were educated. Instead, the local congregation selected and ordained ministers on the basis of their religiosity and ability to articulate God's word. By 1900, the range of sermons and editorials had been enlarged to cover new social themes. Baptists still opposed Catholicism, but now they talked of cooperation with other Protestant churches. There was less emphasis on card playing and dancing, and more interest in underpaid laborers, coal miners, and workers in sweatshops, indicative of a newfound interest in the Social Gospel, although not nearly at the level of Northern Protestant churches. Racial tensions and discrimination was not mentioned, nor the growing rate of lynchings[35]

Black religion

Many, probably most, slaves had become Christians during the antebellum period. Their religious preferences focused on evangelical religion with strong participation by the congregations, and led by a strong minister who typically was also a political leader. By 1867, freedmen, with help from the Freedmen's Bureau, began organizing their own separate all-black churches. Northern Methodist missionaries helped organize such churches as were affiliated with the national Methodist Church. More popular were the African African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, and the African Methodist Episcopal Church. White southern Methodists had a separate body, and they sponsored the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church. The Baptist churches were even more popular. Small numbers belonged to the Episcopalian and Presbyterian churches. All the Methodists had a hierarchical organization led by bishops. More democratic and more numerous were the locally based Baptist churches. At their first state convention in 1868, the 60 Baptists attending represented 32 churches. By 1881 the church had 50 district associations, 600 churches, 700 preachers, and about 90,000 members in the state, and operated a small seminary in Selma; most of the ministers were strong orators but barely literate. Although the revivalist camp meeting movement was fading away in the white churches, it grew more popular in the black community. In addition to all-day Sunday services, many Black Baptists became active in Sunday schools and missionary societies.[36][37]

Sharecropping

Although racial tensions often grew violent during the Reconstruction era (1863–1877), in the Alabama black belt a satisfactory compromise was reached through a sharecropping system in which local black farmers were under the protection of rich white landowners:

The strength of African-American activism and, to a lesser extent, the moderation of elite planters meant that in the black belt Reconstruction essentially worked. Sharecropping developed as a compromise that allowed white planters to make money while black workers preferred its relatively greater autonomy in comparison to slavery. As a result of the labor compromise that developed, the black belt saw less terroristic white supremacist violence than did northern Alabama. Fitzgerald’s work thus adds specific teeth to the arguments of Steven Hahn—and before him, W. E. B. Du Bois —about the political acumen and solidarity of rural African Americans. White planters obviously were at the top of economic and political ladders, but black tenant farmers were real agents of power.[38]

Georgia

Religion

William J. Northen (1835–1913), was the Governor of Georgia from 1890 to 1894. As well as a leading Baptist minister. Northen was president of the Georgia Baptist Convention from 1892 to 1910,[39] and president of the Southern Baptist Convention from 1899 to 1901.[40] His political rhetoric was based on his religious outlook, and often is focused on racial issues at a time when lynching was growing rapidly. Northen believed that advances in medicine and health would ultimately help African Americans achieve salvation. He promoted the ideology of the modernizing New South, but did not abandon the policy of white supremacy.[41]

Women

The study of women's history and gender roles in the black belt has been a recent development. Chrissy Lutz and Dawn Herd-Clark in 2019 explored the situation of black housewives in Georgia's black belt in the 1920s and 1930s, and how they worked with outside agencies to improve their own work efficiency and economic opportunities. Fort Valley State College, a historically black college, collaborated with the segregated unit of the Cooperative Extension Service, an educational arm of the United States Department of Agriculture. They trained and supplied black organizers, and set up and funded local clubs, and gave farm and home demonstrations. They focused on domestic chores that included cooking, hygiene, sewing, garden work, and poultry raising. Not only did they teach new skills, they helped isolated rural women to meet each other and form supportive friendships. The systematic end of rural isolation meant that black rural women could affirm that "no one was on their own."[42]

Collapse of the Black belt socio-economic plantation system

Economic historians of the South generally emphasize the continuity of the system of white supremacy and cotton plantations in the Black Belt from the late colonial era into the mid-20th century, when it collapsed. Harold D, Woodman summarizes the explanation that external forces caused the disintegration from the 1920s to the 1970s:

When significant change finally occurred, its impetus came from outside the South. Depression-bred New Deal reforms, war-induced demand for labor in the North, perfection of cotton-picking machinery, and civil rights legislation and court decisions finally...destroyed the plantation system, undermined landlord or merchant hegemony, diversified agriculture and transformed it from a labor- to a capital-intensive industry, and ended the legal and extralegal support for racism. The discontinuity that war, invasion, military occupation, the confiscation of slave property, and state and national legislation failed to bring in the mid nineteenth century finally arrived in the second third of the twentieth century.[43]

Historiography and memory

W. E. B. DuBois

The most prominent student of the Black Belt was sociologist W. E. B. DuBois, who engaged in statistically based studies of family life, economic cooperation, and social conditions as editor of The Atlantic University Publications in the early 20th century. His 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk contains extensive analysis and reflection.[44] Du Bois calls Albany, Georgia, in Dougherty County, the "heart of the Black Belt." He says: "Here are the remnants of the vast plantations."[45]

"How curious a land is this,- how full of untold story, of tragedy and laughter, and the rich legacy of human life; shadowed with a tragic past, and big with future promise!"

Yet, he notes, it is not far from "where Sam Hose was crucified" [in a lynching], "to-day the centre of the Negro problem,-the centre of those nine million men who are America's dark heritage from slavery and the slave-trade." He continues: "Careless ignorance and laziness here, fierce hate and vindictiveness there,—these are the extremes of the Negro problem which we met that day, and we scarce knew which we preferred."[46]

Restoration of old dwellings

Since the late 20th century, a recent development has been the restoration, preservation and historical analysis of African-American dwelling units in the Black Belt, especially those surviving from slavery days. Ashley A. Dumas, et al. explain the rationale:

Slave houses are artifacts. Their attributes can be recorded, analyzed, and broad patterns about their historical context, their builders, and inhabitants revealed. The methods of construction, for instance, often indicate climate, economy, and available technology. Ethnographic and archaeological studies demonstrate that houses, yards, and landscapes reflect cultural values and social relationships and changes to these. The organization of labor may be inferred from the placement of houses in relation to one another and to non-domestic buildings.[47]

See also

Notes

- University of Georgia. Institute for the Study of Georgia Problems (1950). Monograph. p. 15.

- D. Clayton Brown (2011). King Cotton in Modern America: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History since 1945. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-60473-799-8.

- "Politics and the race question in Alabama ,: The Nation Sept. 20, 1894, p. 211 online

- Washington, Booker T. (1901). Up From Slavery. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- Dale W. Wimberley, "Quality of Life Trends in the Southern Black Belt, 1980–2005: A Research Note*" Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25.1 (2010) pp. 108, 109.

- Arthur Raper, "The Black Belt", Southern Spaces, 2004

- "Black Belt Fact Book". University of Alabama. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- Martin Luther King (2014). The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. VII: To Save the Soul of America, January 1961 August 1962. Univ of California Press. p. 437. ISBN 978-0-520-28269-8.

- Charles S. Aiken, The Cotton Plantation South since the Civil War (1998) online p. 215.

- Seth C. McKee (Fall 2012). "The Past, Present, and Future of Southern Politics". Southern Cultures. UNC Press Books. 18 (3, The Politics Issue): 10.

- Michael Fellman (2010). In the Name of God and Country: Reconsidering Terrorism in American History. Yale University Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-300-15501-3.

- Edward L. Ayers (2007). The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction - 15th Anniversary Edition. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-988683-8.

- Michael Perman, Struggle for Mastery: Disfranchisement in the South, 1888–1908 (2001).

- Geoffrey Cowan, Let the People Rule: Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of the Presidential Primary (2016) pp. 3, 74, 81, 83, 163–69.

- Lewis L. Gould, "Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Disputed Delegates in 1912: Texas as a Test Case." Southwestern Historical Quarterly 80.1 (1976): 33–56 online.

- George N. Green, "Republicans, Bull Moose, and Negroes in Florida, 1912." Florida Historical Quarterly 43.2 (1964): 153–164 online

- V. O. Key, Southern Politics in State and Nation (1949) pp. 513-17.

- Lazar, Ernie (August 2016). "Finding Aid – FBI and Other Files (Ernie Lazar Collection)" (PDF). Berkeley Center for Right Wing Studies. The University of California – via Database.

- Jack M. Bloom (1987). Class, Race, and the Civil Rights Movement. Indiana University Press. pp. 112–117. ISBN 0-253-20407-0.

- Stephanie R. Rolph, Resisting Equality: The Citizens' Council, 1954–1989 (2018) focuses on Mississippi.

- Klaus P. Fischer (2006). America in White, Black, and Gray: The Stormy 1960s. A&C Black. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-8264-1816-6.

- Robert Higgs, "Patterns of Farm Rental in the Georgia Cotton Belt, 1880–1900." Journal of Economic History 34.2 (1974): p. 468 Online.

- "Cotton Prices in the World Wars" Monthly Review (March 1944) pp 2-3.

- Arthur Raper, Preface to Peasantry (1936) pp 212-213.

- Raper, Preface to Peasantry (1936) pp 205-207, 278-79; quote on p 279.

- Mary Summers, "The New Deal farm programs: looking for reconstruction in American agriculture." Agricultural History 74.2 (2000): 241-257 online.

- Theodore Saloutos, "New Deal agricultural policy: an evaluation." Journal of American History 61.2 (1974): 394-416 online.

- Lee J. Alston; Joseph P. Ferrie (2007). "1: The Economics of Paternalism". Southern Paternalism and the American Welfare State: Economics, Politics, and Institutions in the South, 1865-1965. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-03579-8.

- James Noble Gregory (2005). The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8078-2983-7.

- D. W. Meinig (2010). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History. 4: Global America, 1915–2000. Yale University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-300-17394-9.

- Dale W. Wimberley, "Quality of Life Trends in the Southern Black Belt, 1980–2005: A Research Note*" Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25.1 (2010) updates the data into the 21st century. Online

- Derrick Shapley, Isolation in the South: Poverty and transportation infrastructure in the Black Belt (Mississippi State University, 2015).

- J. D. Pope, "Types of Farming Areas," in Agriculture of Alabama (Montgomery: 1930), pp. 53ff.

- Glenn N. Sisk, "Churches in the Alabama Black Belt 1875-1917" Church History 23#2 (1954), pp. 153-174 online

- Glenn N. Sisk, " Churches in the Alabama Black Belt 1875-1917" Church History 23#2 (1954), pp. 153-174 online

- Glenn N. Sisk, "Negro Churches in the Alabama Black Belt, 1875-1917" Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society (1955) 33#2: 87-92. Online

- Vernon Lane Wharton, The Negro in Mississippi: 1865-1890 (U of North Carolina Press, 1947), pp 256-65.

- Bradley Proctor, review of Michael W Fitzgerald, Reconstruction in Alabama in Journal of the Gilded Age & Progressive Era (2017, 15#4 pp. 542-544.

- Raybon, S. Paul (1992). "Stick by the old paths: an inquiry into the Southern Baptist response to Populism". American Baptist Quarterly. 11 (3): 241.

- Caner, Emir; Caner, Ergun (2003). The sacred trust: sketches of the Southern Baptist Convention presidents. Nashville, Tenn.: Broadman & Holman. p. 27. ISBN 080542668X. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- Casey Cater, "To Pick Up Again the Cross of Missionary Work: W. J. Northen's Politics of Race, Religion, and Reform, 1890-1911" Georgia Baptist History (2008), Vol. 21, pp 23-41

- Chrissy Lutz, and Dawn Herd-Clark, "'No One Was on Their Own': Sociability among Rural African American Women in Middle Georgia during the Interwar Years." Agricultural History 93.3 (2019): 437–451.

- Harold D. Woodman, "Economic Reconstruction and the Rise of the New South, 1865-1900" in John B. Boles, and Evelyn Thomas Nolen, Interpreting Southern history: Historiographical essays in honor of Sanford W. Higginbotham (LSU Press, 1987) pp. 273-274.

- Katherine Adams, "Du Bois, Dirt Determinism, and the Reconstruction of Global Value." American Literary History 31.4 (2019): 715-740.

- The Souls of Black Folk pp 93–94, 96, 100.

- The Souls of Black Folk pp 92, 106.

- Ashley A. Dumas, et al., "Cabins as Far as the Eyes Can See: An Introduction to the Black Belt Slave Housing Survey." Alabama Review 70.1 (2017) pp. 22-49.

Further reading

- Adams, Katherine. "Du Bois, Dirt Determinism, and the Reconstruction of Global Value." American Literary History 31.4 (2019): 715-740; explores the studies of black belt history by W.E.B. DuBois.

- Alston, Lee J., and Joseph P. Ferrie. "Social Control and Labor Relations in the American South Before the Mechanization of the Cotton Harvest in the 1950s" Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (1989): 133-157 Online.

- Brown, D. Clayton. King Cotton: A Cultural, Political, and Economic History since 1945 (University Press of Mississippi, 2011) 440 pp. ISBN 978-1-60473-798-1

- Fraser, Max, and RaMell Ross. "Filming the Black Belt: An Interview with RaMell Ross." Dissent 66.4 (2019): 30–37.

- Gibbs, Robert M. (2003). "Reconsidering the Southern Black Belt". The Review of Regional Studies. 33 (3): 254–263.

- Holloway, W. H. "A Black Belt County, Georgia," in W.E.B. DuBois, ed. The Negro Church (2003) pp 57-64.

- Johnson, Charles S. Statistical atlas of southern counties: listing and analysis of socio-economic indices of 1104 southern counties (1941). excerpt

- Kirby, Jack Temple. Rural Worlds Lost: The American South, 1920-1960 (LSU Press, 1986) major scholarly survey with detailed bibliography; online free to borrow.

- Lindsey, Lydia. "Black Lives Matter: Grace P. Campbell and Claudia Jones—An analysis of the Negro Question, Self-Determination, Black Belt Thesis." Journal of Pan African Studies 12.9 (2019): 110–144.

- McDonald, Robin, and Valerie Pope Burnes. Visions of the Black Belt: A Cultural Survey of the Heart of Alabama (University of Alabama Press, 2015).

- Odum, Howard W. Southern regions of the United States (U of North Carolina Press, 1936) online free.

- Raper, Arthur F. Preface to peasantry: A tale of two black belt counties (1936, reprinted Univ of South Carolina Press, 2005), a classic study of Black Belt life; Online free

- Roller, David C. and Robert W. Twyman, eds. The Encyclopedia of Southern History (Louisiana State University Press, 1979)

- Sisk, Glenn. "Post-War Vigor And Industry In The Alabama Black Belt." Mississippi Quarterly 12.2 (1959): 92-96. online

- Sisk, Glenn N. "Negro Education in the Alabama Black Belt, 1875-1900." Journal of Negro Education 22.2 (1953): 126-135.

- Sisk, Glenn S. "Crime and Justice in the Alabama Black Belt, 1875-1917." Mid-America 40 (1958): 106-113.

- Tullos, Allen. "The Black Belt." Southern Spaces (April 19, 2004) Online.

- Vance, Rupert B. Human factors in cotton culture; a study in the social geography of the American South (U of North Carolina Press, 1929) online free

- Webster, Gerald R., and Jerrod Bowman. "Quantitatively delineating the black belt geographic region." Southeastern Geographer 48.1 (2008): 3–18 Online.

- Wharton, Vernon Lane. The Negro in Mississippi: 1865-1890 (U of North Carolina Press, 1947).

- Wimberley, Dale W. "Quality of life trends in the Southern Black Belt, 1980-2005: a research note." Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25.1 (2010) Online.

- Wimberley, Ronald C. "It's Our Most Rural Region; It's the Poorest; It's the Black Belt South; and It Needs Our Attention." Journal of Rural Social Sciences 25.2 (2010): 175–182. online

- Wimberley, Ronald C. et al. "A Federal Commission for the Black Belt South" Professional Agricultural Workers Journal (PAWJ) 2#1: 6–9 online

- Wimberley, Ronald C.; Morris, Libby V. The Reference Book on Regional Well-Being: U.S. Regions, the Black Belt, Appalachia. (Southern Rural Development Center, Mississippi State University, 1996) online. Highly detailed Statistics from 1990 census.

- Winemiller, Terance L. "Black Belt Region in Alabama" Encyclopedia of Alabama (2009) online

- Yafa, Stephen. Big Cotton: How A Humble Fiber Created Fortunes, Wrecked Civilizations, and Put America on the Map (2004).