Ancient Chinese clothing

Ancient Chinese clothing or Hanfu refers to the historical clothing styles of China. The Han Chinese historically wore a robe or a shirt for the upper garment, while the lower garment was commonly a pleated skirt. Since the Han dynasty, Chinese clothing had developed varied styles and exquisite textile techniques, particularly on silk, and absorbed favorable elements in foreign cultures.[1] Ancient Chinese clothing was also influential to other traditional clothing such as the Japanese wafuku (kimono, yukata, etc),[2][3] Korean hanbok[4] and the Vietnamese Áo giao lĩnh.[5][6]

| Hanfu | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.png) "Hanfu" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉服 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢服 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Han Chinese's clothing" | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Garments

The style of historical Han clothing can be summarized as containing garment elements that are arranged in distinctive and sometimes specific ways. This is different from the traditional garment of other ethnic groups in China, most notably the Manchu-influenced clothes, the qipao, which is popularly considered to be the de facto traditional Han Chinese garb. A comparison of the two styles can be seen as the following provides:

| Component | Han | Manchu |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Garment | Consist of "yi" (衣), which have loose lapels and are open | Consist of "pao" (袍), which have secured lapels around the neck and no front openings |

| Lower Garment | Consist of skirts called "chang" (裳) | Consist of pants or trousers called "ku" (褲) |

| Collars | Generally, diagonally crossing each other, with the left crossing over the right | Parallel vertical collars with parallel diagonal lapels, which overlap |

| Sleeves | Long and loose | Narrow and tight |

| Buttons | Sparingly used and concealed inside the garment | Numerous and prominently displayed |

| Fittings | Belts and sashes are used to close, secure, and fit the garments around the waist | Flat ornate buttoning systems are typically used to secure the collar and fit the garment around the neck and upper torso |

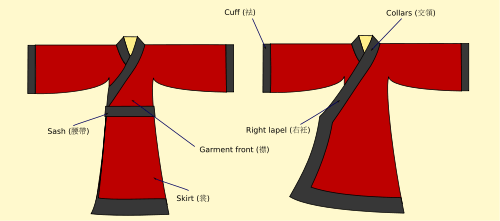

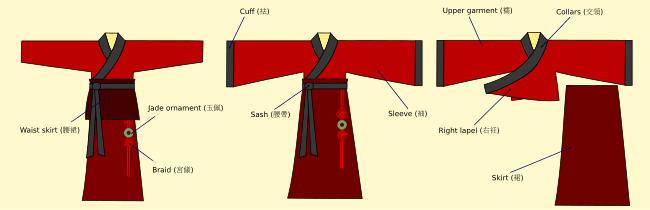

A complete set of garment is assembled from several pieces of clothing into an attire:

- Yi (衣): Any open cross-collar garment, and worn by both sexes

- Pao (袍): Any closed full-body garment, worn only by men

- Ru (襦): Open cross-collar shirt

- Shan (衫): Open cross-collar shirt or jacket that is worn over the yi

- Qun (裙) or chang (裳): Skirt for women and men

- Ku (褲): Trousers or pants

Hats, headwear and hairstyles

%2C_Chi-ning_City_(%E6%BF%9F%E5%AF%A7%E5%B8%82).jpg)

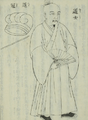

On top of the garments, hats (for men) or hairpieces (for women) may be worn. One can often tell the profession or social rank of someone by what they wear on their heads. The typical types of male headwear are called jin (巾) for soft caps, mao (帽) for stiff hats and guan (冠) for formal headdress. Officials and academics have a separate set of hats, typically the putou (幞頭), the wushamao (烏紗帽), the si-fang pingding jin (四方平定巾; or simply, fangjin: 方巾) and the Zhuangzi jin (莊子巾). A typical hairpiece for women is the ji (笄) but there are more elaborate hairpieces.

In addition, managing hair was also a crucial part of ancient Han people's daily life. Commonly, males and females would stop cutting their hair once they reached adulthood. This was marked by the Chinese coming of age ceremony Guan Li, usually performed between ages 15 to 20. They allowed their hair to grow long naturally until death, including facial hair. This was due to Confucius' teaching "身體髮膚,受諸父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也" – which can be roughly translated as 'My body, hair and skin are given by my father and mother, I dare not damage any of them, as this is the least I can do to honor and respect my parents'. In fact, cutting one's hair off in ancient China was considered a legal punishment called '髡', designed to humiliate criminals, as well as applying a character as a facial tattoo to notify one's criminality, the punishment is referred to as '黥', since regular people wouldn't have tattoos on their skin attributed to the same philosophy.

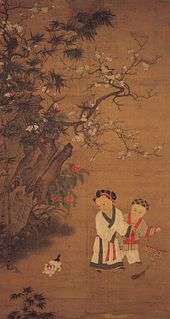

Children were exempt from the above commandment; they could cut their hair short, make different kinds of knots or braids, or simply just let them hang without any care, especially because such the decision was usually made by the parents rather than the children themselves, therefore, parental respect was not violated. However, once they entered adulthood, every male was obliged to tie his long hair into a bun called ji (髻) either on or behind his head and always cover the bun up with different kinds of headdresses (except Buddhist monks, who would always keep their heads completely shaved to show that they're "cut off from the earthly bonds of the mortal world"; and Taoist monks, who would usually just use hair sticks called '簪' (zān) to hold the buns in place without concealing them). Thus the 'disheveled hair', a common but erring depiction of ancient Chinese male figures seen in most modern Chinese period dramas or movies with hair (excluding facial hair) hanging down from both sides and/or in the back are historically inaccurate.[7] Females on the other hand, had more choices in terms of decorating their hair as adults. They could still arrange their hair into as various kinds of hairstyles as they pleased. There were different fashions for women in various dynastic periods.

Such strict "no-cutting" hair tradition was implemented all throughout Han Chinese history since Confucius' time up until the end of Ming dynasty (1644 CE), when the Qing Prince Dorgon forced the male Han people to adopt the hairstyle of Manchu men, which was shave their foreheads bald and gather the rest of the hair into ponytails in the back (See Queue) in order to show that they submitted to Qing authority, the so-called "Queue Order" (薙髮令). Han children and females were spared from this order, also Taoist monks were allowed to keep their hair and Buddhist monks were allowed to keep all their hair shaven. Han defectors to the Qing like Li Chengdong and Liu Liangzuo and their Han troops carried out the queue order to force it on the general population. Han Chinese soldiers in 1645 under Han General Hong Chengchou forced the queue on the people of Jiangnan while Han people were initially paid silver to wear the queue in Fuzhou when it was first implemented.[8]

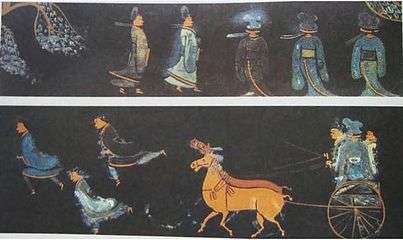

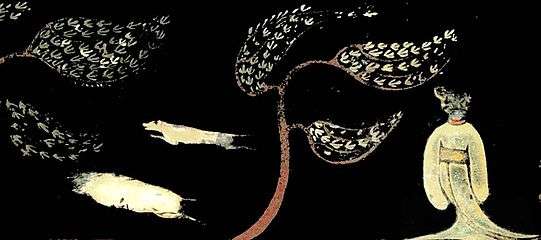

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīngmén chǔ mù) of the State of Chu (704–223 BC), depicting women and men wearing precursors to traditional silk dress) and riding in a two-horsed chariot

A lacquerware painting from the Jingmen Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīngmén chǔ mù) of the State of Chu (704–223 BC), depicting women and men wearing precursors to traditional silk dress) and riding in a two-horsed chariot

Fresco of a woman from a Western Han dynasty (206 B.C. – 8 A.D.) tomb in Xi'an

Fresco of a woman from a Western Han dynasty (206 B.C. – 8 A.D.) tomb in Xi'an Mural of two women with Han hairstyles, Dahuting Tomb

Mural of two women with Han hairstyles, Dahuting Tomb.jpg) Mural of a woman, Dahuting Tomb

Mural of a woman, Dahuting Tomb_from_Tomb_of_Lou_Jui_(%E5%A9%81%E5%8F%A1).jpg) A Northern Qi dynasty mural of a gate guard from the tomb of Lou Rui (婁叡).

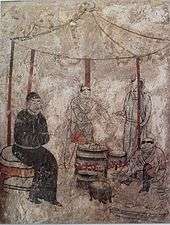

A Northern Qi dynasty mural of a gate guard from the tomb of Lou Rui (婁叡). A Song dynasty mural reflecting a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Dengfeng.

A Song dynasty mural reflecting a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Dengfeng.

| Man's Headwear | view | Woman's Headwear | view |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mianguan |  | Fengguan (鳳冠), lit. "phoenix crown". |  |

| Tongtianguan |  | Huasheng | |

| Pibian |  | Bian |  |

| Jinxianguan | Hairpin |  | |

| Longguan |  | ||

| Putou (襆頭), lit. "head cover" or "head wrap". An early form of informal headwear dates back as early as Jin dynasty that later developed into several variations for wear in different occasions. |  | ||

| Zhangokfutou (展角幞頭), lit. "spread-horn head cover", designed by the founder of Song dynasty, with elongated horns on both sides in order to keep the distance between his officials so they couldn't whisper to each other during court assemblies. It was also later adapted by the Ming dynasty, authorized for court wear. |  | ||

| Zhan Chi Fu Tou (展翅幞頭), lit. "spread-wing head cover", more commonly known by its nickname Wu Sha Mao (烏紗帽), lit. "black-cloth hat", was the standard headwear of officials during the Ming dynasty. The term "Wu Sha Mao" is still frequently used in modern Chinese slang when referring to a government position. |  | ||

| Yishanguan (翼善冠), lit. "winged crown of philanthropy", worn by emperors and princes of the Ming dynasty, as well as kings of many of its tributaries such as Korea and Ryukyu. The version worn by emperors was elaborately decorated with jewels and dragons, while the others looked like Wu Sha Mao but with wings folded upwards. |  | ||

| Pashou |  | ||

| Patou | |||

| Zhuzi jin |  | ||

| Zhouzi jin |  | ||

| Zhuangzi jin |  | ||

| Fujin |  | ||

| Li |  | ||

| Zi |  | ||

| Wangjing |  |

Style

Han Chinese clothing had changed and evolved with the fashion of the days since its commonly assumed beginnings in the Shang dynasty. Many of the earlier designs are more gender-neutral and simpler in cut than later examples. Later garments incorporate multiple pieces with men commonly wearing pants and women commonly wearing skirts. Clothing for women usually accentuates the body's natural curves through wrapping of upper garment lapels or binding with sashes at the waist.

Informal wear

Types include tops (yi) and bottoms (divided further into pants and skirts for both genders, with terminologies chang or qun), and one-piece robes that wrap around the body once or several times (shenyi).

- Zhongyi (中衣) or zhongdan (中單): inner garments, mostly white cotton or silk

- Shanqun (衫裙): a short coat with a long skirt

- Ruqun (襦裙): a top garment with a separate lower garment or skirt

- Kuzhe (褲褶): a short coat with trousers

- Zhiduo/zhishen (直裰/直身): a Ming dynasty style robe, similar to a zhiju shenyi but with vents at the side and 'stitched sleeves' (i.e. the sleeve cuff is closed save a small opening for the hand to go through)

- Daopao/Fusha (道袍/彿裟): Taoist/Buddhist priests' full dress ceremonial robes. Note: Daopao doesn't necessarily means Taoist's robe, it actually is a style of robe for scholars. The Taoist version of Daopao is called De Luo (得罗), and Buddhist version is called Hai Qing (海青).

A typical set of clothing can consist of two or three layers. The first layer of clothing is mostly the zhongyi (中衣) which is typically the inner garment much like a Western T-shirt and pants. The next layer is the main layer of clothing which is mostly closed at the front. There can be an optional third layer which is often an overcoat called a zhaoshan which is open at the front. More complicated sets can have many more layers.

For footwear, white socks and black cloth shoes (with white soles) are the norm, but in the past, shoes may have a front face panel attached to the tip of the shoes. Daoists, Buddhists and Confucians may have white stripe chevrons.

Semi-formal wear

A piece of ancient Chinese clothing can be "made semi-formal" by the addition of the following appropriate items:

- Chang (裳): a pleated skirt

- Bixi (蔽膝): long front cloth panel attached from the waist belt

- Zhaoshan (罩衫): long open fronted coat

- Guan (冠) or any formal hats

Generally, this form of wear is suitable for meeting guests or going to meetings and other special cultural days. This form of dress is often worn by the nobility or the upper-class as they are often expensive pieces of clothing, usually made of silks and damasks. The coat sleeves are often deeper than the shenyi to create a more voluminous appearance.

Formal wear

In addition to informal and semi-formal wear, there is a form of dress that is worn only at confucian rituals (like important sacrifices or religious activities) or by special people who are entitled to wear them (such as officials and emperors). Formal wear are usually long wear with long sleeves except Xuanduan.

Formal garments may include:

- Xuanduan (玄端): a very formal dark robe; equivalent to the Western white tie

- Shenyi (深衣): a long full body garment

- Quju (曲裾): diagonal body wrapping

- Zhiju (直裾): straight lapels

- Yuanlingshan (圓領衫), lanshan (襴衫) or panlingpao (盤領袍): closed, round-collared robe; mostly used for official or academical dress

| Style | Views | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuanduan |  |  |  |

|

| Shenyi | _por_Ku_K'ai-chih.jpg) |  | ||

|  |

|||

| Yuanlingshan |  |  |  |  |

The most formal dress civilians can wear is the xuanduan (sometimes called yuanduan 元端[9]), which consists of a black or dark blue top garment that runs to the knees with long sleeve (often with white piping), a bottom red chang, a red bixi (which can have a motif and/or be edged in black), an optional white belt with two white streamers hanging from the side or slightly to the front called peishou (佩綬), and a long black guan. Additionally, wearers may carry a long jade gui (圭) or wooden hu (笏) tablet (used when greeting royalty). This form of dress is mostly used in sacrificial ceremonies such as Ji Tian (祭天) and Ji Zu (祭祖), etc., but is also appropriate for state occasions. The xuanduan is basically a simplified version of full court dress of the officials and the nobility.

Those in the religious orders wear a plain middle layer garment followed by a highly decorated cloak or coat. Taoists have a 'scarlet gown' (絳袍)[10] which is made of a large cloak sewn at the hem to create very long deep sleeves used in very formal rituals. They are often scarlet or crimson in color with wide edging and embroidered with intricate symbols and motifs such as the eight trigrams and the yin and yang Taiji symbol. Buddhist have a cloak with gold lines on a scarlet background creating a brickwork pattern which is wrapped around over the left shoulder and secured at the right side of the body with cords. There may be further decorations, especially for high priests.[11]

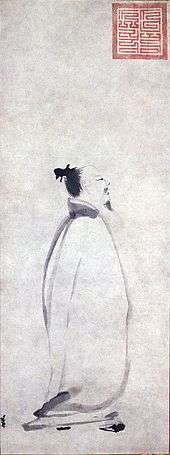

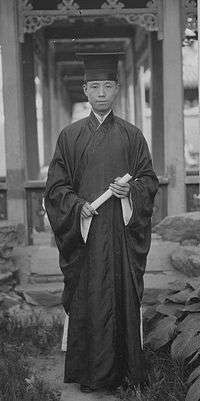

Those in academia or officialdom have distinctive gowns (known as changfu 常服 in court dress terms). This varies over the ages but they are typically round collared gowns closed at the front. The most distinct feature is the headwear which has 'wings' attached. Only those who passed the civil examinations are entitled to wear them, but a variation of it can be worn by ordinary scholars and laymen and even for a groom at a wedding (but with no hat).

Court dress

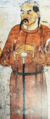

The Emperor's Mianfu (Sun Quan as Emperor, Three Kingdoms period)

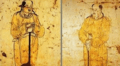

The Emperor's Mianfu (Sun Quan as Emperor, Three Kingdoms period) The Emperor in his court (Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou)

The Emperor in his court (Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou)- The Empress's Diyi (Empress Li Fengniang, Song dynasty)

- Diyi (Empress Wu, Song dynasty)

Princess of Cao Guo (曹國公主, personal name Zhu Fonv (朱佛女), sister of Hongwu Emperor, Ming dynasty)

Princess of Cao Guo (曹國公主, personal name Zhu Fonv (朱佛女), sister of Hongwu Emperor, Ming dynasty)

Seated portrait wearing Da Shan Xia Pei (大衫霞帔, lit. "The Grand Dress of Draping Radiance") Emperor's Yellow Pao (Yongle Emperor, Ming dynasty)

Emperor's Yellow Pao (Yongle Emperor, Ming dynasty) Gongfu (Emperor Zhenzong, Song dynasty)

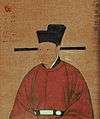

Gongfu (Emperor Zhenzong, Song dynasty)

Official's Changfu (Ming dynasty)

Official's Changfu (Ming dynasty) Lower rank official's Changfu (Ming dynasty)

Lower rank official's Changfu (Ming dynasty) Official dressed with different colored Changfu. (Ming dynasty)

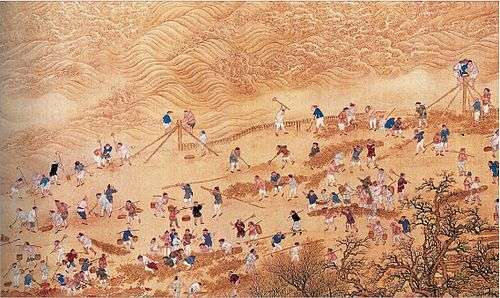

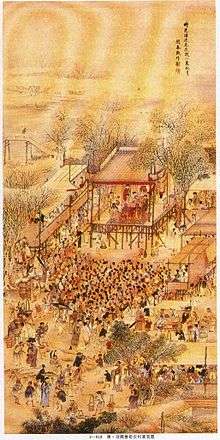

Official dressed with different colored Changfu. (Ming dynasty)- Court dress in a court assembly during the Wanli Era (Ming dynasty)

Court dress is the dress worn at very formal occasions and ceremonies that are in the presence of a monarch (such as an enthronement ceremony). The entire ensemble of clothing can consist of many complex layers and look very elaborate. Court dress is similar to the xuanduan in components but have additional adornments and elaborate headwear. They are often brightly colored with vermillion and blue. There are various versions of court dress that are worn for certain occasions.

Court dress refers to:

| Romanization | Hanzi | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Mianfu | 冕服 | religious court dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Bianfu | 弁服 | ceremonial military dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Chaofu | 朝服 | a red ceremonial court dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Gongfu | 公服 | formal court dress according to ranks |

| Changfu | 常服 | everyday court dress |

The practical use of court dress is now obsolete in the modern age since there is no reigning monarch in China anymore.

History

Traditional Han clothing comprises all traditional clothing classifications of the Han Chinese with a recorded history of more than three millennia until the end of the Ming Dynasty.[13] From the beginning of its history, Han clothing (especially in elite circles) was inseparable from silk, supposedly discovered by the Yellow Emperor's consort, Leizu. The Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC – 1000 BC), developed the rudiments of historical Chinese clothing; it consisted of a yi, a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash, and a narrow, ankle-length skirt, called chang, worn with a bixi, a length of fabric that reached the knees. Vivid primary colors and green were used, due to the degree of technology at the time.

The dynasty to follow the Shang, the Western Zhou dynasty, established a strict hierarchical society that used clothing as a status meridian, and inevitably, the height of one’s rank influenced the ornateness of a costume. Such markers included the length of a skirt, the wideness of a sleeve and the degree of ornamentation. In addition to these class-oriented developments, Han Chinese clothing became looser, with the introduction of wide sleeves and jade decorations hung from the sash which served to keep the yi closed. The yi was essentially wrapped over, in a style known as jiaoling youren, or wrapping the right side over before the left, because of the initially greater challenge to the right-handed wearer (people of Zhongyuan discouraged left-handedness like many other historical cultures, considering it unnatural, barbarian, uncivilized, and unfortunate).

Han Chinese clothing has influenced many of its neighbouring cultural costumes, such as the Japanese kimono and yukata,[2][3] and the Vietnamese Áo giao lĩnh.[5][6] Elements of Han Chinese clothing have also been influenced by neighbouring cultural costumes, especially by the nomadic peoples to the north, and Central Asian cultures to the west by way of the Silk Road.[14][15]

Tang dynasty

According to Chinaculture.org the Tang dynasty represents a golden age in China's history, where the arts, sciences and economy were thriving. Female dress and personal adornments in particular reflected the new visions of this era, which saw unprecedented trade and interaction with cultures and philosophies alien to Chinese borders. Although it still continues the clothing of its predecessors such as Han and Sui dynasties, fashion during the Tang was also influenced by its cosmopolitan culture and arts. Where previously Chinese women had been restricted by the old Confucian code to closely wrapped, concealing outfits, female dress in the Tang dynasty gradually became more relaxed, less constricting and even more revealing.[16] The Tang dynasty also saw the ready acceptance and syncretisation with Chinese practice, of elements of foreign culture by the Han Chinese. The foreign influences prevalent during Tang China included cultures from Gandhara, Turkistan, Persia and Greece. The stylistic influences of these cultures were fused into Tang-style clothing without any one particular culture having especial prominence.[17]

Emperor Gaozong of Tang ordered women to wear a type of clothing similar to the burnoose, covering the head and body with only a slit for vision. It was to stop women from being seen by men to enforce public decency. Women wore hoods that only let the face be shown or a veil that covered the sides of their head hanging from a broad rimmed hat, a curtain bonnet. But Gaozong was not even satisfied with these because they let the face be shown and he wanted the burnoose to return and cover the face.[18][19] The sil veil on the curtained hat was adopted from the Tuyuhun ethnic minority to the west and used to stop men from seeing women.[20][21] The Tang dynasty veils covered the women's face and neck.[22] Song dynasty women continued wearing this Tang dynasty women's veil which covered the head and upper body despite it's barbarian origin.[23] The full body veil originating from the Rong and Yi barbarians started to be worn by Chinese women of noble and aristicratic families during the Sui dynasty and was enforced with laws during the Tang dynasty to make women wear it sonce women started abandoning it for the weimao which only covered the head and face. It was to stop strangers from seeing women and viewed as proprietious.[24] The full body mili veil was for women riding on horses. The weimao was also called the humao (barbarian hat).[25] The veil worn by women in the Sui and Tang dynasties was of foreign origin from the western regions.[26] Noble women of the Tang dynasty wore the veil and after the Yonghui reign the veil with hat was worn.[27][28][29]

Song, Liao, Western Xia, Jin and Yuan dynasty

According to Chinaculture.org some features of Tang clothing carried into the Song dynasty such as court customs. Song court customs often use red color for their garments with black leather shoe and hats. Collar edges and sleeve edges of all clothes that have been excavated were decorated with laces or embroidered patterns. Such clothes were decorated with patterns of peony, camellia, plum blossom, and lily, etc. Song Empresses often had three to five distinctive jewelry-like marks on their face (two side of the cheek, other two next to the eyebrows and one on the forehead). Although some of Song clothing have similarities with previous dynasties, some unique characteristics separate it from the rest. Many of Song Clothing goes into Yuan and Ming.[30] One of the common clothing styles for woman during the Song dynasty was Beizi (褙子), which were usually regarded as shirt or jacket and could be matched with Ru or Ku. There are two size of Beizi: the short one is crown rump length and the long one extended to the knees.[31]

Unlike the tonsure of the Tangut Western Xia, the Jurchen hairstyle of wearing the queue combined with shaving the crown was not the invention of an emperor of the dynasty but was an established Jurchen hairstyle which showed who submitted to Jin rule. This Jurchen queue and shaving hairstyle was not enforced on the Han Chinese in the Jin after an initial attempt to do so which was a rebuke to Jurchen values.[32] The Jin at first attempted to impose Jurchen hairstyle and clothes on the Han population in the Jin but the order was taken back. They also banned intermarriage.[33]

Manchu Jurchen men had queues, while Mongol men swept their hair behind their ears and plaited them, Turk men wore loose hair and Xiongnu men braided their hair. Khitan males grew hair from their temples but shaved the crown of their heads. The Han Chinese men living in the Liao dynasty were not required to wear the shaved Khitan hairstyle which Khitan men wore to distinguish their ethnicity, unlike the Qing dynasty which mandated wearing of the Manchu hairstyle for men.[34] Khitan men left only two separate patches of hair on each of the forehead's sides in front of each ear in tresses while they shaved the top of their head. Khitan wore felt hats, fur clothes and woolen cloth and the Liao emperor switched between Han and Khitan clothing.[35] Khitan officials used gold ornamented ribbons to found their hair locks around their foreheads, covering their heads with felt hats according to the Ye Longli's (Yeh Lung-li) Qidan Guozhi (Ch'i-tan kuo-chih). Khitan wore the long side fringes & shaved pates.[36] Tomb murals of Khitan hairstyle show only some hair remaining near the neck and forehead with the rest of the head shaved.[37] Only at the temples were hair left while the crown was shaven.[38] The absence of Khitan clothes and hairstyles on a painting of riders previously identified as Khitan has lad to experts questioning their purported identity.[39] Khitan men might have differentiate between classes by wearing different patterns on their small braids hanging off their shaved foreheads. They wore the braids occasionally with a forehead fringe with some shaving off all the forehead.[40] Some Han men adopted and mixed or combined Han clothing with Khitan clothing with Khitan boots and Han clothes or wearing Khitan clothes. Han women on the other hand did not adopt Khitan dress and continued wearing Han dress.[41][42]

Non-Han women such as Central Asian women often adopted Han dress while their men didn't during the Tang dynasty. In the Liao dynasty, Khitan officials and the Liao empress wore Khitan clothes but the Han Chinese officials and Liao emperor wore Song clothes (Han clothes). The Liao had both Han style Tang and Song dynasty clothes and Khitan clothes. Both Khitan women and Han Chinese women in the Liao wore Han style Tang-Song dress.[43]

The Song dynasty banned people except for drama actors from wearing Jurchen and Khitan diaodun leggings. In the Yuan dynasty theater zaju drama actors wore all different clothes ranging from Jurchen, to Khitan, to Mongol, to Song Han Chinese clothes. The Ming dynasty had many Mongol clothes and cultural aspects abolished and enforced Tang dynasty style Han Chinese clothing.[44]

Horsemen

Horsemen Liao horsemen at rest

Liao horsemen at rest Liao hunters

Liao hunters

Khitan holding a mace

Khitan holding a mace Khitan guards

Khitan guards Khitans

Khitans Liao cooks

Liao cooks Khitan boys and girls

Khitan boys and girls_from_Tomb_in_Aohan%2C_Liao_Dynasty.jpg) Khitan hairstyle

Khitan hairstyle.jpg) Khitan women

Khitan women.jpg) Khitan women

Khitan women.jpg) Khotan woman

Khotan woman

Ming dynasty

Female's Ao Qun (襖裙, lit. coat-and-skirt), historical artifact kept in Kong Family Mansion.

Female's Ao Qun (襖裙, lit. coat-and-skirt), historical artifact kept in Kong Family Mansion. Commoner's clothing

Commoner's clothing Nicolas Trigault, a Flemish Jesuit in Ming style Confucian-scholar costume (Rufu 儒服).

Nicolas Trigault, a Flemish Jesuit in Ming style Confucian-scholar costume (Rufu 儒服).

Drawing by Peter Paul Rubens, 1617. A portrait painting of Nicolas Trigault believed to be wearing the same costume as shown in the drawing. By Rubens' workshop.

A portrait painting of Nicolas Trigault believed to be wearing the same costume as shown in the drawing. By Rubens' workshop.

According to the Veritable Records of Hongwu Emperor (太祖實錄, a detailed official account written by court historians recording the daily activities of Hongwu Emperor during his reign.), shortly after the founding of Ming dynasty, "on the Renzi day in the second month of the first year of Hongwu era (Feb 29th, 1368 CE), Hongwu emperor decreed that all fashions of clothing and headwear shall be restored to the standard of Tang, all citizens shall gather their hairs on top of their heads, and officials shall wear the Wu Sha Mao (black-cloth hats), round-collar robes, belts, and black boots." ("洪武元年二月壬子...至是,悉命復衣冠如唐制,士民皆束髮於頂,官則烏紗帽,圓領袍,束帶,黑靴。") This attempt to restore the entire clothing system back to the way it was during the Tang dynasty was a gesture from the founding emperor that signified the restoration of Han tradition and cultural identity after defeating the Yuan dynasty. However, fashionable Mongol attire, items and hats were still sometimes worn by early Ming royals such as Emperors Hongwu and Zhengde.[15][45]

According to Chinaculture.org the Ming dynasty also brought many changes to its clothing, as many dynasties do. They implemented metal buttons and the collar changed from the symmetrical type of the Song dynasty (960-1279) to the main circular type. Compared with the costume of the Tang dynasty (618-907), the proportion of the upper outer garment to lower skirt in the Ming dynasty was significantly inverted. Since the upper outer garment was shorter and the lower garment was longer, the jacket gradually became longer to shorten the length of the exposed skirt. Young ladies in the mid-Ming dynasty usually preferred to dress in these waistcoats. The waistcoats in the Qing dynasty were transformed from those of the Yuan dynasty. During the Ming dynasty, Confucian codes and ideals were popularized and it had a significant effect on clothing.[46]

When Han Chinese ruled the Vietnamese in the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam due to the Ming dynasty's conquest during the Ming–Hồ War they imposed the Han Chinese style of men wearing long hair on short haired Vietnamese men. Vietnamese were ordered to stop cutting and instead grow their hair long and switch to Han Chinese clothing in only a month by a Ming official. Ming administrators said their mission was to civilized the unorthodox Vietnamese barbarians.[47] The Ming dynasty only wanted the Vietnamese to wear long hair and to stop teeth blackening so they could have white teeth and long hair like Chinese.[48] A royal edict was issued by Vietnam in 1474 forbidding Vietnamese from adopting foreign languages, hairstyles and clothes like that of the Lao, Champa or the "Northerners" which referred to the Ming. The edict was recorded in the 1479 Complete Chronicle of Dai Viet of Ngô Sĩ Liên in the Later Lê dynasty.[49]

The Vietnamese had adopted the Chinese political system and culture during the 1,000 years of Chinese rule so they viewed their surrounding neighbors like Khmer Cambodians as barbarians and themselves as a small version of China (the Middle Kingdom).[50] By the Nguyen dynasty the Vietnamese themselves were ordering Cambodian Khmer to adopt Han Chinese culture by ceasing "barbarous" habits like cropping hair and ordering them to grow it long besides making them replace skirts with trousers.[51]

| A yapai (牙牌) from the Ming dynasty as mentioned in the painting above, this is the side engraved with instructions: the smaller text on the right reads "Officials who come to pay tribute [to the emperor] shall wear this card, those found without one will be prosecuted by law. Those who borrow or lend this card will be punished equally." The larger text on the left reads "Not required [to be checked] when outside the capital [Beijing]." |

| Official Dress Codes of the Ming Dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precedence | Rank | Robe Color | Animal on Patch (Civil) | Animal on Patch (Military) | Exemplified Positions (Not All-Inclusive) | ||

正一品 | Regional Commander 都督 | ||||||

從一品 | Regional Executive Officer 都督同知 | ||||||

正二品 | Secretary of Defense 兵部尚書 | ||||||

從二品 | Provincial Deputy Commander 都指揮同知 | ||||||

正三品 | Deputy Secretary of Labor 工部侍郎 | ||||||

從三品 | Minister of Salt Supply 都轉鹽運使 | ||||||

正四品 | Minister of Foreign Affairs 鴻臚寺卿 | ||||||

從四品 | Governor's Junior Assistant 參議 | ||||||

正五品 | Grand Secretary of the Cabinet 内閣大學士 | ||||||

從五品 | Deputy Manager of the Department of Justice 刑部員外郎 | ||||||

正六品 | Minister of Buddhist Affairs 僧錄司善世 | ||||||

從六品 | Deputy Manager of Minority Affairs 安撫司副使 | ||||||

正七品 | Investigating Censor 監察御史 | ||||||

從七品 | Deputy Ambassador 行人司左司副 | ||||||

正八品 | Deputy County Administrator 縣丞 | ||||||

從八品 | Supervisor at the Ministry of Royal Food Service 光祿寺監事 | ||||||

正九品 | (not seahorse) | Chief Officer at the Headquarter of Official Travels 會同館大使 | |||||

從九品 | Marshal 巡檢 | ||||||

Qing dynasty

A common misconception among Han Chinese was that Manchu clothing was entirely separate from Hanfu. In fact, Manchu clothes were simply modified Ming Hanfu but the Manchus promoted the misconception that their clothing was of different origin. Manchus originally did not have their own cloth or textiles and the Manchus had to obtain Ming dragon robes and cloth when they paid tribute to the Ming dynasty or traded with the Ming. These Ming robes were modified, cut and tailored to be narrow at the sleeves and waist with slits in the skirt to make it suitable for falconry, horse riding and archery. [52] The Ming robes were simply modified and changed by Manchus by cutting it at the sleeves and waist to make them narrow around the arms and waist instead of wide and added a new narrow cuff to the sleeves.[53] The new cuff was made out of fur. The robe's jacket waist had a new strip of scrap cloth put on the waist while the waist was made snug by pleating the top of the skirt on the robe.[54] The Manchus added sable fur skirts, cuffs and collars to Ming dragon robes and trimming sable fur all over them before wearing them.[55] Han Chinese court costume was modified by Manchus by adding a ceremonial big collar (da-ling) or shawl collar (pijian-ling).[56] It was mistakenly thought that the hunting ancestors of the Manchus skin clothes became Qing dynasty clothing, due to the contrast between Ming dynasty clothes unshaped cloth's straight length contrasting to the odd-shaped pieces of Qing dynasty long pao and chao fu. Scholars from the west wrongly thought they were purely Manchu. Chao fu robes from Ming dynasty tombs like the Wanli emperor's tomb were excavated and it was found that Qing chao fu was similar and derived from it. They had embroidered or woven dragons on them but are different from long pao dragon robes which are a separate clothing. Flaired skirt with right side fastenings and fitted bodices dragon robes have been found[57] in Beijing, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Jiangsu and Shandong tombs of Ming officials and Ming imperial family members. Integral upper sleeves of Ming chao fu had two pieces of cloth attached on Qing chao fu just like earlier Ming chao fu that had sleeve extensions with another piece of cloth attached to the bodice's integral upper sleeve. Another type of separate Qing clothing, the long pao resembles Yuan dynasty clothing like robes found in the Shandong tomb of Li Youan during the Yuan dynasty. The Qing dynasty chao fu appear in official formal portraits while Ming dynasty Chao fu that they derive from do not, perhaps indicating the Ming officials and imperial family wore chao fu under their formal robes since they appear in Ming tombs but not portraits. Qing long pao were similar unofficial clothing during the Qing dynasty.[58] The Yuan robes had hems flared and around the arms and torso they were tight. Qing unofficial clothes, long pao, derived from Yuan dynasty clothing while Qing official clothing, chao fu, derived from unofficial Ming dynasty clothing, dragon robes. The Ming consciously modeled their clothing after that of earlier Han Chinese dynasties like the Song dynasty, Tang dynasty and Han dynasty. In Japan's Nara city, the Todaiji temple's Shosoin repository has 30 short coats (hanpi) from Tang dynasty China. Ming dragon robes derive from these Tang dynasty hanpi in construction. The hanpi skirt and bodice are made of different cloth with different patterns on them and this is where the Qing chao fu originated.[59] Cross-over closures are present in both the hanpi and Ming garments. The eighth century Shosoin hanpi's variety show it was in vogue at the tine and most likely derived from much more ancient clothing. Han dynasty and Jin dynasty (266–420) era tombs in Yingban, to the Tianshan mountains south in Xinjiang have clothes resembling the Qing long pao and Tang dynasty hanpi. The evidence fron excavated tombs indicates that China had a long tradition of garments that led to the Qing chao fu and it was not invented or introduced by Manchus in the Qing dynasty or Mongols in the Yuan dynasty. The Ming robes that the Qing chao fu derived from were just not used in portraits and official paintings but were deemed as high status to be buried in tombs. In some cases the Qing went further than the Ming dynasty in imitating ancient China to display legitimacy with resurrecting ancient Chinese rituals to claim the Mandate of Heaven after studying Chinese classics. Qing sacrificial ritual vessels deliberately resemble ancient Chinese ones even more than Ming vessels.[60] Tungusic people on the Amur river like Udeghe, Ulchi and Nanai adopted Chinese influences in their religion and clothing with Chinese dragons on ceremonial robes, scroll and spiral bird and monster mask designs, Chinese New Year, using silk and cotton, iron cooking pots, and heated house from China during the Ming dynasty.[61]

The Spencer Museum of Art has six long pao robes that belonged to Han Chinese nobility of the Qing dynasty (Chinese nobility).[62] Ranked officials and Han Chinese nobles had two slits in the skirts while Manchu nobles and the Imperial family had 4 slits in skirts. All first, second and third rank officials as well as Han Chinese and Manchu nobles were entitled to wear 9 dragons by the Qing Illustrated Precedents. Qing sumptuary laws only allowed four clawed dragons for officials, Han Chinese nobles and Manchu nobles while the Qing Imperial family, emperor and princes up to the second degree and their female family members were entitled to wear five clawed dragons. However officials violated these laws all the time and wore 5 clawed dragons and the Spencer Museum's 6 long pao worn by Han Chinese nobles have 5 clawed dragons on them.[63]

When the Manchus established the Qing dynasty, the authorities issued decrees having Han Chinese men to adopt Manchu hairstyle by shaving their hair on the front of the head and braiding the hair on the back of the head into pigtails. The resistances against the hair shaving policy were suppressed.[65] Han Chinese did not object to wearing the queue braid on the back of the head as they traditionally wore all their hair long, but fiercely objected to shaving the forehead so the Qing government exclusively focused on forcing people to shave the forehead rather than wear the braid. Han rebels in the first half of the Qing who objected to Qing hairstyle wore the braid but defied orders to shave the front of the head. One person was executed for refusing to shave the front but he had willingly braided the back of his hair. It was only later westernized revolutionaries, influenced by western hairstyle who began to view the braid as backward and advocated adopting short haired western hairstyles.[66] Han rebels against the Qing like the Taiping even retained their queue braids on the back but the symbol of their rebellion against the Qing was the growing of hair on the front of the head, causing the Qing government to view shaving the front of the head as the primary sign of loyalty to the Qing rather than wearing the braid on the back which did not violate Han customs and which traditional Han did not object to.[67] Koxinga insulted and criticized the Qing hairstyle by referring to the shaven pate looking like a fly.[68] Koxinga and his men objected to shaving when the Qing demanded they shave in exchange for recognizing Koxinga as a feudatory.[69] The Qing demanded that Zheng Jing and his men on Taiwan shave in order to receive recognition as a fiefdom. His men and Ming prince Zhu Shugui fiercely objected to shaving.[70]

Some Han civilian men also voluntarily adopted Manchu clothing like Changshan on their own free will. By the late Qing, not only officials and scholars, but a great many commoners as well, started to wear Manchu attire.[71][72] As a result, Ming dynasty style clothing was even retained in some places in China during the Xinhai Revolution.[73]

During the Qing dynasty, Manchu style clothing was only required for scholar-official elite such as the Eight Banners members and Han men serving as government officials. For women's clothing, Manchu and Han fashions of clothing coexisted.[74] Throughout the Qing dynasty, Han women continued to wear clothing from Ming dynasty.[75] Neither Taoist priests nor Buddhist monks were required to wear the queue by the Qing; they continued to wear their traditional hairstyles, completely shaved heads for Buddhist monks, and long hair in the traditional Chinese topknot for Taoist priests.[76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85] To avoid wearing the queue and shaving the forehead, the Ming loyalist Fu Shan became a Daoist priest after the Qing took over Taiyuan.[86] In the Edo period of Tokugawa Shogunate Japan orders were passed for Japanese men to shave the pate on the front of their head (the chonmage hairstyle) and shave their beards, facial hair and side whiskers.[87] This was similar to the Qing dynasty queue order imposed by Dorgon making men shave the pates on the front of their heads.[88]

It was Han Chinese defectors who carried out massacres against people refusing to wear the queue. Li Chengdong, a Han Chinese general who had served the Ming but defected to the Qing,[89] ordered troops to carry out three separate massacres in the city of Jiading within a month, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. The third massacre left few survivors.[90] The three massacres at Jiading District are some of the most infamous, with estimated death tolls in the tens or even hundreds of thousands.[91] Jiangyin also held out against about 10,000 Qing troops for 83 days. When the city wall was finally breached on October 9, 1645, the Qing army, led by the Han Chinese Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐), who had been ordered to "fill the city with corpses before you sheathe your swords," massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.[92] Han Chinese soldiers in 1645 under Han General Hong Chengchou forced the queue on the people of Jiangnan while Han people were initially paid silver to wear the queue in Fuzhou when it was first implemented.[8][93]

Taoist priests continued to wear Taoist traditional dress and did not adopt Qing Manchu dress. After the Qing was toppled in the 1911 Xinhai revolution, the Taoist dress and topknot was adopted by the ordinary gentry and "Society for Restoring Ancient Ways" (Fuguhui) on the Sichuan and Hubei border where the White Lotus and Gelaohui operated.[94]

During the late Qing dynasty, the Vietnamese envoy to Qing China were still wearing the official attire in Ming dynasty style. Some of the locals recognised their clothing, yet the envoy received both amusement and ridicules from those who didn't.[95]

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (1)

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (1) Han female custom in Qing dynasty (2)

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (2) Children in Qing dynasty

Children in Qing dynasty Taoist Clothing in Qing dynasty

Taoist Clothing in Qing dynasty People in rain

People in rain

Hanfu movement in 21st century

The Hanfu movement is a fashion and social movement in the 21st century that seeks the revival of ancient Han Chinese clothing.[96] Some elements of the movement take inspiration from the use of indigenous clothing by ethnic minorities in China, as well as the usage of kimono in Japan and traditional clothing used in India.[97]

Traditional Ming dynasty Hanfu robes given by the Ming Emperors to the Chinese noble Dukes Yansheng descended from Confucius are still preserved in the Confucius Mansion after over five centuries. Robes from the Qing emperors are also preserved there.[98][99][100][101][102] The Jurchens in the Jin dynasty and Mongols in the Yuan dynasty continued to patronize and support the Confucian Duke Yansheng.[103]

Gallery

Detail of a lacquerware painting from the Ching-mên Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) of the State of Chu (704–223 BC)

Detail of a lacquerware painting from the Ching-mên Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) of the State of Chu (704–223 BC) A female servant and male advisor in Chinese silk robes, ceramic figurines from the Western Han period (202 BCE – 9 CE)

A female servant and male advisor in Chinese silk robes, ceramic figurines from the Western Han period (202 BCE – 9 CE) A Han dynasty fresco of a man in blue hunting dress

A Han dynasty fresco of a man in blue hunting dress%2C_Tung-p'ing_County_(%E6%9D%B1%E5%B9%B3%E7%B8%A3).jpg) A man dressing in the Han dynasty style Shên-i

A man dressing in the Han dynasty style Shên-i A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Museum, Chengdu

A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Museum, Chengdu

A mural painting showing a leisurely life scene 384-441 A.D., from the Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5 in Jiuquan, Later Liang - Northern Liang

A mural painting showing a leisurely life scene 384-441 A.D., from the Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5 in Jiuquan, Later Liang - Northern Liang_por_Ku_K'ai-chih_-_Duque_Yi_de_Wey.jpg)

Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706.

Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706. Buddhist donors of late Tang dynasty.

Buddhist donors of late Tang dynasty. A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms..jpg) Pao-shan tomb wall-painting of Liao dynasty.

Pao-shan tomb wall-painting of Liao dynasty. A Buddhist donor from early Northern Song dynasty.

A Buddhist donor from early Northern Song dynasty. A Song dynasty empress, wife of Emperor Zhenzong of Song

A Song dynasty empress, wife of Emperor Zhenzong of Song_by_Wang_Ch%C3%AAn-p'%C3%AAng.jpg) A female figure from Vimalakirti and the Doctrine of Nonduality, Yuan dynasty.

A female figure from Vimalakirti and the Doctrine of Nonduality, Yuan dynasty.

A Taoist priest in red colored gown

A Taoist priest in red colored gown A 1940s embroidered Han infant hat (繡帽; xiùmào) with double tigers, in the collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

A 1940s embroidered Han infant hat (繡帽; xiùmào) with double tigers, in the collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. An official at the Temple of Heaven, Beijing in 1913

An official at the Temple of Heaven, Beijing in 1913

A graduate of Yanjing University in 1930

A graduate of Yanjing University in 1930 Chinese hanfu worn during a festival in London

Chinese hanfu worn during a festival in London

See also

- Chinese academic dress

- Chinese clothing

- Cosplay

- Chinese culture

- Guan Li

- List of Hanfu

- Mandarin square

- Wafuku - a Japanese equivalent

- Hanbok - a Korean equivalent

References

- Yang, Shaorong (2004). Traditional Chinese Clothing: Costumes, Adornments & Culture. Long River Press. p. 3. ISBN 1592650198.

- Stevens, Rebecca (1996). The kimono inspiration: art and art-to-wear in America. Pomegranate. pp. 131–142. ISBN 978-0-87654-598-0.

- Dalby, Liza (2001). Kimono: Fashioning Culture. Washington, USA: University of Washington Press. pp. 25–32. ISBN 978-0-295-98155-0.

- JI, Yong; WANG, Ge-fei (November 2012). "Study on the relationship between Hanfu and Hanbok". Silk. 49 (11): 76–80. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- 《大南實錄・正編・第一紀・世祖實錄》,越南阮朝,國史館

- 《大南实录・正编・第一纪・卷五十四・嘉隆十五年七月条》,越南阮朝,國史館

- The Modern Hanfu - China Fashion Guide. Newhanfu.

- Michael R. Godley, "The End of the Queue:Hair as Symbol in Chinese History"

- Xu, Zhongguo Gudai Lisu Cidian, p. 7.

- "Daoist Headdresses and Dress – Scarlet Robe". taoism.org.hk. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06.

- "High Priest of the Shaolin Monastery". Newhanfu.

- Volpp, Sophie (June 2005). "The Gift of a Python Robe: The Circulation of Objects in "Jin Ping Mei"". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 65 (1): 133–158. doi:10.2307/25066765. JSTOR 25066765.

- Brown, John (2006). China, Japan, Korea: Culture and Customs. Createspace Independent Publishing (published September 7, 2006). p. 79. ISBN 978-1419648939.

- Finnane, Antonia (2008), Changing clothes in China: fashion, history, nation, Columbia University Press, pp. 44–46, ISBN 978-0-231-14350-9

- "Ancestors, The Story of China – BBC Two". BBC.

- Costume in the Tang Dynasty Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- Yoon, Ji-Won (2006). "Research of the Foreign Dancing Costumes: From Han to Sui-Tang Dynasty". 56. The Korean Society of Costume: 57–72. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Benn, Charles D. (2002). Daily Life in Traditional China: The Tang Dynasty. Greenwood Press "Daily life through history" series (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 0313309558. ISSN 1080-4749.

- Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty (illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0195176650.

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming (1987). 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Shang-hai shih hsi chʿü hsüeh hsiao. Chung-kuo fu chuang shih yen chiu tsu (reprint ed.). Commercial Press. p. 77. ISBN 9620750551.

- Li Shi. The History of Customs in Sui, Tang and Five Dynasties. Deep Into China Histories. DeepLogic.

- 臧, 迎春 (2003). 臧, 迎春 (ed.). 中国传统服饰. 臧迎春, 李竹润. 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 7508502795.

- Xu, Man (2016). Crossing the Gate: Everyday Lives of Women in Song Fujian (960-1279). SUNY Press. p. 72. ISBN 1438463227.

- Watt, James C. Y. (2004). China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD (illustrated ed.). Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 183. ISBN 1588391264.

- Hsu, Cho-yun (2012). China: A New Cultural History. Masters of Chinese Studies (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 220. ISBN 0231528183.

- 华, 梅 (2004). Chinese Clothing. Cultural China series. Hong Yu, 张蕾 (illustrated, reprint ed.). China Intercontinental Press. pp. 48, 55. ISBN 750850612X.

- 马, 承源; 岳, 峰, eds. (1998). 新疆维吾尔自治区絲路考古珎品, Volume 1. 上海博物館. 上海译文出版社. pp. 297, 298. Retrieved Nov 17, 2009.

- 郑, 重 (1991). Xie Zhiliu yi shu sheng ya. 中华书局(新)有限公司. p. 87.

- Behind the veil of the Forbidden City. Panda books. Yuehua Guan, Liangbi Zhong (illustrated ed.). Chinese Literature Press. 1996. pp. 43, 44, 146. ISBN 0835131785.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Costume in the Song Dynasty Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- ! e History of Chinese Ancient Clothing | Author:Chou XiBao 2011-01-01

- Keay, John (2011). China: A History (reprint ed.). Basic Books. p. 335. ISBN 0465025188.

- The Cambridge History of China: Alien regimes and border states, 907-1368. Volume 6 of The Cambridge History of China. Denis Crispin Twitchett, John King Fairbank. Cambridge University Press. 1994. p. 40.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Tackett, Nicolas (2017). The Origins of the Chinese Nation: Song China and the Forging of an East Asian World Order. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 1108186920.

- Zhu, Ruixi; Zhang, Bangwei; Liu, Fusheng; Cai, Chongbang; Wang, Zengyu (2016). A Social History of Medieval China. The Cambridge China Library. Bang Qian Zhu, Peter Ditmanson (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 34. ISBN 1107167868.

- Liu, Cary Yee-Wei; Ching, Dora C. Y., eds. (1999). Arts of the Sung and Yüan: Ritual, Ethnicity, and Style in Painting. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), Princeton University. Art Museum, Kuo li ku kung po wu yüan, Guo li gu gong bo wu yuan. Art Museum, Princeton University. pp. 168, 159, 179. ISBN 0943012309.

- Shen, Hsueh-man, ed. (2006). Gilded Splendor: Treasures of China's Liao Empire. Asia Society, Asia Society. Museum, Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (Berlin, Germany), Museum Rietberg (illustrated ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 114. ISBN 8874393326.

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming (1987). 5000 years of Chinese costumes. Shang-hai shih hsi chʿü hsüeh hsiao. Chung-kuo fu chuang shih yen chiu tsu (reprint ed.). Commercial Press. p. 130. ISBN 9620750551.

- Tung, W. U.; Tung, Wu (1997). Tales from the Land of Dragons: 1000 Years of Chinese Painting. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (illustrated ed.). Museum of Fine Arts. p. 136. ISBN 0878464395.

- Johnson, Linda Cooke (2011). Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China. UPCC book collections on Project MUSE (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 53, 190. ISBN 0824834046.

- Johnson, Linda Cooke (2011). Women of the Conquest Dynasties: Gender and Identity in Liao and Jin China. UPCC book collections on Project MUSE (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 48, 52, 53. ISBN 0824834046.

- China Review International, Volume 19. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Center for Chinese Studies. University of Hawaiʻi, Center for Chinese Studies and University of Hawaii Press. 2012. p. 101.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Shea, Eiren L. (2020). Mongol Court Dress, Identity Formation, and Global Exchange. Routledge Research in Art History (illustrated ed.). Routledge. ISBN 1000027899.

- Wang, Guojun (2020). Staging Personhood: Costuming in Early Qing Drama. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231549571.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-05-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Costume in the Ming Dynasty Archived 2008-12-05 at the Wayback Machine chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- The Vietnam Review: VR., Volume 3. Vietnam Review. 1997. p. 35.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 110. ISBN 1316531317.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Introduction to Asian Civilizations (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0231511108.

- Chanda, Nayan (1986). Brother Enemy: The War After the War (illustrated ed.). Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 53, 111.

- Chandler, David (2018). A History of Cambodia (4 ed.). Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 0429964064.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 157. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 158. ISBN 0520300297.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 159. ISBN 0520300297.

- Schlesinger, Jonathan (2017). A World Trimmed with Fur: Wild Things, Pristine Places, and the Natural Fringes of Qing Rule. Stanford University Press. p. 25. ISBN 1503600688.

- Chung, Young Yang Chung (2005). Silken threads: a history of embroidery in China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam (illustrated ed.). Harry N. Abrams. p. 148. Retrieved Dec 4, 2009.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 103. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 104. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 105. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 106. ISBN 1555952380.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581-1990 (illustrated, reprint, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521477719.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 115. ISBN 1555952380.

- Dusenbury, Mary M.; Bier, Carol. Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (ed.). Flowers, Dragons & Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art (illustrated ed.). Hudson Hills. p. 117. ISBN 1555952380.

- Keliher, Macabe (2019). The Board of Rites and the Making of Qing China. Univ of California Press. p. 149. ISBN 0520300297.

- 呤唎 (February 1985). 《太平天國革命親歷記》. 上海古籍出版社.

- Godley, Michael R. (September 2011). "The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History". China Heritage Quarterly. China Heritage Project, ANU College of Asia & the Pacific (CAP), The Australian National University (27). ISSN 1833-8461.

- Meyer-Fong, Tobie (2013). What Remains: Coming to Terms with Civil War in 19th Century China (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0804785597.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 1316453847.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 86. ISBN 1316453847.

- Hang, Xing (2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 1316453847.

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K. (2008) Cambridge History of China Volume 9 Part 1 The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, p87-88

- 千志, 魏 (1998). 《明清史概論》. 中國社會科學出版社. pp. 358–360.

- Shaorong Yang (2004). Traditional Chinese Clothing Costumes, Adornments & Culture. Long River Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-59265-019-4.

Men's clothing in the Qing Dyansty consisted for the most part of long silk growns and the so-called "Mandarin" jacket, which perhaps achieved their greatest popularity during the latter Kangxi Period to the Yongzheng Period. For women's clothing, Manchu and Han systems of clothing coexisted.

- 周, 锡保 (2002-01-01). 《中国古代服饰史》. 中国戏剧出版社. p. 449. ISBN 9787104003595..

- Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- Gerolamo Emilio Gerini (1895). Chŭlăkantamangala: Or, The Tonsure Ceremony as Performed in Siam. Bangkok Times. pp. 11–.

- The Museum Journal. The Museum. 1921. pp. 102–.

- George Cockburn (1896). John Chinaman: His Ways and Notions. J. Gardner Hitt. pp. 86–.

- Robert van Gulik (15 November 2010). Poets and Murder: A Judge Dee Mystery. University of Chicago Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-226-84896-9.

- James William Buel (1883). Mysteries and Miseries of America's Great Cities: Embracing New York, Washington City, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans. A.L. Bancroft & Company. pp. 312–.

- Justus Doolittle (1876). Social Life of the Chinese: With Some Account of Their Religious, Governmental, Educational, and Business Customs and Opinions. With Special But Not Exclusive Reference to Fuhchau. Harpers. pp. 241–.

- Justus Doolittle, Social life of the Chinese : with some account of their religious, governmental, educational and business customs and opinions, with special but not exclusive reference to Fuhchau c

- East Asian History. Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University. 1994. p. 63.

- Michael R. Godley, The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History

- Bai, Qianshen (2003). Fu Shan's World: The Transformation of Chinese Calligraphy in the Seventeenth Century. 220 of Harvard East Asian monographs (illustrated ed.). Harvard University Asia Center. p. 85. ISBN 0674010922. ISSN 0073-0483.

- Toby, Ron P. (2019). Engaging the Other: 'Japan' and Its Alter-Egos, 1550-1850. Brill's Japanese Studies Library. BRILL. p. 217. ISBN 900439351X.

- Toby, Ron P. (2019). Engaging the Other: 'Japan' and Its Alter-Egos, 1550-1850. Brill's Japanese Studies Library. BRILL. p. 214. ISBN 900439351X.

- Faure (2007), p. 164.

- Ebrey (1993)

- Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. Simon and Schuster. p. 271.

- Wakeman 1975b, p. 83.

- Justus Doolittle (1876). Social Life of the Chinese: With Some Account of Their Religious, Governmental, Educational, and Business Customs and Opinions. With Special But Not Exclusive Reference to Fuhchau. Harpers. pp. 242–.

- Hair: Its Power and Meaning in Asian Cultures (illustrated ed.). SUNY Press. 1998. p. 137. ISBN 0791437418.

- Trần Quang Đức (2013). Ngàn năm áo mũ (PDF). Nhã Nam. p. 31. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

清朝承平日久…唯衣服之製度不改,滿俗終乏雅觀…自清朝入帝中國,四方薙髮變服,二百年來,人已慣耳目[…]不曾又識初來華夏樣矣。我國使部來京,穿戴品服,識者亦有竊羨華風,然其不智者,多群然笑異,見襆頭網巾衣帶,便皆指為倡優樣格,胡俗之移人,一至浩歎如此

- Ying, Zhi (2017). The Hanfu Movement and Intangible Cultural Heritage: considering The Past to Know the Future (MSc). University of Macau/Self-published. p. 12.

- 华, 梅 (14 June 2007). "汉服堪当中国人的国服吗?". People's Daily Online.

- Zhao, Ruixue (2013-06-14). "Dressed like nobility". China Daily.

- "Confucius family's secret legacy comes to light". Xinhua. 2018-11-28.

- Sankar, Siva (2017-09-28). "A school that can teach the world a lesson". China Daily.

- Wang, Guojun (December 2016). "The Inconvenient Imperial Visit: Writing Clothing and Ethnicity in 1684 Qufu". Late Imperial China. Johns Hopkins University Press. 37 (2): 137–170. doi:10.1353/late.2016.0013.

- Kile, S.E.; Kleutghen, Kristina (June 2017). "Seeing through Pictures and Poetry: A History of Lenses (1681)". Late Imperial China. Johns Hopkins University Press. 38 (1): 47–112. doi:10.1353/late.2017.0001.

- Sloane, Jesse D. (October 2014). "Rebuilding Confucian Ideology: Ethnicity and Biography in the Appropriation of Tradition". Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. 14 (2): 235–255. ISSN 1598-2661.

Bibliography

- Zhou, Xibao (1984). 【中國古代服飾史】 [History of Ancient Chinese Costume]. Beijing: Zhongguo Xiju.

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming; The Chinese Costumes Research Group (1984), 5000 Years of Chinese Costume, Hong Kong: The Commercial Press. ISBN 962-07-5021-7

- Xu, Jialu (許嘉璐) (1991). 【中國古代禮俗辭典】 [Dictionary of Rituals and Customs of Ancient China].

- Shen, Congwen (2006). 【中國古代服飾研究】 [Researches on Ancient Chinese Costumes]. Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Group. ISBN 978-7-80678-329-0.

- Huang, Nengfu (黃能馥); Chen, Juanjuan (陳娟娟) (1999). 【中華歷代服飾藝術】 [The Art of Chinese Clothing Through the Ages]. Beijing.

- Hua, Mei (華梅) (2004). 【古代服飾】 [Ancient Costume]. Beijing: Wenmu Chubanshe. ISBN 978-7-5010-1472-9.

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming (1988). 5000 years of Chinese costumes. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 978-0-8351-1822-4.

External links