History of clothing and textiles

The study of the history of clothing and textiles traces the development, use, and availability of clothing and textiles over human history. Clothing and textiles reflect the materials and technologies available in different civilizations at different times. The variety and distribution of clothing and textiles within a society reveal social customs and culture.

The wearing of clothing is exclusively a human characteristic and is a feature of most human societies. Men and women began wearing clothes after the last Ice Age. Anthropologists believe that animal skins and vegetation were adapted into coverings as protection from cold, heat and rain, especially as humans migrated to new climates.

Textiles can be felt or spun fibers made into yarn and subsequently netted, looped, knit or woven to make fabrics, which appeared in the Middle East during the late Stone Age.[1] From the ancient times to the present day, methods of textile production have continually evolved, and the choices of textiles available have influenced how people carried their possessions, clothed themselves, and decorated their surroundings.[2]

Sources available for the study of clothing and textiles include material remains discovered via archaeology; representation of textiles and their manufacture in art; and documents concerning the manufacture, acquisition, use, and trade of fabrics, tools, and finished garments. Scholarship of textile history, especially its earlier stages, is part of material culture studies.

Prehistoric development

The development of textile and clothing manufacture in prehistory has been the subject of a number of scholarly studies since the late 20th century.[3][4] These sources have helped to provide a coherent history of these prehistoric developments. Evidence suggests that humans may have begun wearing clothing as far back as 100,000 to 500,000 years ago.[5]

Early adoption of apparel

Genetic analysis suggests that the human body louse, which lives in clothing, may only have diverged from the head louse some 170,000 years ago, which supports evidence that humans began wearing clothing at around this time. These estimates predate the first known human exodus from Africa, although other hominid species who may have worn clothes – and shared these louse infestations – appear to have migrated earlier.

Sewing needles have been dated to at least 50,000 years ago (Denisova Cave, Siberia) – and uniquely associated with a human species other than modern humans, i.e. H. Denisova/H. Altai. The oldest possible example is 60,000 years ago, a needlepoint (missing stem and eye) found in Sibudu Cave, South Africa. Other early examples of needles dating from 41,000-15,000 years ago are found in multiple locations, e.g. Slovenia, Russia, China, Spain, and France.

The earliest dyed flax fibres have been found in a prehistoric cave in Georgia and date back to 36,000.[6]

The 25,000-year-old Venus Figurine "Venus of Lespugue", found in southern France in the Pyrenees, depicts a cloth or twisted fiber skirt. Other figurines from western Europe were adorned with basket hats or caps, belts were worn at the waist, and a strap of cloth that wrapped around the body right above the breast. Eastern European figurines wore belts, hung low on the hips and sometimes string skirts.

Archaeologists have discovered artifacts from the same period that appear to have been used in the textile arts: (5000 BC) net gauges, spindle needles, and weaving sticks.

Ancient textiles and clothing

The first actual textile, as opposed to skins sewn together, was probably felt. Surviving examples of Nålebinding, another early textile method, date from 6500 BC. Knowledge of ancient textiles and clothing has expanded in the recent past due to modern technological developments.[7] Our knowledge of cultures varies greatly with the climatic conditions to which archeological deposits are exposed; the Middle East and the arid fringes of China have provided many very early samples in good condition, but the early development of textiles in the Indian subcontinent, sub-Saharan Africa and other moist parts of the world remains unclear. In northern Eurasia, peat bogs can also preserve textiles very well. The first known textile of South America was discovered in Guitarrero Cave in Peru. It was woven out of vegetable fibers and dates back to 8,000 B.C.E.

From pre-history through the early Middle Ages, for most of Europe, the Near East and North Africa, two main types of loom dominate textile production. These are the warp-weighted loom and the two-beam loom. The length of the cloth beam determined the width of the cloth woven upon it, and could be as wide as 2–3 meters. The second loom type is the two-beam loom.[8] Early woven clothing was often made of full loom widths draped, tied, or pinned in place.

The textile trade in the ancient world

Throughout the Neolithic and Bronze Ages, the fertile grounds of the Eurasian Steppe provided a venue for a network of nomadic communities to develop and interact. The Steppe Route has always connected regions of the Asian continent with trade and transmission of culture, including clothing.

Around 114 BC, the Han Dynasty,[9] initiated the Silk Road Trade Route. Geographically, the Silk Road or Silk Route is an interconnected series of ancient trade routes between Chang'an (today's Xi'an) in China, with Asia Minor and the Mediterranean extending over 8,000 km (5,000 mi) on land and sea. Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of the great civilizations of China, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, the Indian subcontinent, and Rome, and helped to lay the foundations for the modern world. The exchange of luxury textiles was predominant on the Silk Road, which linked traders, merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads and urban dwellers from China to the Mediterranean Sea during various periods of time.

Ancient Near East

The earliest known woven textiles of the Near East may be fabrics used to wrap the dead, excavated at a Neolithic site at Çatalhöyük in Anatolia, carbonized in a fire and radiocarbon dated to c. 6000 BC.[10] Evidence exists of flax cultivation from c. 8000 BC in the Near East, but the breeding of sheep with a wooly fleece rather than hair occurs much later, c. 3000 BC.[10]

In Mesopotamia, the clothing of a regular Sumerian was very simple, especially in summer, in the winter wearing clothes made of sheep fur. Even wealthy men were depicted with naked torsos, wearing just some kind of short skirt, known as kaunakes, while women wore long dress to their ankles. The king wore a tunic, a coat that reached to his knees, with a belt in the middle. Over time, the development of the craft of wool weaving has led to a great variety in clothing. Thus, towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC and later the men wore a tunic with short sleeves and even over the knees, with a belt (over which the rich wore a wool cloak). Women's dresses featured more varied designs: with or without sleeves, narrow or wide, usually long and without highlighting the body[11]

A possible bone belt hook found in the Bronze Age layers of Yanik Tepe, from northeast of Lake Urmia (Iran)

A possible bone belt hook found in the Bronze Age layers of Yanik Tepe, from northeast of Lake Urmia (Iran) Sumerian Statues of worshippers (males and females); 2800-2400 BC (Early Dynastic period); National Museum of Iraq (Baghdad)

Sumerian Statues of worshippers (males and females); 2800-2400 BC (Early Dynastic period); National Museum of Iraq (Baghdad)

The Statue of Ebih-Il; c. 2400 BCE; gypsum, schist, shells and lapis lazuli; height: 52.5 cm; Louvre (Paris)

The Statue of Ebih-Il; c. 2400 BCE; gypsum, schist, shells and lapis lazuli; height: 52.5 cm; Louvre (Paris)

Ancient India

We do not know what the people who constituted the Indus Valley Civilization, one of the earliest civilizations of the world, actually wore. Any cloth that might have been worn has long since disintegrated and we have not yet been able to decipher the Indus script. However, historians and archaeologists have managed to piece together some bits of information from clues found in sculptures and figurines.

Terracotta figurines uncovered at Mehrgarh show a male figure wearing what is commonly interpreted to be a turban; female figurines depict women with elaborate headdress and intricate hairstyles.[13] In certain cases, these headdresses have led historians to attach a religious connotation to the figurines and to the interpret the headdresses as symbols of a mother goddess.

One of the most important recovered figurines is that of the "Priest King" from the site of Mohenjo-daro. It is not only important because scholars have called it a representation of an assumed authority or head of state but also because of what it is wearing, however, it was recently discovered to be an interpretation of a wealthy trader. The calmly seated Priest-King is depicted wearing a shawl with floral patterns. So far, this is the only sculpture from the Indus Valley to show clothing in such explicit detail. However, it does not provide any concrete proof to legitimize the history of clothing in the Harappan times. Harappans may even have used natural colours to dye their fabric. Research shows that the cultivation of indigo plants (genus: Indigofera) was prevalent.

Another important sculpture is of a dancing girl, also excavated from Mohenjo-daro. She is depicted with no clothing other than a number of bangles upon her arm. B. B. Lal[14] has managed draw parallels between the dancing girl and women today in parts of Rajasthan and Gujarat. He notices how contemporary women continue wearing those bangles even today. Harappans may not have left any evidence of what clothing or textiles they had at that time but they did leave remains of jewellery and beads in large amounts. For instance, the graves of Harappans have yielded various forms of jewellery such as neckpieces, bracelets, rings, and head ornaments. Multiple beads of varying shapes and sizes have also been recovered. This jewellery incorporates various materials such as gold, bronze, terracotta, faience, and shells; imported materials including turquoise and lapis lazuli were used too. This suggests that the Harappans might have engaged in long-distance trade. Long, slender carnelian beads were highly prized by the Harappans. Harappans were also experts in manufacturing microbeads, which have been found in various locations from hearths and graves. These beads were extremely hard to work with and needed extra precision to produce. A special drill has been found both at Lothal and Chanhudaro. Chanhudaro was a centre exclusively devoted to craft production.

Statue of "Priest King" wearing a robe; 2400–1900 BCE; low fired steatite; National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi)

Statue of "Priest King" wearing a robe; 2400–1900 BCE; low fired steatite; National Museum of Pakistan (Karachi) The Didarganj Yakshi depicting the dhoti wrap; circa 300 BC; Bihar Museum (India)

The Didarganj Yakshi depicting the dhoti wrap; circa 300 BC; Bihar Museum (India).jpeg)

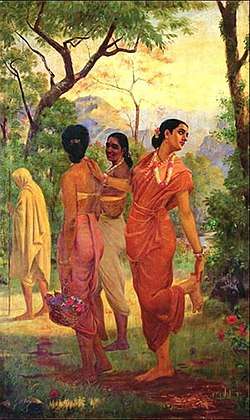

Shakuntala, wife of Dushyanta and the mother of Emperor Bharata, from Kalidasa's play Abhijñānaśākuntala, wearing a sari, painting by Raja Ravi Varma

Shakuntala, wife of Dushyanta and the mother of Emperor Bharata, from Kalidasa's play Abhijñānaśākuntala, wearing a sari, painting by Raja Ravi Varma Painting on wooden panel discovered by Aurel Stein in Dandan Oilik, depicting the legend of the princess who hid silk worm eggs in her headdress to smuggle them out of China to the Kingdom of Khotan; 7th to 8th century; British Museum (London)

Painting on wooden panel discovered by Aurel Stein in Dandan Oilik, depicting the legend of the princess who hid silk worm eggs in her headdress to smuggle them out of China to the Kingdom of Khotan; 7th to 8th century; British Museum (London)

Ancient Egypt

Evidence exists for production of linen cloth in Ancient Egypt in the Neolithic period, c. 5500 BC. Cultivation of domesticated wild flax, probably an import from the Levant, is documented as early as c. 6000 BC. Other bast fibers including rush, reed, palm, and papyrus were used alone or with linen to make rope and other textiles. Evidence for wool production in Egypt is scanty at this period.[15]

Spinning techniques included the drop spindle, hand-to-hand spinning, and rolling on the thigh; yarn was also spliced.[15] A horizontal ground loom was used prior to the New Kingdom, when a vertical two-beam loom was introduced, probably from Asia.

Linen bandages were used in the burial custom of mummification, and art depicts Egyptian men wearing linen kilts and women in narrow dresses with various forms of shirts and jackets, often of sheer pleated fabric.[15]

_(14741944536).jpg) Illustration from the book Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations

Illustration from the book Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations_(14761789471).jpg) Illustration of a Goddess from Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations

Illustration of a Goddess from Ancient Egyptian, Assyrian, and Persian costumes and decorations- Statue of Sobekhotep VI, who wears the Egyptian male skirt, the shendyt, from Neues Museum (Berlin, Germany)

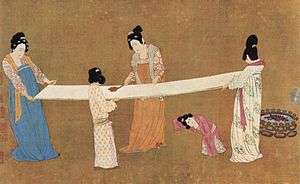

Ancient China

The earliest evidence of silk production in China was found at the sites of Yangshao culture in Xia, Shanxi, where a cocoon of bombyx mori, the domesticated silkworm, cut in half by a sharp knife is dated to between 5000 and 3000 BC. Fragments of primitive looms are also seen from the sites of Hemudu culture in Yuyao, Zhejiang, dated to about 4000 BC. Scraps of silk were found in a Liangzhu culture site at Qianshanyang in Huzhou, Zhejiang, dating back to 2700 BC.[16][17] Other fragments have been recovered from royal tombs in the [Shang Dynasty] (c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC).[18]

Under the Shang Dynasty, Han Chinese clothing or Hanfu consisted of a yi, a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash, and a narrow, ankle-length skirt, called shang, worn with a bixi, a length of fabric that reached the knees. Clothing of the elite was made of silk in vivid primary colours.

Painting of Emperor Yao wearing a shenyi

Painting of Emperor Yao wearing a shenyi The Yellow Emperor wearing a mianguan

The Yellow Emperor wearing a mianguan

The mianfu of Emperor Wu of Jin dynasty, 7th-century painting by court artist Yan Liben

The mianfu of Emperor Wu of Jin dynasty, 7th-century painting by court artist Yan Liben

Ancient Thailand

The earliest evidence of spinning in Thailand can be found at the archaeological site of Tha Kae located in Central Thailand. Tha Kae was inhabited during the end of the first millennium BC to the late first millennium AD. Here, archaeologists discovered 90 fragments of a spindle whorl dated from 3rd century BC to 3rd century AD. And the shape of these finds indicate the connections with south China and India.[19]

Ancient Japan

The earliest evidence of weaving in Japan is associated with the Jōmon period. This culture is defined by pottery decorated with cord patterns. In a shell mound in the Miyagi Prefecture, dating back about 5,500, some cloth fragments were discovered made from bark fibers.[20] Hemp fibers were also discovered in the Torihama shell mound, Fukui Prefecture, dating back to the Jōmon period, suggesting that these plants could also have been used for clothing. Some pottery pattern imprints depict also fine mat designs, proving their weaving techniques. The patterns on the Jōmon pottery show people wearing short upper garments, close-fitting trousers, funnel-sleeves, and rope-like belts. The depictions also show clothing with patterns that are embroidered or painted arched designs, though it is not apparent whether this indicates what the clothes look like or whether that simply happens to be the style of representation used. The pottery also shows no distinction between male and female garments. This may have been true because during that time period clothing was more for decoration than social distinction, but it might also just be because of the representation on the pottery rather than how people actually dressed at the time. Since bone needles were also found, it is assumed that they wore dresses that were sewn together.[21]

Next was the Yayoi period, during which rice cultivation was developed. This led to a shift from hunter-gatherer communities to agrarian societies which had a large impact on clothing. According to Chinese literature from that time period, clothing more appropriate to agriculture began to be worn. For example, an unsewn length of fabric wrapped around the body, or a poncho-type garment with a head-hole cut into it. This same literature also indicates that pink or scarlet makeup was worn but also that mannerisms between people of all ages and genders were not very different. However, this is debatable as there were probably cultural prejudices in the Chinese document. There is a common Japanese belief that the Yayoi time period was quite utopian before Chinese influence began to promote the use of clothing to indicate age and gender.

From 300 to 550 AD was the Yamato period, and here much of the clothing style can be derived from the artifacts of the time. The tomb statues (haniwa) especially tell us that the clothing style changed from the ones according to the Chinese accounts from the previous age. The statues are usually wearing a two piece outfit that has an upper piece with a front opening and close-cut sleeves with loose trousers for men and a pleated skirt for women. Silk farming had been introduced by the Chinese by this time period but due to silk's cost it would only be used by people of certain classes or ranks.

The following periods were the Asuka (550 to 646 AD) and Nara (646 to 794 AD) when Japan developed a more unified government and began to use Chinese laws and social rankings. These new laws required people to wear different styles and colors to indicate social status. Clothing became longer and wider in general and sewing methods were more advanced.[22]

Classical Period of the Philippines

The classical Filipino clothing varied according to cost and current fashions and so indicated social standing. The basic garments were the Bahag and the tube skirt—what the Maranao call malong—or a light blanket wrapped around instead. But more prestigious clothes, lihin-lihin, were added for public appearances and especially on formal occasions—blouses and tunics, loose smocks with sleeves, capes, or ankle-length robes. The textiles of which they were made were similarly varied. In ascending order of value, they were abaca, abaca decorated with colored cotton thread, cotton, cotton decorated with silk thread, silk, imported printstuff, and an elegant abaca woven of selected fibers almost as thin as silk. In addition, Pigafetta mentioned both G-strings and skirts of bark cloth.

Untailored clothes, however had no particular names. Pandong, a lady's cloak, simply meant any natural covering, like the growth on banana trunk's or a natal caul. In Panay, the word kurong, meaning curly hair, was applied to any short skirt or blouse; and some better ones made of imported chintz or calico were simply called by the name of the cloth itself, tabas. So, too, the wraparound skirt the Tagalogs called tapis was hardly considered a skirt at all: Visayans just called it habul (woven stuff) or halong (abaca) or even hulun (sash).

The usual male headdress was the pudong, a turban, though in Panay both men and women also wore a head cloth or bandana called saplung. Commoners wore pudong of rough abaca cloth wrapped around only a few turns so that it was more of a headband than a turban and was therefore called pudong-pudong—as the crowns and diadems on Christian images were later called. A red pudong was called magalong, and was the insignia of braves who had killed an enemy. The most prestigious kind of pudong, limited to the most valiant, was, like their G-strings, made of pinayusan, a gauze-thin abaca of fibers selected for their whiteness, tie-dyed a deep scarlet in patterns as fine as embroidery, and burnished to a silky sheen. Such pudong were lengthened with each additional feat of valor: real heroes therefore let one end hang loose with affected carelessness. Women generally wore a kerchief, called tubatub if it was pulled tight over the whole head; but they also had a broad-brimmed hat called sayap or tarindak, woven of sago-palm leaves. Some were evidently signs of rank: when Humabon's queen went to hear mass during Magellan's visit, she was preceded by three girls carrying one of her hats. A headdress from Cebu with a deep crown, used by both sexes for travel on foot or by boat, was called sarok, which actually meant to go for water.[23]

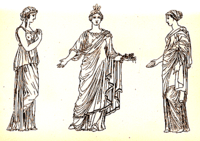

Classical Greece

Fabric in Ancient Greece was woven on a warp-weighted loom. The first extant image of weaving in western art is from a terracotta lekythos in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. The vase, c. 550-530 B.C.E., depicts two women weaving at an upright loom. The warp threads, which run vertically to a bar at the top, are tied together with weights at the bottom, which hold them taut. The woman on the right runs the shuttle containing the weaving thread across the middle of the warp. The woman on the left uses a beater to consolidate the already-woven threads.[24]

Dress in classical antiquity favored wide, unsewn lengths of fabric, pinned and draped to the body in various ways.

Ancient Greek clothing consisted of lengths of wool or linen, generally rectangular and secured at the shoulders with ornamented pins called fibulae and belted with a sash. Typical garments were the peplos, a loose robe worn by women; the chlamys, a cloak worn by men; and the chiton, a tunic worn by both men and women. Men's chitons hung to the knees, whereas women's chitons fell to their ankles. A long cloak called a himation was worn over the peplos or chlamys.

The toga of ancient Rome was also an unsewn length of wool cloth, worn by male citizens draped around the body in various fashions, over a simple tunic. Early tunics were two simple rectangles joined at the shoulders and sides; later tunics had sewn sleeves. Women wore the draped stola or an ankle-length tunic, with a shawl-like palla as an outer garment. Wool was the preferred fabric, although linen, hemp, and small amounts of expensive imported silk and cotton were also worn.

Iron Age Europe

The Iron Age is broadly identified as stretching from the end of the Bronze Age around 1200 BC to 500 AD and the beginning of the Medieval period. Bodies and clothing have been found from this period, preserved by the anaerobic and acidic conditions of peat bogs in northwestern Europe. A Danish recreation of clothing found with such bodies indicates woven wool dresses, tunics and skirts.[25] These were largely unshaped and held in place with leather belts and metal brooches or pins. Garments were not always plain, but incorporated decoration with contrasting colours, particularly at the ends and edges of the garment. Men wore breeches, possibly with lower legs wrapped for protection, although Boucher states that long trousers have also been found.[26] Warmth came from woollen shawls and capes of animal skin, probably worn with the fur facing inwards for added comfort. Caps were worn, also made from skins, and there was an emphasis on hair arrangements, from braids to elaborate Suebian knots.[27] Soft laced shoes made from leather protected the foot.

Medieval clothing and textiles

The history of Medieval European clothing and textiles has inspired a good deal of scholarly interest in the 21st century. Elisabeth Crowfoot, Frances Pritchard, and Kay Staniland authored Textiles and Clothing: Medieval Finds from Excavations in London, c.1150-c.1450 (Boydell Press, 2001). The topic is also the subject of an annual series, Medieval Clothing and Textiles (Boydell Press), edited by Robin Netherton and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Emeritus Professor of Anglo-Saxon Culture at the University of Manchester.

Byzantium

The Byzantines made and exported very richly patterned cloth, woven and embroidered for the upper classes, and resist-dyed and printed for the lower.[28] By Justinian's time the Roman toga had been replaced by the tunica, or long chiton, for both sexes, over which the upper classes wore various other garments, like a dalmatica (dalmatic), a heavier and shorter type of tunica; short and long cloaks were fastened on the right shoulder.

Leggings and hose were often worn, but are not prominent in depictions of the wealthy; they were associated with barbarians, whether European or Persian.[29]

Early medieval Europe

European dress changed gradually in the years 400 to 1100. People in many countries dressed differently depending on whether they identified with the old Romanised population, or the new invading populations such as Franks, Anglo-Saxons, and Visigoths. Men of the invading peoples generally wore short tunics, with belts, and visible trousers, hose or leggings. The Romanised populations, and the Church, remained faithful to the longer tunics of Roman formal costume.[30]

The elite imported silk cloth from the Byzantine, and later Muslim, worlds, and also probably cotton. They also could afford bleached linen and dyed and simply patterned wool woven in Europe itself. But embroidered decoration was probably very widespread, though not usually detectable in art. Lower classes wore local or homespun wool, often undyed, trimmed with bands of decoration, variously embroidery, tablet-woven bands, or colorful borders woven into the fabric in the loom.[31][32]

High Middle Ages and the rise of fashion

Clothing in 12th and 13th century Europe remained very simple for both men and women, and quite uniform across the subcontinent. The traditional combination of short tunic with hose for working-class men and long tunic with overdress for women and upper class men remained the norm. Most clothing, especially outside the wealthier classes, remained little changed from three or four centuries earlier.[33]

The 13th century saw great progress in the dyeing and working of wool, which was by far the most important material for outerwear. Linen was increasingly used for clothing that was directly in contact with the skin. Unlike wool, linen could be laundered and bleached in the sun. Cotton, imported raw from Egypt and elsewhere, was used for padding and quilting, and cloths such as buckram and fustian.

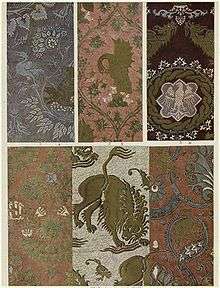

Crusaders returning from the Levant brought knowledge of its fine textiles, including light silks, to Western Europe. In Northern Europe, silk was an imported and very expensive luxury.[34] The well-off could afford woven brocades from Italy or even further afield. Fashionable Italian silks of this period featured repeating patterns of roundels and animals, deriving from Ottoman silk-weaving centres in Bursa, and ultimately from Yuan Dynasty China via the Silk Road.[35]

Cultural and costume historians agree that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable "fashion" in Europe.[36][37] From this century onwards, Western fashion changed at a pace quite unknown to other civilizations, whether ancient or contemporary.[38] In most other cultures, only major political changes, such as the Muslim conquest of India, produced radical changes in clothing, and in China, Japan, and the Ottoman Empire fashion changed only slightly over periods of several centuries.[39]

In this period, the draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the beginnings of tailoring, which allowed clothing to more closely fit the human form, as did the use of lacing and buttons.[40] A fashion for mi-parti or parti-coloured garments made of two contrasting fabrics, one on each side, arose for men in mid-century,[41] and was especially popular at the English court. Sometimes just the hose would have different colours on each leg.

Renaissance and early modern period

Renaissance Europe

Wool remained the most popular fabric for all classes, followed by linen and hemp.[35] Wool fabrics were available in a wide range of qualities, from rough undyed cloth to fine, dense broadcloth with a velvety nap; high-value broadcloth was a backbone of the English economy and was exported throughout Europe.[42] Wool fabrics were dyed in rich colours, notably reds, greens, golds, and blues.[35]

Silk-weaving was well established around the Mediterranean by the beginning of the 15th century, and figured silks, often silk velvets with silver-gilt wefts, are increasingly seen in Italian dress and in the dress of the wealthy throughout Europe. Stately floral designs featuring a pomegranate or artichoke motif had reached Europe from China in the previous century and became a dominant design in the Ottoman silk-producing cities of Istanbul and Bursa, and spread to silk weavers in Florence, Genoa, Venice, Valencia and Seville in this period.[35][43]

As prosperity grew in the 15th century, the urban middle classes, including skilled workers, began to wear more complex clothes that followed, at a distance, the fashions set by the elites. National variations in clothing increased over the century.[44]

Early Modern Europe

By the first half of the 16th century, the clothing of the Low Countries, German states, and Scandinavia had developed in a different direction than that of England, France, and Italy, although all absorbed the sobering and formal influence of Spanish dress after the mid-1520s.[45]

Elaborate slashing was popular, especially in Germany. Black was increasingly worn for the most formal occasions. Bobbin lace arose from passementerie in the mid-16th century, probably in Flanders.[46] This century also saw the rise of the ruff, which grew from a mere ruffle at the neckline of the shirt or chemise to immense cartwheel shapes. At their most extravagant, ruffs required wire supports and were made of fine Italian reticella, a cutwork linen lace.

By the turn of the 17th century, a sharp distinction could be seen between the sober fashions favored by Protestants in England and the Netherlands, which still showed heavy Spanish influence, and the light, revealing fashions of the French and Italian courts.

The great flowering of needlelace occurred in this period. Geometric reticella deriving from cutwork was elaborated into true needlelace or punto in aria (called in England "point lace"), which reflected the scrolling floral designs popular for embroidery. Lacemaking centers were established in France to reduce the outflow of cash to Italy.[46][47][48]

According to Dr. Wolf D. Fuhrig, "By the second half of the 17th century, Silesia had become an important economic pillar of the Habsburg monarchy, largely on the strength of its textile industry."[49]

Mughal India

Mughal India (16th to 18th centuries) was the most important center of manufacturing in international trade up until the 18th century.[50] Up until 1750, India produced about 25% of the world's industrial output.[51] The largest manufacturing industry in Mughal India was textile manufacturing, particularly cotton textile manufacturing, which included the production of piece goods, calicos, and muslins, available unbleached and in a variety of colours. The cotton textile industry was responsible for a large part of India's international trade.[52] India had a 25% share of the global textile trade in the early 18th century.[53] Indian cotton textiles were the most important manufactured goods in world trade in the 18th century, consumed across the world from the Americas to Japan.[50] The most important center of cotton production was the Bengal Subah province, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka.[54]

Bengal accounted for more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks imported by the Dutch from Asia,[55] Bengali silk and cotton textiles were exported in large quantities to Europe, Indonesia, and Japan,[56] and Bengali muslin textiles from Dhaka were sold in Central Asia, where they were known as "daka" textiles.[54] Indian textiles dominated the Indian Ocean trade for centuries, were sold in the Atlantic Ocean trade, and had a 38% share of the West African trade in the early 18th century, while Indian calicos were major force in Europe, and Indian textiles accounted for 20% of total English trade with Southern Europe in the early 18th century.[51]

In early modern Europe, there was significant demand for textiles from Mughal India, including cotton textiles and silk products.[52] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughal Indian textiles and silks. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Mughal India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia.[55]

Emphasis was placed on the adornment[57] of women. Even though the purdah was made compulsory for the Mughal women, we see that this did not stop themselves from experimenting in style and attire. Abul Fazal mentions that there were sixteen components that adorned a woman. These not only included clothing but also other aspects like that of oiling the body and iqtar. Mughal women wore long loose jamas with full sleeves and in winters it was accompanied by a Qaba or a Kashmir shawl used as a coat. Women were very fond of their perfumes and scents. Jewellery in the Mughal tradition signified not only religious values but also style statements.

Pre-Colonial North America

Across North America, native people constructed clothing using natural fibers such as cotton and agave as well as leather skins from animals such as deer or beavers. When traders and colonists came from Europe, they brought with them sheep and travelers highly valued the beaver pelts in particular for their warmth. Beaver pelt trade was one of the first commercial endeavors of colonial North America and a cause of the Beaver Wars.

Enlightenment and the Colonial period

During the 18th century, distinction was made between full dress worn at Court and for formal occasions, and undress or everyday, daytime clothes. As the decades progressed, fewer and fewer occasions called for full dress which had all but disappeared by the end of the century. Full dress followed the styles of the French court, where rich silks and elaborate embroidery reigned. Men continued to wear the coat, waistcoat and breeches for both full dress and undress; these were now sometimes made of the same fabric and trim, signalling the birth of the three-piece suit.

Women's silhouettes featured small, domed hoops in the 1730s and early 1740s, which were displaced for formal court wear by side hoops or panniers which later widened to as much as three feet to either side at the court of Marie Antoinette. Fashion reached heights of fantasy and abundant ornamentation, before new enthusiasms for outdoor sports and country pursuits and a long-simmering movement toward simplicity and democratization of dress under the influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the American Revolution led to an entirely new mode and the triumph of British woollen tailoring following the French Revolution.

For women's dresses, Indian cottons, especially printed chintzes, were imported to Europe in large numbers, and towards the end of the period simple white muslin dresses were in fashion.

Industrial revolution

During the industrial revolution, fabric production was mechanised with machines powered by waterwheels and steam-engines. Production shifted from small cottage based production to mass production based on assembly line organisation. Clothing production, on the other hand, continued to be made by hand.

Sewing machines emerged in the 19th century[58] streamlining clothing production.

Textiles were not only made in factories. Before this, they were made in local and national markets. Dramatic change in transportation throughout the nation is one source that encouraged the use of factories. New advances such as steamboats, canals, and railroads lowered shipping costs which caused people to buy cheap goods that were produced in other places instead of more expensive goods that were produced locally. Between 1810 and 1840, the development of a national market prompted manufacturing which tripled the output's worth. This increase in production created a change in industrial methods, such as the use of factories instead of hand made woven materials that families usually made.[59]

The vast majority of the people who worked in the factories were women. Women went to work in textile factories for a number of reasons. Some women left home to live on their own because of crowding at home; or to save for future marriage portions. The work enabled them to see more of the world, to earn something in anticipation of marriage, and to ease the crowding within the home. They also did it to make money for family back home. The money they sent home was to help out with the trouble some of the farmers were having. They also worked in the millhouses because they could gain a sense of independence and growth as a personal goal.[60]

20th-century developments

The 20th century is marked by new applications for textiles as well as inventions in synthetic fibers and computerized manufacturing control systems.

Unions and education

In the early 20th century, workers in the clothing and textile industries became unionized in the United States. Later in the 20th century, the industry had expanded to such a degree that such educational institutions as UC Davis established a Division of Textiles and Clothing,[61] The University of Nebraska-Lincoln also created a Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design that offers a Masters of Arts in Textile History,[62] and Iowa State University established a Department of Textiles and Clothing that features a History of costume collection, 1865–1948.[63] Even high school libraries have collections on the history of clothing and textiles.[64]

New applications

The changing lifestyles, activities, and demands of the 20th century favored clothing producers who could more effectively make their products have desired properties, such as increased strength, elasticity, or durability. These properties may be implemented through mechanical solutions, such as different weaving and knitting patterns, by modifications to the fibers, or by finishing (textiles) of the textiles. Since the 1960s, it has been possible to finish textiles to resist stains, flames, wrinkles, and microbial life. Advancement in dye technology allowed for coloring of previously difficult-to-dye natural fibers and synthetic fibers.[65]

Synthetic fibers

Following the invention of plastics by petroleum and chemical corporations, fibers could now be made synthetically. Advancements in fiber spinning actuators and control systems allow control over fiber diameter and shape, so Synthetic fibers, may be engineered with more precision than natural fibers. Fibers invented between 1930 and 1970 include nylon, PTFE, polyester, Spandex, and Kevlar. Clothing producers soon adopted synthetic fibers, often using blends of different fibers for optimized properties.[65] Synthetic fibers can be knit and woven similarly to natural fibers.

Automation and numeric control

The early 20th century continued the advances of the Industrial Revolution. In The procedural loops required for mechanized textile knitting and weaving already used logic were encoded in punch-cards and tapes. Since the machines were already computers, the invention of small-scale electronics and microcontrollers did not immediately change the possible functions of these machines. In the 1960s, existing machines became outfitted with computerized numeric control (CNC) systems, enabling more accurate and efficient actuation. In 1983, Bonas Machine Company Ltd. presented the first computer-controlled, electronic, Jacquard loom.[66] In 1988, the first US patent was awarded for a "pick and place" robot.[67] Advancements such as these changed the nature of work for machine operators, introducing computer literacy as a skill alongside machine literacy. Advances in sensing technology and data processing of the 20th century include the spectrophotometer for color matching and automatic inspection machines.

21st century issues

In the 2010s, the global textile industry has come under fire for unsustainable practices. The textile industry is shown to have a 'negative environmental impact at most stages in the production process.[68]

Global trade of secondhand clothing have promise for reducing landfill use, however international relations and challenges to textile recycling keep the market small compared to total clothing use.[69][70]

Advancements in textile treatment, coating, and dyes have unclear affects in human health, and textile contact dermatitis is increasing in prevalence among textile workers and clothing consumers.[71][72]

Scholars have identified an increase in the rate at which western consumers purchase new clothing, as well as a decrease in the lifespan of clothing. Fast fashion has been suggested to contribute to increased levels of textile waste.[73]

The worldwide market for textiles and apparel exports in 2013 according to United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database stood at $772 billion.[74]

In 2016, the largest apparel exporting nations were China ($161 billion), Bangladesh ($28 billion), Vietnam ($25 billion), India ($18 billion), Hong Kong ($16 billion), Turkey ($15 billion) and Indonesia ($7 billion).[75]

See also

References

- Creativity In The Textile Industries: A Story From Pre-History To The 21st century Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Textileinstitutebooks.com. Retrieved on 1 January 2012.

- Jenkins, pp. 1–6.

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1992) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press ISBN 0-691-00224-X

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1995) Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years: Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times, W. W. Norton & Company ISBN 0-393-31348-4

- Bellis, Mary (1 February 2016). "The History of Clothing – How Did Specific Items of Clothing Develop?". The About Group. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- "Archaeologists Discover Oldest-known Fiber Materials Used By Early Humans". Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- Forensic Photography Brings Color Back To Ancient Textiles Archived 23 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Researchnews.osu.edu. Retrieved on 1 January 2012.

- Jenkins, D. T (1 January 2003). The Cambridge history of western textiles. Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0521341073. OCLC 48475172.

- Elisseeff, Vadime, The Silk Roads: Highways of Culture and Commerce, UNESCO Publishing / Berghahn Books, 2001, ISBN 978-92-3-103652-1

- Jenkins, pp. 39–47

- Drimba, Ovidiu (1985). Istoria Culturii și Civilizației (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 79.

- Laver, James (2020). Costume and Fashion A Concise History. Thames & Hudson. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-500-20449-8.

- Jarrige, Jean-François; Meadow, Richard H. (8 May 1980). "The Antecedents of Civilization in the Indus Valley". Scientific American. 243 (2): 122–137. Bibcode:1980SciAm.243b.122J. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0880-122. JSTOR 24966394.

- Lal, Braj Basi (2009). How deep are the roots of Indian civilization? : archaeology answers in SearchWorks catalog. searchworks.stanford.edu. ISBN 9788173053764. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Jenkins, pp. 30–39

- Tang, Chi and Miao, Liangyun, "Zhongguo Sichoushi" ("History of Silks in China") Archived 23 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Encyclopedia of China, 1st ed.

- "Textile Exhibition: Introduction". Asian art. Archived from the original on 8 September 2007. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- (in French) Charles Meyer, Des mûriers dans le jardine du mandarin, Historia, no. 648, December 2000.

- Cameron, J. (2011). Iron and cloth across the Bay of Bengal: new data from Tha Kae, central Thailand. Antiquity, 85(328).

- Liddell, Jill, The story of the Kimono, E. P. Dutton New Zork, 1989, ISBN 0-525-24574-X

- Zamanaka, Norio, The Book of Kimono, Kodansha International, 1986, ISBN 0-87011-785-8

- Slade, T. (2009). Japanese fashion a cultural history (English ed.). Oxford: Berg.

- "Pinoy-Culture ~ A Filipino Cultural & History Blog - Pre-Colonial Traditional Clothing (Note: Though..." Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Jenkins, D. T (1 January 2003). The Cambridge history of western textiles. "Industries of Early Historic Europe and the Mediterranean: The Greeks". Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0521341073. OCLC 48475172.

- The Tollund Man – Clothes and Fashion Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Tollundman.dk. Retrieved on 1 January 2012.

- Boucher, p. 28

- Archaeology Magazine – Bodies of the Bogs – Clothing and Hair Styles Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Archaeology.org. Retrieved on 1 January 2012.

- Payne et al. (1992)

- Payne et al. (1992) p. 128.

- Piponnier & Mane, pp. 114–115

- Owen-Crocker, Gale R., Dress in Anglo-Saxon England, revised edition, Boydell Press, 2004, ISBN 1-84383-081-7 pp. 309–315

- Østergård, Else, Woven into the Earth: Textiles from Norse Greenland, Aarhus University Press, 2004, ISBN 87-7288-935-7

- Piponnier & Mane, p. 39

- Donald King in Jonathan Alexander & Paul Binski (eds), Age of Chivalry, Art in Plantagenet England, 1200–1400, p. 157, Royal Academy/Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1987 ISBN 0-297-79182-6

- Koslin, Désirée, "Value-Added Stuffs and Shifts in Meaning: An Overview and Case-Study of Medieval Textile Paradigms", in Koslin and Snyder, Encountering Medieval Textiles and Dress, pp. 237–240 ISBN 0-312-29377-1

- Laver, James: The Concise History of Costume and Fashion, Abrams, 1979, p. 62 ISBN 0-684-13522-1

- Braudel, p. 317

- "The birth of fashion", in Boucher, p. 192

- Braudel, pp. 312, 313, 323

- Singman, Jeffrey L. and Will McLean: Daily Life in Chaucer's England, p. 93. Greenwood Press, London, 2005 ISBN 0-313-29375-9

- Black, J. Anderson, and Madge Garland: A History of Fashion, Morrow, 1975, ISBN 0-688-02893-4, p. 122

- Crowfoot, Elizabeth, Frances Prichard and Kay Staniland, Textiles and Clothing c. 1150 -c. 1450, Museum of London, 1992, ISBN 0-11-290445-9

- "Length of Velvet, Late 15th century". Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2012.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link). the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York

- Boucher

- Boucher, pp. 219, 244

- Montupet, Janine, and Ghislaine Schoeller: Lace: The Elegant Web, ISBN 0-8109-3553-8

- Berry, Robin L.: "Reticella: a walk through the beginnings of Lace" Archived 14 June 2009 at WebCite (2004)

- Kliot, Jules and Kaethe: The Needle-Made Lace of Reticella, Lacis Publications, Berkeley, CA, 1994. ISBN 0-916896-57-9.

- Dr. Wolf D. Fuhrig, "German Silesia: Doomed to Extinction," Heritage: For German-Americans who want to be informed (May 2007): 1.

- Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- Jeffrey G. Williamson, David Clingingsmith (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- Karl J. Schmidt (2015), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, page 100, Routledge

- Angus Maddison (1995), Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992, OECD, p. 30

- Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202, University of California Press

- Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237-240, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Spindel, Loom, and Needle – History of the Textile Industry

- W. J. Rorabaugh (17 September 1981). The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition. Oxford University Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 978-0-19-502990-1. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- Thomas Dublin (August 1995). Transforming women's work: New England lives in the industrial revolution. Cornell University Press. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-0-8014-8090-4. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- UC Davis Department of Textiles and Clothing Archived 27 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine History

- University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Textiles, Clothing and Design M.A. in Textile History Archived 19 October 2010 at WebCite. (PDF) . Retrieved on 1 January 2012.

- Iowa State University Archived 15 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine College of Family and Consumer Sciences. Department of Textiles and Clothing History of costume collection, 1865–1948, n. d.

- Union-Endicott High School Library Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Clothing and Textiles – Fashion History

- Sara J. Kadolph; Sara B. Marcketti (2016). Textiles, 12th edition. Pearson.

- Bonas.co.uk

- US 4872258A, Philip A Ragard, published 1988-09-22

- Keith Slater (2003). Environmental Impact of Textiles: Production, Process, and Protection. Woodhead.

- Pietra Rivoli (2015). travels of a t-shirt in the global economy, 2nd edition. Wiley.

- Gustav Sandin; Greg M. Peters (2018). "Environmental Impact of Textile Use and Recycling: A Review". Journal of Cleaner Production.

- Farzad Alinaghi; et al. (29 October 2018). "Prevalence of Contact Allergy in the General Population: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Contact Dermatitis.

- Motunrayo Mobolaji-Lawal; Susan Nedorost (1 July 2015). "The Role of Textile in Dermatitis: An Update". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports.

- Jerri-Lynn Scofield (10 April 2017). "Faster Fashion Cycle Accelerates". naked capitalism.

- "India world's second largest textiles exporter: UN Comtrade". Economic Times. 2 June 2014.

- "Exporters hardly grab orders diverted from China". thedailystar.net. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

Bibliography

- Boucher, François. 20,000 Years of Fashion: The history of costume and personal adornment. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987 ISBN 0-8109-1693-2

- Jenkins, David, ed.: The Cambridge History of Western Textiles, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-34107-8

- Payne, Blanche; Winakor, Geitel; Farrell-Beck Jane (1992) The History of Costume, from the Ancient Mesopotamia to the Twentieth Century, 2nd Edn, HarperCollins ISBN 0-06-047141-7

- Piponnier, Françoise, and Perrine Mane; Dress in the Middle Ages; Yale UP; 1997; ISBN 0-300-06906-5

Further reading

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Dress: Clothing and Society 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996. ISBN 0-8109-6317-5

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion: the cut and construction of clothes for men and women 1560–1620, Macmillan 1985. Revised edition 1986. (ISBN 0-89676-083-9)

- Arnold, Janet: Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd, W S Maney and Son Ltd, Leeds 1988. ISBN 0-901286-20-6

- Braudel, Fernand, Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th centuries, Vol 1: The Structures of Everyday Life, William Collins & Sons, London 1981

- Darwin, George H., "Development in Dress", Macmillan's magazine, vol. 26, May to Oct. 1872, pages 410–416

- Favier, Jean, Gold and Spices: The Rise of Commerce in the Middle Ages, London, Holmes and Meier, 1998, ISBN 0-8419-1232-7

- Gordenker, Emilie E.S.: Van Dyck and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture, Brepols, 2001, ISBN 2-503-50880-4

- Kõhler, Carl: A History of Costume, Dover Publications reprint, 1963, from 1928 Harrap translation from the German, ISBN 0-486-21030-8

- Lee, John S.: The Medieval Clothier, Woodbridge, Boydell, 2018, ISBN 9781783273171

- Lefébure, Ernest: Embroidery and Lace: Their Manufacture and History from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Day, London, H. Grevel and Co., 1888, ed. by Alan S. Cole, at Online Books , retrieved 14 October 2007

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 1, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2005, ISBN 1-84383-123-6

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 2, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press, 2006, ISBN 1-84383-203-8

- Netherton, Robin, and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Clothing and Textiles, Volume 3, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, the Boydell Press 2007, ISBN 978-1-84383-291-1

- Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, 1965. No ISBN for this edition; ASIN B0006BMNFS

- Sylvester, Louise M., Mark C. Chambers and Gale R. Owen-Crocker, editors, Medieval Dress and Textiles in Britain: A Multilingual Sourcebook, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, and Rochester, NY, Boydell Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1-84383-932-3

- Watt, James C.Y.; Wardwell, Anne E. (1997). When silk was gold: Central Asian and Chinese textiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870998256.

External links

- Textile production in Europe, 1600–1800, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Spindle, Loom, and Needle – History of the Textile Industry

- Australian Museum of Clothing And Textiles Inc. at the Wayback Machine (archived 27 October 2009) – Why have a Museum of Clothing and Textiles?

- Linking Anthropology and History in Textiles and Clothing Research: The Ethnohistorical Method by Rachel K. Pannabecker – from Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, Vol. 8, No. 3, 14–18 (1990)

- The drafting history of the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing

- American Women's History: A Research Guide Clothing and Fashion

- All Sewn Up: Millinery, Dressmaking, Clothing and Costume

- Gallery of English Medieval Clothing from 1906 by Dion Clayton Calthrop

.jpg)