1650–1700 in Western European fashion

Fashion in the period 1660–1700 in Western European clothing is characterized by rapid change. The style of this era is known as Baroque. Following the end of the Thirty Years' War and the Restoration of England's Charles II, military influences in men's clothing were replaced by a brief period of decorative exuberance which then sobered into the coat, waistcoat and breeches costume that would reign for the next century and a half. In the normal cycle of fashion, the broad, high-waisted silhouette of the previous period was replaced by a long, lean line with a low waist for both men and women. This period also marked the rise of the periwig as an essential item of men's fashion.

Women's fashion

%2C_Duchess_of_Cleveland_by_John_Michael_Wright.jpg)

Overview

The wide, high-waisted look of the previous period was gradually superseded by a long vertical line, with horizontal emphasis at the shoulder. Full, loose sleeves ended just below the elbow at mid century and became longer and tighter in keeping with the new trend. The body was tightly corseted, with a low, broad neckline and dropped shoulder. In later decades, the overskirt was drawn back and pinned up to display the petticoat, which was heavily decorated.

Spanish court fashion remained out of step with the fashions that arose in France and England, and prosperous Holland also retained its own modest fashions, especially in headdress and hairstyles, as it had retained the ruff in the previous period.

Romantic negligence

A daring new fashion arose for having one's portrait painted in undress, wearing a loosely fastened gown called a nightgown over a voluminous chemise, with tousled curls. The style is epitomized by the portraits of Peter Lely, which derive from the romanticized style originated by Anthony van Dyck in the 1630s. The clothing in these portraits is not representative of what was worn on the street or at court.[1][2]

Mantua

The mantua or manteau was a new fashion that arose in the 1680s. Instead of a bodice and skirt cut separately, the mantua hung from the shoulders to the floor (in the manner of dresses of earlier periods) started off as the female version of the men's Banyan, worn for 'undress' wear. Gradually it developed into a draped and pleated dress and eventually evolved into a dress worn looped and draped up over a contrasting petticoat and a stomacher. The mantua-and-stomacher resulted in a high, square neckline in contrast to the broad, off-the-shoulder neckline previously in fashion. The new look was both more modest and covered-up than previous fashions and decidedly fussy, with bows, frills, ribbons, and other trim, but the short string of pearls and pearl earrings or eardrops worn since the 1630s remained popular.

The mantua, made from a single length of fabric pleated to fit with a long train, was ideal for showing the designs of the new elaborately patterned silks that replaced the solid-colored satins popular in mid-century.[3]

Hunting and riding dress

In a June 1666 diary entry, Samuel Pepys describes the Maids of Honour in their riding habits of mannish coats, doublets, hats, and periwigs, "so that, only for a long petticoat dragging under their men's coats, nobody could take them for women in any point whatever". For riding side-saddle, the costume had a long, trailing petticoat or skirt. This would be looped up or replaced by an ankle-length skirt for shooting or walking.

Hairstyles and headgear

Early in the period, hair was worn in a bun at the back of the head with a cluster of curls framing the face. The curls grew more elaborate through the 1650s, then longer, until curls were hanging gracefully on the shoulder. In the 1680s hair was parted in the center with height over the temples, and by the 1690s hair was unparted, with rows of curls stacked high over the forehead.

This hairstyle was often topped with a fontange, a frilly cap of lace wired to stand in vertical tiers with streamers to either side, named for a mistress of the French King. This was popular from the 1690s to the first few years of the 18th century.

Style gallery 1650s

1 – 1650

1 – 1650 2 – 1652

2 – 1652 3 – 1652

3 – 1652 4 – 1653

4 – 1653_-_Skoklosters_slott_-_88963.tif.jpg) 6 - 1655

6 - 1655 7 – 1658

7 – 1658 8 – 1658

8 – 1658 9 – 1659

9 – 1659

- German fashion of 1650 shows a smooth, tight, conical satin bodice with a dropped shoulder. Slashed sleeves are caught with jeweled clasps over voluminous chemise sleeves.

- Margareta Maria de Roodere wears a salmon-colored gown. A sheer scarf is knotted into a collar around her shoulders, and her white sleeve linings are fastened back with a covered button, 1652.

- Mary, Princess of Orange wears a satin gown with a long pointed bodice and a satin petticoat. The many tiny pleats that gather in her skirt can be seen, 1652.

- Maria Theresa of Spain wears the guardainfante, which, in Spain, was adapted late and retained it long after it had disappeared elsewhere. The Infanta's hairstyle is also typical of the Spanish court, 1653.

- The Swedish countess Beata Elisabet von Königsmarck wears a white silk gown with a long tight bodice, flat skirt, wide double puffed sleeves, bare shoulders and a deep cleavage. The dress is decorated with blue ribbons and a blue shawl draped around the breasts. She has pearls, and her hair is braided in a knot in the back, but is worn in loose curls over her ears.

- Young Dutch girl wears a rose jacket-bodice and a plain pink petticoat. Her hair is worn in a wound braid with small curls over her ears. 1658–60.

- Details of Dutch fashion of 1658 include a string of pearls tied with a black ribbon, a jack-bodice with matching skirt, pleated sleeves, and dropped shoulder.

- The Infanta Margarita of Spain is shown, when eight years old, wearing the guardainfante, 1659.

Style gallery 1660–1680

- 1 - 1660s

2 – c.1660

2 – c.1660 3 – 1662

3 – 1662 4 – 1663

4 – 1663 5 - 1665

5 - 1665 6 – 1666

6 – 1666 7 – 1670

7 – 1670_by_Juan_Carre%C3%B1o_de_Miranda.jpg) 8 – 1670

8 – 1670 9 – 1671–74

9 – 1671–74 10 – 1670s

10 – 1670s

- English court dress from the 1660s, made of silver tissue and decorated with applied parchment lace.[4] From the Fashion Museum, Bath.

- Peter Lely portrays Two Ladies of the Lake Family wearing satin dresses over shifts or chemises with voluminous sleeves. Their hair is worn in masses of ringlets to the shoulders on either side, and both wear large pearl eardrops. The lack of a modesty piece at the chest is characteristic of the romantic style. It was at this period that women exposed their breasts for the first time.

- Dutch lacemaker's jacket-bodice has a dropped shoulder line and full, three-quarter length sleeves cartridge-pleated at shoulder and cuff. Her indoor cap has a circular back and hood is embroidered. Her shoes have thick heels and square toes, now somewhat old-fashioned.

- The very long pointed bodice of c. 1663 is shown clearly in this portrait of a woman playing a viola de gamba. The sleeve is pleated into the dropped should and into the cuff.

- Inés de Zúñiga, Countess of Monterrey is a beautiful example of typical court fashion in Spain.

- The Infanta Margarita of Spain is shown here wearing a mourning dress of unrelieved black with long sleeves, cloak and hood. She wears her hair parted to one side and severely bound in braids, 1666.

- Two English ladies wear dresses with short sleeves over chemise sleeves gathered into three puffs. The long bodice front with curving bands of vertical trim is characteristic of 1670.

- Maria Theresa of Spain wears enormous sleeves, bare shoulders, large pearls, a large feather, and has a mass of loose waves.

- Lingering Puritan influence appears in this portrait of a Boston matron: she wears a lace-trimmed linen collar that covers her from the neck down with the fashionable short string of pearls, and she covers her hair with hood-like cap, 1671–74.

- Empress Eleonore of Pfalz-Neuburg wears a brocade dress with a very low waist and elbow-length sleeves gathered in puffs as was typical of court fashions during the 1670s.

Style gallery 1680s–1690s

1 – 1680

1 – 1680 2 – 1680s–90s

2 – 1680s–90s 3 – 1688

3 – 1688 4 – c.1690

4 – c.1690 5 – c.1690

5 – c.1690 6 – 1685–90

6 – 1685–90 7 – 1690s

7 – 1690s.jpg) 8 – 1698

8 – 1698 9 - 1690s

9 - 1690s

- Mary of Modena, second wife of James II of England, wears a dress fastened with jeweled clasps over a simple chemise, 1680. Her hair curls over either temple, and long curls hang on her shoulders. This style of undress was common in portraits, but likely not so common in everyday wear.

- Dorothy Mason, Lady Brownlow in fashionable undress. Her dress is casually unfastened at the breast, and her chemise sleeves are caught up in puffs, probably with drawstrings.

- Mary II wears 1688 fashion: a mantua with elbow-length cuffed sleeves over a chemise with lace flounces at the elbow, a wired lace fontange, opera-length gloves, and pearls.

- Spanish court fashion of c. 1690 shows a long, rigidly corseted line with a broad neckline and long sleeves.

- Mary II of England. By 1690, hair was dressed high over her forehead with curls dangling behind.

- Contemporary French fashion plate of a manteau or mantua, 1685–90.

- The Electress Palatine (Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici) in hunting dress, probably mid-to-late 1690s. She wears a long, mannish coat with wide cuffs and a matching petticoat over a high-necked bodice (Pepys calls it a doublet) with long tight sleeves. She wears a lace-trimmed cravat and a tricorne hat with ostrich plumes.

- Comtesse de Mailly, 1698, wears court fashion: Her mantua has elbow-length cuffed sleeves over the lace-ruffled sleeves of her chemise. The trained skirt is looped back to reveal a petticoat. She wears elbow-length gloves and a cap with a high lace fontange. She has a fur muff on her right wrist, trimmed with a ribbon bow, and carries a fan. She wears the short string of pearls that remained fashionable throughout this period.

- The mantua from Kimberly Hall is of fine striped woolen fabric with silver-gilt embroidery, ca. 1690–1700.

Men's fashion

Overview

_-_Nationalmuseum_-_19702.tif.jpg)

With the end of the Thirty Years' War, the fashions of the 1650s and early 1660s imitated the new peaceful and more relaxed feeling in Europe. The military boots gave way to shoes, and a mania for baggy breeches, short coats, and hundreds of yards of ribbon set the style. The breeches (see Petticoat breeches) became so baggy that Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary: "And among other things, met with Mr. Townsend, who told of his mistake the other day to put both his legs through one of his Knees of his breeches, and so went all day." (April 1661) The wide breeches that made such an error possible were soon being gathered at the knee: Pepys noted, 19 April 1663 "this day put on my close-kneed coloured suit, which, with new stockings of the colour, with belt, and new gilt-handled sword, is very handsome." This era was also one of great variation and transition.

In 1666, Charles II of England, Scotland and Ireland, following the earlier example of Louis XIV of France, decreed that at court, men were to wear a long coat, a vest or waistcoat (originally called a petticoat, a term which later became applied solely to women's dress), a cravat, a periwig or wig, and breeches gathered at the knee, as well as a hat for outdoor wear. By 1680, this more sober uniform-like outfit of coat, waistcoat, and breeches became the norm for formal dress.

Coat and waistcoat

The unfitted looser fit of the 1640s continued into the 1650s. In the 1650s, sleeves ranged from above to below the elbow. The sleeves could be slashed, unslashed, or dividing into two parts and buttoned together. The length of the coat reached the waist but by the late 1650s and early 1660s, the coat became very short, only reaching the bottom of the rib cage, much like a bolero jacket. During the 1660s, the sleeves varied a lot from elbow length to no sleeves at all. The coat could be worn opened or buttoned in the front. One common factor were many yards of ribbon loops arranged on the shoulders and the lower parts of the sleeves.

A longer and rather baggy coat (still with sleeves rarely going below the elbow) made an appearance in the early 1660s and as the decade progressed became the most popular coat. By the late 1660s, an upturned cuff became popular although the sleeves had still remained above the elbows. By the 1670s, a vest or waistcoat was worn under the coat. It was usually made of contrasting, often luxurious, fabric, and might have a plain back since that was not seen under the coat. It was a long garment which by the 1680s reached just above the knees. With the end of the 1670s the sleeves became longer and the coat more fitted. The 1680s saw larger upturned cuffs and the waist of the coat became much wider. The coat could have lapels or none. This coat is known as the justacorps. The pockets on both sides of the coats were arranged horizontally or vertically (especially the mid to late 1680s) until the 1690s when the pockets were usually always arranged horizontally. The waistcoat could be sleeveless or have long sleeves. Typically, a long-sleeved waistcoat was worn in winter for added warmth. By the mid-1680s, ribbons were reduced to one side of the shoulder until by the 1690s, they were gone.

Shirt, collar and cravat

The ruffled long-sleeved white shirt remained the only constant throughout the period, although less of it was seen with the advent of the waistcoat.

During the early to mid-1650s, a rather small falling collar was in fashion. This increased in size and encompassed much of the shoulders by 1660. Cravats and jabots around the neck started to be worn during the early 1660s (initially with the falling collar). By the mid-1660s, the collar had disappeared with just the cravat remaining, sometimes tied with a small bow of ribbon. Red was the most common color for the bow, although pink, blue, and other colors were also used. By the 1670s, the bow of ribbons had increased in size and in the 1680s, the bow of ribbons became very large and intricate with many loops of ribbon. By the mid-1690s, the very large bow of ribbons was discarded. Also, a new style of cravat made its appearance in the 1690s, the Steinkerk (named after the Battle of Steenkerque in 1692). Before, the cravat was always worn flowing down the chest; the Steinkerk cravat looped through a buttonhole of the coat.

Breeches and stockings

The previous decade saw Spanish breeches as the most popular. These were stiff breeches which fell above or just below the knee and were rather moderately fitted. By the mid-1650s, in Western Europe, much looser, uncollected breeches, called petticoat breeches became the most popular. As the 1650s progressed, they became larger and looser, very much giving the impression of a lady's petticoat. They were usually decorated with many yards of ribbon around the waist and around the ungathered knee on the outside of the leg. Alongside the petticoat breeches, a collected but still loose fitted breeches called rhinegraves, were also worn. By the early 1660s, their popularity surpassed petticoat breeches. They were usually worn with an overskirt over them. The overskirt was heavily decorated with ribbon on the waist and the bottom of the skirt. Its length was usually just above the knee, but could also extend past the knee so that the rhinegraves underneath could not be seen and only the bottom of the stocking-tops was visible.

With the rising popularity of the longer coat and waistcoat, the large collected rhinegraves and overskirt were abandoned in favor of more close fitting breeches. By the late 1670s, close fitted breeches were worn with the stockings worn over them and on or above the knee, often being gartered with a garter below the knee. With the long waistcoat and stockings worn over the knee, very little of the breeches could be seen. A possible reason that the stockings were worn over the knee, was to give the impression of longer legs since the waist coat fell very low, just above the knee. The breeches tended to be of the same material as the coat. The stockings varied in color.

Footwear and accessories

Shoes again became the most popular footwear during the 1650s, although boots remained in use for riding and outdoor pursuits. Boothose, originally of linen with lace cuffs and worn over the fine silk stockings to protect them from wear, remained in fashion even when boots lost their popularity. Boothose lasted well in the mid-1660s, attached right under where the rhinegraves were gathered below the knee, or fashionably slouched and unfastened. Shoes from the 1650s through the 1670s tended to be square toed and slightly long in appearance. Usually the shoes were tied with ribbon and decorated with bows. By the 1680s, the shoe became a bit more fitted; the heel increased in height (with red heels being very popular, especially for attendance at Court), and only a small ribbon if any remained.

The baldric (a sword hanger worn across one shoulder) was worn until the mid-1680s, when it was replaced by the sword belt (a sword hanger worn across the hips).

Hairstyles

Throughout the period, men wore their hair long with curls well past the shoulders. The bangs (fringe) were usually combed forward and allowed to flow over the forehead a bit. Although men had worn wigs for years to cover up thinning hair or baldness, the popularity of the wig or periwig as standard wardrobe is usually credited to King Louis XIV of France. Louis started to go bald at a relatively young age and had to cover up his baldness with wigs. His early wigs very much imitated what were the hairstyles of the day, but they gave a thicker and fuller appearance than natural hair. Due to the success of the wigs, other men started to wear wigs as well. By 1680, a part in the middle of the wig became the norm. The hair on either side of the part continued to grow in the 1680s until by the 1690s two very high pronounced points developed on the forehead. As well, during the 1680s, the wig was divided into three parts: the front including the center part and the long curls which fell well past the shoulders, the back of the head which was combed rather close to the head, and a mass of curls which flowed down the shoulders and back. The curls of the wig throughout the 1660s until 1700 were rather loose. Tighter curls would not make their appearance until after 1700. Every natural color of wig was possible. Louis XIV tended to favor a brown wig. His son, Monseigneur was well known for wearing blond wigs. Facial hair declined in popularity during this period although thin moustaches remained popular up until the 1680s.

Hats and headgear

Hats vary greatly during this period. Hats with very tall crowns, derived from the earlier capotain but with flat crowns, were popular until the end of the 1650s. The brims varied as well. Hats were decorated with feathers. By the 1660s, a very small hat with a very low crown, little brim, and large amount of feathers was popular among the French courtiers. Later in the 1660s, very large brims and moderate crowns became popular. Sometimes one side of the brim would be turned up. These continued fashionable well into the 1680s. From the 1680s until 1700, various styles and combinations of upturned brims were in fashion, from one brim upturned to three brims upturned (the tricorne). Even the angle at which the brims were situated on the head varied. Sometimes with a tricorne, the point would meet over the forehead or it would be set at a 45 degree angle from the forehead.

Style gallery 1650s

1 – 1654

1 – 1654 2 – 1654

2 – 1654_-_Nationalmuseum_-_77290.tif.jpg) 3 – 1656

3 – 1656- 4 – 1658

- Coat of 1654 has many tiny buttons on the front and sleeves, which are left unfastened below the chest and upper arm. A collared cloak trimmed with braid is worn casually over one shoulder.

- Coronation dress of Charles X of Sweden from 1654.

- Swedish industrialist Emanuel De Geer in an outfit from 1656 with linen shirt with cuffs and a doublet with slashed sleeves. Over the shoulder can be seen a baldric, and at his side a rapier.

- Dutch fashions, 1658. White boothose, petticoat breeches

Style gallery 1660s

1 – 1661

1 – 1661 2 – 1661

2 – 1661

- 1661. The short coat is worn over a voluminous shirt with wide ruffles at the cuffs and flat, curve-cornered collar, petticoat breeches.

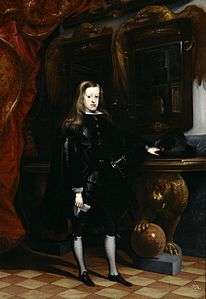

- Young Louis XIV wears a lace-bordered linen collar, sash of an order of chivalry, and a voluminous wig over his armor, 1661.

Style gallery 1670s–1690s

1 – 1671

1 – 1671 2 - 1673

2 - 1673 3 - 1684

3 - 1684 4 - c. 1690

4 - c. 1690 5 - c. 1690

5 - c. 1690

- Dutch fashions, 1671

- Wedding suit of James II of England, 1673, Victoria and Albert Museum No. 2-1995 T.711:1

- Don Luis de la Cerda, later IX Duke of Medinacelli wears the long justacorps of c. 1684

- Artist Thomas Smith, c. 1690

- A student of Leipzig in an elaborate wig, c. 1690

Spanish fashion

Spain, 1650

Spain, 1650 Spain, 1655

Spain, 1655 Spain, 1655

Spain, 1655.jpg) Spain, 1657

Spain, 1657- Spain, 1658

Spain, 1660

Spain, 1660 Spain, 1661

Spain, 1661- Spain, 1666

Spain, 1670

Spain, 1670 Spain, 1670

Spain, 1670 Spain, 1672

Spain, 1672 Spain, 1675

Spain, 1675 Spain, 1675

Spain, 1675 Spain, 1679

Spain, 1679 Spain, 1682

Spain, 1682 Spain, 1685

Spain, 1685

Children's fashion

Young boys wore skirts with doublets or back-fastening bodices until they were breeched at six to eight. They wore smaller versions of men's hats over coifs or caps. Small children's clothing featured leading strings at the shoulder.

_-_Avelar_Rebelo_(cropped).png)

Child with leading strings, 1658

Child with leading strings, 1658 Two English sisters and their brother (right), c. 1656

Two English sisters and their brother (right), c. 1656 Swiss boy, 1657

Swiss boy, 1657 Dress worn by Charles XI of Sweden in ca 1660.

Dress worn by Charles XI of Sweden in ca 1660. English boy, 1661

English boy, 1661 Young boy's dress, 1660s-70s

Young boy's dress, 1660s-70s English boys, 1670

English boys, 1670 Swiss girl, 1682

Swiss girl, 1682

Working class clothing

Dutch fish seller and housewife, 1661

Dutch fish seller and housewife, 1661 Dutch schoolmaster and children, 1662

Dutch schoolmaster and children, 1662 Checking for lice, 1662

Checking for lice, 1662 Dutch villagers, 1673

Dutch villagers, 1673

Notes

- Gordenker, Van Dyck and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture

- de Marly, "Undress in the Œuvre of Lely"

- Ribeiro, Aileen, on the origins of the mantua in the late 17th century, in Dress in Eighteenth Century Europe 1715–1789; Ashelford, Jane, The Art of Dress

- Clews, Rosemary (2009). Stephen Harden (ed.). Fashion Museum treasures. photography for the Fashion Museum by James Davies. London: Scala Publishers. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-857-59553-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 17th-century fashion. |

References

- Arnold, Janet: Patterns of Fashion 1 (cut and construction of women's clothing, 1660–1860), Wace 1964, Macmillan 1972. Revised metric edition, Drama Books 1977. ISBN 978-0-89676-026-4

- Ashelford, Jane: The Art of Dress: Clothing and Society 1500–1914, Abrams, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8109-6317-7

- Black, J. Anderson and Madge Garland: A History of Fashion, Morrow, 1975. ISBN 978-0-688-02893-0

- Brooke, Iris: Western European Costume II, Theatre Arts Books, 1966.

- de Marly, Diana: "Undress in the Œuvre of Lely", The Burlington Magazine, November 1978.

- Gordenker, Emilie E.S.: Van Dyck and the Representation of Dress in Seventeenth-Century Portraiture, Brepols, 2001, ISBN 978-2-503-50880-1

- Payne, Blanche: History of Costume from the Ancient Egyptians to the Twentieth Century, Harper & Row, 1965. No ISBN for this edition; ASIN B0006BMNFS

- Ribeiro, Aileen: Fashion and Fiction: Dress in Art and Literature in Stuart England, Yale, 2005, ISBN 978-0-300-10999-3

- Ribeiro, Aileen: Dress in Eighteenth-Century Europe 1715–1789, Yale University Press, 2002, ISBN 0-300-09151-6