Adoption in ancient Rome

Adoption in Ancient Rome was practiced and performed by the upper classes; a large number of adoptions were performed by the Senatorial class.[1] Succession and family legacy were very important; therefore Romans needed ways of passing down their fortune and name when unable to produce a male heir. Adoption was one of the few ways to guarantee succession, so it became a norm to adopt young males into the homes of high ranking families. Due to the Roman inheritance laws (Falcidia Lex[2]), women had very little rights or the ability to inherit fortunes. This made them less valuable for adoption. However, women were still adopted and it was more common for them to be wed to an influential family.

Causes

One of the benefits of a male heir was the ability to create ties among other high-ranking families through marriage. Senators throughout Rome had the responsibility of producing sons who could inherit their family’s title and estate. Childbirth was so unpredictable during these times and there was no way of knowing gender before birth. This caused many children to be lost in the years directly after and it was hard for the senators to control the situation. With the cost of children being high and average families having very few children, this posed a challenge for the Senators. Without a male heir, their title and estate could be forfeited. This was the leading cause for adoption in ancient Rome. It is important to note that adoption in ancient Rome was used for a number of reasons and not exclusively by Senators. The use by Senators guaranteed them a son; this gave senators the freedom to produce children more freely knowing a male heir could always be adopted if unable to produce one naturally. This also created new benefits for female babies enabling them to be given away for adoption into higher ranked families. With the reduced risk of succession issues this created opportunities for males children to marry into other high-ranking families to create powerful ties among the upper class. In the case of the lower classes, raising a large family was quite challenging. Due to the cost, this allowed them to put their children up for adoption. It would benefit both the families and the child. One famous example of this is when Lucius Aemilius put his own two sons up for adoption.[1]

Practice

In Rome, the person in charge of adoption was the male head of the household called the paterfamilias. Adoption would result in an adoption of power for the adopted child as the status of the adopting family was immediately transferred to the child. This was almost always an increase in power due to the high cost of adoption. Publius Clodius Pulcher famously used this loophole for political power in his attempt to gain control over the plebs.[3] During the Roman Republic, the same laws stood in place with only one difference; the requirement of the Senate's approval.

The actual adoption was often operated like a business contract between the two families. The adopted child took the family name as his own. Along with this, the child kept his/her original name through the form of cognomen or essentially a nickname. The adopted child also maintained previous family connections and often leveraged this politically. Due to the power disparity that normally existed between the families involved in adoption, a fee was often given to the lower family to help with replacing (in most cases) the first-born son. Another case similar to adoption was the fostering of children; this effectively took place when a paterfamilias transferred his power to another man to be left in their care.[4]

Adoption of Women

Throughout Roman history many adoptions took place but very few accounts of female adoption were recorded and preserved throughout history. With men holding the spotlight in history books and articles, it is possible that adoption of girls was more popular. However, because most of the famous adoptions were male children, female adoptions could have been wrongfully accounted. Additionally, because the legal impacts of women in ancient Rome were so minimal, it is possible that adoptions could have been more informal and therefore less accounted for in history. One of the most well known was Livia Augusta who gained this name after her adoption into the Julian family. Known mainly as the wife of Augustus. Livia played a key role during this time in the Roman Empire both as a political symbol and a role model for Roman households. Livia earned herself an honorable place among history as a great mother however some of the rumors related to potential heirs have survived throughout history.[5]

Claudia Octavia was another well known adopted woman in ancient Rome. Claudia was adopted by Claudius during his reign in 40 CE as his first and only daughter. Several years into adoption Claudius adopted Nero and arranged for the two to wed in 53 CE, this made Claudia Octavia both Nero's step sister and first wife. Claudia was banished in later years on the account of adultery with Anicetus, after her death her head was cut off and sent to Poppaea bringing much sorrow to Rome.[6]

Imperial succession

Many of Rome’s famous emperors took the throne through adoption, this was one of the few ways to avoid conflict. Among these men were Tactis Tiberius and Augustus, to name a few. Given the proven effectiveness, for a long period of time, emperors would simply adopt an heir to the throne. However, this wasn't always as easy as it may have seemed, because of the many challenges of becoming an emperor. It was challenging for Augustus when his uncle Julius Caesar was assassinated, with his sights on the throne Augustus wanted to claim it before anyone else tried to take over. Augustus was only nineteen and had never served in battle; his age was holding him back. Another issue for Augustus was Antony's attempts to take over through political scandal. With Antony controlling all of Caesar's previous powers, Augustus had few options. Very little power and his age helped Augustus decide to wait out the current turmoil and prepare for a future role within Rome.

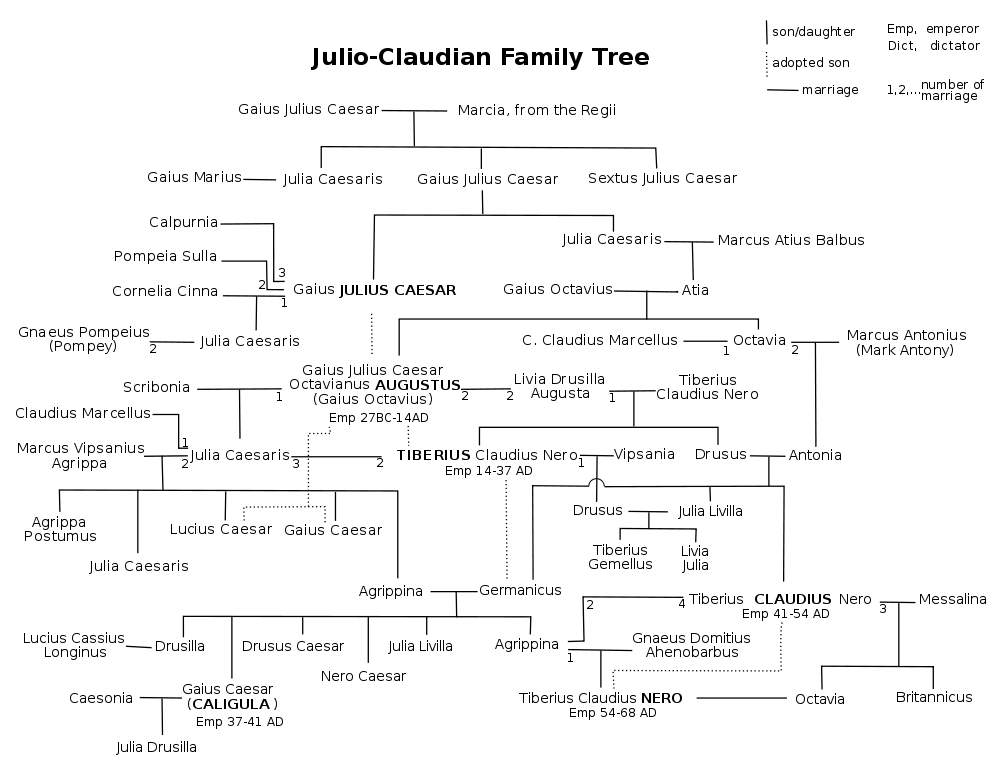

After Augustus's death finding an heir was very challenging much of this due to the number of possible heirs. You can see this clearly in Augustus's family tree with many families being woven together through marriage and adoption. This led to some complex situations such as his successor Tiberius who was both Augustus's step son and son in law. This trend would continue with Caligula who was the great grandson of both Augustus and Mark Antony as well as the great nephew of Tiberius. Many of the following emperors were related to the bloodline in some manner until the adoption of Nero by Claudius during his reign, in 54 CE Nero became the second adopted emperor of Rome.

See also

- Roman culture

- Adrogation

References

- Weigel, Richard D. (January 1978). "A Note on P. Lepidus". Classical Philology. 73 (1): 42–45. doi:10.1086/366392. ISSN 0009-837X.

- "LacusCurtius • Roman Law — Adoption (Smith's Dictionary, 1875)". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Connerty, Victor (2000). Tatum, W. J. (ed.). "Publius Clodius Pulcher". The Classical Review. 50 (2): 514–516. doi:10.1093/cr/50.2.514. ISSN 0009-840X. JSTOR 3064795.

- "Adoption in the Roman Empire". Life in the Roman Empire. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Huntsman, Eric D. (2009). "Livia Before Octavian". Ancient Society. 39: 121–169. doi:10.2143/AS.39.0.2042609. ISSN 0066-1619. JSTOR 44079922.

- Harvard University. JSTOR (Organization) Harvard University. Department of the Classics. Harvard studies in classical philology. Ginn & Co. OCLC 1057994073.