Terence

Publius Terentius Afer (/təˈrɛnʃiəs, -ʃəs/; c. 195/185 – c. 159? BC), better known in English as Terence (/ˈtɛrəns/), was a Roman African playwright during the Roman Republic. His comedies were performed for the first time around 170–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought Terence to Rome as a slave, educated him and later on, impressed by his abilities, freed him. Terence apparently died young, probably in Greece or on his way back to Rome. All of the six plays Terence wrote have survived.

One famous quotation by Terence reads: "Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto", or "I am human, and I think nothing human is alien to me."[1] This appeared in his play Heauton Timorumenos.[2]

Biography

Terence's date of birth is disputed; Aelius Donatus, in his incomplete Commentum Terenti, considers the year 185 BC to be the year Terentius was born;[3] Fenestella, on the other hand, states that he was born ten years earlier, in 195 BC.[4]

He may have been born in or near Carthage or in Greek Italy to a woman taken to Carthage as a slave. Terence's cognomen Afer suggests he lived in the territory of the Libyan tribe called by the Romans Afri near Carthage prior to being brought to Rome as a slave.[5] This inference is based on the fact that the term was used in two different ways during the republican era: during Terence's lifetime, it was used to refer to non-Carthaginian Berbers, with the term Punicus reserved for the Carthaginians.[6] Later, after the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, it was used to refer to anyone from the land of the Afri (that is, the ancient Roman province of Africa, mostly corresponding to today's Tunisia and its surroundings). The nickname Afer "[North] African" indicates that Terence hailed from ancient Libya,[7] and was therefore of Berber descent.[8]

In any case, he was sold to P. Terentius Lucanus,[9] a Roman senator, who educated him and later on, impressed by Terence's abilities, freed him. Terence then took the nomen "Terentius," which is the origin of the present form.

He was a member of the so-called Scipionic Circle.

When he was 25, Terence travelled to Greece and never returned. It is mostly believed that Terence died during the journey, but this cannot be confirmed. Before his disappearance he exhibited six comedies which are still in existence. According to some ancient writers, he died at sea.

Plays

Like Plautus, Terence adapted Greek plays from the late phases of Attic comedy. Terence wrote in a simple conversational Latin, pleasant and direct. Aelius Donatus, Jerome's teacher, is the earliest surviving commentator on Terence's work. Terence's popularity throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance is attested to by the numerous manuscripts containing part or all of his plays; the scholar Claudia Villa has estimated that 650 manuscripts containing Terence's work date from after AD 800. The mediaeval playwright Hroswitha of Gandersheim claims to have written her plays so that learned men had a Christian alternative to reading the pagan plays of Terence, while the reformer Martin Luther not only quoted Terence frequently to tap into his insights into all things human but also recommended his comedies for the instruction of children in school.[10]

Terence's six plays are:

- Andria (The Girl from Andros) (166 BC)

- Hecyra (The Mother-in-Law) (165 BC)

- Heauton Timorumenos (The Self-Tormentor) (163 BC)

- Phormio (161 BC)

- Eunuchus (161 BC)

- Adelphoe (The Brothers) (160 BC)

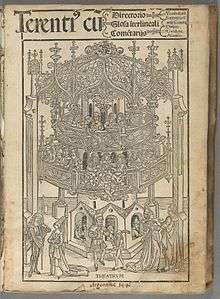

The first printed edition of Terence appeared in Strasbourg in 1470, while the first certain post-antique performance of one of Terence's plays, Andria, took place in Florence in 1476. There is evidence, however, that Terence was performed much earlier. The short dialogue Terentius et delusor was probably written to be performed as an introduction to a Terentian performance in the 9th century (possibly earlier).

Cultural legacy

Due to his clear and entertaining language, Terence's works were heavily used by monasteries and convents during the Middle Ages and The Renaissance. Scribes often learned Latin through the meticulous copying of Terence's texts. Priests and nuns often learned to speak Latin through reenactment of Terence's plays, thereby learning both Latin and Gregorian chants. Although Terence's plays often dealt with pagan material, the quality of his language promoted the copying and preserving of his text by the church. The preservation of Terence through the church enabled his work to influence much of later Western drama.[11]

Pietro Alighieri's Commentary to the Commedia states that his father took the title from Terence's plays and Giovanni Boccaccio copied out in his own hand all of Terence's Comedies and Apuleius' writings in manuscripts that are now in the Laurentian Library. Two of the earliest English comedies, Ralph Roister Doister and Gammer Gurton's Needle, are thought to parody Terence's plays. Montaigne, Shakespeare and Molière cite and imitate him.

Terence's plays were a standard part of the Latin curriculum of the neoclassical period. President of the United States John Adams once wrote to his son, "Terence is remarkable, for good morals, good taste, and good Latin... His language has simplicity and an elegance that make him proper to be accurately studied as a model."[12] American playwright Thornton Wilder based his novel The Woman of Andros on Terence's Andria.

Due to his cognomen Afer, Terence has long been identified with Africa and heralded as the first poet of the African diaspora by generations of writers, including Juan Latino, Phyllis Wheatley, Alexandre Dumas, Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou. Two of his plays were produced in Denver with Black actors.

Questions as to whether Terence received assistance in writing or was not the actual author have been debated over the ages, as described in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica:

[In a prologue to one of his plays, Terence] meets the charge of receiving assistance in the composition of his plays by claiming as a great honour the favour which he enjoyed with those who were the favorites of the Roman people. But the gossip, not discouraged by Terence, lived and throve; it crops up in Cicero and Quintilian, and the ascription of the plays to Scipio had the honour to be accepted by Montaigne and rejected by Diderot.[13]

See also

- Translation

- Metres of Roman comedy

- Codex Vaticanus 3868

- List of slaves

- Roman Africans

- Quod licet Iovi, non licet bovi

References

- More literally, "I am a human being; of that which is human, I think nothing estranged from me."

- Ricord, Frederick W. (1885). The Self-Tormentor (Heautontimorumenos) from the Latin of Publius Terentius Afer with More English Songs from Foreign Tongues. New York: Charles Scribner's. p. 25. Retrieved 22 January 2018 – via Internet Archive.. The quote appears in Act I, Scene 1, line 25, or at line 77 if the entire play is numbered continuously.

- Aeli Donati Commentum Terenti, accedunt Eugraphi Commentum et Scholia Bembina, ed. Paul Wessner, 3 Volumes, Leipzig, 1902, 1905, 1908.

- G. D' Anna, Sulla vita suetoniana di Terenzio, RIL, 1956, pp. 31-46, 89-90.

- Tenney Frank, "On Suetonius' Life of Terence." The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 54, No. 3 (1933), pp. 269-273.

- H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Latin Literature, 1954.

- Michael von Albrecht, Geschichte der römischen Literatur, Volume 1, Bern, 1992.

- "...the playwright Terence, who reached Rome as the slave of a senator in the second century BC, was a Berber", Suzan Raven, Rome in Africa, Routledge, 1993, p.122; ISBN 0-415-08150-5.

- Smith, William (editor); Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Lucanus, Terentius" Archived 2011-04-20 at the Wayback Machine, Boston, 1870.

- See, e.g., in Luther's Works: American Edition, vol. 40:317; 47:228.

- Holloway, Julia Bolton (1993). Sweet New Style: Brunetto Latino, Dante Alighieri, Geoffrey Chaucer, Essays, 1981-2005. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- John Adams by David McCullough, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, New York, 2001. Pg 259. ISBN 978-0-684-81363-9

-

Further reading

- Augoustakis, A. and Ariana Traill eds. (2013). A Companion to Terence. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. Malden/Oxford/Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Boyle, A. J., ed. (2004). Special Issue: Rethinking Terence. Ramus 33:1–2.

- Büchner, K. (1974). Das Theater des Terenz. Heidelberg: C. Winter.

- Davis, J. E. (2014). Terence Interrupted: Literary Biography and the Reception of the Terentian Canon. American Journal of Philology 135(3), 387–409.

- Forehand, W. E. (1985). Terence. Boston: Twayne.

- Goldberg, S. M. (1986). Understanding Terence. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Karakasis, E. (2005). Terence and the Language of Roman Comedy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Papaioannou, S., ed. (2014). Terence and Interpretation. Pierides, 4. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Pezzini, G. (2015). Terence and the Verb ‘To Be’ in Latin. Oxford Classical Monographs. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sharrock, A. (2009). Reading Roman Comedy: Poetics and Playfulness in Plautus and Terence. W.B. Stanford Memorial Lectures. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Library resources about Terence |

| By Terence |

|---|

- The six plays of Terence at The Latin Library (in Latin).

- Works by Terence at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Terence at Internet Archive

- At Perseus Digital Library:

- 15th-century scripts from Hecyra and Eunuchus, Center for Digital Initiatives, University of Vermont Libraries.

- Lewis E 196 Comediae at OPenn

- Terence's works: text, concordances and frequency list (in Latin).

- The Life of Terence, part of Suetonius's De Viris Illustribus, translated by John C. Rolfe.

- P. Terenti comoediae cum scholi Aeli Donati et Eugraphi commentariis, Reinhold Klotz (ed.), Lipsiae, sumptum fecitE. B. Schwickert, 1838, vol. 1, vol. 2.

- SORGLL: Terence, Eunuch 232-264, read in Latin by Matthew Dillon.

- Latin with Laughter: Terence through Time.