2020 Pacific hurricane season

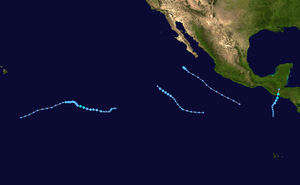

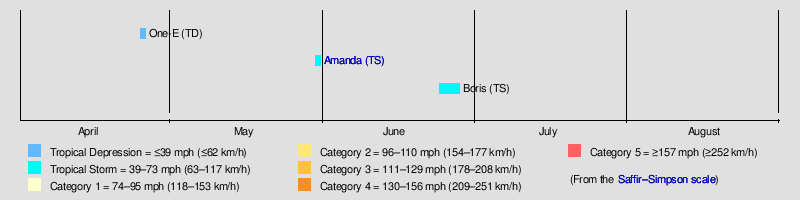

The 2020 Pacific hurricane season is an ongoing event in the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation, in which tropical cyclones form in the eastern Pacific Ocean. The season featured the earliest start to the season east of 140°W on record, surpassing Tropical Storm Adrian in 2017. The season officially began on May 15 in the East Pacific Ocean, and on June 1 in the Central Pacific; they will both end on November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Pacific basin. However, the formation of tropical cyclones is possible at any time of the year, as shown by the formation of Tropical Depression One-E on April 25. The formation of One-E resulted in the earliest start to a season in the Eastern Pacific since reliable records began in 1966.

| 2020 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | April 25, 2020 (record earliest in East Pacific) |

| Last system dissipated | Season ongoing |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Amanda |

| • Maximum winds | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 1003 mbar (hPa; 29.62 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 3 |

| Total storms | 2 |

| Hurricanes | 0 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 0 |

| Total fatalities | 33 total |

| Total damage | ≥ $200 million (2020 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The season's first named storm, Amanda, developed near Central America and struck Guatemala, causing widespread damage in neighboring El Salvador and killing 33 people amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Seasonal forecasts

| Record | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average (1981–2010): | 15.4 | 7.6 | 3.2 | [1] | |

| Record high activity: | 1992: 27 | 2015: 16 | 2015: 11 | [2] | |

| Record low activity: | 2010: 8 | 2010: 3 | 2003: 0 | [2] | |

| Date | Source | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| May 20, 2020 | SMN | 15–18 | 8–10 | 4–5 | [3] |

| May 21, 2020 | NOAA | 11–18 | 5–10 | 1–5 | [4] |

| Area | Named storms | Hurricanes | Major hurricanes | Ref | |

| Actual activity: | EPAC | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | CPAC | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Actual activity: | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

On May 20, 2020, the Servicio Meteorológico Nacional (SMN) issued its forecast for the season, predicting a total of 15–18 named storms, 8–10 hurricanes, and 4–5 major hurricanes to develop.[3] The next day, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) issued their outlook, calling for a below-normal to near-normal season with 11–18 named storms, 5–10 hurricanes, 1–5 major hurricanes, and an Accumulated Cyclone Energy index of 60% to 135% of the median. Factors they expected to reduce activity were near- or below-average sea surface temperatures across the eastern Pacific and the El Niño–Southern Oscillation remaining in the neutral phase, with the possibility of a La Niña developing.[4]

Seasonal summary

The Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the 2020 Pacific hurricane season, as of 03:00 UTC June 27, is 0.49 units (0.49 units from the Eastern Pacific and 0 units from the Central Pacific).[nb 1] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h).

Although hurricane season in the eastern Pacific does not officially begin until May 15, and on June 1 in the central Pacific,[5] activity this year began several weeks prior with the formation of the first tropical depression on April 25. This marked the earliest formation of a tropical cyclone in the basin, surpassing 2017's Tropical Storm Adrian.[6]

Systems

Tropical Depression One-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | April 25 – April 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min) 1006 mbar (hPa) |

On April 23, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) issued a Special Tropical Weather Outlook (STWO) for a broad area of low pressure located several hundred miles south of the tip of the Baja California Peninsula for potential development into a tropical cyclone.[7] Subsequently, the trough began to quickly organize with convection appearing to wrap around the elongated center of circulation. The low, supported by excellent outflow on its northern side, developed slowly throughout the day and into April 24 as it broke away from the Intertropical Convergence Zone, therefore the NHC assigned it a high possibility of formation in the next 48 hours on the following day due to these increases in organization.[8] However, by later April 24, shower and thunderstorm activity near the center began to diminish, yet the center became slightly more rounded.[9] On April 25, soon indicated by an ASCAT pass, the low developed a much more well-defined center overnight and new thunderstorms began to fully obscure the circulation. Around this time, the NHC upgraded the system to Tropical Depression One-E around 15:00 UTC on April 25, marking the earliest formation of a tropical cyclone in the basin to the east of the 140°W longitude since reliable records began in 1966, with the storm forming over three weeks early from the official start of the season.[10][6] The previous record for earliest forming storm was held by Tropical Storm Adrian of 2017, which formed on May 9.[10]

The depression drifted northwestwards after its formation, with much of its convection displaced to the south of the center as a result of increasing dry air surrounding the system.[11] However, a small convective burst allowed the depression to continue retaining its intensity despite dry air beginning to wrap into the circulation.[10] By April 26, dry air, increasing wind shear and cooling sea surface temperatures began to finally overthrow the small cyclone and deep convection near the center quickly began to dissipate leaving an exposed, ill-defined center displaced from what little thunderstorms remained, barely fitting the criteria for a tropical cyclone altogether.[12] The depression was declared to have dissipated and become a poorly defined remnant low by later that same day, due to a struggle to re-develop convection and increasingly stable air surrounding the center.[13] The next day, the remnant low fully dissipated.

Tropical Storm Amanda

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | May 30 – May 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1003 mbar (hPa) |

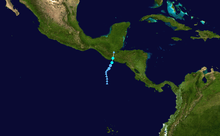

On May 24, the NHC first discussed the probability of possible tropical cyclogenesis associated with a broad area of low pressure that was forecast to form off the coast of El Salvador within a crossing tropical wave in the Atlantic Ocean.[14] The tropical wave tracked generally westward across the Caribbean Sea for several days, crossing over Panama, and entered the Eastern Pacific basin on May 26.[15] At this point, the NHC considered the disturbance to have a high chance of formation in several days.[15] Low pressure developed within the disturbance a day later, and a broad cyclonic circulation also began to develop as the wave was being enhanced by a Central American gyre on May 27.[16] Remaining nearly stationary for several days, the disturbance slowly developed as its circulation grew more well defined.

By May 30, the system developed central deep convection over a now closed low-level circulation and was considered sufficiently organized enough to be designated as Tropical Depression Two-E later that same day, remaining embedded within the eastern side of a Central American gyre.[17] The depression slowly intensified to a strength of 30 kt (35 mph, 55 km/h) in aid of fairly warm sea surface temperatures,[18] and at the time was considered unlikely to intensify further.[18] However, convective organization continued to improve as the system also became much more compact, and satellite estimates allowed the NHC to upgrade the tropical depression to Tropical Storm Amanda at 09:00 UTC on May 31, the first named storm of the season.[19] Only 3 hours after being named, at 12:00 UTC, Amanda made landfall in southeastern Guatemala and began to spread heavy rain inland.[20] Amanda rapidly weakened and dissipated over the country later that day while its mid-level circulation continued north, eventually regenerating as Tropical Storm Cristobal once it emerged over the Bay of Campeche on June 1.

In El Salvador, torrential rainfall caused significant damage along coastal cities in the country as rivers overflowed and swept away buildings.[21] Amanda killed 14 people in El Salvador,[22] of which at least six died due to flash flooding, and one died from a collapsed home.[23] More than 900 homes were damaged across the country and 1,200 families were evacuated to 51 shelters across La Libertad, San Salvador, Sonsonate, and San Vicente. In the capital, San Salvador, 50 houses were destroyed and 23 vehicles fell into a sinkhole.[24][25] El Salvador President Nayib Bukele declared a 15-day national state of emergency due to the storm.[23] Movement restrictions in place for the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic were temporarily lifted to allow people to purchase medicines, while hardware stores were allowed to open with limited capacity so people could purchase equipment for repairs.[24]

Tropical Storm Boris

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 24 – June 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min) 1005 mbar (hPa) |

On June 20, the NHC began monitoring a small area of thunderstorms associated with an small low pressure area within the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[26] The system gradually organized and intensified over the next few days and a tight circulation began to emerge from the disorganized thunderstorms surrounding the area on June 23. On the next day, the tight circulation became more well-defined and a circular region of thunderstorms began to develop south of the exposed center. Thus, the NHC initiated advisories on the system, designating it Tropical Depression Three-E.[27] The depression gradually tracked west-northwestward for the rest of the day with little change in strength due to an onset of dry air being drawn into the circulation.[28] This dry air also caused a significant waning of the system's thunderstorm activity, leaving the center of circulation mostly exposed.[28] By the next day, the depression had changed very little in intensity but deep convection began to sporadically appear near the center while the storm continued to struggle against dry air and increasingly stable conditions.[29] Despite being poorly organized, a pass from ASCAT indicated the storm was producing 35 kt winds relatively far from the center and convective activity became more compact and as a result the depression was upgraded to tropical storm intensity and provided the name Boris at around 21:00 UTC on June 25.[30] However, unfavorable conditions continued to slowly degrade the storm's new central convection over time,[31] and Boris weakened back down to a tropical depression at 9:00 UTC on June 26, just 12 hours after becoming a tropical storm, as overall organization of the system became poor due to an entrainment of dry air, moderate wind shear, and decreasing sea surface temperatures.[32]

By 21:00 UTC June 26, a degenerating Boris crossed 140°W and entered the Central Pacific basin as a tropical depression, becoming the first June tropical cyclone in the basin since Tropical Storm Barbara in 2001 and only the second ever recorded, dating back to 1966.[33] Boris continued to crawl west through an increasingly hostile environment into June 27, leaving the center almost completely exposed and only small patches of convection remaining near the LLC.[34] As the system continued to rapidly lose thunderstorm activity, the system was downgraded to a remnant low by early on June 28 and thus the last advisory was issued by the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.[35]

Storm names

The following names will be used for named storms that form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean during 2020. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization during the joint 42nd and 43rd Sessions of the RA IV Hurricane Committee in the spring of 2021 (in concurrence with any names from the 2019 season). The names not retired from this list will be used again in the 2026 season.[36] This is the same list used in the 2014 season, with the exception of the name Odalys, which replaced Odile.

|

|

|

For storms that form in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's area of responsibility, encompassing the area between 140 degrees west and the International Date Line, all names are used in a series of four rotating lists.[37] The next four names that will be slated for use in 2020 are shown below.

|

|

|

|

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms and that have formed in the 2020 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a tropical wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 2020 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-E | April 25 – 26 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Amanda | May 30 – 31 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1003 | Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Belize, Costa Rica, Southern Mexico, Yucatan Peninsula | ≥200 million | 33 | |||

| Boris | June 24 – 28 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 3 systems | April 25 – Present | 40 (65) | 1003 | ≥200 million | 33 | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 2020

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of Pacific hurricane seasons

- 2020 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2020 Pacific typhoon season

- 2020 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2019–20, 2020–21

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2019–20, 2020–21

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2019–20, 2020–21

Notes

- The totals represent the sum of the squares for every (sub)tropical storm's intensity of over 33 knots (38 mph, 61 km/h), divided by 10,000. Calculations are provided at Talk:2020 Pacific hurricane season/ACE calcs.

References

- "Background Information: East Pacific Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. College Park, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 22, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2014.

- National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center. "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2019". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

- "Pronóstico de Ciclones Tropicales 2020". smn.cna.gob.mx.

- "NOAA 2020 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Outlook". Climate Prediction Center. May 21, 2020. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- Dorst Neal. When is hurricane season? (Report). Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.

- Mersereau, Dennis (April 25, 2020). "The Eastern Pacific Ocean Just Saw Its Earliest Tropical Cyclone On Record". Forbes. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- Andrew Latto; Daniel Brown (April 25, 2020). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Andrew Latto (April 25, 2020). "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Latto, Andrew. "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-25.

- David Zelinsky (April 25, 2020). "Tropical Depression ONE-E". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- Cangialosi, John. "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Number 3". National Hurricane Center.

- Stewart, Stacy. "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center.

- Stewart, Stacy. "Post-Tropical Cyclone One-E Discussion Number 6". National Hurricane Center.

- "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive May 24, 2020". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive May 26, 2020". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- NHC_TAFB (2020-05-30). "May 30 10AM: A Central American Gyre over the eastern Pacific and northern Central America is producing large clusters of thunderstorms. These thunderstorms will continue to occur over Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Belize, and southeastern Mexico thru next week (1/2)pic.twitter.com/biwz3Ka9fc". @NHC_TAFB. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Cangialosi, John. "Tropical Depression TWO-E Forecast Discussion Number 1". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Beven, Jack. "Tropical Depression TWO-E Forecast Discussion 2". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Stewart, Stacy. "Tropical Storm AMANDA Forecast Discussion Number 3". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "Tropical Storm AMANDA Intermediate Advisory Number 3A". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "La tormenta tropical Amanda provoca inundaciones y el desbordamiento de ríos en El Salvador". Noticias de El Salvador - elsalvador.com (in Spanish). 2020-05-31. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "More than a dozen people killed after tropical storm Amanda lashes El Salvador, Guatemala". France 24. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Alerta Roja por lluvias: Tormenta tropical Amanda deja al menos siete fallecidos y severas inundaciones en El Salvador". Noticias de El Salvador - La Prensa Gráfica | Informate con la verdad (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "Hurricane Amanda kills 14 people in El Salvador". Seven News. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "Deadly Tropical Storm Amanda hits El Salvador, Guatemala". Channel NewsAsia. Agence France-Presse. June 1, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- "NHC Graphical Outlook Archive". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- "Tropical Depression THREE-E". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- "Tropical Depression THREE-E Forecast Discussion 4". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "Tropical Depression THREE-E Forecast Discussion 5". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "Tropical Storm Boris Forecast Discussion Number 6". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-25.

- "Tropical Storm BORIS Forecast Discussion Number 7". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- "Tropical Depression BORIS Forecast Discussion Number 8". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- "Tropical Depression BORIS Forecast Discussion 12". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- "Tropical Depression BORIS Forecast Discussion 13". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-27.

- "Post-Tropical Cyclone Boris Forecast Discussion Number 15". www.nhc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- "Tropical Cyclone Names". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013-04-11. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- "Pacific Tropical Cyclone Names 2016-2021". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 12, 2016. Archived from the original (PHP) on December 30, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 2020 Pacific hurricane season. |