İdil

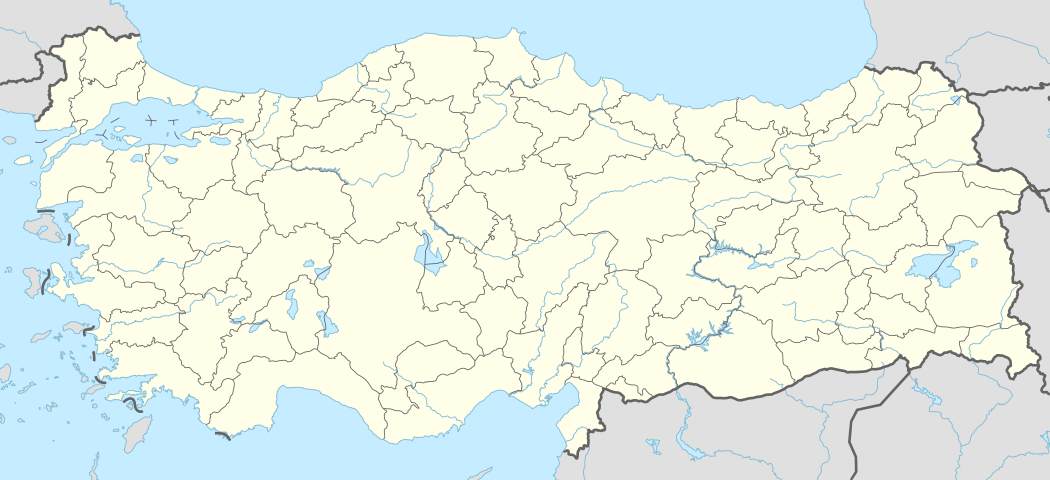

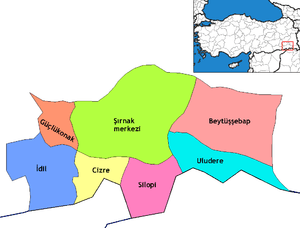

İdil (Classical Syriac: ܐܙܟ, romanized: Azakh,[3][nb 1] or Beth Zabday,[5] Kurdish: Hezex,[6] Arabic: آزخ, romanized: Azekh)[7] is a town and district in Şırnak Province in southeastern Turkey. It is located in the historical region of Tur Abdin.

İdil | |

|---|---|

İdil | |

| Coordinates: 37°20′30″N 41°53′30″E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Şırnak |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Songül Erdem (HDP) |

| • Kaymakam | Zafer Sağ |

| Area | |

| • District | 1,266.10 km2 (488.84 sq mi) |

| Population (2012)[2] | |

| • Urban | 24,595 |

| • District | 71,147 |

| • District density | 56/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| Post code | 733xx |

| Website | www.idil.bel.tr |

In the town, there is a Syriac Orthodox Church of the Mother of God (Turkish: Meryem Ana Kilisesi).[8]

History

Azakh is identified as the town of Ashikhu,[9] or Asiḫu, which is earliest attested in an administrative note from the governor's archive at Tell Halaf, during the reign of Adad-nirari III, King of Assyria, in the late 9th and early 8th century BC.[10] Azakh was later conflated with the neighbouring city of Bezabde, and led to the town's alternative Syriac name Beth Zabday.[11]

At the beginning of the 20th century, the town had a population of 1000, and was inhabited by Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Catholic Christians.[12] Assyrians emigrated from Azakh to Brazil in 1914 and again in 1925,[13] at which time 100 Assyrians were deported from Azakh.[14]

Amidst the Assyrian genocide, in July 1915,[12] refugees from the villages of Esfes, Kefshenne, Kufakh, Babqqa, and Khaddel fled to Azakh.[15] The town was subsequently attacked by Kurdish tribesmen from mid-August until their withdrawal on 9 September.[12] An expeditionary force of approximately 8000 Ottoman soldiers and Kurdish auxiliaries,[16] led jointly by Max Erwin von Scheubner-Richter and Ömer Naci, was diverted from its original task to conduct anti-Russian operations in Iran to besiege Azakh,[17] and arrived in late October.[12] Scheubner-Richter refused to involve Germans in the siege, and the first attack began on 7 November.[12] After subsequent attacks, and an Assyrian counter-attack on 14 November, the Turkish army retreated on 21 November.[12]

The town became the seat of a bucak (subdistrict) of Cizre in 1924.[18] 257 Syriac Orthodox men from Azakh and neighbouring villages were imprisoned by the Turkish government in 1926 initially at Cizre, and later at Midyat.[19] Assyrians from Azakh emigrated to Ain Duwar and Al-Malikiyah in northeastern Syria in the early 1930s after the construction of French military bases.[20] The town was elevated to district in 1937, upon which it was officially renamed İdil.[18] The town was inhabited by 3500 Assyrians in 1964.[21] As a result of the Cypriot crisis of 1963-1964, Assyrians of Azakh were the victim of anti-Christian riots.[22] The town was exclusively populated by Christians until the mid-1970s;[23] this was in part due to the prohibition of sale of property to Muslim Kurds by Mayor Şükrü Tutuş.[24]

Efforts to encroach on the Assyrian population resulted in the construction of social housing for Kurds in the town, who consequently amounted to 10% of the population,[24] and the election of Abdurrahman Abay, chief of the Kurdish Kecan tribe, as mayor in 1979 with the aid of the Turkish authorities, including the military commander, judge, and district governor.[25] Abay alleged that he received congratulations via telegram from Anwar Sadat, President of Egypt, for the "Muslim conquest of Idil".[25] This led the Assyrian population to decline in the 1970s and 1980s.[21]

After their forced eviction by the Turkish army on 20 November 1993, a number of Assyrian refugees from Hassana fled to Azakh.[26] On 9 January 1994, Melke Tok, priest of Miden, was abducted whilst en route from Azakh to Bsorino.[27] The priest was later released after negotiations,[28] and attested that, whilst in captivity, he was buried alive and pressured into converting to Islam.[29] The murder of former mayor Şükrü Tutuş on 17 June 1994 led the remaining Christian population of several hundred people to seek asylum in Western Europe, and was followed by the Kurdish repopulation of the town.[25] Assyrians later returned, but by 2015 only 50 Assyrians inhabited the town.[21]

The eruption of violence in early 2016 led all but two Assyrians to flee Azakh,[21] as well as an estimated three thousand people, and a curfew was imposed on 16 February.[30] The Turkish army began operations in the town on 18 February and claimed to have killed at least 47 PKK militants by 25 February.[31] The curfew was partially lifted on 31 March and the refugees returned to Azakh,[32] including at least four Assyrian families.[21] In late July 2019, Assyrian properties in the district were struck by suspected arson attacks.[33]

Notable people

- Jacques Behnan Hindo (b. 1941), Syriac Catholic Archbishop of Al-Hasakah-Nisibis

Mayors

| Election | Mayor | Party |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Songül Erdem | HDP |

| 2014 | Mehmet Muhdi Arslan | BDP |

| 2009 | Resul Sadak | DTP |

| 2004 | Resul Sadak | SHP |

| 1994 | Murat Dalmış | DYP |

| 1979 | Abdurrahman Abay | ANAP |

| 1966 | Şükrü Tutuş | ANAP |

Mayor Mehmet Muhdi Arslan was suspended on 20 September 2016 following his arrest in August on suspicion of aiding and abetting the PKK, and Kaymakam (district governor) Ersin Tepeli was appointed as trustee on the following day.[34]

References

Notes

- Alternatively transliterated as Hazakh or Azekh.[4]

Citations

- "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- Āzakh. The Syriac Gazeteer.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 351

- Biner (2019), p. x

- Avcıkıran (2009), p. 57

- "السريان يشاركون في مؤتمر بازبدي (آزخ) الدولي في تركيا". Ishtar TV (in Arabic). Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- DelCogliano (2006), p. 341

- Palmer (1990), p. 29

- Radner (2006), pp. 296-297

- Palmer (1990), p. 155

- Azakh. Foundation for Conservation and Promotion of the Aramaic Cultural Heritage. (in German)

- Atto (2011), p. 163

- Atto (2011), p. 98

- Sato (2001), p. 54

- DelCogliano (2006), p. 342

- Dadrian (2002), p. 66

- İdil. Şırnak Valiliği (in Turkish).

- Sato (2001), p. 63

- Sato (2001), p. 64

- Güsten (2016), p. 9

- Güsten (2016), p. 8

- Joseph (1984), p. 103

- Susanne Güsten (22 January 2015). "Robert Tutus ist der letzte Christ im anatolischen Idil". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Susanne Güsten (4 April 2012). "Hopes to Revive the Christian Area of Turkey". New York Times. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Atto (2011), p. 139

- "UA 03/94 - TURKEY: ABDUCTION / FEAR OF EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLING: MELKE TOK". Amnesty International. 10 January 1994. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Atto (2011), p. 133

- Pacal, Jan (29 August 1996). "What happened to the Turkish Assyrians?". Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Fresh curfew declared amid exodus from İdil". Hürriyet Daily News. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Turkish army kills 47 PKK militants in İdil in week". Hürriyet Daily News. 25 February 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Thousands return to ruined İdil after 43-day curfew". Hürriyet Daily News. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Fires on Assyrian land raise arson alarm". Ahval News. 6 August 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "İdil Belediyesi'ne kayyum atandı". Sabah (in Turkish). 21 September 2016. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

Bibliography

- Atto, Naures (2011). Hostages in the Homeland, Orphans in the Diaspora: Identity Discourses Among the Assyrian/Syriac Elites in the European Diaspora (PDF). Leiden University Press. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Avcıkıran, Adem (2009). Kürtçe Anamnez Anamneza bi Kurmancî (PDF) (in Turkish and Kurdish). Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N. (2002). "The Armenian Question and the Wartime Fate of the Armenians as Documented by the Officials of the Ottoman Empire's World War I Allies: Germany and Austria-Hungary". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 34 (1): 59–85. doi:10.1017/S0020743802001034.

- DelCogliano, Mark (2006). "Syriac Monasticism in Tur Abdin: A Present-Day Account". Cistercian Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 311–349.

- Güsten, Susanne (2016). A Farewell to Tur Abdin (PDF). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Joseph, John (1984). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacobites in an Age of Transition. SUNY Press.

- Palmer, Andrew (1990). Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur Abdin. Cambridge University Press.

- Radner, Karen (2006). "How to reach the Upper Tigris: The route through the Tur Abdin". State Archives of Assyria Bulletin. 15: 273–305.

- Sato, Noriko (2001). Memory and Social Identity among Syrian Orthodox Christians (PDF). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press. ISBN 9780907132349.