Resonant trans-Neptunian object

|

|

‡ Trans-Neptunian dwarf planets are called "plutoids" |

In astronomy, a resonant trans-Neptunian object is a trans-Neptunian object (TNO) in mean-motion orbital resonance with Neptune. The orbital periods of the resonant objects are in a simple integer relations with the period of Neptune e.g. 1:2, 2:3 etc. Resonant TNOs can be either part of the main Kuiper belt population, or the more distant scattered disc population.[1]

Distribution

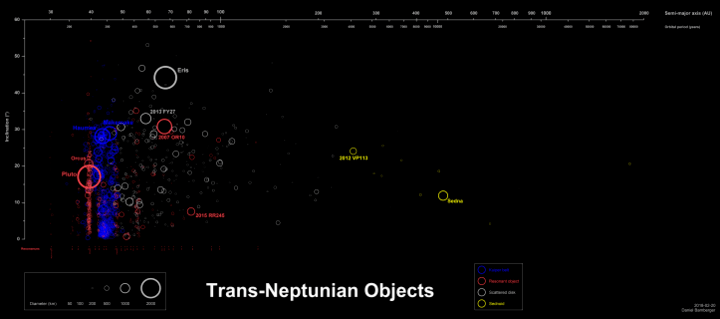

The diagram illustrates the distribution of the known trans-Neptunian objects. Resonant objects are plotted in red. Orbital resonances with Neptune are marked with vertical bars; 1:1 marks the position of Neptune’s orbit and its trojans, 2:3 marks the orbit of Pluto and plutinos, and 1:2, 2:5 etc. mark a number of smaller families.

The designation 2:3 or 3:2 both refer to the same resonance for TNOs. There is no ambiguity, because TNOs have, by definition, periods longer than Neptune. The usage depends on the author and the field of research.

Origin

Detailed analytical and numerical studies of Neptune’s resonances have shown that the objects must have a relatively precise range of energies.[2][3] If the object's semi-major axis is outside these narrow ranges, the orbit becomes chaotic, with widely changing orbital elements.

As TNOs were discovered, more than 10% were found to be in 2:3 resonances, far from a random distribution. It is now believed that the objects have been collected from wider distances by sweeping resonances during the migration of Neptune.[4]

Well before the discovery of the first TNO, it was suggested that interaction between giant planets and a massive disk of small particles would, via angular-momentum transfer, make Jupiter migrate inwards and make Saturn, Uranus, and especially Neptune migrate outwards. During this relatively short period of time, Neptune's resonances would be sweeping the space, trapping objects on initially varying heliocentric orbits into resonance.[5]

Known populations

2:3 resonance ("plutinos", period ~250 years)

The 2:3 resonance at 39.4 AU is by far the dominant category among the resonant objects, with 248 confirmed and 84 possible member bodies (as of February 2018).[6] The objects following orbits in this resonance are named plutinos after Pluto, the first such body discovered. Large, numbered plutinos include:[6]

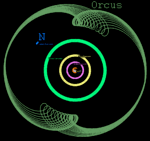

- 90482 Orcus

- (208996) 2003 AZ84

- (455502) 2003 UZ413

- (84922) 2003 VS2

- 28978 Ixion

- (84719) 2002 VR128

- (469372) 2001 QF298

- 38628 Huya

- (33340) 1998 VG44

- (15789) 1993 SC

- (444745) 2007 JF43

- (469421) 2001 XD255

- (120216) 2004 EW95

- 47171 Lempo

- (504555) 2008 SO266

- (307463) 2002 VU130

- (55638) 2002 VE95

- (450265) 2003 WU172

- (469987) 2006 HJ123

- (508823) 2001 RX143

- (469704) 2005 EZ296

3:5 resonance (period ~275 years)

A population of 36 objects at 42.3 AU as of February 2018, the following of which have been numbered:[6]

- (126154) 2001 YH140

- (470523) 2008 CS190

- (149349) 2002 VA131

- (469584) 2003 YW179

- (469420) 2001 XP254

- (434709) 2006 CJ69

- (15809) 1994 JS

- (503883) 2001 QF331

- (143751) 2003 US292

4:7 resonance (period ~290 years)

Another important population of objects (27 identified as of February 2018) is orbiting the Sun at 43.7 AU (in the midst of the classical objects). The objects are rather small (with two exceptions, H>6) and most of them follow orbits close to the ecliptic. Objects with well established orbits include:[6]

- 2014 TZ85, the largest

- 2015 BP518

- (119956) 2002 PA149

- (119066) 2001 KJ76

- (135024) 2001 KO76

- (119070) 2001 KP77

- (181871) 1999 CO153

- 385446 Manwë

- (118378) 1999 HT11

- (385527) 2004 OK14

- (500828) 2013 GR136

- (118698) 2000 OY51

1:2 resonance ("twotinos", period ~330 years)

This resonance at 47.8 AU is often considered to be the outer edge of the Kuiper belt, and the objects in this resonance are sometimes referred to as twotinos. Twotinos have inclinations less than 15 degrees and generally moderate eccentricities (0.1 < e < 0.3).[7] An unknown number of the 2:1 resonants likely did not originate in a planetesimal disk that was swept by the resonance during Neptune's migration, but were captured when they had already been scattered.[8]

There are far fewer objects in this resonance (a known total of 50 as of February 2018) than plutinos. Long-term orbital integration shows that the 1:2 resonance is less stable than 2:3 resonance; only 15% of the objects in 1:2 resonance were found to survive 4 Gyr as compared with 28% of the plutinos.[7] Consequently, it might be that twotinos were originally as numerous as plutinos, but their population has dropped significantly below that of plutinos since.[7]

Objects with well established orbits include (in order of the absolute magnitude):[6]

- (119979) 2002 WC19

- (308379) 2005 RS43

- (312645) 2010 EP65

- (26308) 1998 SM165

- (469505) 2003 FE128

- (495189) 2012 VR113

- (137295) 1999 RB216

- (500880) 2013 JJ64

- (20161) 1996 TR66

- (470083) 2006 SG369

- (130391) 2000 JG81

- (500877) 2013 JE64

2:5 resonance (period ~410 years)

Objects with well established orbits at 55.4 AU include:[6]

- (84522) 2002 TC302, a dwarf planet candidate

- (495603) 2015 AM281

- (26375) 1999 DE9

- (143707) 2003 UY117

- (471172) 2010 JC80

- (471151) 2010 FD49

- (472235) 2014 GE45

- (119068) 2001 KC77

- (60621) 2000 FE8

- (38084) 1999 HB12

- (135571) 2002 GG32

- (69988) 1998 WA31

In total, the orbits of 40 objects are classified as 2:5 as of February 2018.

Other resonances

So called higher-order resonances are known for a limited number of objects, including[6]

- 4:5 (35 AU, ~205 years) (432949) 2012 HH2, (127871) 2003 FC128, (308460) 2005 SC278, (79969) 1999 CP133, (427581) 2003 QB92, (131697) 2001 XH255

- 3:4 (36.5 AU, ~220 years) (143685) 2003 SS317, (15836) 1995 DA2

- 5:8 (41 AU, ~264 years) 2014 GA54, 2005 VZ122

- 5:9 (44.5 AU, ~295 years) (437915) 2002 GD32

- 6:11 (45 AU, ~303 years) 2014 MC70, (182294) 2001 KU76, (505477) 2013 UM15, 2010 LQ68

- 9:19 (50 AU, ~349 years) 2003 QX113

- 4:9 (52 AU, ~370 years) (42301) 2001 UR163, (182397) 2001 QW297

- 3:7 (53 AU, ~385 years) (495297) 2013 TJ159, (181867) 1999 CV118, (131696) 2001 XT254, (95625) 2002 GX32, (183964) 2004 DJ71, (500882) 2013 JN64

- 5:12 (54 AU, ~395 years) (79978) 1999 CC158, (119878) 2001 CY224

- 3:8 (57 AU, ~440 years) (82075) 2000 YW134

- 4:13 (66 AU, ~537 years) 2009 DJ143

- 3:10 (67 AU, ~549 years) (225088) 2007 OR10

- 2:7 (70 AU, ~580 years) (471143) 2010 EK139, (160148) 2001 KV76

- 3:11 (72 AU, ~606 years) 2014 UV224, 2013 AR183

- 21:5 (78 AU, ~706 years) 2010 JO179[9]

- 2:9 (80 AU, ~730 years) 2015 RR245, 2003 UA414

- 2:11 (94 AU, ~909 years) 2005 RP43, 2011 HO60

A few objects are known on simple, distant resonances:[6]

- 1:3 (62.5 AU, ~495 years) (385607) 2005 EO297, (136120) 2003 LG7

- 1:4 (76 AU, ~660 years) 2003 LA7

- 1:5 (88 AU, ~825 years) 2003 YQ179, 2007 FN51, 2007 LF38[10]

- 1:6 (99 AU, ~1000 years) 2011 WJ157

- 1:9 (129 AU, ~1500 years) two known objects: 2015 KE172 and 2007 TC434.[11]

A notable unproven dwarf planet resonance is

1:1 resonance (Neptune trojans, period ~165 years)

A few objects have been discovered following orbits with semi-major axes similar to that of Neptune, near the Sun–Neptune Lagrangian points. These Neptune trojans, termed by analogy to the (Jupiter) Trojan asteroids, are in 1:1 resonance with Neptune. 17 are known as of February 2018,[6] and include the following objects:

- 2013 KY18

- (316179) 2010 EN65

- 2011 WG157

- 2006 RJ103

- 2011 SO277

- 2001 QR322

- 2010 TT191

- 2007 VL305

- 2011 HM102

- 2008 LC18

- (385695) 2005 TO74

- 2014 QO441

- 385571 Otrera

- 2004 KV18

- 2005 TN53

- 2012 UV177

- 2014 QP441

Only 4 objects are near Neptune's L5 Lagrangian point; the others are located in Neptune's L4 region.[13] (316179) 2010 EN65 is a so-called "jumping trojan", currently transitioning from librating around L4 to librating around L5, via the L3 region.[14]

Coincidental versus true resonances

One of the concerns is that weak resonances may exist and would be difficult to prove due to the current lack of accuracy in the orbits of these distant objects. Many objects have orbital periods of more than 300 years and most have only been observed over a short observation arc of a couple years. Due to their great distance and slow movement against background stars, it may be decades before many of these distant orbits are determined well enough to confidently confirm whether a resonance is true or merely coincidental. A true resonance will smoothly oscillate while a coincidental near resonance will circulate. (See Toward a formal definition)

Simulations by Emel’yanenko and Kiseleva in 2007 show that (131696) 2001 XT254 is librating in a 3:7 resonance with Neptune.[15] This libration can be stable for less than 100 million to billions of years.[15]

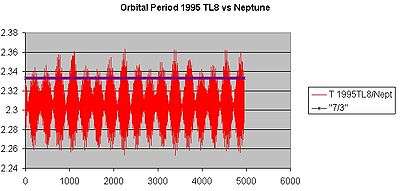

Emel’yanenko and Kiseleva also show that (48639) 1995 TL8 appears to have less than a 1% probability of being in a 3:7 resonance with Neptune, but it does execute circulations near this resonance.[15]

Toward a formal definition

The classes of TNO have no universally agreed precise definitions, the boundaries are often unclear and the notion of resonance is not defined precisely. The Deep Ecliptic Survey introduced formally defined dynamical classes based on long-term forward integration of orbits under the combined perturbations from all four giant planets. (see also formal definition of classical KBO)

In general, the mean-motion resonance may involve not only orbital periods of the form

where p and q are small integers, λ and λN are respectively the mean longitudes of the object and Neptune, but can also involve the longitude of the perihelion and the longitudes of the nodes (see orbital resonance, for elementary examples)

An object is resonant if for some small integers (p,q,n,m,r,s), the argument (angle) defined below is librating (i.e. is bounded):[16]

where the are the longitudes of perihelia and the are the longitudes of the ascending nodes, for Neptune (with subscripts "N") and the resonant object (no subscripts).

The term libration denotes here periodic oscillation of the angle around some value and is opposed to circulation where the angle can take all values from 0 to 360°. For example, in the case of Pluto, the resonant angle librates around 180° with an amplitude of around 82° degrees, i.e. the angle changes periodically from 180°−82° to 180°+82°.

All new plutinos discovered during the Deep Ecliptic Survey proved to be of the type

similar to Pluto's mean-motion resonance.

More generally, this 2:3 resonance is an example of the resonances p:(p+1) (for example 1:2, 2:3, 3:4) that have proved to lead to stable orbits.[4] Their resonant angle is

In this case, the importance of the resonant angle can be understood by noting that when the object is at perihelion, i.e. , then

i.e. gives a measure of the distance of the object's perihelion from Neptune.[4] The object is protected from the perturbation by keeping its perihelion far from Neptune provided librates around an angle far from 0°.

Classification methods

As the orbital elements are known with a limited precision, the uncertainties may lead to false positives (i.e. classification as resonant of an orbit which is not).

A recent approach[17] considers not only the current best-fit orbit but also two additional orbits corresponding to the uncertainties of the observational data. In simple terms, the algorithm determines whether the object would be still classified as resonant if its actual orbit differed from the best fit orbit, as the result of the errors in the observations.

The three orbits are numerically integrated over a period of 10 million years. If all three orbits remain resonant (i.e. the argument of the resonance is librating, see formal definition), the classification as a resonant object is considered secure.[17]

If only two out of the three orbits are librating the object is classified as probably in resonance. Finally, if only one orbit passes the test, the vicinity of the resonance is noted to encourage further observations to improve the data.[17]

The two extreme values of the semi-major axis used in the algorithm are determined to correspond to uncertainties of the data of at most 3 standard deviations. Such range of semi-axis values should, with a number of assumptions, reduce the probability that the actual orbit is beyond this range to less than 0.3%.

The method is applicable to objects with observations spanning at least 3 oppositions.[17]

References

- ↑ Hahn J. Malhotra R.Neptune's migration into a stirred-up Kuiper Belt The Astronomical Journal, 130, pp.2392-2414, Nov.2005.Full text on arXiv.

- ↑ Malhotra, Renu The Phase Space Structure Near Neptune Resonances in the Kuiper Belt. Astronomical Journal v.111, p.504 preprint

- ↑ E. I. Chiang and A. B. Jordan, On the Plutinos and Twotinos of the Kuiper Belt, The Astronomical Journal, 124 (2002), pp.3430–3444. (html)

- 1 2 3 Renu Malhotra, The Origin of Pluto's Orbit: Implications for the Solar System Beyond Neptune, The Astronomical Journal, 110 (1995), p. 420 Preprint.

- ↑ Malhotra, R.; Duncan, M. J.; Levison, H. F. Dynamics of the Kuiper Belt. Protostars and Planets IV, University of Arizona Press, p. 1231 preprint

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Johnston, Wm. Robert (30 December 2017). "List of Known Trans-Neptunian Objects". Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 M. Tiscareno; R. Malhotra (April 2008). "Chaotic Diffusion of Resonant Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 194 (3): 827–837. arXiv:0807.2835. Bibcode:2009AJ....138..827T. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/3/827.

- ↑ Lykawka, Patryk Sofia & Mukai, Tadashi (July 2007). "Dynamical classification of trans-neptunian objects: Probing their origin, evolution, and interrelation" (PDF). Icarus. 189 (1): 213–232. Bibcode:2007Icar..189..213L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.01.001.

- ↑ A Dwarf Planet Class Object in the 21:5 Resonance with Neptune

- ↑ Pike, R. E.; Kavelaars, J. J.; Petit, J. M.; Gladman, B. J.; Alexandersen, M.; Volk, K.; Shankman, C. J. (2015). "The 5:1 Neptune Resonance as Probed by CFEPS: Dynamics and Population". The Astronomical Journal. 149 (6): 202. arXiv:1504.08041. Bibcode:2015AJ....149..202P. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/149/6/202.

- ↑ Volk, Kathryn (15 February 2018). "OSSOS IX: two objects in Neptune's 9:1 resonance -- implications for resonance sticking in the scattering population". arXiv:1802.05805. Bibcode:2018AJ....155..260V. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aac268. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ↑ D. Ragozzine; M. E. Brown (2007-09-04). "Candidate Members and Age Estimate of the Family of Kuiper Belt Object 2003 EL61". The Astronomical Journal. 134 (6): 2160–2167. arXiv:0709.0328. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.2160R. doi:10.1086/522334.

- ↑ "List Of Neptune Trojans". Minor Planet Center. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ de la Fuente Marcos, C.; de la Fuente Marcos, R. (November 2012). "Four temporary Neptune co-orbitals: (148975) 2001 XA255, (310071) 2010 KR59, (316179) 2010 EN65, and 2012 GX17". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 547: 7. arXiv:1210.3466. Bibcode:2012A&A...547L...2D. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201220377. Retrieved 7 September 2016. (rotating frame)

- 1 2 3 Emel’yanenko, V. V; Kiseleva, E. L. (2008). "Resonant motion of trans-Neptunian objects in high-eccentricity orbits". Astronomy Letters. 34 (4): 271–279. Bibcode:2008AstL...34..271E. doi:10.1134/S1063773708040075.

- ↑ J. L. Elliot, S. D. Kern, K. B. Clancy, A. A. S. Gulbis, R. L. Millis, M. W. Buie, L. H. Wasserman, E. I. Chiang, A. B. Jordan, D. E. Trilling, and K. J. Meech The Deep Ecliptic Survey: A Search for Kuiper Belt Objects and Centaurs. II. Dynamical Classification, the Kuiper Belt Plane, and the Core Population. The Astronomical Journal, 129 (2006), pp. preprint Archived 2006-08-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4

B. Gladman, B. Marsden, C. VanLaerhoven (2008). "Nomenclature in the Outer Solar System". In The Solar System Beyond Neptune,

ISBN 9780816527557. templatestyles stripmarker in

|journal=at position 43 (help)

Further reading

- John K. Davies; Luis H. Barrera, eds. (2004-08-03). The First Decadal Review of the Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt. Springer. ISBN 1-4020-1781-2.

- E. I. Chiang; J. R. Lovering; R. L. Millis; M. W. Buie; L. H. Wasserman & K. J. Meech (June 2003). "Resonant and Secular Families of the Kuiper Belt". Earth, Moon, and Planets. Springer Netherlands. 92 (1&ndash, 4): 49–62. arXiv:astro-ph/0309250. Bibcode:2003EM&P...92...49C. doi:10.1023/B:MOON.0000031924.20073.d0.

- E. I. Chiang; A. B. Jordan; R. L. Millis; M. W. Buie; L. H. Wasserman; J. L. Elliot; S. D. Kern; D. E. Trilling; K. J. Meech & R. M. Wagner (2003-01-21). "Resonance occupation in the Kuiper Belt: case examples of the 5:2 and trojan resonances". The Astronomical Journal. The American Astronomical Society. 126 (1): 430–443. arXiv:astro-ph/0301458. Bibcode:2003AJ....126..430C. doi:10.1086/375207.

- Renu Malhotra. "The Kuiper Belt as a Debris Disk" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-10-22. (as HTML)