Nice model

The Nice (/ˈniːs/) model is a scenario for the dynamical evolution of the Solar System. It is named for the location of the Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, where it was initially developed, in 2005 in Nice, France.[1][2][3] It proposes the migration of the giant planets from an initial compact configuration into their present positions, long after the dissipation of the initial protoplanetary disk. In this way, it differs from earlier models of the Solar System's formation. This planetary migration is used in dynamical simulations of the Solar System to explain historical events including the Late Heavy Bombardment of the inner Solar System, the formation of the Oort cloud, and the existence of populations of small Solar System bodies including the Kuiper belt, the Neptune and Jupiter trojans, and the numerous resonant trans-Neptunian objects dominated by Neptune. Its success at reproducing many of the observed features of the Solar System means that it is widely accepted as the current most realistic model of the Solar System's early evolution,[3] although it is not universally favoured among planetary scientists. Later research revealed a number of differences between the original Nice model's predictions and observations of the current Solar System, for example the orbits of the terrestrial planets and the asteroids, leading to its modification.

Description

The original core of the Nice model is a triplet of papers published in the general science journal Nature in 2005 by an international collaboration of scientists: Rodney Gomes, Hal Levison, Alessandro Morbidelli, and Kleomenis Tsiganis.[4][5][6] In these publications, the four authors proposed that after the dissipation of the gas and dust of the primordial Solar System disk, the four giant planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune) were originally found on near-circular orbits between ~5.5 and ~17 astronomical units (AU), much more closely spaced and compact than in the present. A large, dense disk of small rock and ice planetesimals, their total about 35 Earth masses, extended from the orbit of the outermost giant planet to some 35 AU.

Scientists understand so little about the formation of Uranus and Neptune that Levison states, "...the possibilities concerning the formation of Uranus and Neptune are almost endless."[7] However, it is suggested that this planetary system evolved in the following manner. Planetesimals at the disk's inner edge occasionally pass through gravitational encounters with the outermost giant planet, which change the planetesimals' orbits. The planets scatter the majority of the small icy bodies that they encounter inward, exchanging angular momentum with the scattered objects so that the planets move outwards in response, preserving the angular momentum of the system. These planetesimals then similarly scatter off the next planet they encounter, successively moving the orbits of Uranus, Neptune, and Saturn outwards.[7] Despite the minute movement each exchange of momentum can produce, cumulatively these planetesimal encounters shift (migrate) the orbits of the planets by significant amounts. This process continues until the planetesimals interact with the innermost and most massive giant planet, Jupiter, whose immense gravity sends them into highly elliptical orbits or even ejects them outright from the Solar System. This, in contrast, causes Jupiter to move slightly inward.

The low rate of orbital encounters governs the rate at which planetesimals are lost from the disk, and the corresponding rate of migration. After several hundreds of millions of years of slow, gradual migration, Jupiter and Saturn, the two inmost giant planets, cross their mutual 1:2 mean-motion resonance. This resonance increases their orbital eccentricities, destabilizing the entire planetary system. The arrangement of the giant planets alters quickly and dramatically.[8] Jupiter shifts Saturn out towards its present position, and this relocation causes mutual gravitational encounters between Saturn and the two ice giants, which propel Neptune and Uranus onto much more eccentric orbits. These ice giants then plough into the planetesimal disk, scattering tens of thousands of planetesimals from their formerly stable orbits in the outer Solar System. This disruption almost entirely scatters the primordial disk, removing 99% of its mass, a scenario which explains the modern-day absence of a dense trans-Neptunian population.[5] Some of the planetesimals are thrown into the inner Solar System, producing a sudden influx of impacts on the terrestrial planets: the Late Heavy Bombardment.[4]

Eventually, the giant planets reach their current orbital semi-major axes, and dynamical friction with the remaining planetesimal disc damps their eccentricities and makes the orbits of Uranus and Neptune circular again.[9]

In some 50% of the initial models of Tsiganis and colleagues, Neptune and Uranus also exchange places.[5] An exchange of Uranus and Neptune would be consistent with models of their formation in a disk that had a surface density that declined with distance from the Sun, which predicts that the masses of the planets should also decline with distance from the Sun.[1]

Solar System features

Running dynamical models of the Solar System with different initial conditions for the simulated length of the history of the Solar System will produce the various populations of objects within the Solar System. As the initial conditions of the model are allowed to vary, each population will be more or less numerous, and will have particular orbital properties. Proving a model of the evolution of the early Solar System is difficult, since the evolution cannot be directly observed.[8] However, the success of any dynamical model can be judged by comparing the population predictions from the simulations to astronomical observations of these populations.[8] At the present time, computer models of the Solar System that are begun with the initial conditions of the Nice scenario best match many aspects of the observed Solar System.[10]

The Late Heavy Bombardment

The crater record on the Moon and on the terrestrial planets is part of the main evidence for the Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB): an intensification in the number of impactors, at about 600 million years after the Solar System's formation. In the Nice model icy planetesimals are scattered onto planet-crossing orbits when the outer disc is disrupted by Uranus and Neptune causing a sharp spike of impacts by icy objects. The migration of outer planets also causes mean-motion and secular resonances to sweep through the inner Solar System. In the asteroid belt these excite the eccentricities of the asteroids driving them onto orbits that intersect those of the terrestrial planets causing a more extended period of impacts by stony objects and removing roughly 90% of its mass.[4] The number of planetesimals that would reach the Moon is consistent with the crater record from the LHB.[4] However, the orbital distribution of the remaining asteroids does not match observations.[11] In the outer Solar System the impacts onto Jupiter's moons are sufficient to trigger Ganymede's differentiation but not Callisto's.[12] The impacts of icy planetesimals onto Saturn's inner moons are excessive, however, resulting in the vaporization of their ice.[13]

Trojans and the asteroid belt

After Jupiter and Saturn cross the 2:1 resonance their combined gravitational influence destabilizes the Trojan co-orbital region allowing existing Trojan groups in the L4 and L5 Lagrange points of Jupiter and Neptune to escape and new objects from the outer planetesimal disk to be captured.[14] Objects in the trojan co-orbital region undergo libration, drifting cyclically relative to the L4 and L5 points. When Jupiter and Saturn are near but not in resonance the location where Jupiter passes Saturn relative to their perihelia circulates slowly. If the period of this circulation falls into resonance with the period that the trojans librate the range of their librations can increase until they escape.[6] When this occurs the trojan co-orbital region is "dynamically open" and objects can both escape and enter the region. Primordial trojans escape and a fraction of the numerous objects from the disrupted planetesimal disk temporarily inhabit it.[3] Later when Jupiter and Saturn orbits are farther apart the Trojan region becomes "dynamically closed", and the planetesimals in the trojan region are captured, with many remaining today.[6] The captured trojans have a wide range of inclinations, which had not previously been understood, due to their repeated encounters with the giant planets.[3] The libration angle and eccentricity of the simulated population also matches observations of the orbits of the Jupiter trojans.[6] This mechanism of the Nice model similarly generates the Neptune trojans.[3]

A large number of planetesimals would have also been captured in Jupiter's mean motion resonances as Jupiter migrated inward. Those that remained in a 3:2 resonance with Jupiter form the Hilda family. The eccentricity of other objects declined while they were in a resonance and escaped onto stable orbits in the outer asteroid belt, at distances greater than 2.6 AU as the resonances moved inward.[15] These captured objects would then have undergone collisional erosion, grinding the population away into smaller fragments that can then be acted on by the Yarkovsky effect, causing small objects to drift into unstable resonances, and Poynting–Robertson drag causing smaller grains to drift toward the sun. These processes remove more than 90% of the origin mass implanted into the asteroid belt according to Bottke and colleagues.[16] The size frequency distribution of this simulated population following this erosion are in excellent agreement with observations.[16] This suggests that the Jupiter Trojans, Hildas, and some of the outer asteroid belt, all spectral D-type asteroids, are the remnant planetesimals from this capture and erosion process.[16] It has also been suggested that the dwarf planet Ceres was captured via this process.[17] A few D-type asteroids have been recently discovered with semi-major axes less than 2.5 AU, closer than those that would be captured in the original Nice model.[18]

Outer-system satellites

Any original populations of irregular satellites captured by traditional mechanisms, such as drag or impacts from the accretion disks,[19] would be lost during the encounters between the planets at the time of global system instability.[5] In the Nice model, the outer planets encounter large numbers of planetesimals after Uranus and Neptune enter and disrupt the planetesimal disk. A fraction of these planetesimals are captured by these planets via three-way interactions during encounters between planets. The probability for any planetesimal to be captured by an ice giant is relatively high, a few 10−7.[20] These new satellites could be captured at almost any angle, so unlike the regular satellites of Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, they do not necessarily orbit in the planets' equatorial planes. Some irregulars may have even been exchanged between planets. The resulting irregular orbits match well with the observed populations' semimajor axes, inclinations, and eccentricities.[20] Subsequent collisions between these captured satellites may have created the suspected collisional families seen today.[21] These collisions are also required to erode the population to the present size distribution.[22]

Triton, the largest moon of Neptune, can be explained if it was captured in a three-body interaction involving the disruption of a binary planetoid.[23] Such binary disruption would be more likely if Triton was the smaller member of the binary.[24] However, Triton's capture would be more likely in the early Solar System when the gas disk would damp relative velocities, and binary exchange reactions would not in general have supplied the large number of small irregulars.[24]

There were not enough interactions between Jupiter and the other planets to explain Jupiter's retinue of irregulars in the initial Nice model simulations that reproduced other aspects of the outer Solar System. This suggests either that a second mechanism was at work for that planet, or that the early simulations did not reproduce the evolution of the giant planets orbits.[20]

Formation of the Kuiper belt

The migration of the outer planets is also necessary to account for the existence and properties of the Solar System's outermost regions.[9] Originally, the Kuiper belt was much denser and closer to the Sun, with an outer edge at approximately 30 AU. Its inner edge would have been just beyond the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, which were in turn far closer to the Sun when they formed (most likely in the range of 15–20 AU), and in opposite locations, with Uranus farther from the Sun than Neptune.[4][9]

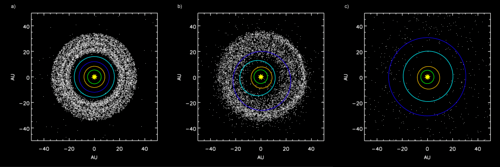

Gravitational encounters between the planets scatter Neptune outward into the planetesimal disk with a semi-major axis of ~28 AU and an eccentricity as high as 0.4. Neptune's high eccentricity causes its mean-motion resonances to overlap and orbits in the region between Neptune and its 2:1 mean motion resonances to become chaotic. The orbits of objects between Neptune and the edge of the planetesimal disk at this time can evolve outward onto stable low-eccentricity orbits within this region. When Neptune's eccentricity is damped by dynamical friction they become trapped on these orbits. These objects form a dynamically-cold belt, since their inclinations remain small during the short time they interact with Neptune. Later, as Neptune migrates outward on a low eccentricity orbit, objects that have been scattered outward are captured into its resonances and can have their eccentricities decline and their inclinations increase due to the Kozai mechanism, allowing them to escape onto stable higher-inclination orbits. Other objects remain captured in resonance, forming the plutinos and other resonant populations. These two population are dynamically hot, with higher inclinations and eccentricities; due to their being scattered outward and the longer period these objects interact with Neptune.[9]

This evolution of Neptune's orbit produces both resonant and non-resonant populations, an outer edge at Neptune's 2:1 resonance, and a small mass relative to the original planetesimal disk. The excess of low-inclination plutinos in other models is avoided due to Neptune being scattered outward, leaving its 3:2 resonance beyond the original edge of the planetesimal disk. The differing initial locations, with the cold classical objects originating primarily from the outer disk, and capture processes, offer explanations for the bi-modal inclination distribution and its correlation with compositions.[9] However, this evolution of Neptune's orbit fails to account for some of the characteristics of the orbital distribution. It predicts a greater average eccentricity in classical Kuiper belt object orbits than is observed (0.10–0.13 versus 0.07) and it does not produce enough higher-inclination objects. It also cannot explain the apparent complete absence of gray objects in the cold population, although it has been suggested that color differences arise in part from surface evolution processes rather than entirely from differences in primordial composition.[25]

The shortage of the lowest-eccentricity objects predicted in the Nice model may indicate that the cold population formed in situ. In addition to their differing orbits the hot and cold populations have but differing colors. The cold population is markedly redder than the hot, suggesting it has a different composition and formed in a different region.[25][26] The cold population also includes a large number of binary objects with loosely bound orbits that would be unlikely to survive close encounter with Neptune.[27] If the cold population formed at its current location, preserving it would require that Neptune's eccentricity remained small,[28] or that its perihelion precessed rapidly due to a strong interaction between it and Uranus.[29]

Scattered disc and Oort cloud

Objects scattered outward by Neptune onto orbits with semi-major axis greater than 50 AU can be captured in resonances forming the resonant population of the scattered disc, or if their eccentricities are reduced while in resonance they can escape from the resonance onto stable orbits in the scattered disc while Neptune is migrating. When Neptune's eccentricity is large its aphelion can reach well beyond its current orbit. Objects that attain perihelia close to or larger than Neptune's at this time can become detached from Neptune when its eccentricity is damped reducing its aphelion, leaving them on stable orbits in the scattered disc.[9]

Objects scattered outward by Uranus and Neptune onto larger orbits (roughly 5,000 AU) can have their perihelion raised by the galactic tide detaching them from the influence of the planets forming the inner Oort cloud with moderate inclinations. Others that reach even larger orbits can be perturbed by nearby stars forming the outer Oort cloud with isotropic inclinations. Objects scattered by Jupiter and Saturn are typically ejected from the Solar System[30] Several percent of the initial planetesimal disc can be deposited in these reservoirs.[31]

Modifications

The Nice model has undergone a number of modifications since its initial publication as the understanding of the formation of the Solar System has advanced and significant differences between its predictions and observations have been identified. Hydrodynamical models of the early Solar System indicate that the orbits of the giant planet converge resulting in their capture into resonances.[32] During the slow approach of Jupiter and Saturn to the 2:1 resonance, Mars can be captured in a secular resonance, exciting its eccentricity to a level that destabilizes the inner Solar System. The eccentricities of the other terrestrial planets can also be excited beyond current levels by sweeping secular resonances after the instability.[33] The orbital distribution of the asteroid belt is also left with an excess of high inclination objects due to secular resonances exciting inclinations and removing low inclination objects.[11] Other differences between predictions and observations included the capture of few irregular satellites by Jupiter, the vaporization of the ice from Saturn's inner moons, a shortage of high inclination objects captured in the Kuiper belt, and the recent discovery of D-type asteroids in the inner asteroid belt.

The first modifications to the Nice model were the initial positions of the giant planets. Investigations of the behavior of planets orbiting in a gas disk using hydrodynamical models reveal that the giant planets would migrate toward the Sun. If the migration continued it would have resulted in Jupiter orbiting close to the Sun like recently discovered exoplanets known as hot Jupiters. Saturn's capture in a resonance with Jupiter prevents this, however, and the later capture of the other planets results in a quadruple resonant configuration with Jupiter and Saturn in their 3:2 resonance.[32] A late instability beginning from this configuration is possible if the outer disk contains Pluto-massed objects. The gravitational stirring of the outer planetesimal disk by these Pluto-massed objects increases their eccentricities and also results in the inward migration of the giant planets. The quadruple resonance of the giant planets is broken when secular resonances are crossed during the inward migration. A late instability similar to the original Nice model then follows. Unlike the original Nice model the timing of this instability is not sensitive to the distance between the outer planet and the planetesimal disk. The combination of resonant planetary orbits and the late instability triggered by these long distant interactions has been referred to as the Nice 2 model.[34]

The second modification was the requirement that one of the ice giants encounters Jupiter, causing its semi-major axis to jump. In this jumping-Jupiter scenario an ice giant encounters Saturn and is scattered inward onto a Jupiter-crossing orbit, causing Saturn's orbit to expand; then encounters Jupiter and is scattered outward, causing Jupiter's orbit to shrink. This results in a step-wise separation of Jupiter's and Saturn's orbits instead of a smooth divergent migration.[33] The step-wise separation of the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn avoids the slow sweeping of secular resonances across the inner solar System that resulted in the excitation of the eccentricities of the terrestrial planets[33] and an asteroid belt with an excessive ratio of high- to low-inclination objects[11] The encounters between the ice giant and Jupiter in this model allow Jupiter to acquire its own irregular satellites.[35] Jupiter trojans are also captured following these encounters when Jupiter's semi-major axis jumps and, if the ice giant passes through one of the libration points scattering trojans, one population is depleted relative to the other.[36] The faster traverse of the secular resonances across the asteroid belt limits the loss of asteroids from its core. Most of the rocky impactors of the Late Heavy Bombardment instead originate from an inner extension that is disrupted when the giant planets reach their current positions, with a remnant remaining as the Hungaria asteroids.[37] Some D-type asteroids are embedded in inner asteroid belt, within 2.5 AU, during encounters with the ice giant when it is crossing the asteroid belt.[38]

Five-planet Nice model

The frequent ejection of the ice giant encountering Jupiter has led David Nesvorný and others to hypothesize an early Solar System with five giant planets, one of which was ejected during the instability.[39][40] This five-planet Nice model begins with the giant planets in a 3:2, 3:2, 2:1, 3:2 resonant chain with a planetesimal disk orbiting beyond them.[41] Following the breaking of the resonant chain Neptune first migrates outward into the planetesimal disk reaching 28 AU before encounters between planets begin.[42] This initial migration reduces the mass of the outer disk enabling Jupiter's eccentricity to be preserved[43] and produces a Kuiper belt with an inclination distribution that matches observations if 20 Earth-masses remained in the planetesimal disk when that migration began.[44] Neptune's eccentricity can remain small during the instability since it only encounters the ejected ice giant, allowing an in situ cold-classical belt to be preserved.[42] The lower mass planetesimal belt in combination with the excitation of inclinations and eccentricities by the Pluto-massed objects also significantly reduce the loss of ice by Saturn's inner moons.[45] The combination of a late breaking of the resonance chain and a migration of Neptune to 28 AU before the instability is unlikely with the Nice 2 model. This gap may be bridged by a slow dust-driven migration over several million years following an early escape from resonance.[46] A recent study found that the five-planet Nice model has a statistically small likelihood of reproducing the orbits of the terrestrial planets. Although this implies that the instability occurred before the formation of the terrestrial planets and could not be the source of the Late Heavy Bombardment,[47][48] the advantage of an early instability is reduced by the sizable jumps in the semi-major axis of Jupiter and Saturn required to preserve the asteroid belt.[49][50]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Solving solar system quandaries is simple: Just flip-flop the position of Uranus and Neptune". Press release. Arizona State University. 11 Dec 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- ↑ Desch, S. (2007). "Mass Distribution and Planet Formation in the Solar Nebula". The Astrophysical Journal. 671 (1): 878–893. Bibcode:2007ApJ...671..878D. doi:10.1086/522825.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Crida, A. (2009). "Solar System formation". Reviews in Modern Astronomy. 21: 3008. arXiv:0903.3008. Bibcode:2009RvMA...21..215C. doi:10.1002/9783527629190.ch12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 R. Gomes; H. F. Levison; K. Tsiganis; A. Morbidelli (2005). "Origin of the cataclysmic Late Heavy Bombardment period of the terrestrial planets". Nature. 435 (7041): 466–9. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..466G. doi:10.1038/nature03676. PMID 15917802.

- 1 2 3 4 Tsiganis, K.; Gomes, R.; Morbidelli, A.; F. Levison, H. (2005). "Origin of the orbital architecture of the giant planets of the Solar System" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7041): 459–461. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..459T. doi:10.1038/nature03539. PMID 15917800.

- 1 2 3 4 Morbidelli, A.; Levison, H.F.; Tsiganis, K.; Gomes, R. (2005). "Chaotic capture of Jupiter's Trojan asteroids in the early Solar System" (PDF). Nature. 435 (7041): 462–465. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..462M. doi:10.1038/nature03540. OCLC 112222497. PMID 15917801.

- 1 2 G. Jeffrey Taylor (21 August 2001). "Uranus, Neptune, and the Mountains of the Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries. Hawaii Institute of Geophysics & Planetology. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- 1 2 3 Hansen, Kathryn (June 7, 2005). "Orbital shuffle for early solar system". Geotimes. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Levison HF, Morbidelli A, Van Laerhoven C, Gomes RS, Tsiganis K (2007). "Origin of the Structure of the Kuiper Belt during a Dynamical Instability in the Orbits of Uranus and Neptune". Icarus. 196 (1): 258–273. arXiv:0712.0553. Bibcode:2008Icar..196..258L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.035.

- ↑ T. V. Johnson; J. C. Castillo-Rogez; D. L. Matson; A. Morbidelli; J. I. Lunine. "Constraints on outer Solar System early chronology" (PDF). Early Solar System Impact Bombardment conference (2008). Retrieved 2008-10-18.

- 1 2 3 Morbidelli, Alessandro; Brasser, Ramon; Gomes, Rodney; Levison, Harold F.; Tsiganis, Kleomenis (2010). "Evidence from the Asteroid Belt for a Violent Past Evolution of Jupiter's Orbit". The Astronomical Journal. 140 (5): 1391–1501. arXiv:1009.1521. Bibcode:2010AJ....140.1391M. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/140/5/1391.

- ↑ Baldwin, Emily. "Comet impacts explain Ganymede-Callisto dichotomy". Astronomy Now. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ↑ Nimmo, F.; Korycansky, D. G. (2012). "Impact-driven ice loss in outer Solar System satellites: Consequences for the Late Heavy Bombardment". Icarus. 219 (1): 508–510. Bibcode:2012Icar..219..508N. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2012.01.016.

- ↑ Levison, Harold F.; Shoemaker, Eugene M.; Shoemaker, Carolyn S. (1997). "Dynamical evolution of Jupiter's Trojan asteroids". Nature. 385 (6611): 42–44. Bibcode:1997Natur.385...42L. doi:10.1038/385042a0.

- ↑ Levison, Harold F.; Bottke, William F.; Gounelle, Matthieu; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Nesvorny, David; Tsiganis, Kleomeis (2009). "Contamination of the asteroid belt by primordial trans-Neptunian objects". Nature. 460 (7253): 364–366. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..364L. doi:10.1038/nature08094. PMID 19606143.

- 1 2 3 Bottke, W. F.; Levison, H. F.; Morbidelli, A.; Tsiganis, K. (2008). "The Collisional Evolution of Objects Captured in the Outer Asteroid Belt During the Late Heavy Bombardment". 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 39th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. 39 (LPI Contribution No. 1391): 1447. Bibcode:2008LPI....39.1447B.

- ↑ William B. McKinnon (2008). "On The Possibility Of Large KBOs Being Injected Into The Outer Asteroid Belt". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 40: 464. Bibcode:2008DPS....40.3803M.

- ↑ DeMeo, Francesca E.; Binzel, Richard P.; Carry, Benoît; Polishook, David; Moskovitz, Nicholas A, (2014). "Unexpected D-type interlopers in the inner main belt". Icarus. 229: 392–399. arXiv:1312.2962. Bibcode:2014Icar..229..392D. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.026.

- ↑ Turrini & Marzari, 2008, Phoebe and Saturn's irregular satellites: implications for the collisional capture scenario Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Nesvorný, D.; Vokrouhlický, D.; Morbidelli, A. (2007). "Capture of Irregular Satellits during Planetary Encounters". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (5): 1962–1976. Bibcode:2007AJ....133.1962N. doi:10.1086/512850.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David; Beaugé, Cristian; Dones, Luke (2004). "Collisional Origin of Families of Irregular Satellites". The Astronomical Journal. 127 (3): 1768–1783. Bibcode:2004AJ....127.1768N. doi:10.1086/382099.

- ↑ Bottke, William F.; Nesvorný, David; Vokrouhlick, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2010). "The Irregular Satellites: The Most Collisionally Evolved Populations in the Solar System". The Astronomical Journal. 139 (3): 994–1014. Bibcode:2010AJ....139..994B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/139/3/994.

- ↑ Agnor, Craig B.; Hamilton, Douglas B. (2006). "Neptune's capture of its moon Triton in a binary-planet gravitational encounter". Nature. 441 (7090): 192–194. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..192A. doi:10.1038/nature04792. PMID 16688170.

- 1 2 Vokrouhlický, David; Nesvorný, David; Levison, Harold F. (2008). "Irregular Satellite Capture by Exchange Reactions". The Astronomical Journal. 136 (4): 1463–1476. Bibcode:2008AJ....136.1463V. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.4097. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/136/4/1463.

- 1 2 Levison, Harold F.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; VanLaerhoven, Christa; Gomes, Rodney S. (2008-04-03). "Origin of the structure of the Kuiper belt during a dynamical instability in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune". Icarus. 196 (1): 258–273. arXiv:0712.0553. Bibcode:2008Icar..196..258L. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.11.035. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ↑ Morbidelli, Alessandro (2006). "Origin and dynamical evolution of comets and their reservoirs". arXiv:astro-ph/0512256

|class=ignored (help). - ↑ Lovett, Rick (2010). "Kuiper Belt may be born of collisions". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2010.522.

- ↑ Wolff, Schuyler; Dawson, Rebekah I.; Murray-Clay, Ruth A. (2012). "Neptune on Tiptoes: Dynamical Histories that Preserve the Cold Classical Kuiper Belt". The Astrophysical Journal. 746 (2): 171. arXiv:1112.1954. Bibcode:2012ApJ...746..171W. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/746/2/171.

- ↑ Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E.; Fraser, Wesley (2011). "Retention of a Primordial Cold Classical Kuiper Belt in an Instability-Driven Model of Solar System Formation". The Astrophysical Journal. 738 (1): 13. arXiv:1106.0937. Bibcode:2011ApJ...738...13B. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/738/1/13.

- ↑ Dones, L.; Weissman, P. R.; Levison, H. F.; Duncan, M. J. (2004). "Oort cloud formation and dynamics". Comets II: 153–174. Bibcode:2004ASPC..323..371D.

- ↑ Brasser, R.; Morbidelli, A. (2013). "Oort cloud and Scattered Disc formation during a late dynamical instability in the Solar System". Icarus. 225 (1): 40.49. arXiv:1303.3098. Bibcode:2013Icar..225...40B. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2013.03.012.

- 1 2 Morbidelli, Alessandro; Tsiganis, Kleomenis; Crida, Aurélien; Levison, Harold F.; Gomes, Rodney (2007). "Dynamics of the Giant Planets of the Solar System in the Gaseous Protoplanetary Disk and Their Relationship to the Current Orbital Architecture". The Astronomical Journal. 134 (5): 1790–1798. arXiv:0706.1713. Bibcode:2007AJ....134.1790M. doi:10.1086/521705.

- 1 2 3 Brasser, R.; Morbidelli, A.; Gomes, R.; Tsiganis, K.; Levison, H. F. (2009). "Constructing the secular architecture of the solar system II: the terrestrial planets". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 507 (2): 1053–1065. arXiv:0909.1891. Bibcode:2009A&A...507.1053B. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200912878.

- ↑ Levison, Harold F.; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Tsiganis, Kleomenis; Nesvorný, David; Gomes, Rodney (2011). "Late Orbital Instabilities in the Outer Planets Induced by Interaction with a Self-gravitating Planetesimal Disk" (PDF). The Astronomical Journal. 142 (5): 152. Bibcode:2011AJ....142..152L. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/142/5/152.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David; Vokrouhlický, David; Deienno, Rogerio. "Capture of Irregular Satellites at Jupiter". The Astrophysical Journal. 784 (1): 22. arXiv:1401.0253. Bibcode:2014ApJ...784...22N. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/784/1/22.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David; Vokrouhlický, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2013). "Capture of Trojans by Jumping Jupiter". The Astrophysical Journal. 768 (1): 45. arXiv:1303.2900. Bibcode:2013ApJ...768...45N. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/768/1/45.

- ↑ Bottke, William F.; Vokrouhlický, David; Minton, David; Nesvorný, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Brasser, Ramon; Simonson, Bruce; Levison, Harold F. (2012). "An Archaean heavy bombardment from a destabilized extension of the asteroid belt". Nature. 485 (7396): 78–81. Bibcode:2012Natur.485...78B. doi:10.1038/nature10967. PMID 22535245.

- ↑ Vokrouhlický, David; Bottke, William F.; Nesvorný, David (2016). "Capture of Trans-Neptunian Planetesimals in the Main Asteroid Belt". The Astronomical Journal. 152 (2): 39. Bibcode:2016AJ....152...39V. doi:10.3847/0004-6256/152/2/39.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David. "Young Solar System's Fifth Giant Planet?". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 742 (2): L22. arXiv:1109.2949. Bibcode:2011ApJ...742L..22N. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/742/2/L22.

- ↑ Batygin, Konstantin; Brown, Michael E.; Betts, Hayden (2012). "Instability-driven Dynamical Evolution Model of a Primordially Five-planet Outer Solar System". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 744 (1): L3. arXiv:1111.3682. Bibcode:2012ApJ...744L...3B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/744/1/L3.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2012). "Statistical Study of the Early Solar System's Instability with Four, Five, and Six Giant Planets". The Astronomical Journal. 144 (4): 17. arXiv:1208.2957. Bibcode:2012AJ....144..117N. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/144/4/117.

- 1 2 Nesvorný, David (2015). "Jumping Neptune Can Explain the Kuiper Belt Kernel". The Astronomical Journal. 150 (3): 68. arXiv:1506.06019. Bibcode:2015AJ....150...68N. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/3/68.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David; Morbidelli, Alessandro (2012). "Statistical Study of the Early Solar System's Instability with Four, Five, and Six Giant Planets". The Astronomical Journal. 144 (4): 117. arXiv:1208.2957. Bibcode:2012AJ....144..117N. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/144/4/117.

- ↑ Nesvorný, David (2015). "Evidence for Slow Migration of Neptune from the Inclination Distribution of Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astronomical Journal. 150 (3): 73. arXiv:1504.06021. Bibcode:2015AJ....150...73N. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/150/3/73.

- ↑ Dones, L.; Levison, H. L. "The Impact Rate on Giant Planet Satellites During the Late Heavy Bombardment" (PDF). 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013).

- ↑ Deienno, Rogerio; Morbidelli, Alessandro; Gomes, Rodney S.; Nesvorny, David (2017). "Constraining the giant planets' initial configuration from their evolution: implications for the timing of the planetary instability". The Astronomical Journal. 153: 153. arXiv:1702.02094. Bibcode:2017AJ....153..153D. doi:10.3847/1538-3881/aa5eaa.

- ↑ Kaib, Nathan A.; Chambers, John E. (2016). "The fragility of the terrestrial planets during a giant-planet instability". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 455 (4): 3561–3569. arXiv:1510.08448. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.455.3561K. doi:10.1093/mnras/stv2554.

- ↑ Siegel, Ethan. "Jupiter May Have Ejected A Planet From Our Solar System". Starts With a Bang. forbes.com. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ↑ Walsh, K. J.; Morbidelli, A. (2011). "The effect of an early planetesimal-driven migration of the giant planets on terrestrial planet formation". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 526: A126. arXiv:1101.3776. Bibcode:2011A&A...526A.126W. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201015277.

- ↑ Toliou, A.; Morbidelli, A.; Tsiganis, K. (2016). "Magnitude and timing of the giant planet instability: A reassessment from the perspective of the asteroid belt". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 592: A72. arXiv:1606.04330. Bibcode:2016A&A...592A..72T. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201628658.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nice Model. |