Makemake

.jpg) Makemake and its moon (indicated by the arrow), as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | |

| Discovery date | March 31, 2005 |

| Designations | |

| MPC designation | (136472) Makemake |

| Pronunciation |

/ˌmækiˈmæki/, /ˌmɑːkiˈmɑːki/ or /ˌmɑːkeɪˈmɑːkeɪ/ ( |

Named after | Makemake |

| 2005 FY9 | |

|

Dwarf planet cubewano[5] scattered-near[lower-alpha 2] | |

| Adjectives | Makemakean |

| Orbital characteristics[6] | |

| Epoch JD 2457000.5 (9 December 2014) | |

| Earliest precovery date | January 29, 1955 |

| Aphelion | 52.840 AU |

| Perihelion | 38.590 AU |

| 45.715 AU | |

| Eccentricity | 0.15586 |

| 309.09 yr (112,897 d) | |

Average orbital speed | 4.419 km/s |

| 15 | |

| Inclination | 29.00685° |

| 79.3659° | |

| 297.240° | |

| Known satellites | 1 |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | |

Mean radius | |

| Flattening | 0.05[lower-alpha 3] |

| (6.9±0.3)×106 km2[lower-alpha 4][9] | |

| Volume | (1.7±0.1)×109 km3[lower-alpha 4][10] |

| Mass | < 4.4 × 1021 kg |

Mean density | 1.4–3.2 g/cm3[7] <3.05 g/cm3 |

Sidereal rotation period | 7.771±0.003 h[11] |

|

0.81+0.03 −0.05[7] | |

| Temperature |

32–36 K (single-terrain model) 40–44 K (two-terrain model)[8] |

| B−V=0.83, V−R=0.5[12] | |

| 17.0 (opposition)[13][14] | |

| −0.3[6] | |

|

| |

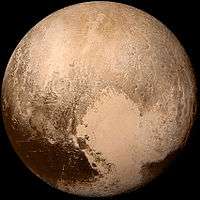

Makemake (minor-planet designation 136472 Makemake) is a dwarf planet and perhaps the largest Kuiper belt[lower-alpha 5] object in the classical population,[lower-alpha 2] with a diameter approximately two-thirds that of Pluto.[19][20] Makemake has one known satellite, S/2015 (136472) 1.[21] Makemake's extremely low average temperature, about 30 K (−243.2 °C), means its surface is covered with methane, ethane, and possibly nitrogen ices.[16]

Makemake was discovered on March 31, 2005, by a team led by Michael E. Brown, and announced on July 29, 2005. Initially, it was known as 2005 FY9 and later given the minor-planet number 136472. Makemake was recognized as a dwarf planet by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in July 2008.[20][22][23][24] Its name derives from Makemake in the mythology of the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island.[20]

History

Discovery

Makemake was discovered on March 31, 2005, by a team at the Palomar Observatory, led by Michael E. Brown,[6] and was announced to the public on July 29, 2005. The team had planned to delay announcing their discoveries of the bright objects Makemake and Eris until further observations and calculations were complete, but announced them both on July 29 when the discovery of another large object they had been tracking, Haumea, was controversially announced on July 27 by a different team in Spain.[25]

Despite its relative brightness (it is about a fifth as bright as Pluto),[lower-alpha 6] Makemake was not discovered until after many much fainter Kuiper belt objects. Most searches for minor planets are conducted relatively close to the ecliptic (the region of the sky that the Sun, Moon and planets appear to lie in, as seen from Earth), due to the greater likelihood of finding objects there. It probably escaped detection during the earlier surveys due to its relatively high orbital inclination, and the fact that it was at its farthest distance from the ecliptic at the time of its discovery, in the northern constellation of Coma Berenices.[14]

Precovery images have been identified back to January 29, 1955.[6]

Besides Pluto, Makemake is the only other dwarf planet that was bright enough that Clyde Tombaugh could have detected it during his search for trans-Neptunian planets around 1930.[27] At the time of Tombaugh's survey, Makemake was only a few degrees from the ecliptic, near the border of Taurus and Auriga,[lower-alpha 7] at an apparent magnitude of 16.0.[14] This position, however, was also very near the Milky Way, and Makemake would have been almost impossible to find against the dense background of stars. Tombaugh continued searching for some years after the discovery of Pluto,[28] but he did not find Makemake or any other trans-Neptunian objects.

Name

The provisional designation 2005 FY9 was given to Makemake when the discovery was made public. Before that, the discovery team used the codename "Easterbunny" for the object, because of its discovery shortly after Easter.[1]

In July 2008, in accordance with IAU rules for classical Kuiper belt objects, 2005 FY9 was given the name of a creator deity.[29] The name of Makemake, the creator of humanity and god of fertility in the myths of the Rapa Nui, the native people of Easter Island,[23] was chosen in part to preserve the object's connection with Easter.[1]

Orbit and classification

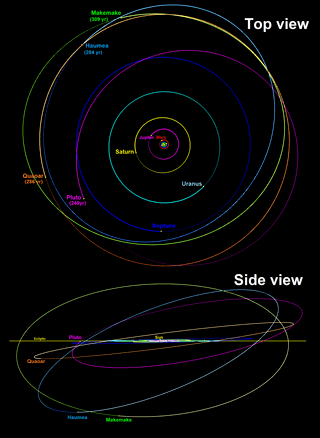

As of December 2015, Makemake is 52.4 AU (7.84×109 km) from the Sun,[13][14] almost as far from the Sun as it ever reaches on its orbit.[16] Makemake follows an orbit very similar to that of Haumea: highly inclined at 29° and a moderate eccentricity of about 0.16.[30] Nevertheless, Makemake's orbit is slightly farther from the Sun in terms of both the semi-major axis and perihelion. Its orbital period is nearly 310 years,[15] more than Pluto's 248 years and Haumea's 283 years. Both Makemake and Haumea are currently far from the ecliptic—the angular distance is almost 29°. Makemake is approaching its 2033 aphelion,[14] whereas Haumea passed its aphelion in early 1992.[31]

Makemake is a classical Kuiper belt object (KBO),[5][lower-alpha 2] which means its orbit lies far enough from Neptune to remain stable over the age of the Solar System.[32][33] Unlike plutinos, which can cross Neptune's orbit due to their 2:3 resonance with the planet, the classical objects have perihelia further from the Sun, free from Neptune's perturbation.[32] Such objects have relatively low eccentricities (e below 0.2) and orbit the Sun in much the same way the planets do. Makemake, however, is a member of the "dynamically hot" class of classical KBOs, meaning that it has a high inclination compared to others in its population.[34] Makemake is, probably coincidentally, near the 11:6 resonance with Neptune.[35]

Physical characteristics

Brightness, size, and rotation

Makemake is currently visually the second-brightest Kuiper belt object after Pluto,[27] having a March opposition apparent magnitude of 17.0[13] in the constellation Coma Berenices.[14] This is bright enough to be visible using a high-end amateur telescope.

Combining the detection in infrared by the Spitzer Space Telescope and Herschel Space Telescope with the similarities of spectrum with Pluto yielded an estimated diameter from 1,360 to 1,480 km.[19] From the 2011 stellar occultation by Makemake, its dimensions have been initially measured to be (1502 ± 45) × (1430 ± 9) km. However, this analysis of the occultation data was later reanalyzed,[7] which led to the dimension estimate of (1434+48

−18) × (1420+18

−24 km) without a pole-orientation constraint.[7] This means that Makemake is slightly larger than Haumea, making it likely the fourth-largest-known trans-Neptunian object after Pluto, Eris, and 2007 OR10, though the error bars with the latter overlap.[30] Makemake was the fourth dwarf planet recognized, because it has a bright V-band absolute magnitude of −0.44.[6] Makemake has a high geometrical albedo of 0.81+0.01

−0.02.[7]

The rotation period of Makemake is estimated at 7.77 hours. Its lightcurve amplitude is small, only 0.03 mag.[7] This was thought to be due to Makemake currently being viewed pole on from Earth; however, S/2015 (136472) 1's orbital plane (which is probably orbiting with little inclination relative to Makemake's equator due to tides resulting from its rapid rotation) is edge-on from Earth, implying that Makemake is really being viewed equator-on.[36]

Spectra and surface

Like Pluto, Makemake appears red in the visible spectrum, and significantly redder than the surface of Eris (see colour comparison of TNOs).[37] The near-infrared spectrum is marked by the presence of the broad methane (CH4) absorption bands. Methane is observed also on Pluto and Eris, but its spectral signature is much weaker.[37]

Spectral analysis of Makemake's surface revealed that methane must be present in the form of large grains at least one centimetre in size.[16] In addition to methane, large amounts of ethane and tholins as well as smaller amounts of ethylene, acetylene and high-mass alkanes (like propane) may be present, most likely created by photolysis of methane by solar radiation.[16][38] The tholins are probably responsible for the red color of the visible spectrum. Although evidence exists for the presence of nitrogen ice on its surface, at least mixed with other ices, there is nowhere near the same level of nitrogen as on Pluto and Triton, where it composes more than 98 percent of the crust. The relative lack of nitrogen ice suggests that its supply of nitrogen has somehow been depleted over the age of the Solar System.[16][39][40]

The far-infrared (24–70 μm) and submillimeter (70–500 μm) photometry performed by Spitzer and Herschel telescopes revealed that the surface of Makemake is not homogeneous. Although the majority of it is covered by nitrogen and methane ices, where the albedo ranges from 78 to 90%, there are small patches of dark terrain whose albedo is only 2 to 12%, and that make up 3 to 7% of the surface.[19] These studies were made before S/2015 (136472) 1 was discovered; thus, these small dark patches may actually have been the dark surface of the satellite rather than any actual surface features on Makemake[36].However, some experiments have refuted these studies. Spectroscopic studies, collected from 2005 to 2008 using the William Herschel Telescope (La Palma, Spain) were analyzed together with other spectra in the literature, as of 2014. They show some degree of variation in the spectral slope, which would be associated with different abundance of the complex organic materials, byproduct of the irradiation of the ices present on the surface of Makemake. However, the relative ratio of the two dominant icy species, methane and nitrogen, remains quite stable on the surface revealing a low degree of inhomogeneity in the ice component.[41] These results have been recently confirmed when the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo acquired new visible and near infra-red spectra for Makemake, between 2006 and 2013, that covered nearly 80% of its surface; this study found that the variation in the spectra were negligible, suggesting that Makemake's surface may indeed be homogenous.[42]

Atmosphere

Makemake was expected to have an atmosphere similar to that of Pluto but with a lower surface pressure. However, on 23 April 2011 Makemake passed in front of an 18th-magnitude star and abruptly blocked its light.[43] The results showed that Makemake presently lacks a substantial atmosphere and placed an upper limit of 4–12 nanobar on the pressure at its surface.[8]

The presence of methane and possibly nitrogen suggests that Makemake could have a transient atmosphere similar to that of Pluto near its perihelion.[37] Nitrogen, if present, will be the dominant component of it.[16] The existence of an atmosphere also provides a natural explanation for the nitrogen depletion: because the gravity of Makemake is weaker than that of Pluto, Eris and Triton, a large amount of nitrogen was probably lost via atmospheric escape; methane is lighter than nitrogen, but has significantly lower vapor pressure at temperatures prevalent at the surface of Makemake (32–36 K),[8] which hinders its escape; the result of this process is a higher relative abundance of methane.[44] However, studies of Pluto's atmosphere by New Horizons suggest that methane, not nitrogen, is the dominant escaping gas, suggesting that the reasons for Makemake's absence of nitrogen may be more complicated.[45][46]

Satellite

|

Makemake and its moon | |

| Discovery[47] | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by |

|

| Discovery date | April 2015 |

| Designations | |

| Pronunciation | // |

| MK 2 (unofficial)[48] | |

| Orbital characteristics[47] | |

| 21,000 km to 300,000 km | |

| 12.4 days to 660 days | |

| Satellite of | Makemake |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | ~87.5km |

| ~0.1 | |

| 25.1 | |

|

| |

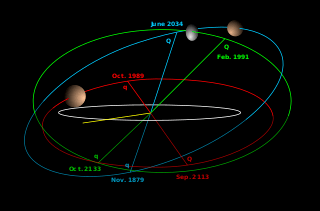

S/2015 (136472) 1, nicknamed MK 2 by the discovery team,[48] is the only known moon of Makemake.[47][49][50] It is estimated to be 175 km (110 mi) in diameter (for an assumed albedo of 4%) and has a semi-major axis at least 21,000 km (13,000 mi) from Makemake.[51] Its orbital period is ≥ 12 days (the minimum values are those for a circular orbit; the actual orbital eccentricity is unknown).[52][47][50] Observations leading to its discovery occurred in April 2015, using the Hubble Space Telescope's Wide Field Camera 3, and its discovery was announced on 26 April 2016.[48]

Most other large trans-Neptunian objects have at least one known satellite: Eris has one, Haumea has two, Pluto has five, and 2007 OR10 has one satellite. 10% to 20% of all trans-Neptunian objects are expected to have one or more satellites.[27] Because satellites offer a simple method to measure an object's mass, Makemake's satellite should lead to better estimates of its mass.[27]

Observations

A preliminary examination of the imagery suggests that S/2015 (136472) 1 has a reflectivity similar to charcoal, making it an extremely dark object. This is somewhat surprising because Makemake is the second-brightest-known object in the Kuiper belt. One hypothesis to explain this is that its gravity is not strong enough to prevent bright but volatile ices from being lost to space when it is heated by the distant Sun.[53]

Further observations will be needed in order to determine S/2015 (136472) 1's orbit. If it is circular, it would suggest that S/2015 (136472) 1 was formed by an ancient impact event, but if it is elliptical, it suggests that it may have been captured.[53]

Alex Parker, the leader of the team that performed the analysis of the images at the Southwest Research Institute, said that S/2015 (136472) 1's orbit appears to be aligned edge-on to Earth-based observatories. This would make it much more difficult to detect because it would be lost in Makemake's glare much of the time, which, along with its dark surface, would contribute to previous surveys failing to observe it.[53]

Exploration

It was calculated that a flyby mission to Makemake could take just over 16 years using a Jupiter gravity assist, based on a launch date of 21 August 2024 or 24 August 2036. Makemake would be approximately 52 AU from the Sun when the spacecraft arrives.[54]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The Rapa Nui pronunciation is [ˈmakeˈmake], which is approximated in English as US: /ˌmɑːkiˈmɑːki/ MAH-kee-MAH-kee,[1] UK: /ˈmækiˈmæki/ MAK-ee-MAK-ee, or as /ˌmɑːkeɪˈmɑːkeɪ/ MAH-kay-MAH-kay.[2][3] The first is an anglicized pronunciation; the second is more Polynesian, and is used by Brown and his students.[4]

- 1 2 3 Astronomers Mike Brown, David Jewitt and Marc Buie classify Makemake as a near scattered object but the Minor Planet Center, from which Wikipedia draws most of its definitions for the trans-Neptunian population, places it among the main Kuiper belt population.[15][16][17][18]

- ↑ Calculated using (a−b)/a and the dimensions from [8]

- 1 2 Calculated using the dimensions from [8] assuming an oblate spheroid.

- ↑ The Kuiper Belt is a ring of bodies beyond Neptune.

- ↑ It has an apparent magnitude in opposition of 16.7 vs. 15 for Pluto.[26]

- ↑ Based on Minor Planet Center online Minor Planet Ephemeris Service: March 1, 1930: RA: 05h51m, Dec: +29.0.

References

- 1 2 3 Brown, Mike (2008). "Mike Brown's Planets: What's in a name? (part 2)". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Brown, Mike (2008). "Mike Brown's Planets: Make-make". California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ Robert D. Craig (2004). Handbook of Polynesian Mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-57607-894-5.

- ↑ Podcast Dwarf Planet Haumea (Darin Ragozzine, at 3′11″)

- 1 2 "MPEC 2009-P26 :Distant Minor Planets (2009 AUG. 17.0 TT)". IAU Minor Planet Center. 2009-08-07. Retrieved 2009-08-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 136472 Makemake (2005 FY9)". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (2014-07-08 last obs). Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 M.E. Brown (2013). "On the size, shape, and density of dwarf planet Makemake". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 767: L7(5pp). arXiv:1304.1041v1. Bibcode:2013ApJ...767L...7B. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/767/1/L7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ortiz, J. L.; Sicardy, B.; Braga-Ribas, F.; Alvarez-Candal, A.; Lellouch, E.; Duffard, R.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Ivanov, V. D.; Littlefair, S. P.; Camargo, J. I. B.; Assafin, M.; Unda-Sanzana, E.; Jehin, E.; Morales, N.; Tancredi, G.; Gil-Hutton, R.; De La Cueva, I.; Colque, J. P.; Da Silva Neto, D. N.; Manfroid, J.; Thirouin, A.; Gutiérrez, P. J.; Lecacheux, J.; Gillon, M.; Maury, A.; Colas, F.; Licandro, J.; Mueller, T.; Jacques, C.; Weaver, D. (2012). "Albedo and atmospheric constraints of dwarf planet Makemake from a stellar occultation". Nature. 491 (7425): 566–569. Bibcode:2012Natur.491..566O. doi:10.1038/nature11597. PMID 23172214. (ESO 21 November 2012 press release: Dwarf Planet Makemake Lacks Atmosphere)

- ↑ "surface ellipsoid 751x751x715 – Wolfram-Alpha".

- ↑ "volume ellipsoid 751x751x715 – Wolfram-Alpha".

- ↑ A. N. Heinze and Daniel deLahunta, The rotation period and light-curve amplitude of Kuiper belt dwarf planet 136472 Makemake (2005 FY9), The Astronomical Journal 138 (2009), pp. 428–438. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/138/2/428

- ↑ Snodgrass, C.; Carry, B.; Dumas, C.; Hainaut, O. (February 2010). "Characterisation of candidate members of (136108) Haumea's family". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 511: A72. arXiv:0912.3171. Bibcode:2010A&A...511A..72S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200913031.

- 1 2 3 "AstDys (136472) Makemake Ephemerides". Department of Mathematics, University of Pisa, Italy. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Asteroid 136472 Makemake (2005 FY9)". HORIZONS Web-Interface. JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2015-12-30.

- 1 2 Marc W. Buie (2008-04-05). "Orbit Fit and Astrometric record for 136472". SwRI (Space Science Department). Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mike Brown; K. M. Barksume; G. L. Blake; E. L. Schaller; et al. (2007). "Methane and Ethane on the Bright Kuiper Belt Object 2005 FY9". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (1): 284–289. Bibcode:2007AJ....133..284B. doi:10.1086/509734.

- ↑ Audrey Delsanti; David Jewitt. "The Solar System Beyond The Planets" (PDF). University of Hawaii. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ "List Of Transneptunian Objects". Minor Planet Center. Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- 1 2 3 T.L. Lim; J. Stansberry; T.G. Müller (2010). ""TNOs are Cool": A survey of the trans-Neptunian region III. Thermophysical properties of 90482 Orcus and 136472 Makemake". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 518: L148. arXiv:1202.3657. Bibcode:2010A&A...518L.148L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201014701.

- 1 2 3 International Astronomical Union (2008-07-19). "Fourth dwarf planet named Makemake" (Press release). International Astronomical Union (News Release – IAU0806). Retrieved 2008-07-20.

- ↑ HubbleSite (2016-04-26). "Hubble Discovers Moon Orbiting the Dwarf Planet Makemake" (Press release). HubbleSite (News Release no. STScI-2016-18). Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- ↑ Michael E. Brown. "The Dwarf Planets". California Institute of Technology, Department of Geological Sciences. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

- 1 2 "Dwarf Planets and their Systems". Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature (WGPSN). U.S. Geological Survey. 2008-11-07. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ Gonzalo Tancredi; Sofia Favre (June 2008). "Which are the dwarfs in the Solar System?" (PDF). Icarus. 195 (2): 851–862. Bibcode:2008Icar..195..851T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.12.020. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- ↑ Thomas H. Maugh II & John Johnson Jr. (2005-10-16). "His Stellar Discovery Is Eclipsed". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2008-07-14.

- ↑ David L. Rabinowitz; Bradley E. Schaefer; Suzanne W. Tourtellotte (2007). "The Diverse Solar Phase Curves of Distant Icy Bodies. I. Photometric Observations of 18 Trans-Neptunian Objects, 7 Centaurs, and Nereid". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (1): 26–43. arXiv:astro-ph/0605745. Bibcode:2007AJ....133...26R. doi:10.1086/508931.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, M. E.; Van Dam, M. A.; Bouchez, A. H.; Le Mignant, D.; Campbell, R. D.; Chin, J. C. Y.; Conrad, A.; Hartman, S. K.; Johansson, E. M.; Lafon, R. E.; Rabinowitz, D. L. Rabinowitz; Stomski, P. J., Jr.; Summers, D. M.; Trujillo, C. A.; Wizinowich, P. L. (2006). "Satellites of the Largest Kuiper Belt Objects" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 639 (1): L43–L46. arXiv:astro-ph/0510029. Bibcode:2006ApJ...639L..43B. doi:10.1086/501524. Retrieved 2011-10-19.

- ↑ "Clyde W. Tombaugh". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ "Makemake Becomes the Newest Dwarf Planet". Slashdot. July 13, 2008. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- 1 2 S. C. Tegler; W. M. Grundy; W. Romanishin; G. J. Consolmagno; et al. (2007-01-08). "Optical Spectroscopy of the Large Kuiper Belt Objects 136472 (2005 FY9) and 136108 (2003 EL61)". The Astronomical Journal. 133 (2): 526–530. arXiv:astro-ph/0611135. Bibcode:2007AJ....133..526T. doi:10.1086/510134.

- ↑ "Asteroid 136108 (2003 EL61)". HORIZONS Web-Interface. JPL Solar System Dynamics. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- 1 2 David Jewitt (February 2000). "Classical Kuiper Belt Objects (CKBOs)". University of Hawaii. Archived from the original on August 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Jane X. Luu & David C. Jewitt (2002). "Kuiper Belt Objects: Relics from the Accretion Disk of the Sun" (PDF). Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 40 (1): 63–101. Bibcode:2002ARA&A..40...63L. doi:10.1146/annurev.astro.40.060401.093818. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Levison, H. F.; Morbidelli, A. (2003-11-27). "The formation of the Kuiper belt by the outward transport of bodies during Neptune's migration". Nature. 426 (6965): 419–421. Bibcode:2003Natur.426..419L. doi:10.1038/nature02120. PMID 14647375. Retrieved 2012-05-26.

- ↑ Preliminary simulation of Makemake (2005 FY9)'s orbit and the 2009-02-04 nominal (non-librating) rotating frame for Makemake. See (182294) 2001 KU76 for a proper 11:6 resonance libration.

- 1 2 "A Moon for Makemake". www.planetary.org.

- 1 2 3 J. Licandro; N. Pinilla-Alonso; M. Pedani; E. Oliva; et al. (2006). "The methane ice rich surface of large TNO 2005 FY9: a Pluto-twin in the trans-neptunian belt?". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 445 (3): L35–L38. Bibcode:2006A&A...445L..35L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500219.

- ↑ M. E. Brown; E. L. Schaller; G. A. Blake (2015). "Irradiation products on the dwarf planet Makemake". The Astronomical Journal. 149: 105(6p). Bibcode:2015AJ....149..105B. doi:10.1088/0004-6256/149/3/105.

- ↑ S.C. Tegler; W.M. Grundy; F. Vilas; W. Romanishin; et al. (June 2008). "Evidence of N2-ice on the surface of the icy dwarf Planet 136472 (2005 FY9)". Icarus. 195 (2): 844–850. arXiv:0801.3115. Bibcode:2008Icar..195..844T. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.12.015.

- ↑ Tobias C. Owen, Ted L. Roush, et al. (1993-08-06). "Surface Ices and the Atmospheric Composition of Pluto". Science. 261 (5122): 745–748. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..745O. doi:10.1126/science.261.5122.745. PMID 17757212.

- ↑ Lorenzi, V.; Pinilla-Alonso, N.; Licandro, J. (2015-05-01). "Rotationally resolved spectroscopy of dwarf planet (136472) Makemake". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 577. arXiv:1504.02350. Bibcode:2015A&A...577A..86L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201425575. ISSN 0004-6361.

- ↑ Perna, D.; Hromakina, T.; Merlin, F.; Ieva, S.; Fornasier, S.; Belskaya, I.; Epifani, E. Mazzotta (2017-04-21). "The very homogeneous surface of the dwarf planet Makemake". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 466 (3): 3594–3599. Bibcode:2017MNRAS.466.3594P. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw3272. ISSN 0035-8711.

- ↑ "Dwarf Planet Makemake Lacks Atmosphere". ESO Press Release. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ↑ E.L. Schaller; M.E. Brown (2007-04-10). "Volatile Loss and Retention on Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astrophysical Journal. 659 (1): L61–L64. Bibcode:2007ApJ...659L..61S. doi:10.1086/516709.

- ↑ Keeter, Bill (2016-05-04). "Pluto's Interaction with the Solar Wind is Unique, Study Finds". NASA. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ↑ Beatty, Kelly (2016-03-25). "Pluto's Atmosphere Confounds Researchers". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Parker, A. H.; Buie, M. W.; Grundy, W. M.; Noll, K. S. (2016-04-25). "Discovery of a Makemakean Moon". The Astrophysical Journal. 825: L9. arXiv:1604.07461. Bibcode:2016ApJ...825L...9P. doi:10.3847/2041-8205/825/1/L9.

- 1 2 3 "HubbleSite – NewsCenter – Hubble Discovers Moon Orbiting the Dwarf Planet Makemake (04/26/2016) – The Full Story". hubblesite.org. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (26 April 2016). "Makemake, the Moonless Dwarf Planet, Has a Moon, After All". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- 1 2 Parker, A. (2016-05-02). "A Moon for Makemake". Planetary Society blogs. Planetary Society. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- ↑ "Hubble Spies A Moon Orbiting A Distant Dwarf Planet". Popular Science. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ "Hubble discovers moon orbiting the dwarf planet Makemake". EurekAlert!. 26 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Mike Wall (26 April 2016). "Distant Dwarf Planet Makemake Has Its Own Moon". Space.com. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ↑ McGranaghan, R.; Sagan, B.; Dove, G.; Tullos, A.; Lyne, J. E.; Emery, J. P. (2011). "A Survey of Mission Opportunities to Trans-Neptunian Objects". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 64: 296–303. Bibcode:2011JBIS...64..296M.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Makemake. |

- MPEC listing for Makemake

- AstDys orbital elements

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Ephemeris

- Press release from WHT and TNG on Makemake's similarity to Pluto.

- Makemake Sky Charts and Coordinates

- Precovery image with the 1.06 m Kleť Observatory telescope on April 20, 2003

- Makemake as seen on 2010-02-18 UT with the Keck 1

- Makemake of the Outer Solar System APOD July 15, 2008

- Simulation of Makemake (2005 FY9)'s orbit

_(cropped).jpg)