Timeline of major famines in India during British rule

| Major famines in India during British rule |

|---|

|

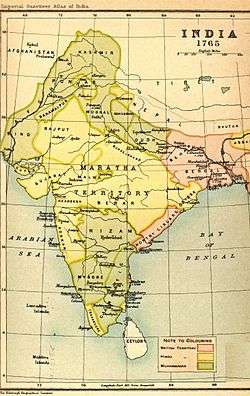

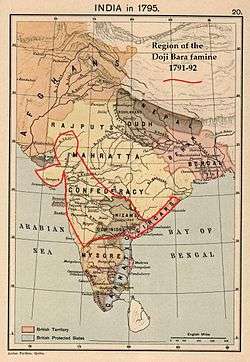

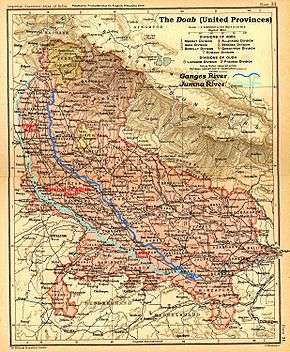

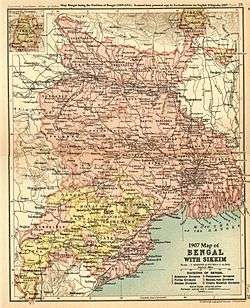

This is a timeline of major famines on the Indian subcontinent during British rule from 1765 to 1947. The famines included here occurred both in the princely states (regions administered by Indian rulers), British India (regions administered either by the British East India Company from 1765 to 1857; or by the British Crown, in the British Raj, from 1858 to 1947) and Indian territories independent of British rule such as the Maratha Empire. The total human population of British India was around 331 Million. At least 55.1 million people may have died in famines during British rule, which was around 17% of entire population. Such death toll is similar to wiping out the entire south Korean population.

The year 1765 is chosen as the start year because that year the British East India Company, after its victory in the Battle of Buxar, was granted the Diwani (rights to land revenue) in the region of Bengal (although it would not directly administer Bengal until 1784 when it was granted the Nizamat, or control of law and order.) The year 1947 is the year in which the British Raj was dissolved and the new successor states of Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan were established.

Timeline

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

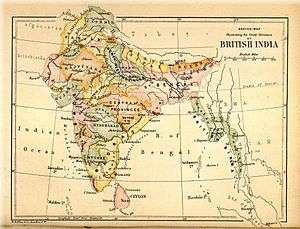

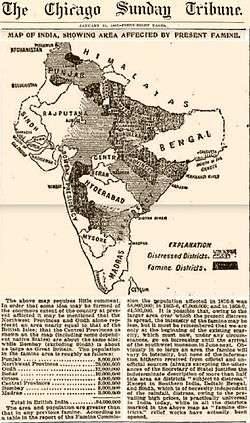

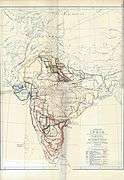

Map of famines in India between 1800 and 1878.

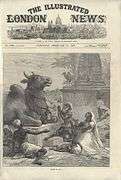

Map of famines in India between 1800 and 1878.- Engraving from The Graphic, October 1877, showing the plight of animals as well as humans in Bellary district, Madras Presidency, British India during the Great Famine of 1876–78.

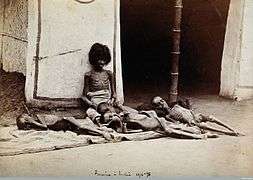

A photograph of a famine stricken mother with baby who at 3 months weighs 3 pounds. Photographer: W. W. Hooper. Great Famine of 1876–78.

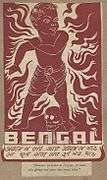

A photograph of a famine stricken mother with baby who at 3 months weighs 3 pounds. Photographer: W. W. Hooper. Great Famine of 1876–78. A poster envisioning the future of Bengal after the Bengal famine of 1943.

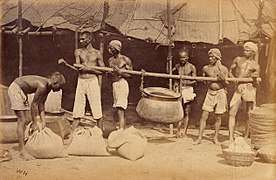

A poster envisioning the future of Bengal after the Bengal famine of 1943. Government famine relief Ahmedabad, c. 1901.

Government famine relief Ahmedabad, c. 1901. "Famine in India" front cover of Illustrated London News, February 21, 1874.

"Famine in India" front cover of Illustrated London News, February 21, 1874. Five emaciated children during the famine of 1876-78, India. Photographer: WW Hooper.

Five emaciated children during the famine of 1876-78, India. Photographer: WW Hooper. An illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing homeless people eating on the sidewalk during the Bengal famine of 1943.

An illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing homeless people eating on the sidewalk during the Bengal famine of 1943. Famine in Bengal: Grain-boats on the Ganges. Illustrated London News, March 21, 1874.

Famine in Bengal: Grain-boats on the Ganges. Illustrated London News, March 21, 1874. Drawing, titled "Famine in India," from The Graphic, February 27, 1897, showing a bazaar scene in India with shoppers, many of whom are emaciated, buying grain from a merchant's shop.

Drawing, titled "Famine in India," from The Graphic, February 27, 1897, showing a bazaar scene in India with shoppers, many of whom are emaciated, buying grain from a merchant's shop. A group of emaciated women and children in Bangalore, India, famine of 1876–78. Photographer: WW Hooper.

A group of emaciated women and children in Bangalore, India, famine of 1876–78. Photographer: WW Hooper. Illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing a starvation fatality in the Bengal famine of 1943.

Illustration from Bengal Speaks (1944) showing a starvation fatality in the Bengal famine of 1943. Famine relief at Bellary, Madras Presidency, The Graphic, October 1877.

Famine relief at Bellary, Madras Presidency, The Graphic, October 1877.- Engraving from The Graphic, October 1877, showing two forsaken children in the Bellary district of the Madras Presidency during the famine.

Famine tokens of 1874 Bihar famine, and the 1876 Great famine.

Famine tokens of 1874 Bihar famine, and the 1876 Great famine. The "Cooks' Room" at a famine relief camp, Madras Presidency, 1876–78. Phtographer: W. W. Hooper.

The "Cooks' Room" at a famine relief camp, Madras Presidency, 1876–78. Phtographer: W. W. Hooper. Cartoon from Punch, "Mending the Lesson" showing Miss Prudence warning John Bull about handing out too much charity to the needy during the Bihar famine of 1873-74, and the latter's own interpretation of the Law of Supply and Demand.

Cartoon from Punch, "Mending the Lesson" showing Miss Prudence warning John Bull about handing out too much charity to the needy during the Bihar famine of 1873-74, and the latter's own interpretation of the Law of Supply and Demand. Victims of the Great Famine of 1876–78 in British India, pictured in 1877. The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The death toll from this famine is estimated to be in the range of 5.5 million people.[8]

Victims of the Great Famine of 1876–78 in British India, pictured in 1877. The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totalling 58,500,000. The death toll from this famine is estimated to be in the range of 5.5 million people.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to a 1901 estimate published in The Lancet, this and other famines in India between 1891 to 1901 caused 19,000,000 deaths from "starvation or to the diseases arising therefrom",[12] an estimate criticised by the writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn.[13]

- ↑ According to a 1901 estimate published in The Lancet, this and other famines in India between 1891 to 1901 caused 19,000,000 deaths from "starvation or to the diseases arising therefrom",[12] an estimate criticised by the writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn.[13]

Citations

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume III 1907, pp. 501–502

- ↑ Cambridge 1983, p. 528

- ↑ Cambridge 1983, p. 299

- ↑ Grove 2007, p. 80

- ↑ Grove 2007, p. 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fieldhouse 1996, p. 132

- ↑ Cambridge 1983, p. 529

- 1 2 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 488

- ↑ Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 4

- ↑ Davis 2001, p. 7

- 1 2 C.A.H. Townsend, Final repor of thirds revised revenue settlement of Hisar district from 1905-1910, Gazetteer of Department of Revenue and Disaster Management, Haryana, point 22, page 11.

- 1 2 The effect of famines on the population of India, The Lancet, Vol. 157, No. 4059, June 15, 1901, pp. 1713-1714;

Sven Beckert (2015). Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Random House. p. 337. ISBN 978-0-375-71396-5. ;

Davis, Mike (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso. p. 7. ISBN 978-1859847398. - 1 2 C.W. McMinn, Famine Truths, Half Truths, Untruths (Calcutta: 1902), p.87; According to the writer and retired Indian Civil Servant Charles McMinn, The Lancet's estimates were an overestimate based on a mistake in the population changes in India from 1891-1901. The Lancet, states McMinn, declared that the population increased only by 2.8 million for the whole of India, while the actual increase was 7.5 million according to him. The Lancet source, contrary to McMinn claims, states that the population increased from 287,317,048 to 294,266,702 (2.42%). Adjusting for changes in census tracts, the total population increase in India was only 1.49% between 1891 and 1901, a major decline from the decadal change of 11.2% observed between 1881 and 1891, according to The Lancet article in April 13, 1901. It attributes the decrease in population change rate to excess mortality from successive famines and the plague. See: The Census in India, The Lancet, Vol. 157, No. 4050, pp. 1107–1108

- ↑ Cambridge 1983, p. 531.

References

Famines

- Arun Agrawal (2013), "Food Security and Sociopolitical Stability in South Asia", in Christopher B. Barret, Food Security and Sociopolitical Stability, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 406–427, ISBN 978-0-19-166870-8

- Appadurai, Arjun (1984), "How Moral Is South Asia's Economy?—A Review of Rural Society in Southeast India. by Kathleen Gough; Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The Famine of 1943-1944. by Paul R. Greenough; Subject to Famine: Food Crises and Economic Change in Western India, 1860- 1920. by Michelle B. McAlpin; Why They Did Not Starve: Biocultural Adaptation in a South Indian Village. by Morgan D. Maclachlan; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. by Amartya Sen" (PDF), The Journal of Asian Studies, 43 (3): 481–497, doi:10.2307/2055760

- Ambirajan, S. (1976), "Malthusian Population Theory and Indian Famine Policy in the Nineteenth Century", Population Studies, 30 (1): 5–14, doi:10.2307/2173660

- Arnold, David (2013), "Hunger in the Garden of Plenty: The Bengal Famine of 1770", in Alessa Johns, Dreadful Visitations: Confronting Natural Catastrophe in the Age of Enlightenment, Taylor & Francis, pp. 81–112, ISBN 978-1-136-68396-1

- Arnold, David (1994), "The 'discovery' of malnutrition and diet in colonial India", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 31 (1): 1–26, doi:10.1177/001946469403100101

- Arnold, David; Moore, R. I. (1991), Famine: Social Crisis and Historical Change (New Perspectives on the Past), Wiley-Blackwell. Pp. 164, ISBN 0-631-15119-2

- Attwood, Donald W. (2005), "Big Is Ugly? How Large-scale Institutions Prevent Famines in Western India", World Development, 33 (12): 2067–2083, doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.009

- Banik, Dan (2007), Starvation and India’s Democracy, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-13416-8

- Bayly, C. A. (2002), Rulers, Townsmen, and Bazaars: North Indian Society in the Age of British Expansion 1770–1870, Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. 530, ISBN 0-19-566345-4

- Bhatia, B. M. (1991), Famines in India: A Study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India With Special Reference to Food Problem, 1860–1990, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division. Pp. 383, ISBN 81-220-0211-0

- Bouma, Menno J.; van der Kay, Hugo J. (1996), "The El Niño Southern Oscillation and the historic malaria epidemics on the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka: an early warning system for future epidemics", Tropical Medicine and International Health, 1 (1): 86–96, doi:10.1046/j.1365-3156.1996.d01-7.x

- The Cambridge economic history of India, Volume 2, Cambridge University Press, 1983, ISBN 978-0-521-22802-2

- Chamberlain, Andrew T. (2006), Demography in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-139-45534-3

- Charlesworth, Neil (2002), Peasants and Imperial Rule: Agriculture and Agrarian Society in the Bombay Presidency 1850-1935, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52640-1

- Damodaran, Vinita (2007), "Famine in Bengal: A Comparison of the 1770 Famine in Bengal and the 1897 Famine in Chotanagpur", The Medieval History Journal, 10 (1&2): 143–181, doi:10.1177/097194580701000206

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts, Verso Books, ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- Drèze, Jean (1995), "Famine prevention in India", in Drèze, Jean; Sen, Amartya; Hussain, Althar, The political economy of hunger: Selected essays, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. 644, ISBN 0-19-828883-2

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2005) [1900], Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd (reprinted by Adamant Media Corporation), ISBN 1-4021-5115-2

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part I", Population Studies, Taylor & Francis, 45 (1): 5–25, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145056, JSTOR 2174991

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part II", Population Studies, Taylor & Francis, 45 (2): 279–297, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145446, JSTOR 2174784

- Dyson, Tim, ed. (1989), India's Historical Demography: Studies in Famine, Disease and Society, Riverdale MD: The Riverdale Company. Pp. ix, 296

- Fagan, Brian (2009), Floods, Famines, and Emperors: El Nino and the Fate of Civilizations, Basic Books. Pp. 368, ISBN 0-465-00530-6

- Famine Commission (1880), Report of the Indian Famine Commission, Part I, Calcutta

- Fieldhouse, David (1996), "For Richer, for Poorer?", in Marshall, P. J., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 400, pp. 108–146, ISBN 0-521-00254-0

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389

- Gilbert, Martin (2003), The Routledge Atlas of British History, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-28147-8

- Government of India (1867), Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Enquire into the Famine in Bengal and Orissa in 1866, Volumes I, II, Calcutta

- O Grada, Cormac (1997), "Markets and famines: A simple test with Indian data", Economic Letters, 57: 241–244, doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(97)00228-0

- Greenough, Paul Robert (1982), Prosperity and Misery in Modern Bengal: The Famine of 1943-1944, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-503082-2

- Grove, Richard H. (2007), "The Great El Nino of 1789–93 and its Global Consequences: Reconstructing an Extreme Climate Even in World Environmental History", The Medieval History Journal, 10 (1&2): 75–98, doi:10.1177/097194580701000203

- Hall-Matthews, David (2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 42 (1): 1–24, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07002892

- Hall-Matthews, David (1996), "Historical Roots of Famine Relief Paradigms: Ideas on Dependency and Free Trade in India in the 1870s", Disasters, 20 (3): 216–230, doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1996.tb01035.x

- Hardiman, David (1996), "Usuary, Dearth and Famine in Western India", Past and Present, 152: 113–156, doi:10.1093/past/152.1.113

- Hill, Christopher V. (1991), "Philosophy and Reality in Riparian South Asia: British Famine Policy and Migration in Colonial North India", Modern Asian Studies, 25 (2): 263–279, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00010672

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502), Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Kaiwar, Vasant (2016), "Famines of structural adjustment in colonial India", in Kaminsky, Arnold P; Long, Roger D, Nationalism and Imperialism in South and Southeast Asia: Essays Presented to Damodar R.SarDesai, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-351-99742-3

- Keim, Mark E. (2015), "Extreme Weather Events: The Role of Public Health in Disaster Risk Reduction as a Means for Climate Change Adaptation", in George Luber; Jay Lemery, Global Climate Change and Human Health: From Science to Practice, Wiley, p. 42, ISBN 978-1-118-60358-1

- Klein, Ira (August 1973), "Death in India, 1871-1921", The Journal of Asian Studies, Association for Asian Studies, 32 (4): 639–659, doi:10.2307/2052814, JSTOR 2052814

- Maclachlan, Morgan D. (1983), Why They Did Not Starve: Biocultural Adaptation in a South Indian Village, Institute for the Study of Human Issues, ISBN 978-0-89727-001-4

- Maharatna, Arup (1996), The demography of famines: an Indian historical perspective, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563711-3

- McAlpin, Michelle Burge (2014), Subject to Famine: Food Crisis and Economic Change in Western India, 1860-1920, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-5592-6

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (Autumn 1983), "Famines, Epidemics, and Population Growth: The Case of India", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, The MIT Press, 14 (2): 351–366, doi:10.2307/203709, JSTOR 203709

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1979), "Dearth, Famine, and Risk: The Changing Impact of Crop Failures in Western India, 1870–1920", The Journal of Economic History, 39 (1): 143–157, doi:10.1017/S0022050700096352

- McGregor, Pat; Cantley, Ian (1992), "A Test of Sen's Entitlement Hypothesis", The Statistician, 41 (3 Special Issue: Conference on Applied Statistics in Ireland, 1991): 335–341, JSTOR 2348558

- Mellor, John W.; Gavian, Sarah (1987), "Famine: Causes, Prevention, and Relief", Science, New Series, 235 (4788): 539–545, doi:10.1126/science.235.4788.539, JSTOR 1698676

- Muller, W. (1897), "Notes on the Distress Amongst the Hand-Weavers in the Bombay Presidency During the Famine of 1896–97", The Economic Journal, 7 (26): 285–288, doi:10.2307/2957261, JSTOR 2957261

- Nisbet, John (1901), Burma Under British Rule - and Before, II, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co. Ltd

- Owen, Nicholas (2008), The British Left and India: Metropolitan Anti-Imperialism, 1885–1947 (Oxford Historical Monographs), Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pp. 300, ISBN 0-19-923301-2

- Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India, 1857–1947, 2nd edition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. xvi, 385, ISBN 0-19-568430-3

- Roy, Tirthankar (June 2016), Were Indian famines 'natural' or 'man-made'?, London School of Economics, Economic History, Working Papers No: 243/2016

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Seavoy, Ronald E. (1986), Famine in Peasant Societies, London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 978-0-313-25130-6

- Sen, A. K. (1977), "Starvation and Exchange Entitlements: A General Approach and its Application to the Great Bengal Famine", Cambridge Journal of Economics

- Sen, A. K. (1982), Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Pp. ix, 257, ISBN 0-19-828463-2

- Sharma, Sanjay (1993), "The 1837–38 famine in U.P.: Some dimensions of popular action", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 30 (3): 337–372, doi:10.1177/001946469303000304

- Siddiqi, Asiya (1973), Agrarian Change in a Northern Indian State: Uttar Pradesh, 1819–1833, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. Pp. 222, ISBN 0-19-821553-3

- Stokes, Eric (1975), "Agrarian Society and the Pax Britannica in Northern India in the Early Nineteenth Century", Modern Asian Studies, 9 (4): 505–528, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00012877, JSTOR 312079

- Stone, Ian, Canal Irrigation in British India: Perspectives on Technological Change in a Peasant Economy (Cambridge South Asian Studies), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 389, ISBN 0-521-52663-9

- Tomlinson, B. R. (1993), The Economy of Modern India, 1860–1970 (The New Cambridge History of India, III.3), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press., ISBN 0-521-58939-8

- Washbrook, David (1994), "The Commercialization of Agriculture in Colonial India: Production, Subsistence and Reproduction in the 'Dry South', c. 1870–1930", Modern Asian Studies, 28 (1): 129–164, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011720, JSTOR 312924

- Yang, Anand A. (1998), Bazaar India: Markets, Society, and the Colonial State in Bihar, Berkeley: University of California Press

Epidemics and Public Health

- Banthia, Jayant; Dyson, Tim (December 1999), "Smallpox in Nineteenth-Century India", Population and Development Review, Population Council, 25 (4): 649–689, doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00649.x, JSTOR 172481

- Caldwell, John C. (December 1998), "Malthus and the Less Developed World: The Pivotal Role of India", Population and Development Review, Population Council, 24 (4): 675–696, doi:10.2307/2808021, JSTOR 2808021

- Drayton, Richard (2001), "Science, Medicine, and the British Empire", in Winks, Robin, Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 264–276, ISBN 0-19-924680-7

- Derbyshire, I. D. (1987), "Economic Change and the Railways in North India, 1860-1914", Population Studies, 21 (3): 521–545, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00009197

- Klein, Ira (1988), "Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India", Modern Asian Studies, Cambridge University Press, 22 (4): 723–755, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00015729, JSTOR 312523

- Watts, Sheldon (1999), "British Development Policies and Malaria in India 1897-c. 1929", Past and Present (165): 141–181, doi:10.2307/651287

- Wylie, Diana (2001), "Disease, Diet, and Gender: Late Twentieth Century Perspectives on Empire", in Winks, Robin, Oxford History of the British Empire: Historiography, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 277–289, ISBN 0-19-924680-7