Great Famine of 1876–78

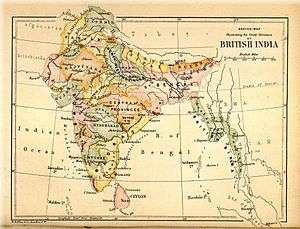

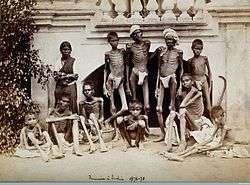

The Great Famine of 1876–78 (also the Southern India famine of 1876–78 or the Madras famine of 1877) was a famine in India under the British Raj. It began in 1876 after an intense drought resulting in crop failure in the Deccan Plateau.[1] It affected south and southwestern India (Madras, Mysore, Hyderabad, and Bombay) for a period of two years. In its second year famine also spread north to some regions of the Central Provinces and the North-Western Provinces, and to a small area in the Punjab.[2] The famine ultimately covered an area of 670,000 square kilometres (257,000 sq mi) and caused distress to a population totaling 58,500,000.[2] The death toll from this famine is estimated to be in the range of 5.5 million people.[3] British economic policies played a substantial role in exporting grain out of India and otherwise exacerbating the famine's mortality.

In his acclaimed book Late Victorian Holocausts, Mike Davis called the famine a "colonial genocide" perpetrated by Great Britain. Some, including Niall Ferguson, dispute this judgment, while others, including Adam Jones, affirm it.[4][5]

Preceding events

In part, the Great Famine may have been caused by an intense drought resulting in crop failure in the Deccan Plateau.[1] But, the regular export of grain by the colonial government; during the famine the viceroy, Lord Lytton, oversaw the export to England of a record 6.4 million hundredweight (320,000 ton) of wheat, made the region more vulnerable. However, the cultivation of alternate cash crops, in addition to the commodification of grain, played a significant role in the events.[6][7]

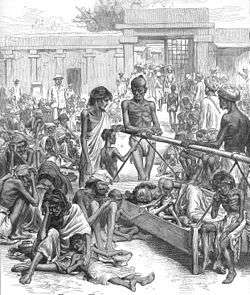

The famine occurred at a time when the colonial government was attempting to reduce expenses on welfare. Earlier, in the Bihar famine of 1873–74, severe mortality had been avoided by importing rice from Burma. However, the Government of Bengal and its Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Richard Temple, were criticized for excessive expenditure on charitable relief.[8] Sensitive to any renewed accusations of excess in 1876, Temple, who was now Famine Commissioner for the Government of India,[2] insisted not only on a policy of laissez faire with respect to the trade in grain,[9] but also on stricter standards of qualification for relief and on more meager relief rations.[2] Two kinds of relief were offered: "relief works" for able-bodied men, women, and working children, and gratuitous (or charitable) relief for small children, the elderly, and the indigent.[10]

Famine and relief

The insistence on more rigorous tests for qualification, however, led to strikes by "relief workers" in the Bombay presidency.[2] Furthermore, in January 1877, Temple reduced the wage for a day's hard work in the relief camps in Madras and Bombay[11]—this 'Temple wage' consisted of 450 grams (1 lb) of grain plus one anna for a man, and a slightly reduced amount for a woman or working child,[12] for a "long day of hard labour without shade or rest."[13] The rationale behind the reduced wage, which was in keeping with a prevailing belief of the time, was that any excessive payment might create 'dependency' (or "demoralization" in contemporaneous usage) among the famine-afflicted population.[11]

Temple's recommendations were opposed by a number of officials, including William Digby and the physician W. R. Cornish, Sanitary Commissioner for the Madras Presidency.[14] Cornish argued for a minimum of 680 grams (1.5 lb) of grain and, in addition, supplements of vegetables and protein, especially if the individuals were performing strenuous labor in the relief works.[14] However, Lytton supported Temple, who argued that "everything must be subordinated to the financial consideration of disbursing the smallest sum of money."[15]

Eventually, in March 1877, the provincial government of Madras, increased the ration halfway towards Cornish's recommendations, to 570 grams (1.25 lb) of grain and 43 grams (1.5 oz) of protein in the form of daal (pulses).[14] Meanwhile, many more people had succumbed to the famine.[16] In other parts of India, such as the United Provinces, where relief was meager, the resulting mortality was high.[16] In the autumn and winter of 1878, an epidemic of malaria killed many more who were already weakened by malnutrition.[16]

By early 1877, Temple proclaimed that he had put "the famine under control." Digby noted that "a famine can scarcely be said to be adequately controlled which leaves one-fourth of the people dead."[15]

All in all, the Government of India spent Rs. 8 1/30 million in relieving 700 million units (1 unit = relief for 1 person for 1 day) in British India and, in addition, another Rs. 7.2 million in relieving 72 million units in the princely states of Mysore and Hyderabad.[16] Revenue (tax) payments to the amount of Rs. 6 million were either not enforced or postponed until the following year, and charitable donations from Great Britain and the colonies totaled Rs. 8.4 million.[16] However, this cost was minuscule per capita; for example, the expenditure incurred in the Bombay Presidency was less than one-fifth of that in the Bihar famine of 1873–74, which affected a smaller area and did not last as long.[13]

Famine in Mysore State

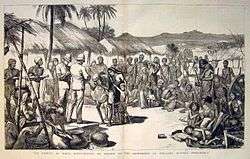

Two years before the famine of 1876, heavy rain destroyed ragi crops in Kolar and Bangalore. Scant rainfall the following year resulted in drying up of lakes, affecting food stock. As a result of the famine, the population of the state decreased by 874,000 (in comparison with the 1871 census).

Sir Richard Temple was sent by the British India Government as Special Famine Commissioner to oversee the relief works of the Mysore government. To deal with the famine, the government of Mysore, started relief kitchens. A large number of people came into Bangalore, when relief was available. These people had to work on the Bangalore-Mysore railway line in exchange for food and grains. The Mysore government imported large quantities of grain from the neighbouring British ruled Madras Presidency. Grazing in forests was allowed temporarily, and new tanks were constructed and old tanks repaired. The Dewan of Mysore State, C. V. Rungacharlu, in his Dasara speech estimated the cost to the state at 160 lakhs, with the state incurring a debt of 80 lakhs.[17]

Aftermath

The mortality in the famine was in the range of 5.5 million people.[3] The excessive mortality and the renewed questions of "relief and protection" that were asked in its wake, led directly to the constituting of the Famine Commission of 1880 and to the eventual adoption of the Provisional Famine Code in British India.[16] After the famine, a large number of agricultural laborers and handloom weavers in South India emigrated to British tropical colonies to work as indentured laborers in plantations.[18] The excessive mortality in the famine also neutralized the natural population growth in the Bombay and Madras presidencies during the decade between the first and second censuses of British India in 1871 and 1881 respectively.[19] The famine lives on in the Tamil and other literary traditions.[20] A large number of Kummi folk songs describing this famine have been documented.[21]

The Great Famine was to have a lasting political impact on events in India. Among the British administrators in India who were unsettled by the official reactions to the famine and, in particular by the stifling of the official debate about the best form of famine relief, were William Wedderburn and A. O. Hume.[22] Less than a decade later, they would found the Indian National Congress and, in turn, influence a generation of Indian nationalists. Among the latter were Dadabhai Naoroji and Romesh Chunder Dutt for whom the Great Famine would become a cornerstone of the economic critique of the British Raj.[22]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Roy 2006, p. 361

- 1 2 3 4 5 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 488

- 1 2 Fieldhouse 1996, p. 132 Quote: "In the later nineteenth century there was a series of disastrous crop failures in India leading not only to starvation but to epidemics. Most were regional, but the death toll could be huge. Thus, to take only some of the worst famines for which the death rate is known, some 800,000 died in the North West Provinces, Punjab, and Rajasthan in 1837–38; perhaps 2 million in the same region in 1860–61; nearly a million in different areas in 1866–67; 4.3 million in widely spread areas in 1876–78, an additional 1.2 million in the North West Provinces and Kashmir in 1877–78; and, worst of all, over 5 million in a famine that affected a large population of India in 1896–97. In 1899–1900 more than a million were thought to have died, conditions being worse because of the shortage of food following the famines only two years earlier. Thereafter the only major loss of life through famine was in 1943 under exceptional wartime conditions.(p. 132)"

- ↑ Jones, Adam (2016-12-16). "Chapter 2: State and Empire". Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781317533856.

- ↑ Powell, Christopher (2011-06-15). Barbaric Civilization: A Critical Sociology of Genocide. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 238–245. ISBN 9780773585560.

- ↑ S. Guha, Environment and Ethnicity in India, 1200-1991 2006. p.116

- ↑ Mike Davis, 2001. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nino Famines and the Making of the Third World. Verso, London.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 488, Hall-Matthews 1996, pp. 217–219

- ↑ Hall-Matthews 1996, p. 217

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, pp. 477–483

- 1 2 Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 5

- ↑ Washbrook 1994, p. 145, Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 489

- 1 2 Hall-Matthews 1996, p. 219

- 1 2 3 Arnold 1994, pp. 7–8

- 1 2 Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso, 2001; calories for Buchenwald diet: 1750; Temple wage: 1627. Both involved hard labour (p.39); Temple's remark on financial considerations p.40

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III 1907, p. 489

- ↑ Prasad, S Narendra (5 August 2014). "A devastating famine" (Bangalore). Deccan Herald. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ↑ Roy 2006, p. 362

- ↑ Roy 2006, p. 363

- ↑ .....panchalakshna tirumugavilasam , a satire published in 1899, composed by Villiappa Pillai, one of the court poets of Sivagangai. This narrative piece full of humour and biting irony deals in ca.4500 lines with the conditions of the people suffering in the great famine of 1876... God Sunderesvara of Madurai pleads his helplessness in solving the problems of inhabitants hit by the famine..Kamil Zvelebil (1974). Tamil Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 218–. ISBN 978-3-447-01582-0. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ↑ "இந்தவாரம் கலாரசிகன்". Dina Mani (in Tamil). 20 June 2010. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- 1 2 Hall-Matthews 2008, p. 24

References

- Arnold, David (1994), "The 'discovery' of malnutrition and diet in colonial India", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 31 (1): 1–26, doi:10.1177/001946469403100101

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts, Verso Books. Pp. 400, ISBN 978-1-85984-739-8

- Fieldhouse, David (1996), "For Richer, for Poorer?", in Marshall, P. J., The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pp. 400, pp. 108–146, ISBN 0-521-00254-0

- Hall-Matthews, David (1996), "Historical Roots of Famine Relief Paradigms: Ideas on Dependency and Free Trade in India in the 1870s", Disasters, 20 (3): 216–230, doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.1996.tb01035.x

- Hall-Matthews, David (2008), "Inaccurate Conceptions: Disputed Measures of Nutritional Needs and Famine Deaths in Colonial India", Modern Asian Studies, 42 (1): 1–24, doi:10.1017/S0026749X07002892

- Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. III (1907), The Indian Empire, Economic (Chapter X: Famine, pp. 475–502, Published under the authority of His Majesty's Secretary of State for India in Council, Oxford at the Clarendon Press. Pp. xxx, 1 map, 552.

- Roy, Tirthankar (2006), The Economic History of India, 1857–1947, 2nd edition, New Delhi: Oxford University Press. Pp. xvi, 385, ISBN 0-19-568430-3

- Washbrook, David (1994), "The Commercialization of Agriculture in Colonial India: Production, Subsistence and Reproduction in the 'Dry South', c. 1870–1930", Modern Asian Studies, 28 (1): 129–164, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00011720, JSTOR 312924

Further reading

- FAHEEM, S. (1976), "Malthusian Population Theory and Indian Famine Policy in the Nineteenth Century", Population Studies, 30 (1): 5–14, doi:10.2307/2173660

- Bhatia, B. M. (1991), Famines in India: A Study in Some Aspects of the Economic History of India With Special Reference to Food Problem, 1860–1990, Stosius Inc/Advent Books Division. Pp. 383, ISBN 81-220-0211-0

- Davis, Mike (2001), Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World, Verso. Pp. 464, ISBN 1-85984-739-0

- Digby, William (1878), The Famine Campaign in Southern India: Madras and Bombay Presidencies and province of Mysore, 1876-1878, Volume 1, London: Longmans, Green and Co

- Digby, William (1878), The Famine Campaign in Southern India: Madras and Bombay Presidencies and province of Mysore, 1876-1878, Volume 2, London: Longmans, Green and Co

- Dutt, Romesh Chunder (2005) [1900], Open Letters to Lord Curzon on Famines and Land Assessments in India, London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Ltd (reprinted by Adamant Media Corporation), ISBN 1-4021-5115-2

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part I", Population Studies, 45 (1): 5–25, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145056, JSTOR 2174991

- Dyson, Tim (1991), "On the Demography of South Asian Famines: Part II", Population Studies, 45 (2): 279–297, doi:10.1080/0032472031000145446, JSTOR 2174784

- Famine Commission (1880), Report of the Indian Famine Commission, Part I, Calcutta

- Ghose, Ajit Kumar (1982), "Food Supply and Starvation: A Study of Famines with Reference to the Indian Subcontinent", Oxford Economic Papers, New Series, 34 (2): 368–389

- Government of India (1867), Report of the Commissioners Appointed to Enquire into the Famine in Bengal and Orissa in 1866, Volumes I, II, Calcutta

- Hardiman, David (1996), "Usuary, Dearth and Famine in Western India", Past and Present, 152: 113–156, doi:10.1093/past/152.1.113

- Hill, Christopher V. (1991), "Philosophy and Reality in Riparian South Asia: British Famine Policy and Migration in Colonial North India", Modern Asian Studies, 25 (2): 263–279, doi:10.1017/s0026749x00010672

- Klein, Ira (1973), "Death in India, 1871-1921", The Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (4): 639–659, doi:10.2307/2052814

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1983), "Famines, Epidemics, and Population Growth: The Case of India", Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 14 (2): 351–366, doi:10.2307/203709

- McAlpin, Michelle B. (1979), "Dearth, Famine, and Risk: The Changing Impact of Crop Failures in Western India, 1870–1920", The Journal of Economic History, 39 (1): 143–157, doi:10.1017/S0022050700096352

- Temple, Sir Richard (1882), Men and events of my time in India, London: John Murray. Pp. xvii, 526