The Amazing Race (U.S. TV series)

| The Amazing Race | |

|---|---|

| |

| Genre | Reality competition |

| Created by |

Elise Doganieri Bertram van Munster |

| Presented by | Phil Keoghan |

| Theme music composer | John M. Keane |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| No. of seasons | 30 |

| No. of episodes | 353 |

| Production | |

| Executive producer(s) |

Jerry Bruckheimer Bertram van Munster Jonathan Littman Elise Doganieri Mark Vertullo |

| Production location(s) | See below |

| Camera setup | Multi-camera |

| Running time | 43 minutes |

| Production company(s) |

Jerry Bruckheimer Television Worldrace Productions Amazing Race Productions CBS Television Studios Touchstone Television (2001–2007) ABC Studios (2007–present) |

| Distributor |

CBS Television Distribution (U.S.) Disney Media Distribution (International) |

| Release | |

| Original network | CBS |

| Picture format |

480i (4:3 SDTV) (2001–10) 1080i (16:9 HDTV) (2011–present) |

| Original release | September 5, 2001 – present |

| Chronology | |

| Related shows | International versions |

| External links | |

| Website | |

The Amazing Race is an American reality competition show in which typically eleven teams of two race around the world. The race is generally split into twelve legs, with each leg requiring teams to deduce clues, navigate themselves in foreign areas, interact with locals, perform physical and mental challenges, and vie for airplane, boat, taxi, and other public transportation options on a limited budget provided by the show. Teams are progressively eliminated at the end of most legs, while the first team to arrive at the end of the final leg wins the grand prize of US$1 million. As the original version of the Amazing Race franchise, the CBS program has been running since 2001. Numerous international versions have been developed following the same core structure, while the U.S. version is also broadcast to several other markets. The most recent season, the show's 30th, premiered on January 3, 2018, and aired over eight weeks.[1][2] The show has been renewed for a 31st season to debut during the 2018–19 television season.[3]

The show was created by Elise Doganieri and Bertram van Munster, who, along with Jonathan Littman, serve as executive producers. The show is produced by Earthview Inc. (headed by Doganieri and van Munster), Jerry Bruckheimer Television for CBS Television Studios and ABC Studios (a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company). The series has been hosted by veteran New Zealand television personality Phil Keoghan since its inception.

Since the inception of the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Reality-Competition Program in 2003, The Amazing Race has won it ten out of fourteen times; the show has also won other awards and commendations. Although it has moved around several prime time slots since its inception, the program has averaged about 10 million viewers per season.[4]

Premise

The Amazing Race is a reality television competition, typically involving eleven teams of two, in a race around the world. The race cycle is divided into a number of legs, normally twelve; each episode generally covers the events of one leg. Each leg ends with a Pit Stop, where teams are given a chance to rest and recover before starting the next leg twelve hours later. The first team to arrive at a Pit Stop is often awarded a prize such as a trip, while the last team is normally eliminated from the race. Some legs are non-elimination legs, where the last team to arrive may be penalized in the following leg. Some races have featured double-length legs, where the teams meet the host at what appears to be a Pit Stop, only to be told to continue to race. The final leg of each race is run by the last three remaining teams, and the first to arrive at the final destination wins the show's prize, US$1 million. The average length of each race is approximately 25 to 30 days.

During each leg, teams follow clues from Route Markers—boxes containing clue envelopes marked in the race's red, yellow, and white colors—to determine their next destination. Travel between destinations includes commercial and chartered airplanes, boats, trains, taxis, buses, and rented vehicles provided by the show, or the teams may simply travel by foot. Teams are required to pay for all expenses while traveling from a small stipend (on the order of $100) given to them at the start of each leg. Any money left unspent can be used in future legs of the race. The only exception is air travel, where teams are given a credit card to purchase economy-class fares. Some teams have resorted to begging to replenish their funds.[5]

Clues may directly identify locations, contain cryptic riddles such as "Travel to the westernmost point in continental Europe" that teams must figure out, or include physical elements, such as a country flag, indicating their next destination. Clues may also describe a number of tasks that teams must complete before continuing to race. As such, teams are generally free and sometimes required to engage locals to help in any manner to decipher clues and complete tasks. Tasks are typically designed to highlight the local culture of the country they are in.[6] Such tasks include:

- Route Info: A general clue that may include a task to be completed by the team before they can receive their next clue.

- Detours: A choice of two tasks. Teams are free to choose either task or swap tasks if they find one option too difficult. There is generally one Detour present on each leg of the race.

- Roadblocks: A task only one team member can complete. Teams must choose which member will complete the task based on a brief clue about the task before fully revealing the details of the task. Later editions of the program have limits on the number of Roadblocks one team member can perform, that both team members perform the same amount. There is generally one Roadblock present on each leg of the race.

- Fast Forwards: A task that only one team may complete, allowing that team to skip all remaining tasks and head directly for the next Pit Stop. Teams may only claim one Fast Forward during the entire race. Several seasons have not featured any Fast Forwards, but it is not known if they were simply not shown on air or not included in the race.

- Intersections: Tasks that require two teams to work together until otherwise instructed. While Intersected, teams may be required to perform Detours, Roadblocks (a two-person task using one person from each team), and Fast Forwards together.

- Yields: A station where a team can force another trailing team to wait a predetermined amount of time before continuing the race. Teams may only yield any other team once per race. The Yield was last used in season 11 and has since been supplanted by the U-Turn.

- U-Turns: A station, located after a Detour, where a team can force another trailing team to return and complete the other option of the Detour they did not select. Teams may only U-Turn any other team once per race. In season 29, U-Turn stations were moved before the Detour, and the limitation on the number of U-Turns a team could use was lifted.

- Speed Bumps: A task that only the team that is saved from elimination on the previous leg must complete before continuing on the race. This usually consists of a small, easy to complete task.

- Switchbacks: A task that is based on an iconic task performed on an earlier season of the Race, typically at the same location that was previously used. Examples have been a Roadblock that held a team back for several hours leading to their elimination and a Fast Forward that presented a difficult choice but the team who took it ultimately won the race.

Teams are penalized for failing to complete these tasks as instructed or other rules of the race, generally thirty minutes plus any time gained for the infraction. Such penalties may be enforced while teams are racing, when they arrive at the Pit Stop, or at the start of the next leg.

The events of the race are generally edited and shown in chronological order, cutting between the actions of each team as they progress. More recent seasons have been edited to show split-screen footage of simultaneous actions or two or more different teams in the style of 24.[7] Footage from the race is interspersed with commentary from the individual teams or members recorded after each leg to give more insight on the events being shown.[6] The show helps to track the progress of racers through a leg by providing frequent on-screen information identifying teams and their placement.[8]

Series overview

| Season | Start line date | Finish line date | Season premiere | Season finale | Winners | Teams | Legs | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | March 8, 2001 | April 8, 2001 | September 5, 2001 | December 13, 2001 | Rob Frisbee & Brennan Swain |

11 | 13 | First documented running of the Race |

| 2 | January 7, 2002 | February 3, 2002 | March 11, 2002 | May 15, 2002 | Chris Luca & Alex Boylan |

|||

| 3 | August 9, 2002 | September 7, 2002 | October 2, 2002 | December 18, 2002 | Flo Pesenti & Zach Behr |

12 | ||

| 4 | January 18, 2003 | February 14, 2003 | May 29, 2003 | August 21, 2003 | Reichen Lehmkuhl & Chip Arndt |

|||

| 5 | January 30, 2004 | February 27, 2004 | July 6, 2004 | September 21, 2004 | Chip & Kim McAllister | 11 | Introduced the Yield and non-elimination penalty | |

| 6 | August 13, 2004 | September 12, 2004 | November 16, 2004 | February 8, 2005 | Freddy Holliday & Kendra Bentley |

12 | Introduced the double-length leg | |

| 7 | November 20, 2004 | December 19, 2004 | March 1, 2005 | May 10, 2005 | Uchenna & Joyce Agu | |||

| 8 | July 7, 2005 | July 31, 2005 | September 27, 2005 | December 13, 2005 | Nick, Alex, Megan, & Tommy Linz |

10 | 11 | Family Edition Featured family teams of four, including children as young as 8 years old |

| 9 | November 7, 2005 | December 3, 2005 | February 28, 2006 | May 17, 2006 | B. J. Averell & Tyler MacNiven |

11 | 12 | |

| 10 | May 27, 2006 | June 24, 2006 | September 17, 2006 | December 10, 2006 | Tyler Denk & James Branaman |

12 | Introduced the Intersection | |

| 11 | November 20, 2006 | December 17, 2006 | February 18, 2007 | May 6, 2007 | Eric Sanchez & Danielle Turner |

11 | 13 | All-Stars Featured returning favorite teams, and a new team that began dating after their first season |

| 12 | July 8, 2007 | July 29, 2007 | November 4, 2007 | January 20, 2008 | TK Erwin & Rachel Rosales |

11 | Introduced the U-Turn and Speed Bump | |

| 13 | April 22, 2008 | May 14, 2008 | September 28, 2008 | December 7, 2008 | Nick & Starr Spangler | |||

| 14 | October 31, 2008 | November 21, 2008 | February 15, 2009 | May 10, 2009 | Tammy & Victor Jih | Introduced the Blind U-Turn | ||

| 15 | July 18, 2009 | August 7, 2009 | September 27, 2009 | December 6, 2009 | Meghan Rickey & Cheyne Whitney |

12 | 12 | Introduced the Switchback, and start line elimination |

| 16 | November 28, 2009 | December 20, 2009 | February 14, 2010 | May 9, 2010 | Dan & Jordan Pious | 11 | ||

| 17 | May 26, 2010 | June 15, 2010 | September 26, 2010 | December 12, 2010 | Nat Strand & Kat Chang | Introduced the Express Pass and Double U-Turn | ||

| 18 | November 20, 2010 | December 12, 2010 | February 20, 2011 | May 8, 2011 | Kisha & Jen Hoffman | Unfinished Business Featured returning teams who lost their first race and wanted to prove they could win | ||

| 19 | June 18, 2011 | July 10, 2011 | September 25, 2011 | December 11, 2011 | Ernie Halvorsen & Cindy Chiang |

Introduced the Hazard and a double elimination | ||

| 20 | November 26, 2011 | December 19, 2011 | February 19, 2012 | May 6, 2012 | Rachel & Dave Brown, Jr. | |||

| 21 | May 26, 2012 | June 16, 2012 | September 30, 2012 | December 9, 2012 | Josh Kilmer-Purcell & Brent Ridge |

Introduced the Double Your Money prize[9] and the Blind Double U-Turn | ||

| 22 | November 13, 2012 | December 7, 2012 | February 17, 2013 | May 5, 2013 | Bates & Anthony Battaglia | Introduced a second Express Pass that must be given to another team | ||

| 23 | June 9, 2013 | July 2, 2013 | September 29, 2013 | December 8, 2013 | Jason Case & Amy Diaz |

|||

| 24 | November 16, 2013 | December 6, 2013 | February 23, 2014 | May 18, 2014 | Dave & Connor O' Leary | All-Stars Featured returning favorite teams, and a composite team | ||

| 25 | May 31, 2014 | June 22, 2014 | September 26, 2014 | December 19, 2014 | Amy DeJong & Maya Warren |

Introduced the Save and Blind Detour; first season to feature four teams racing in the final leg | ||

| 26 | November 12, 2014 | December 6, 2014[10] | February 25, 2015 | May 15, 2015 | Laura Pierson & Tyler Adams |

Featured dating teams, including five "blind date" teams meeting in person for the first time | ||

| 27 | June 22, 2015[11] | July 14, 2015 | September 25, 2015 | December 11, 2015 | Kelsey Gerckens & Joey Buttitta |

Introduced a single Express Pass that must be given to another team once used, and the recipients must use it in the following leg | ||

| 28 | November 15, 2015 | December 6, 2015 | February 12, 2016 | May 13, 2016 | Dana Alexa & Matt Steffanina |

Featured notable social media personalities[12] | ||

| 29 | June 10, 2016[13][14] | July 2, 2016[15] | March 30, 2017 | June 1, 2017[16] | Brooke Camhi & Scott Flanary |

Featured individual contestants that met and teamed up for the first time at the starting line[17] | ||

| 30 | October 1, 2017[18] | October 24, 2017[19] | January 3, 2018[1] | February 21, 2018 | Cody Nickson & Jessica Graf |

Introduced the Head-to-Head and the Partner Swap | ||

| 31 | June 10, 2018[20] | July 3, 2018[21] | To feature past contestants from Big Brother, Survivor and The Amazing Race[20][22] |

Production

Concept

The original idea for The Amazing Race came from Elise Doganieri and Bertram Van Munster. The two had previously met when Van Munster was producing programs such as Cops, and they continued to work together and eventually married. Around 2000, Van Munster was wrapping up production of his nature documentary series Wild Things, and he was looking for another concept. Doganieri, an advertising executive at that point, had come back from that year's MIPCOM, and she complained about the lack of good ideas from people working in television. Van Munster jokingly bet her on the spot to come up with an idea herself.[23] Though her by-then husband was only joking, Dogenieri declared him "on," and she recalled her previous experience backpacking across Europe and meeting and interacting with the various local residents, on which basis she offered the idea of several teams of players racing across the world, interspersed with local challenges that would test the team's resolve and relationships, and which teams would be eliminated along the way but not due to someone else doing something against that team.[24][25] Van Munster was intrigued with the idea, and had already had experience with "reality" television with Cops, considered to be the predecessor of reality television during the 1990s.[26] The two approached Jerry Bruckheimer and Jonathan Littman with the idea, and the four refined it into the concept of The Amazing Race. Van Munster pitched the idea to Les Moonves of CBS shortly thereafter, who greenlit the show by June 2000.[24][25] Initial scouting for locations for the first season started in August 2000, and filming took place between March and April 2001.[24]

Planning

Prior to each of the Races, the production team plans out the locations and tasks that the racers will travel, working in conjunction with local representatives, each of whom Van Munster had initially had available for a different show.[6] The staff also consults with ex-military or federal agents that are aware of political matters in foreign areas, who may advise on countries or regions to avoid.[27] Van Munster and others will then travel the proposed course to verify the locations and identify needs for filming for the show.[6] The crew works with local government representatives to assure the safety of the racers while traveling through certain areas of the world.[26] Despite pre-planning, the production crew may be faced with obstacles forcing them to change tasks or even locations. In one situation during planning of the second race, the Argentine bank system failed, creating political unrest, and a new country was selected.[6][27] Similarly, after the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 and the sexual assault of American reporter Lara Logan, the production staff considers Egypt to be "off the map right now."[27] It has been estimated, by Van Munster, that over 2,000 people worldwide are involved in the production of any one season of the Race.[6]

Tasks are generally selected to represent the local flavor of the country or region they are in. They typically look for activities that are not often considered something a tourist would do but part of the way of life in a country, as this would generally be a new experience for all the racers.[24] Production relies on their own experiences as well to develop tasks; Van Munster noted that a task in season 21 involving synchronized swimming was based on his own struggles as a teenager to learn how to do a similar routine, thus assuring that if he could do it, racers could do it as well.[24]

A Race's route has to be approved by CBS before production can start on their scouting.[24] The specific tasks, clues, and other Race elements like the sequence of non-elimination legs, are all set about a month before filming.[24] The production can allow for some flexibility to minimize the difficulties of production. In the first season, one pit stop was located and extended to 72 hours instead of the normal 12 due to a sandstorm. Also in that season, two of the four final teams ended up about 24 hours behind the lead teams due to flight and hours-of-operation limitations, creating a production nightmare. In later seasons, production has improvised extended pit stops by a day or so to prevent teams from becoming too spread out.[28] In the tenth season, Phil Keoghan, host of the Races, was detained by officials in Ukraine, where the ninth leg took place, and the local American ambassador, who happened to be a fan of the show, helped to free him.[29]

The producers review previous seasons and make changes to new seasons as to keep the show fresh and unexpected; Littman stated that with as many season now filmed of the Race, many racers come to know what to expect and as producers, they need a way to shake things up, as "whenever you throw a wrench into [the Race], it completely throws them off."[25] For example, while teams at Pit Stops during the first several seasons were allowed to mingle, the producers have since purposely kept teams apart during this time, as it serves to both keep teams unaware of the finishing order and the fate of an eliminated team, and prevents alliances from forming to keep the teams competitive.[25] They also looked to change the format of the team structure, but found that their first such experiment with the season 8 "Family Edition" was poorly received by American audiences though had a strong reception from overseas broadcasts of that series.[25]

Though The Amazing Race involves significant amounts of travel across the world for around a hundred people, Doganieri has published her own estimates that their production costs are in line with, if not less than, those of other reality television shows, which estimates she bases in part on the fact that most of the production staff have been with the show for a long period and work efficiently to help move the competition.[30] The cost of the show has been subsidized by its sponsors, who provide trips and other prizes to teams that arrive first on certain legs, or have their products featured as a task. For example, more recent seasons have been sponsored by Travelocity, and typically one leg per season will involve a task that includes the Travelocity "Roaming Gnome;" trip prizes for first-place finishes on many legs are funded by Travelocity and the local hotel at the trip destination.[28][31] Ford Motor Company is also a major sponsor in later seasons of the show, and typically teams will be given Ford vehicles to drive for various legs and as prizes for finishing first on a leg.[28] In another example, a tea-themed leg in the 18th season was sponsored by Snapple Beverages, which had developed a new limited edition flavor specifically for the show.[32] The Amazing Race has been considered to be a show that incorporates a large number of product placements as tracked by ACNeilsen, often being one of the top shows for product placement each year.[33]

Casting

The Amazing Race has been hosted by New Zealander Phil Keoghan since its 2001 debut. Keoghan initiates the start of the race, introduces each new area and describes each task for the viewers, and meets each team at the Pit Stops along with a local greeter informing the teams of their placement or their elimination followed by a short interview, as well as announcing the winners at the finish line. Keoghan was a television host in New Zealand prior to The Amazing Race, and had traveled the world and performed adventurous feats for these shows.[34] His background led him to apply for the hosting duties of Survivor. Though Keoghan was on the shortlist, the producers of Survivor chose Jeff Probst, while Keoghan was found to be a better fit for The Amazing Race.[35] Keoghan's performance as a host has been highlighted by his ability to arch his eyebrows to the arriving teams to increase suspense before revealing their position,[8][36] and racers and fans of the show often refer to the progressive elimination of teams as "Philimination".[37] Keoghan signed an extended contract with CBS to continue hosting The Amazing Race for "several years", according to TV Guide, shortly after the conclusion of The Amazing Race 18. The contract will also allow Keoghan to develop ideas into shows for the network.[38]

Prior to each race, CBS and World Race Productions hold casting auditions around the country and accept submissions through postal mail. More recent seasons have included recruited contestants.[28] According to casting director Lynne Spillman, they look to cast a diverse array of teams to appeal to a wide range of audience members. Spillman notes they put more value on contestants that are "great talkers" as well as racers, and see those that have deep knowledge of the Race as a plus over other factors like looks and strength.[25] The casting process takes about four months to complete.[30] All teams are compensated for the time missed from their jobs, though the amount is undisclosed and confidential; one racer claimed that most people would lose money from the Race stipend compared to their typical salaries.[28][39] While the producers prefer to use teams that have never been on the show before or celebrities, they are at times pressured by CBS to include known people.[40]

Each member of the two-person teams is required to be adult American citizen with an existing relationship with their teammate; according to Keoghan, in contrast to other reality television shows that pit individuals against each other, "it's more interesting to see how an experience like [the Race] affects an existing relationship".[23] Teams are primarily married and dating couples (regardless of sexual orientation), near and distant relatives, co-workers, and friends. Most teams that participate are average Americans, but The Amazing Race has included teams or team members with some celebrity status. This has included contestants from other reality TV shows, including Alison Irwin, Jordan Lloyd, Jeff Schroeder, Rachel Reilly, Brendon Villegas, Cody Nickson and Jessica Graf from Big Brother; Rob Mariano, Amber Mariano (née Brkich), Ethan Zohn, Jenna Morasca, Keith Tollefson, and Whitney Duncan from Survivor; and The Fabulous Beekman Boys stars Josh Kilmer-Purcell and Brent Ridge. Several professional athletes have also participated, including the Harlem Globetrotters Herbert "Flight Time" Lang and Nathaniel "Big Easy" Lofton; former NFL players Ken Greene, Marcus Pollard, Chester Pitts, and Ephraim Salaam; professional bull and bronco rider Cord McCoy; professional snowboarders Andy Finch and Amy Purdy; Ironman Triathlon competitor Sarah Reinertsen; Major League Soccer goalkeeper Andrew Weber; professional hockey players Bates Battaglia and Anthony Battaglia; professional surfer and survivor of a shark attack Bethany Hamilton, former NBA All-Star Shawn Marion and Cedric Ceballos, IndyCar racers Alexander Rossi and Conor Daly, and professional skiers & X-Games champions Kristi Leskinen and Jen Hudak. Numerous beauty pageant participants and winners have raced on the show, including Nicole O'Brian, Christie Lee Woods, Dustin-Leigh Konzelman, Kandice Pelletier, Ericka Dunlap, Caitlin Upton, Mallory Ervin, Stephanie Murray Smith, Brook Roberts, and Amy Diaz. Other celebrities include father and son screenwriters and actors Mike and Mel White, professional poker players Maria Ho and Tiffany Michelle, former prisoner of war from the Iraq war Ron Young, professional sailor Zac Sunderland, YouTube stars Kevin "KevJumba" Wu and Joey Graceffa. The show's 28th season was primarily made up of social media celebrities and their partners, friends, or relatives as a means to capture a younger audience demographic. The show's 29th season featured 22 strangers who met for the first time at the starting line. Three special seasons of the Race have featured returning teams or racers.

Racers have found fame in part due to their appearance on The Amazing Race. Chip Arndt, who had raced with his civil partner Reichen Lehmkuhl, has become an activist for lesbian and gay community. Blake Mycoskie, based on his experiences traveling to Argentina during the race, later founded TOMS Shoes with the concept to donate one pair of shoes to poor children in countries like Argentina for each one sold.[41] Dating goth couple Kent "Kynt" Kaliber and Vyxsin Fiala have become models for the Hot Topic chain of punk/rock culture clothing stores after their appearance on the show.[42] Cord McCoy and his brother and Race partner Jet are using their experience from both their cattle ranching and from the Race as well as their celebrity status from their appearance to run for separate positions in the 2017 Oklahoma legislature.[43]

Filming

Through the 17th season of the Race, the show used standard-definition television cameras despite the move of most other primetime shows, including reality television shows like Survivor, to high-definition television (HD) cameras prior to 2010. Worldrace Productions cited the cost and fragility of HD equipment as a barrier to its use for the Race.[44] While other scripted or reality shows that film in one location have the ability to replace equipment quickly from a nearby facility, the mobile nature of the Race made the prospect of using HD difficult.[45] The 18th season of the Race, filmed in late 2010, was the first to be filmed in HD.[44] The production team uses Sony XDCAMs, allowing the filming to be transferred directly to digital format and couriered to the editors.[45]

Prior to the filming of the race, selected teams are given a list of countries - including additional countries that are not planned for the race - for which they will need to apply for visas.[46] Teams prepare backpacks for clothing, hygiene, and other personal items; the racers are given a list of items that are forbidden from taking. Electronics like laptops, cell phones, and GPS devices are banned from the race, and racers are asked to avoid clothing with brand logos.[47][28][48] Travelers can not bring maps ahead of time, although they can buy maps during the competition if they choose.[47] A few days before the race, teams are sequestered at a hotel for a final review of the rules, before they are finally taken to the race starting line.[28][49] Several takes of the start of the Race are recorded for production of the show and to go over any final rules clarifications with the racers, before the Race is officially started.[50]

Once the Race starts, each team is accompanied by a two-person audio/video crew that films and records the team, alongside body mics worn by the racers.[51] Unless otherwise indicated, the crew must be able to accompany the team through all travels; for example, teams must be able to acquire four tickets on a single flight or otherwise cannot take that flight. Four tickets are usually purchased off-camera using a credit card supplied by World Race Productions.[52] The crews rotate between teams at Pit Stops to avoid any possible favoritism that may develop between a team and its crew, and to avoid giving the appearance of collusion.[25][53] At pit stops, a team of captains that accurately record arrival times, amounts of money teams have remaining, and other factors to make sure that racers have properly completed each leg, assuring that the Race is run in a fair manner.[24] The production team will remind players about critical local rules and laws they must follow to avoid any legal conflicts, but otherwise try to avoid giving too many instructions to players; Littman stated they chose not to interfere too much as "that’s when you get the best material. They’re wild cards."[25] van Munster stated: "...when Phil yells 'Go,' it’s 'Action' until three weeks later when we say 'Cut.'"[24]

The production crew, including Keoghan, Doganieri, and van Munster, all typically travel to the next destination of the race ahead of the teams. In planning the race, the production team develops what Doganieri calls a Fast/Slow document, outlining what they believe is the fastest and slowest times that a team may take to complete all tasks on a leg based on test runs, from which they use to plan their travel ahead of the teams. According to Doganieri, this Fast/Slow document has been about 98% accurate through all seasons through 2014.[24] Productions work with local agents, representatives, and film crews to prepare for the tasks before the racers arrive, and are in coordination with the audio/video crews to track racers during a leg.[54] For example, to prevent clue boxes from being interfered with by locals, they are covered with garbage bags and monitored by production staff, and only when teams are about five minutes out are the bags removed.[24] At times, the production team has been only minutes ahead of teams before they check into the Pit Stop, forcing production to restage the teams' arrival there once they are ready.[6][54] Since the 25th season, Keoghan has been featured filming explanations for tasks as racers ran about behind him.

Most eliminated teams are sent to a resort destination informally dubbed "Sequesterville", where they will wait until the end of the race to be flown into the final destination city so they can be present at the Finish Line.[28][55] In later seasons, short web videos hosted by CBS titled "Elimination Station" show the events at this location as new teams arrive and the events that occur during the teams' stay. Other teams, generally the last few eliminated before the final three, are used as "decoy teams", and run the race's final leg ahead of the actual final teams, in hopes of confusing possible spoilers about the race's outcome from locals.[56] Keoghan has also recorded his own videos during the show's filming, used to show what happens behind the scenes to viewers.[8]

Countries and locales visited

Most race routes in The Amazing Race circumnavigate the globe, starting from one United States city and ending in another. Exceptions include:

- In three seasons, the race began and ended in the same city: season one (New York City), season six (Chicago), and season nine (Denver); only in season nine was the starting line and finish line in the same place (Red Rocks Amphitheater)

- Season seven crossed through Argentina, South Africa, and India before returning westward to Europe

- Season eight (also known as Family Edition), which stayed entirely within North America

- Season twenty-eight began in the contestants' homes – scattered across the United States – via video chat with Phil Keoghan. Teams were instructed to travel to that season's first destination city, Mexico City.

Country counts

As of season 30, The Amazing Race has visited 89 different countries.[lower-alpha 1] Other than the United States, the most visited country in the original American series is China, with 21 Pit Stops in 10 different cities among 14 seasons.

North America

South America

Europe

|

Africa

Asia

Oceania

|

Continent counts

The first season of The Amazing Race visited four continents in total (three if excluding the United States). Season two extended the Race route to South America and Oceania, and season three was the first time having route markers in North America outside the United States. The Race has yet to visit Antarctica.

| Rank | Continent | Seasons visited |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | North America (50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C. included) | All |

| 2 | Asia | 29 (1–7, 9–30) |

| 3 | Europe | 28 (1, 3–7, 9–30) |

| 4 | Africa | 19 (1–3, 5–7, 10–12, 16, 17, 19, 20, 22, 25–27, 29, 30) |

| 5 | South America | 14 (2, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 16, 18, 20, 23, 26–29) |

| 6 | Oceania | 8 (2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 13, 18, 22) |

| North America (50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C. excluded) | 8 (3, 5, 7, 8, 19, 25, 28, 29) |

Notes

- ↑ This count only includes countries that fielded actual route markers, challenges or finish mats. Airport stopovers and mandatory layovers are not counted or listed.[57]

- ↑ Including the unincorporated organized territories of the Commonwealth of

- ↑ Includes 30 Finish Lines

- ↑ Including the overseas country of

- ↑ Includes the region of Siberia (14), which is part of the Asian continent.

- ↑ As of season 25, the show has visited all four of the constituent countries of the United Kingdom:

.svg.png)

- ↑ An aired Detour option in season 1 required teams to travel to Botswana, but no one chose the option.

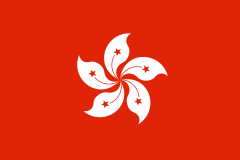

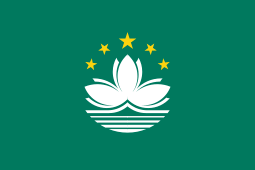

- ↑ Including the Special Administrative Regions of

Impact and reception

U.S. broadcast and ratings

Seasonal rankings (based on average total viewers per episode) of The Amazing Race on CBS.

| Season | Timeslot (ET) | Season premiere | Premiere viewers (millions) |

Season finale | Finale viewers (millions) |

TV season[lower-roman 1] | Rank | Average viewers (millions) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wednesday 9:00 pm | September 5, 2001 | 11.80[58] | December 13, 2001 | 13.65[59] | 2001–02 | 73[60] | 8.80[60] |

| 2 | March 11, 2002 | 12.50[61] | May 15, 2002 | 11.30[61] | 49[60] | 10.30[60] | ||

| 3 | October 2, 2002 | 9.50[61] | December 18, 2002 | 11.00[61] | 2002 | 71[62] | 8.98[62] | |

| 4 | Thursday 8:00 pm | May 29, 2003 | 9.94[63] | August 21, 2003 | 9.90[61] | 2003 | N/A[lower-roman 2] | 8.32[64] |

| 5 | Tuesday 10:00 pm | July 6, 2004 | 10.30[65] | September 21, 2004 | 12.90[66] | 2004 | N/A[lower-roman 2] | 10.73[67] |

| 6 | Tuesday 9:00 pm | November 16, 2004 | 11.80[68] | February 8, 2005 | 12.60[66] | 2004–05 | 31[69] | 11.54[69] |

| 7 | March 1, 2005 | 11.80[66] | May 10, 2005 | 16.01[70] | 25[69] | 13.05[69] | ||

| 8 | September 27, 2005 | 10.60[66] | December 13, 2005 | 11.50[66] | 2005–06 | 42[71] | 10.80[71] | |

| 9 | Tuesday 9:00 pm[lower-roman 3] Tuesday 10:00 pm[lower-roman 4] Wednesday 8:00 pm[lower-roman 4] |

February 28, 2006 | 10.40[66] | May 17, 2006 | 9.00[72] | 56[71] | 9.10[71] | |

| 10 | Sunday 8:00 pm | September 17, 2006 | 10.10[72] | December 10, 2006 | 12.70[72] | 2006–07 | 31[73] | 11.50[73] |

| 11 | February 18, 2007 | 10.30[72] | May 6, 2007 | 10.30[72] | 44[73] | 10.10[73] | ||

| 12 | November 4, 2007 | 13.70[72] | January 20, 2008 | 9.75[74] | 2007–08 | 25[75] | 11.84[75] | |

| 13 | September 28, 2008 | 10.29[76] | December 7, 2008 | 10.57[77] | 2008–09 | 27[78] | 11.14[78] | |

| 14 | February 15, 2009 | 9.20[79] | May 10, 2009 | 10.49[80] | 29[78] | 10.91[78] | ||

| 15 | September 27, 2009 | 10.40[81] | December 6, 2009 | 12.32[82] | 2009–10 | 28[83] | 11.14[83] | |

| 16 | February 14, 2010 | 8.90[84] | May 9, 2010 | 10.63[85] | 29[83] | 10.40[83] | ||

| 17 | September 26, 2010 | 11.54[86] | December 12, 2010 | 12.12[87] | 2010–11 | 22[88] | 11.93[88] | |

| 18 | February 20, 2011 | 9.15[89] | May 8, 2011 | 8.97[90] | 39[88] | 10.35[88] | ||

| 19 | September 25, 2011 | 10.18[91] | December 11, 2011 | 11.72[92] | 2011–12 | 34[93] | 11.13[93] | |

| 20 | February 19, 2012 | 10.34[94] | May 6, 2012 | 9.40[95] | 37[93] | 10.30[93] | ||

| 21 | September 30, 2012 | 9.40[96] | December 9, 2012 | 9.35[97] | 2012–13 | 29[98] | 10.68[98] | |

| 22 | February 17, 2013 | 9.57[99] | May 5, 2013 | 9.10[100] | 36[98] | 10.17[98] | ||

| 23 | September 29, 2013 | 8.62[101] | December 8, 2013 | 9.21[102] | 2013–14[lower-roman 5] | 34[103] | 9.49[103] | |

| 24 | February 23, 2014 | 6.71[104] | May 18, 2014 | 8.22[105] | ||||

| 25 | Friday 8:00 pm | September 26, 2014 | 5.48[106] | December 19, 2014 | 6.59[107] | 2014–15[lower-roman 6] | 69[108] | 7.49[108] |

| 26 | Wednesday 9:30 pm[lower-roman 7] Friday 8:00 pm |

February 25, 2015 | 6.16[109] | May 15, 2015 | 5.72[110] | |||

| 27 | Friday 8:00 pm | September 25, 2015 | 5.79[111] | December 11, 2015 | 6.16[112] | 2015–16 | 58[113] | 7.56[113] |

| 28 | February 12, 2016 | 6.09[114] | May 13, 2016 | 5.93[115] | ||||

| 29 | Thursday 10:00 pm[lower-roman 8] | March 30, 2017 | 4.30[116] | June 1, 2017[16] | 3.91[117] | 2016–17 | 64[118] | 6.33[118] |

| 30 | Wednesday 8:00 pm[lower-roman 9] Wednesday 9:00 pm[lower-roman 9] |

January 3, 2018[1] | 7.33[119] | February 21, 2018 | 4.34[120] | 2017–18 | 50[121] | 7.70[121] |

- Notes

- ↑ Each U.S. network television season starts in late September and ends in late May, which coincides with the completion of May sweeps.

- 1 2 Because this edition of The Amazing Race aired during the summer (and outside of the typical television season, which runs September to May), it was not ranked in either the television season preceding it or succeeding it.

- ↑ The two-hour premiere was the only episode to air Tuesday at 9:00 pm.

- 1 2 Episodes aired Tuesdays at 10:00 pm during the entire month of March 2006, and then moved to Wednesdays at 8:00 pm for the remainder of the season to make room for CSI: NY.

- ↑ Starting from 2013–14 TV season ranking, the two seasons are listed together in the final rankings together as The Amazing Race. Previously, seasons were listed separately.

- ↑ Starting with the 2014-15 season, final season viewer averages are based on Live+7 ratings data.

- ↑ The ninety-minute premiere was the only episode to air Wednesday at 9:30 pm.

- ↑ Two episodes aired on April 20 and May 18, with the first airing at the earlier time of 9:00 pm and the second at the regular time.

- 1 2 Episodes aired Wednesdays at 8:00 pm during the entire month of January 2018, and then moved to Wednesdays at 9:00 pm for the remainder of the season to make way for Celebrity Big Brother, all in 2-hour episodes.

During its first four seasons, even with extensive critical praise, the show garnered low Nielsen ratings, facing cancellation a number of times. The premiere of the show aired six days before the September 11 attacks, leaving the fate of the show in doubt. Producer van Munster stated that "Once we saw our billboards covered in dust from the 9/11 tragedy, we knew we had a problem".[56] Low viewership of the show was also attributed to it being lost among all other reality television shows at the time and unable to garner similar numbers as Survivor.[56] The Amazing Race premiered against a similarly themed reality show, Lost on NBC (unrelated to the ABC series of the same name); Lost featured teams of two stranded in a remote area of the world and forced to find their way back to the United States.[122] A vice president of programming at CBS considered The Amazing Race to be "a show that was always on the bubble" of being canceled.[56]

The show was considered to be saved due to several factors: the show was well received by critics, winning the Emmy for Outstanding Reality-Competition Programming in 2003 and 2004; consistent viewership numbers; and feedback from the large number of fans representing the young target demographic, including Sarah Jessica Parker, who had called in directly to CBS President Les Moonves asking to save the show.[56][123][124] The fifth season of the series, which aired from July to September 2004, had very high viewership numbers for that time of the year, averaging 10.7 million with a finale of nearly 13 million, doubling the viewership in the 18-to-34 demographic and won its time slot for every episode.[56] The improved ratings are credited to the particular teams selected for that season.[123] As a result, CBS began airing the sixth season during the "high-profile heart" of the November 2004 sweeps.[56] The New York Times's Kate Aurthur suggests that ratings increases for the fifth, sixth, and seven season were a direct result of the show having racers that were portrayed as "villain" characters (specifically, Colin from season 5, Jonathan from season 6, and Rob and Amber from season 7) that created more tension between teams than previous seasons, and gave viewers teams to root for or against.[125]

A temporary setback struck The Amazing Race after a Family Edition that aired in the fall of 2005 was not received warmly by viewers, which resulted in lowered viewership.[126] The change in format, with teams of four and allowing for young children to race alongside their parents, hampered the travel ability of the show.[127] Keoghan, though pleased they had tried something different with the show, attributed the poor response to the Family Edition due to too many people to follow and lack of exotic locations.[128] This spilled over to Season 9 where it experienced dismaying ratings of only an average of 9.1 million viewers per episode, a drop from 13 million just 2 seasons ago in Season 7. The timeslot changing for Season 9 was also attributed to the drop in ratings.

From the tenth season to the twenty-fourth season, the show was moved to Sunday nights; as a result, The Amazing Race has seen further increases in its numbers. It is believed that part of this increase is due to "sports overruns" (football, basketball, or golf) that resulted from games played earlier on Sunday pushing the airtime for The Amazing Race back by some amount on the East Coast along with other CBS programming.[129][130] In the Sunday timeslot, The Amazing Race follows 60 Minutes; Variety states that, while both shows have different target demographics, the crossover audience between the shows is very high based on the average household income of its viewers, and is part of the Race's success.[131] In the 2010 season, another reality television show, Undercover Boss, was scheduled following The Amazing Race; the overall impact of these three shows have helped CBS to regain viewership on Sunday nights.[132] According to Variety, the average age of Amazing Race viewers that watch the show live in 2009 was 51.9 years, while for those that time-shifted the show, the average age was 39.2 years.[133] In a 2010 survey by Experian Simmons, The Amazing Race was found to be the second-highest show proportion of viewers that identify themselves as Republicans, following Glenn Beck.[134] The season 16 finale, however, was the lowest-rated finale since season 4.[135]

Although season 18 averaged over 10 million viewers and finished in top 40 most watched shows of the 2010-2011 television season, the ratings dropped and the season 18 finale was the second-lowest-rated Sunday night finale.[136] The season 21 finale was down 31% from the season 19 finale on December 11, 2011. It tied as the show's lowest rated finale ever.[97][137][138] Ratings also dropped during the season 24 finale, which was down 33% from the season 15 finale on May 18, 2014. As a result of decreasing ratings, starting with the twenty-fifth season, the show moved to Fridays at 8:00 pm, where it had its lowest viewership ever in this series.[139] Ratings for the show since the move to Friday have remained steady, with seasons premieres maintaining around 6 million viewers and only small drops over the course of a given season.[140] With the show's age, some of its current fans were not born when the show had first aired in 2001, and the production team used a concept like season 28, aired in 2016, where the use of YouTube and other Internet celebrities was intended to help bridge the gap between long-time and new fans.[140]

The 30th season of the show was moved by CBS to a Wednesday night slot, and resulted in an improvement in viewership from previous seasons. van Munster and Doganieri credit this new timeslot to help boost ratings, as it is more amenable for family viewing than previous timeslots.[40]

The success of The Amazing Race has led other networks to attempt to develop reality shows in a similar vein; CBS Vice President for alternative programming Jennifer Bresnan stated that many of these shows pose themselves as "The Amazing Race mixed with 'X'" to try to vary the format.[141] Such shows include Treasure Hunters (NBC, 2006), Expedition Impossible (ABC, 2011), and Around the World in 80 Plates (Bravo, 2012).[141] The Great Escape (TNT, 2012) brought van Munster and Doganieri to help with production, and was considered by critics as a "lite" version of The Amazing Race.[142]

International broadcast and versions

The United States version of The Amazing Race is rebroadcast in several countries around the world. Airings in both Canada and Australia are very popular. The Canadian showing on CTV is commonly one of the top ten most watched shows each week, according to BBM Canada,[143] Australian broadcasts of the episodes on the Seven Network often fall into the top 20 programs for the week.[144][145] Episodes of The Amazing Race also air in several other countries shortly after the American broadcast, including Israel, Latin America, China, Vietnam and the Philippines.

AXN Asia broadcasts The Amazing Race across southeast Asia; the popularity of the show through the service led to CBS allowing for the option of creating international versions of the show in October 2005. The Amazing Race Asia was one of the first versions created, following essentially the same format as the United States version.

Other international versions of the show have been produced out of Latin America, Europe, Israel, Australia, and Canada.

Critical reception

Part of the show's success is considered to be the relatively simple formula of following several teams on a race around the world. Because of this, viewers can live "vicariously through the people on the screen", according to Andy Dehnart of the RealityBlurred.com website.[56] The show is often considered to be "travel porn", offering locations that most people would never get to see in their lifetimes.[146][147] Keoghan offers that:

"[The Amazing Race] exposes particular Americans to a world they don't see in primetime TV. Most of what they see is a war here, a person killed there, a natural disaster over here. We present a world that seems inviting, with people who are warm and helpful, not this big scary place that if you get in a plane you're going to be killed by traveling to some foreign land.", Phil Keoghan[35]

The show is also considered to be successful in that it does not rely on the typical tropes of reality television, where players are trying to avoid becoming too much of a target to be voted off by their fellow contestants; in The Amazing Race, a team's success is primarily based on their own performance.[148] At the same time, the reality show setting can bring out unbecoming behavior, often leading to the stereotypical idea of ugly American tourists.[146]

Latter seasons of the Race have been more critically panned. One factor is the predictability of the show, with little variety in the construction of specific legs and foregone outcomes of which team would be eliminated. The media site The A.V. Club, which had covered the Race for several seasons, opted to end its Race recaps mid-Season 21, with editor Scott Von Doviak stating that the show "has become so stale and predictable".[149] Though Denhert was a supporter of the show in its earlier seasons, he has criticized latter seasons for becoming too predictable, as "failed to grow and evolve, it seems stale".[150] Denhert does acknowledge that budget cuts for all CBS programming, including the Race, are likely causes for simple tasks and lackluster legs;[150] Keoghan does state that the reduced budgets has made the timetable for filming "really brutal", but also considers that the difficulty of filming also reflects on the difficulty of the Race for the teams as well.[151] Denhert further points to the lack of time given for the viewer to learn about the individuals on each team, and instead has added elements like the U-Turn and the Yield to create inter-team drama.[150]

The show is known for a dedicated fan base that keeps in touch with the show's producers and contestants.[152] While a race is being run and filmed, fans of the show watch for news or spotting of the racers and attempt to track their progress in real time, enhanced by recent social media tools, leading production to figure out ways to masquerade their presence in any city such as through the use of decoy teams.[35][56][153] Despite this, fans readily track the Race as it is being run across the globe. In the 19th season, one contestant had lost her passport at a gas station while getting directions to Los Angeles International Airport. Though spotted by their A/V crew, they could not intervene, but instead alerted production, who prepared for an early elimination of the team at LAX. A bystander found the passport, and after he posted about it on Twitter, he was directed by a fan tracking the Race's progress to take the passport to the airport, returning it before the scheduled flight and keeping the team in the race.[154] Subsequent seasons have had publicly attended live starts such as starting in Times Square for season 25, and frequent use of live social media updates by the racers by permission of production during season 28.

Coinciding with the broadcast finale for each season though about the 13th season, fans from the website Television Without Pity arranged for a "TARCon" event in New York City along with the season's teams and other former racers.[54]

Awards and nominations

The Amazing Race won the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Reality-Competition Program for the first seven years after the creation of the award in 2003, and ten of the twelve years since its creation, against other, more popular reality TV shows such as Survivor, Dancing with the Stars, and American Idol. Its streak was ended in 2010 when Top Chef won the Emmy for this category.[155] Host Phil Keoghan revealed in an interview that the show's loss that year made him and the producers realize that they will have to try harder to win the Emmy again.[156] In 2011, the show won in the category again for the eighth time.[157] After its seventh consecutive win, some in the media, including Survivor host Jeff Probst suggested that The Amazing Race willingly drop out from the competition in future years, similar to Candice Bergen declining any further nominations after her fifth Emmy win for her role in Murphy Brown. Van Munster has stated that it is "not likely" he will pull the show from future Emmy awards, considering that it reflects on his and his crew's hard work and high standards.[158] The show has also been nominated and won several times for technical production (Creative Arts) Emmy awards, for Cinematography and Picture Editing for Non-Fiction programs, whereas it has only been nominated for Sound Mixing and Sound Editing for Non-Fiction programs. The show has been nominated in the same five categories for three years consecutively, a trend which continued with the 2007 Primetime Emmy Awards.

| Year | Type | Category | Result | Record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 1 for 1 |

| 2004 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 2 for 2 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Could Never Have Been Prepared For What I'm Looking At Right Now" |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | |

| Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Could Never Have Been Prepared For What I'm Looking At Right Now" |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Could Never Have Been Prepared For What I'm Looking At Right Now" |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | ||

| 2005 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 3 for 3 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "We're Moving Up the Food Chain" |

Won | 1 for 2 | |

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "We're Moving Up the Food Chain" |

Nominated | 0 for 2 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "We're Moving Up the Food Chain" |

Nominated | 0 for 2 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "We're Moving Up the Food Chain" |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | ||

| 2006 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 4 for 4 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Here Comes The Bedouin!" |

Won | 2 for 3 | |

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Here Comes The Bedouin!" |

Won | 1 for 3 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Here Comes The Bedouin!" |

Nominated | 0 for 3 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Here Comes The Bedouin!" |

Nominated | 0 for 2 | ||

| 2007 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 5 for 5 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Know Phil, Little Ol' Gorgeous Thing!" |

Won | 3 for 4 | |

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Know Phil, Little Ol' Gorgeous Thing!" |

Won | 2 for 4 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Know Phil, Little Ol' Gorgeous Thing!" |

Nominated | 0 for 4 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Know Phil, Little Ol' Gorgeous Thing!" |

Nominated | 0 for 3 | ||

| 2008 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 6 for 6 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Honestly, They Have Witch Powers Or Something" |

Nominated | 3 for 5 | |

| Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "Honestly, They Have Witch Powers Or Something" |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Honestly, They Have Witch Powers Or Something" |

Nominated | 2 for 5 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Honestly, They Have Witch Powers Or Something" |

Nominated | 0 for 5 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Honestly, They Have Witch Powers Or Something" |

Nominated | 0 for 4 | ||

| 2009 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 7 for 7 |

| Outstanding Host for a Reality or Reality-Competition Program Phil Keoghan |

Nominated | 0 for 1 | ||

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Don't Let A Cheese Hit Me" |

Nominated | 3 for 6 | |

| Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "Don't Let A Cheese Hit Me" |

Nominated | 0 for 2 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Don't Let A Cheese Hit Me" |

Nominated | 2 for 6 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Don't Let A Cheese Hit Me" |

Nominated | 0 for 6 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Don't Let A Cheese Hit Me" |

Nominated | 0 for 5 | ||

| 2010 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 7 for 8 |

| Outstanding Host for a Reality or Reality-Competition Program Phil Keoghan |

Nominated | 0 for 2 | ||

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Think We're Fighting the Germans. Right?" |

Nominated | 3 for 7 | |

| Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "I Think We're Fighting the Germans. Right?" |

Nominated | 0 for 3 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Think We're Fighting the Germans. Right?" |

Nominated | 2 for 7 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Think We're Fighting the Germans. Right?" |

Nominated | 0 for 7 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "I Think We're Fighting the Germans. Right?" |

Nominated | 0 for 6 | ||

| 2011 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 8 for 9 |

| Outstanding Host for a Reality or Reality-Competition Program Phil Keoghan |

Nominated | 0 for 3 | ||

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "You Don't Get Paid Unless You Win" |

Nominated | 3 for 8 | |

| Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "You Don't Get Paid Unless You Win" |

Nominated | 0 for 4 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "You Don't Get Paid Unless You Win" |

Nominated | 2 for 8 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "You Don't Get Paid Unless You Win" |

Nominated | 0 for 8 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "You Don't Get Paid Unless You Win" |

Nominated | 0 for 7 | ||

| 2012 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 9 for 10 |

| Outstanding Host for a Reality or Reality-Competition Program Phil Keoghan |

Nominated | 0 for 4 | ||

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "Let Them Drink Their Haterade" |

Nominated | 3 for 9 | |

| Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "Let Them Drink Their Haterade" |

Nominated | 0 for 5 | ||

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Let Them Drink Their Haterade" |

Nominated | 2 for 9 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Let Them Drink Their Haterade" |

Nominated | 0 for 9 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Let Them Drink Their Haterade" |

Nominated | 0 for 8 | ||

| 2013 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 9 for 11 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "Be Safe and Don't Hit a Cow" |

Nominated | 3 for 10 | |

| Outstanding Cinematography for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Be Safe and Don't Hit a Cow" |

Nominated | 2 for 10 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Be Safe and Don't Hit a Cow" |

Nominated | 0 for 10 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Be Safe and Don't Hit a Cow" |

Nominated | 0 for 9 | ||

| 2014 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Won | 10 for 12 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Directing for Nonfiction Programming for the episode "Part Like the Red Sea" |

Nominated | 0 for 6 | |

| Outstanding Cinematography for Reality Programming for the episode "Part Like the Red Sea" |

Nominated | 2 for 11 | ||

| Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "Part Like the Red Sea" |

Nominated | 3 for 11 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Mixing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Part Like the Red Sea" |

Nominated | 0 for 11 | ||

| Outstanding Sound Editing for Nonfiction Programming (Single or Multi-Camera) for the episode "Part Like the Red Sea" |

Nominated | 0 for 10 | ||

| 2015 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 10 for 13 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Cinematography for Reality Programming for the episode "Morocc'and Roll" |

Nominated | 2 for 12 | |

| Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "Morocc'and Roll" |

Nominated | 3 for 12 | ||

| 2016 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 10 for 14 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Cinematography for Reality Programming for the episode "We're Only Doing Freaky Stuff Today" |

Nominated | 2 for 13 | |

| Outstanding Picture Editing for Reality Programming for the episode "We're Only Doing Freaky Stuff Today" |

Nominated | 3 for 12 | ||

| 2017 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 10 for 15 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Cinematography for Reality Programming for the episode "Bucket List Type Stuff" |

Nominated | 2 for 14 | |

| Outstanding Picture Editing For A Structured Or Competition Reality Program for the episode "Bucket List Type Stuff" |

Nominated | 3 for 14 | ||

| 2018 | Primetime | Outstanding Reality-Competition Program | Nominated | 10 for 16 |

| Creative Arts | Outstanding Directing for a Reality Program Bertram van Munster, for the episode "It’s Just A Million Dollars, No Pressure" |

Nominated | 0 for 7 | |

| Outstanding Cinematography for Reality Programming for the episode "It’s Just A Million Dollars, No Pressure" |

Nominated | 2 for 15 | ||

| Outstanding Picture Editing For A Structured Or Competition Reality Program for the episode "It’s Just A Million Dollars, No Pressure" |

Nominated | 3 for 16 | ||

| Total: 15 wins, 74 nominations | ||||

The production staff of The Amazing Race has been nominated each year since 2004 for the Producers Guild of America's Golden Laurel award for Television Producer of a Non-Fiction Program, and won this award in 2005.

Bert Van Munster has been nominated six times for the Directors Guild of America Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Reality Programs award for The Amazing Race each year between 2005 and 2010, and winning the award in 2007.[159][160][161][162]

Due to its favorable portrayal of gay couples, The Amazing Race has been nominated in 2004 and 2006 for, but not won, the GLAAD Media Award Outstanding Reality Program.[163] It has received a similar nomination for 2009,[164] and won in 2012.[165]

Home media releases

Seasons 1 and 7 were released in stores. while other seasons have been released exclusively on Amazon.com through its CreateSpace manufacture on demand program. Only region 1 is available. Select seasons have also been released on Blu-ray.

Other media

Two board games have been made based on The Amazing Race: a DVD Board Game[167] and a traditional board game. A video game for the Wii home game console has been also been produced as well as an iOS version.[168]

Two books have been written by fans of the show; the first is written by Adam-Troy Castro, titled "My Ox Is Broken!": Detours, Roadblocks, Fast Forwards and Other Great Moments from TV's The Amazing Race", which features an introduction from Season 8 racers Billy and Carissa Gaghan.[169] The second book is "Circumnavigating the Globe: Amazing Race 10 to 14 and Amazing Race Asia 1 to 3" written by Arthur E. Perkins Jr.[170]

Legacy

- The format of The Amazing Race has led to much smaller scale events for local cities and towns, having teams race through the area with clues and tasks.

- Countries and cities that are featured on the show often see the exposure as a boon. A member of the Icelandic Tourist Board noted that after their country shown as one of the locations in The Amazing Race 6, their website saw an increase in information requests, and they worked to develop a "Trace the Race" travel package to allow visitors to see the same locations shown on the show.[171]

- "Competitours" was created by Steve Belkin to create 8 to 14-days European tours in the style of The Amazing Race; the tourists are only given instructions each night on where they will be traveling next with a Race-like task to do the next day (such as encouraging locals to dance with them at a tourist location), to be demonstrated by recording themselves with a video camera.[172]

- The Amazing Race has inspired popular culture, with notable references to it in such shows as Robot Chicken,[173] MadTV (in which Charla and Mirna of Season 5 participated),[174] 30 Rock[175], American Dad (which US host, Phil Keoghan guest starred in the episode)[176], The Simpsons (in the episode "Heartbreak Hotel", where Marge Simpsons is shown to be a super-fan of a travel competition show The Amazing Place),[177] even Sesame Street.[178][179] The Canadian cartoon/reality show Total Drama Presents: The Ridonculous Race is a direct parody of The Amazing Race. Additionally, an episode titled "The Amazing Model Race" of the twelfth cycle of America's Next Top Model, featured a race-themed challenge.[180]

References

- 1 2 3 Romero, Nick (December 1, 2017). "Celebrity Big Brother to air opposite the Winter Olympics". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ↑ Littleton, Cynthia (May 13, 2017). "CBS Renews 'Elementary' and 'The Amazing Race'". Variety. Retrieved May 22, 2017.

- ↑ Rice, Lynette (April 18, 2018). "CBS renews 11 shows while Criminal Minds remains in limbo". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ↑ Serpe, Gina (October 24, 2007). "Amazing New Teams Rev to Race". E! News. Retrieved October 27, 2007.

- ↑ Perkins 2009, pp. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Miller, Gerri. "Inside The Amazing Race". How Stuff Works. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

- ↑ Tucker, Ken (February 11, 2009). "The Amazing Race (2009)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 25, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Pennington, Gail (February 20, 2011). "'Amazing Race' 18 goes high and wide". St. Louis Today. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- ↑ Kubicek, John (August 16, 2012). "'The Amazing Race' Raises the Prize to $2 Million for Season 21". BuddyTV. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ↑ Francescutti, Mark (December 8, 2014). "CBS's 'The Amazing Race' spotted in Dallas". Dallas News. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ "'Amazing Race' Kicks Off 27th Season At Venice Beach". CBS Los Angeles. June 22, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ↑ Hughes, William (November 11, 2015). "The Amazing Race is casting social media stars for this season's race". The A.V. Club. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ↑ Nordyke, Kimberly (June 15, 2016). "'Amazing Race's' Phil Keoghan on Close Calls, Superfan Encounters and How the Show Stays Fresh". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ "@AmazingRaceCBS new season just started in downtown LA. Story to come... #TAR #AmazingRace". Twitter. CelebSightings. June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ↑ Swartz, Tracy (July 3, 2016). "'The Amazing Race' films Season 29 in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Mitovich, Matt Webb (March 27, 2017). "NCIS and 24 Others Get Finale Dates at CBS — Which Might Be Series Finales?". TVLine. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ↑ Mitovich, Matt Webb (March 15, 2017). "Amazing Race Season 29 Cast: Meet the 22 Strangers Who Will Pair Up as Teams". TVLine. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ↑ Porreca, Brian (September 27, 2017). "'Big Brother' Fan Favorites to Compete on 'The Amazing Race' (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ Matt, Carter (October 27, 2017). "The Amazing Race 30 filming already over, Jessica Graf confirms". Carter Matt. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- 1 2 Keoghan, Phil (June 10, 2018). "Another #AmazingRace season has begun! Get ready to see some familiar faces on Season 31!". Twitter. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ↑ McCollum, Brian (July 3, 2018). "'Amazing Race' films in Detroit; teams rappel down Guardian Building". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ↑ Gennis, Sadie (May 4, 2018). "CBS May Do an All-Big Brother Edition of The Amazing Race". TV Guide. Retrieved June 2, 2018.

- 1 2 Berger, Warren (September 2, 2001). "COVER STORY; A Long Trip, With Someone You Know". New York Times. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Bloomenthal, Andrew (June 18, 2014). "'Amazing Race' Brain Trust Reveals Some Tricks to the Trade". Variety. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bloomenthal, Andrew (June 18, 2014). "'Amazing Race' Producers Leave a lot Up to Fate". Variety. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Petrozzello, Donna (September 4, 2001). "'Race' spans globe". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Shain, Michael (February 20, 2011). "'Egypt is off the map for us': Logan attack rumbles through primetime TV". New York Post. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Eakin, Marah (December 6, 2013). "What's it like to be a contestant on The Amazing Race". The A.V. Club. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ↑ O'Connell, Michael (September 13, 2012). "Emmys 2012: The 'Amazing Race' Creator Feared Cancellation Until Their First Win". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Lacher, Irene (September 30, 2012). "The Sunday Conversation: Bertram van Munster and Elise Doganieri of 'The Amazing Race'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 18, 2016.

- ↑ Wloszczyna, Susan (February 14, 2011). "Gnomes: Cute garden dwellers or little villains?". USA Today. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Snapple Partners With CBS on "The Amazing Race"" (Press release). Snapple. March 28, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ "U.S. Advertising Spending Declines 0.5% In First Half 2007, Nielsen Reports" (Press release). ACNeilsen. September 24, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ↑ Petrozzello, Donna (March 1, 2001). "CBS Picks Its Guide to Run the 'Race'". New York Daily News. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Racing up the ratings". The Age. Melbourne. May 5, 2005. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Miller, Martin (March 28, 2009). "'Amazing Race's' Phil Keoghan sets out to bike the USA". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ↑ "Father-Son Duo Closer After The Amazing Race". People. November 17, 2009. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ↑ Schinder, Michael (May 11, 2011). "Exclusive: Phil Keoghan Signs New Deal, Sticks With The Amazing Race". TV Guide. Retrieved May 11, 2011.

- ↑ "'Bowling Moms' answer lingering questions about the race". Movie Usenet. August 19, 2005. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- 1 2 Birnbaum, Debra (June 6, 2018). "Remote Controlled: 'Amazing Race' Bosses on Why 'Anybody' Can Win". Variety. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ↑ Warren, Michael (December 6, 2010). "Saving the world, one wedge at a time". Toronto Star. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ Zekas, Rita (May 22, 2000). "Amazing Race Goths are daredevils at heart". Toronto Star. Retrieved December 10, 2010.

- ↑ "Cowboy brothers ride 'Amazing Race' fame, run for office". Associated Press. June 12, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- 1 2 Hibberd, James (November 2, 2010). "Amazing Race Getting HD Upgrade". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 2, 2010.

- 1 2 Grey, Ellen (February 15, 2011). "Ellen Gray: Ex-'Race' contestants get another run - in HD". Philadelphia Daily News. Retrieved February 15, 2011.

- ↑ Lingo (February 11, 2005). "How is the whole visa situation handled?". The Amazing Race FAQ: Casting and Pre-Race Activities. TARflies Times. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- 1 2 Perkins 2009, pp. 13.

- ↑ Note: although one account suggested that cell phones could be borrowed in certain instances once the trip is underway.

- ↑ Boylan, Alex; Bernstein, Ryan. "The Day I...Won The Amazing Race". Hall of Fame Network. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ↑ Eng, Joyce (September 25, 2014). "8 Amazing Secrets From The Amazing Race Start Line". TV Guide. Retrieved May 17, 2016.

- ↑ Gray, Tim (July 11, 2018). "'Amazing Race,' 'Deadliest Catch' Audio Teams Detail Challenges in Capturing Sound". Variety. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ Perkins 2009, pp. 12.

- ↑ McLean, Thomas (July 20, 2010). "Great shots from rough spots". Variety. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Goldman, Eric (September 14, 2006). "IGN Interview: The Amazing Race's Phil Keoghan". IGN. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ↑ Lingo (February 11, 2005). "Where do the eliminated contestants go? I've heard of a place called "Sequesterville."". The Amazing Race FAQ: Eliminated Teams. TARflies Times. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rhodes, Joe (November 4, 2006). "An Audience Finally Catches Up to 'The Amazing Race'". New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2009.

- ↑ Perkins, Jr., Arthur (2009). Circumnavigating the Globe: Amazing Race 10 to 14 and Amazing Race Asia 1 to 3. AuthorHouse. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4490-1119-2. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "'20/20' tops 'Amazing Race' and 'Lost'". Media Life Magazine. September 6, 2001. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ↑ "CBS nips NBC in flick face-off". Media Life Magazine. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 "How did your favorite show rate?". USA Today. May 28, 2002. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Episode List: The Amazing Race". TV Tango. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- 1 2 "Nielsen's TOP 156 Shows for 2002-03". Groups.google.com. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ "'The Amazing Race 4' premiere draws best premiere ratings since 1st 'Race,' draws just under 10 million viewers". Reality TV World. May 30, 2003. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ↑ Sullivan, Brian Ford (September 30, 2003). "CBS gives fifth seasons to 'Amazing Race,' 'Big Brother'". The Futon Critic. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- ↑ "CBS' 'The Amazing Race 5' premiere delivers best ratings since 'The Amazing Race 3' finale". Reality TV World. August 7, 2004. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Episode List: The Amazing Race". TV Tango. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ CBS (October 20, 2004). "Eleven teams await the starting gun as the next "The Amazing Race" is about to begin". The Futon Critic.

- ↑ "SpotVault - The Amazing Race (CBS) - Fall 2004". Spotted Ratings. December 9, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "2004-05 Final audience and ratings figures". The Hollywood Reporter. May 27, 2005. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008.

- ↑ "CBS's 'The Amazing Race 7' finishes big, sets series ratings records". Reality TV World. November 5, 2005. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "2005-06 primetime wrap". The Hollywood Reporter. May 26, 2006. Archived from the original on April 23, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Episode List: The Amazing Race". TV Tango. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "2006-07 primetime wrap". The Hollywood Reporter. May 25, 2007. Archived from the original on January 29, 2010.

- ↑ Gorman, Bill (January 23, 2008). "Top CBS Primetime Shows, January 14–20". TV by the Numbers. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- 1 2 "Year end ratings, TAR vs. other hot shows. - alt.tv.amazing-race | Google Groups". Groups.google.com. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ Bierly, Mandi (September 29, 2008). "Ratings: 'Desperate Housewives' returns to win Sunday night". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 29, 2008.

- ↑ "The Finale of "The Amazing Race 13" Outruns "Race 12"". The Futon Critic. December 8, 2008. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 "ABC Medianet". ABC Medianet. May 19, 2009. Retrieved November 14, 2011.

- ↑ Seidman, Robert (February 16, 2009). "Sunday Ratings: Desperate Housewives leads a slow Sunday". TV by the Numbers. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ "CBS Winning Streak Hits 10". The Futon Critic. May 12, 2009. Retrieved May 12, 2010.

- ↑ "CBS wins premiere week in viewers and adults 25-54 - Ratings". TV by the Numbers. September 29, 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2012.