Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering

| |

| Abbreviation | FATF |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1989 |

| Type | Intergovernmental organization |

| Purpose | Combat money laundering and terrorism financing |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

Region served | Worldwide |

Membership | 37 |

Official language | English, French |

| Marshall Billingslea[1] | |

| Affiliations |

Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG) Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF) The Council of Europe Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures and the Financing of Terrorism (MONEYVAL) Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering in South America (GAFISUD) Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF) |

| Website |

www |

The Financial Action Task Force (on Money Laundering) (FATF), also known by its French name, Groupe d'action financière (GAFI), is an intergovernmental organization founded in 1989 on the initiative of the G7 to develop policies to combat money laundering. In 2001 its mandate expanded to include terrorism financing. It monitors progress in implementing the FATF Recommendations through "peer reviews" ("mutual evaluations") of member countries. The FATF Secretariat is housed at the OECD headquarters in Paris.

History

FATF was formed by the 1989 G7 Summit in Paris to combat the growing problem of money laundering. The task force was charged with studying money laundering trends, monitoring legislative, financial and law enforcement activities taken at the national and international level, reporting on compliance, and issuing recommendations and standards to combat money laundering. At the time of its formation, FATF had 16 members, which by 2016 had grown to 37.

In its first year, FATF issued a report containing forty recommendations to more effectively fight money laundering. These standards were revised in 2003 to reflect evolving patterns and techniques in money laundering.

The mandate of the organisation was expanded to include terrorist financing following the September 11 terror attacks in 2001.

The Forty Recommendations and Special Recommendations on Terrorism Financing

The FATF's primary policies issued are the Forty Recommendations on money laundering from 1990 [2] and the Nine Special Recommendations (SR) on Terrorism Financing (TF).[3]

Together, the Forty Recommendations and Special Recommendations on Terrorism Financing set the international standard for anti-money laundering measures and combating the financing of terrorism and terrorist acts. They set out the principles for action and allow countries a measure of flexibility in implementing these principles according to their particular circumstances and constitutional frameworks. Both sets of FATF Recommendations are intended to be implemented at the national level through legislation and other legally binding measures.[4]

The FATF completely revised the Forty Recommendations in 1996 and 2003.[2] The 2003 Forty Recommendations require states, among other things, to:

- Implement relevant international conventions

- Criminalise money laundering and enable authorities to confiscate the proceeds of money laundering

- Implement customer due diligence (e.g., identity verification), record keeping and suspicious transaction reporting requirements for financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions

- Establish a financial intelligence unit to receive and disseminate suspicious transaction reports, and

- Cooperate internationally in investigating and prosecuting money laundering

The FATF issued eight Special Recommendations on Terrorism Financing in October 2001, following the September 11 terrorist attacks in the United States. Among the measures, "Special Recommendation VIII" (SR VIII) was targeted specifically at nonprofit organizations. This was followed by the International Best Practices Combating the Abuse of Non-Profit Organizations in 2002, released one month before the U.S. Department of Treasury's Anti-Terrorist Financing Guidelines, and the Interpretive Note for SR VIII in 2006.

In February 2004 (Updated as of February 2009) the FATF published a reference document Methodology for Assessing Compliance with the FATF 40 Recommendations and the FATF 9 Special Recommendations.[5] The 2009 Handbook for Countries and Assessors outlines criteria for evaluating whether FATF standards are achieved in participating countries.[6] In February 2012, the FATF codified its recommendations and Interpretive Notes into one document that maintains SR VIII (renamed “Recommendation 8”), and also includes new rules on weapons of mass destruction, corruption and wire transfers (“Recommendation 16”).[7]

Non-cooperative countries or territories

In addition to FATF's "Forty plus Nine" Recommendations, in 2000 FATF issued a list of "Non-Cooperative Countries or Territories" (NCCTs), commonly called the FATF Blacklist. This was a list of 15 jurisdictions that, for one reason or another, FATF members believed were uncooperative with other jurisdictions in international efforts against money laundering (and, later, terrorism financing). Typically, this lack of cooperation manifested itself as an unwillingness or inability (frequently, a legal inability) to provide foreign law enforcement officials with information relating to bank account and brokerage records, and customer identification and beneficial owner information relating to such bank and brokerage accounts, shell company, and other financial vehicles commonly used in money laundering. As of October 2006, there are no Non-Cooperative Countries and Territories in the context of the NCCT initiative. However FATF issues updates as countries on High-risk and non-cooperative jurisdictions list have made significant improvements in standards and cooperation. The FATF also issues updates to identify additional jurisdictions that pose Money Laundering/Terrorist Financing risks.[8]

The effect of the FATF Blacklist has been significant, and arguably has proven more important in international efforts against money laundering than has the FATF Recommendations. While, under international law, the FATF Blacklist carried with it no formal sanction, in reality, a jurisdiction placed on the FATF Blacklist often found itself under intense financial pressure.[9]

Types of Members

Jurisdictions

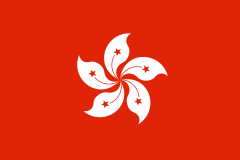

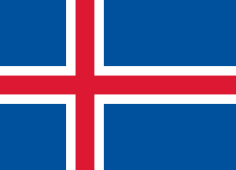

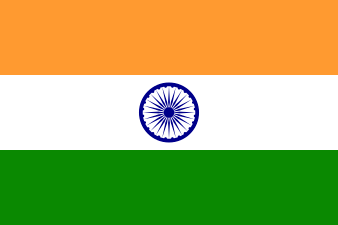

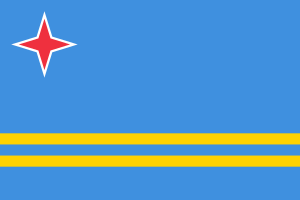

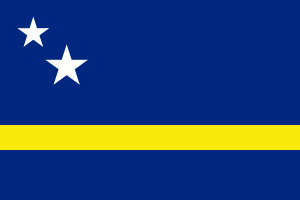

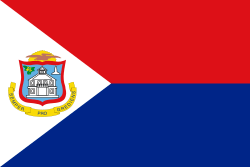

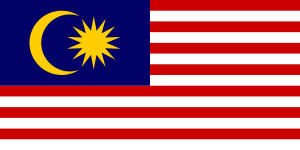

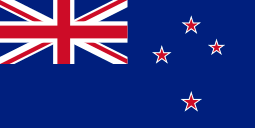

As of 2016 FATF consists of thirty-five member jurisdictions and two regional organisations, the European Commission and the Persian Gulf Co-operation Council. The FATF also works in close co-operation with a number of international and regional bodies involved in combating money laundering and terrorism financing.[10]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Associate members

As of 2015 there are 8 associate members:

- Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG)[11]

- Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF)[12]

- Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG)[13]

- Eurasian Group (EAG)[14]

- Council of Europe Select Committee of Experts on the Evaluation of Anti-Money Laundering Measures (MONEYVAL)(formerly PC-R-EV)[15]

- Financial Action Task Force of Latin America (GAFILAT), formerly The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering in South America (GAFISUD)[16]

- Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA)[17]

- Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF)[18]

Observer members

As of 2015 twenty five international organisations including for example the International Monetary Fund, the UN with six expert groups and the World Bank are observer organisations. The FATF welcomed the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as an observer to the FATF.

See also

References

- ↑ "FATF – Presidency". FATF-gafi.org. Retrieved 2018-06-30.

- 1 2 Archived August 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "National money laundering and terrorist financing risk assessment". FATF-GAFI. FATF-GAFI. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Methodology for Assessing Compliance with the FATF 40 Recommendations and the FATF 9 Special Recommendations" (PDF). FATF-GAFI.org. FATF-GAFI. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "AML/CFT Evaluations and Assessments" (PDF). FATF-GAFI. FATF-GAFI. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON COMBATING MONEY LAUNDERING AND THE FINANCING OF TERRORISM & PROLIFERATION. FATF Recommendations" (PDF). FATF/OECD. p. 130. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "High-risk and non-cooperative jurisdictions". FATF-GAFI. FATF-GAFI. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "Counter-Terrorism, "Policy Laundering," and the FATF: Legalizing Surveillance, Regulating Civil Society". The International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law. The International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- ↑ "FATF Members and Observers". FATF. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ↑ "Asia / Pacific Group On Money Laundering". Asia / Pacific Group. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Caribbean Financial Action Task Force". Caribbean Financial Action Task Force (CFATF). Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- ↑ "Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group-Home". Esaamlg.org. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ "The Eurasian Group on Combating Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism". Eurasiangroup.org. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ "Moneyval". Coe.int. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ↑ "GAFILAT". Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "GIABA - Welcome !". Giaba.org. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ↑ "MENAFATF Official Web Site". Menafatf.org. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

Further reading

- Hawala, An Informal Payment System and Its Use to Finance Terrorism by Sebastian R. Müller, December 2006, VDM Verlag, ISBN 3-86550-656-9, ISBN 978-3-86550-656-6

External links

- Official website

- Eurasian Group on Combating Money Laundering and Financing of Terrorism (EAG) FATF-Style Regional Bodies