Violent extremism

Violent extremism refers to the beliefs and actions of people who support or use ideologically motivated violence to achieve radical ideological, religious or political views.[1][2] Violent extremist views can be exhibited along a range of issues, including politics, religion and gender relations. No society, religious community or worldview is immune to violent extremism.[2] Though “radicalization” is a contested term to some, it has come to be used to define the process through which an individual or a group considers violence as a legitimate and a desirable means of action. Radical thought that does not condone the exercise of violence to further political goals may be seen as normal and acceptable, and be promoted by groups working within the boundaries of the law.[3] It is often used as a code name for Islamic terrorism.[4]

Causes

There is no single profile or pathway for radicalization, or even speed at which it happens.[5] Nor does the level of education seem to be a reliable predictor of vulnerability to radicalization. It is however established that there are socio-economic, psychological and institutional factors that lead to violent extremism. Specialists group these factors into three main categories, push factors, pull factors and contextual factors.[6][7][3]

Push factors

“Push Factors” drive individuals to violent extremism, such as: marginalization, inequality, discrimination, persecution or the perception thereof; limited access to quality and relevant education; the denial of rights and civil liberties; and other environmental, historical and socio-economic grievances.[3]

Pull factors

“Pull Factors” nurture the appeal of violent extremism, for example: the existence of well-organized violent extremist groups with compelling discourses and effective programmes that are providing services, revenue and/or employment in exchange for membership. Groups can also lure new members by providing outlets for grievances and promise of adventure and freedom. Furthermore, these groups appear to offer spiritual comfort, “a place to belong” and a supportive social network.[3]

Contextual factors

Contextual factors that provide a favourable terrain to the emergence of violent extremist groups, such as: fragile states, the lack of rule of law, corruption and criminality.

The following behaviours in combination have been identified as signs of potential radicalization:[8][3]

- Sudden break with the family and long-standing friendships.

- Sudden drop-out of school and conflicts with the school.

- Change in behaviour relating to food, clothing, language or finances.

- Changes in attitudes and behaviour towards others: antisocial comments, rejection of authority, refusal to interact socially, signs of withdrawal and isolation.

- Regular viewing of internet sites and participation in social media networks that condone radical or extremist views.

- Reference to apocalyptic and conspiracy theories.

Prevention of radicalisation and deradicalisation

Education

The role of education in preventing violent extremism and de-radicalizing young people has only recently gained global acceptance. An important step in this direction was the launch, in December 2015, of the UN Secretary-General’s Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism which recognizes the importance of quality education to address the drivers of this phenomenon.[9][3]

The United Nations Security Council also emphasized this point in its Resolutions 2178 and 2250, which notably highlights the need for “quality education for peace that equips youth with the ability to engage constructively in civic structures and inclusive political processes” and called on “ all relevant actors to consider instituting mechanisms to promote a culture of peace, tolerance, intercultural and interreligious dialogue that involve youth and discourage their participation in acts of violence, terrorism, xenophobia, and all forms of discrimination.”[10]

Education has been identified as preventing radicalisation through:[3]

- Developing the communication and interpersonal skills they need to dialogue, face disagreement and learn peaceful approaches to change.

- Developing critical thinking to investigate claims, verify rumours and question the legitimacy and appeal of extremist beliefs.

- Developing resilience to resist extremist narratives and acquire the social-emotional skills they need to overcome their doubts and engage constructively in society without having to resort to violence.

- Fostering critically informed citizens able to constructively engage in peaceful collective action.

UNESCO has emphasised Global Citizenship Education (GCED) as an emerging approach to education that focuses on developing learners’ knowledge, skills, values and attitudes in view of their active participation in the peaceful and sustainable development of their societies. GCED aims to instill respect for human rights, social justice, gender equality and environmental sustainability, which are fundamental values that help raise the defences of peace against violent extremism.[11][12][3]

Sabaoon Project, Pakistan

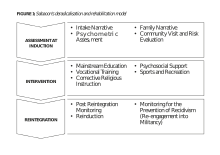

The Sabaoon Project, initiated by the Pakistan Army and run by the Social Welfare Academics and Training organization (SWAaT) since 2009, has been implemented to deradicalize and rehabilitate former militant youth who were involved in violent extremist activities and apprehended by the army in Swat and the surrounding areas in Pakistan. Based on an individualized approach and intervention, the project follows a three-step model (see image).[13]

Kenya’s initiatives to address radicalization of youth in educational institutions

To tackle the issue of violent extremism and radicalization in schools, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of Kenya launched a new national strategy targeting youth in 2014, entitled Initiatives to Address Radicalization of the Youth in Educational Institutions in the Republic of Kenya. The Strategy adopted measures that service the students’ interests and well-being. For example, it includes efforts to create child-friendly school environments and encourages students to participate in “talent academies” to pursue an area of their own interest.[13]

The Strategy also includes the discontinuation of ranking schools based on academic performance. This was to lessen the overemphasis on examinations and to reduce student pressure, incorporating other indicators of student achievement, such as abilities in sport and artistic talent. The purpose is to reduce the stress of students’ lives at home and in school that may be vented through escape tactics, including joining outlawed groups. The Strategy also employs other effective means to prevent violent extremism, including the integration of Preventing of Violent Extremism through Education (PVE-E) in curricula and school programmes; adopting a multi- sectoral and multi-stakeholder approach; encouraging student participation through student governance processes and peer-to-peer education; and the involvement of media as a stakeholder.[13]

Gender disparity

While it is being increasingly reported that women play an active role in violent extremist organizations and attacks as assailants and supporters, men are still more often the perpetrators of violent extremist acts and therefore the targets of recruitment campaigns.[14][15][13]

See also

Sources

![]()

![]()

References

- ↑ "Countering Violent Extremism | Homeland Security". www.dhs.gov. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- 1 2 "Living Safe Together Home". www.livingsafetogether.gov.au. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "A Teacher's Guide on the Prevention of Violent Extremism" (PDF). UNESCO.

- ↑ Beinart, Peter. "The Real Reason Obama Avoids the Phrase 'Radical Islam'".

- ↑ Davies, Lynn. "Educating against Extremism: Towards a Critical Politicisation of Young People". International Review of Education. 55: 183–203. doi:10.1007/s11159-008-9126-8. ISSN 0020-8566.

- ↑ "USAID Summary of Factors Effecting Violent Extremism" (PDF). USAID.

- ↑ Younis, Sara Zeiger, Anne Aly, Peter R. Neumann, Hamed El Said, Martine Zeuthen, Peter Romaniuk, Mariya Y. Omelicheva, James O. Ellis, Alex P. Schmid, Kosta Lucas, Thomas K. Samuel, Clarke R. Jones, Orla Lynch, Ines Marchand, Myriam Denov, Daniel Koehler, Michael J. Williams, John G. Horgan, William P. Evans, Stevan Weine, Ahmed (2015-09-22). "Countering violent extremism: developing an evidence-base for policy and practice". Australian Policy Online. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- ↑ "Stop-Djihadisme". Stop-Djihadisme. Retrieved 2016-12-06.

- ↑ "Plan of Action to Prevent Violent Extremism. Report of the Secretary-General" (PDF). United Nations.

- ↑ "UN Security Council Resolution 2250, adopted in December 2015" (PDF). United Nations.

- ↑ "Global Citizenship Education – Topics and Learning Objectives" (PDF). UNESCO.

- ↑ "Global Citizenship Education - Preparing learners for the challenges of the twenty-first century" (PDF). UNESCO.

- 1 2 3 4 UNESCO (2017). Preventing violent extremism through education: A guide for policy makers (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 24, 36, 41. ISBN 978-92-3-100215-1.

- ↑ B. Carter, 2013; Women and violent extremism, GSDRC. http://www.gsdrc.org/docs/open/ hdq898.pdf Accessed on 2 November 2016.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N00/720/18/PDF/N0072018. pdf?OpenElement Accessed on 1 December 2016.