Tax haven

A tax haven is generally defined as a country or place with very low "effective" rates of taxation for foreigners ("headline" rates may be higher[lower-alpha 1]).[1][2][3][4][5] In some traditional definitions, a tax haven also offers financial secrecy.[lower-alpha 2][6] However, while countries with high levels of secrecy but also high rates of taxation (e.g. the United States and Germany in the Financial Secrecy Index ("FSI") rankings),[lower-alpha 3] can feature in some tax haven lists, they are not universally considered as tax havens. In contrast, countries with lower levels of secrecy but also low "effective" rates of taxation (e.g. Ireland in the FSI rankings), appear in most § Tax haven lists.[9] The consensus around effective tax rates has led academics to note that the term "tax haven" and "offshore financial centre" are almost synonymous.[10]

Traditional tax havens, like Jersey, are open about zero rates of taxation, but as a consequence have limited bilateral tax treaties. Modern corporate tax havens have non-zero "headline" rates of taxation and high levels of OECD-compliance, and thus have large networks of bilateral tax treaties. However, their base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") tools enable corporates to achieve "effective" tax rates closer to zero, not just in the haven but in all countries with which the haven has tax treaties; putting them on tax haven lists. According to modern studies, the § Top 10 tax havens include corporate-focused havens like Ireland, the Netherlands, Singapore, and the U.K., while Switzerland, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, and the Caribbean (the Caymans, Bermuda, and the British Virgin Islands), feature as both major traditional tax havens and major corporate tax havens. Corporate tax havens often serve as "conduits" to traditional tax havens.[11][12][13]

Use of tax havens, traditional and corporate, results in a loss of tax revenues to countries which are not tax havens. Estimates of total amounts of taxes avoided vary, but the most credible have a range of US$100–250 billion per annum.[14][15][16] In addition, capital held in tax havens can permanently leave the tax base (base erosion). Estimates of capital held in tax havens also vary: the most credible estimates are between $7–10 trillion (up to 10% of global assets).[17] The harm of traditional and corporate tax havens has been particularly noted in developing nations, where the tax revenues are needed to build infrastructure.[18]

At least 15%[lower-alpha 4] of countries are tax havens.[4][9] Tax havens are mostly successful and well-governed economies, and being a haven has often brought prosperity.[21][22] The top 10–15 GDP-per-capita countries, excluding oil and gas exporters, are tax havens. Because of § Inflated GDP-per-capita (due to accounting BEPS flows), havens are prone to over-leverage (international capital misprice the artificial debt-to-GDP). This can lead to severe credit cycles and/or property/banking crises when international capital flows are repriced. Ireland's Celtic Tiger, and the subsequent financial crisis in 2009–13, is an example.[23] Jersey is another.[24] Research shows the § U.S. as the largest beneficiary, and U.S. multinational use of tax havens, has maximised long-term U.S. exchequer receipts;[25] however experts note OECD jurisdictions accommodated the U.S. to overcome shortcomings in the U.S. "worldwide" tax system (others use "territorial" systems, and don't need havens).

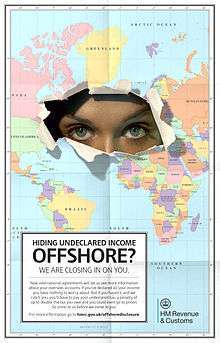

The focus on combating tax havens (e.g. OECD-IMF projects) has been on common standards, transparency and data sharing.[26] The rise of OECD-compliant corporate tax havens, whose BEPS tools are responsible for most of the quantum of lost taxes,[16] has led to criticism of this focus, versus actual taxes paid.[27] Higher-tax jurisdictions, such as the United States and many member states of the European Union, departed from the OCED BEPS Project in 2017–18, to introduce anti-BEPS tax regimes, targeted raising net taxes paid by corporations in corporate tax havens (e.g. the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") GILTI-BEAT-FDII tax regimes and move to a hybrid "territorial" tax system, and the proposed EU Digital Services Tax regime and the proposed EU Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base).

Definitions

The consensus regarding a specific and exact definition of what constitutes a tax haven, is that there is none. This is the conclusion from non-governmental organisations, such as the Tax Justice Network,[30] from the 2008 investigation by the U.S. Government Accountability Office,[31] from the 2015 investigation by the U.S. Congressional Research Service,[32] from the 2017 investigation by the European Parliament,[33] and from leading academic researchers of tax havens.[34]

The issue, however, is material, as being labelled a "tax haven" has consequences for a country seeking to develop and trade under bilateral tax treaties. When Ireland was "blacklisted" by G20 member Brazil in 2016, bilateral trade declined.[35][36] It is even more onerous for corporate tax havens, whose foreign multinationals rely on the haven's extensive network of bilateral tax treaties, through which the foreign multinationals execute BEPS transactions, re-routing global untaxed income to the haven.

One of the first § Important papers on tax havens,[37] was the 1994 Hines-Rice paper by James R. Hines Jr.[38] It is the most cited paper on tax haven research,[28] even in late 2017,[29] and Hines is the most cited author on tax haven research.[28] As well as offering insights into tax havens, it took the view that the diversity of countries that become tax havens was so great that detailed definitions were inappropriate. Hines merely noted that tax havens were: a group of countries with unusually low tax rates. Hines reaffirmed this approach in a 2009 paper with Dhammika Dharmapala.[4] He refined it in 2016 to incorporate research on § Incentives for tax havens on governance, which is broadly accepted in the academic lexicon.[10][39][37]

Tax havens are typically small, well-governed states that impose low or zero tax rates on foreign investors.

— James R. Hines Jr. "Multinational Firms and Tax Havens", The Review of Economics and Statistics (2016)[5]

In April 1998, the OECD produced a definition of a tax haven, as meeting "three of four" criteria.[40][41] It was produced as part of their "Harmful Tax Competition: An Emerging Global Issue" initiative.[42] By 2000, when the OECD published their first list of tax havens,[19] it included no OECD member countries as they were now all considered to have engaged in the OECD's new Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes, and therefore would not meet Criteria ii and Criteria iii. Because the OECD has never listed any of its 35 members as tax havens, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Switzerland are sometimes defined as the "OECD tax havens".[43] In 2017, only Trinidad & Tobago met the 1998 OECD definition, and it has fallen into disrepute.[44][45][46]

- No or nominal tax on the relevant income;

- Lack of effective exchange of information;

- Lack of transparency;

- No substantial activities (e.g. tolerance of brass plate companies).†

(†) The 4th criterion was withdrawn after objections from the new U.S. Bush Administration in 2001,[26] and in the OECD's 2002 report the definition became "two of three criteria".[9]

The 1998 OECD definition is most frequently invoked by the "OECD tax havens".[47] However, it has been discounted by tax haven academics,[34][39][48] including the 2015 U.S. Congressional Research Service investigation into tax havens, as being restrictive, and enabling Hines’ low-tax havens (e.g. to which the first criterion applies), to avoid the OECD definition by improving OECD corporation (so the second and third criteria do not apply).[32]

Thus, the evidence (limited though it undoubtedly is) does not suggest any impact of the OECD initiative on tax-haven activity. [..] Thus, the OECD initiative cannot be expected to have much impact on corporate uses of tax havens, even if (or when) the initiative is fully implemented

— Dhammika Dharmapala, "What Problems and Opportunities are created by Tax Havens?" (December 2008)[34]

In April 2000, the Financial Stability Forum (or FSF) defined the related concept of an offshore financial centre (or OFC),[49] which the IMF adopted in June 2000.[50] An OFC is similar to a "tax haven" and the terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but the term OFC is less controversial and pejorative.[10][51][52] The FSF-IMF definition focused on the BEPS tools havens offer, and on Hines' observation that the accounting flows from BEPS tools distort the economic statistics of the haven. The FSF-IMF list captured new corporate tax havens, such as the Netherlands, which Hines considered too small in 1994.[9]

In December 2008, Dharmapala wrote that the OECD process had removed much of the need to include "bank secrecy" in any definition of a tax haven and that it was now "first and foremost, low or zero corporate tax rates",[34] and this has become the general "financial dictionary" definition of a tax haven.[1][2][3]

In October 2009, the Tax Justice Network introduced the Financial Secrecy Index ("FSI") and the term "secrecy jurisdiction",[30] to highlight issues in regard to OECD-compliant countries who have high tax rates and do not appear on academic lists of tax havens, but have transparency issues. The FSI does not assess tax rates or BEPS flows in its calculation; but it is often misinterpreted as a tax haven definition in the financial media,[lower-alpha 3] particularly when it lists the USA and Germany as major "secrecy jurisdictions".[53][54][55] However, many types of tax havens also rank as secrecy jurisdictions.

In October 2010, Hines published a list of 52 tax havens, scaled by analysing corporate investment flows.[20] Hines' largest havens were dominated by corporate tax havens, who Dharmapala noted in 2014 accounted for the bulk of global tax haven activity from BEPS tools.[56] The Hines 2010 list was the first to estimate the ten largest global tax havens, only two of which, Jersey and the British Virgin Isles, were on the OECD’s 2000 list.

In July 2017, the University of Amsterdam's CORPNET group ignored any definition of a tax haven and focused on a purely quantitive approach, analysing 98 million global corporate connections on the Orbis database. CORPNET's lists of top five Conduit OFCs, and top five Sink OFCs, matched 9 of the top 10 havens in Hines' 2010 list, only differing in the United Kingdom, which only transformed their tax code in 2009-12. CORPNET's Conduit and Sink OFCs study split the understanding of a tax haven into two classifications:[57]

- 24 Sink OFCs: jurisdictions in which a disproportionate amount of value disappears from the economic system (e.g. the traditional tax havens).

- 5 Conduit OFCs: jurisdictions through which a disproportionate amount of value moves toward sink OFCs (e.g. the modern corporate tax havens).

In June 2018, tax academic Gabriel Zucman (et alia) published research that also ignored any definition of a tax haven, but estimated the corporate "profit shifting" (i.e. BEPS), and "enhanced corporate profitability" that Hines and Dharmapala had noted.[58] Zucman pointed out that the CORPNET research under-represented havens associated with US technology firms, like Ireland and the Cayman Islands, as Google, Facebook and Apple do not appear on Orbis.[59] Even so, Zucman's 2018 list of top 10 havens also matched 9 of the top 10 havens in Hines' 2010 list, but with Ireland as the largest global haven.[60] These lists (Hines 2010, CORPNET 2017 and Zucman 2018), and others, which followed a purely quantitive approach, showed a firm consensus around the largest corporate tax havens.

Tax haven lists

Types of lists

Three main types of tax haven lists have been produced to date:[32]

- Governmental, Qualitative: these lists are qualitative and political;[61] they never list members (or each other), and are largely disregarded by academic research;[34][48] the OECD had one country on its 2017 list, Trinidad & Tobago; the EU had 17 countries on its 2017 list,[62] none of which were OECD or EU countries, or § Top 10 tax havens.[63][64]

- Non-governmental, Qualitative: these follow a subjective scoring system based on various attributes (e.g. type of tax structures available in the haven); the best known are Oxfam's Corporate Tax Havens list,[65][66] and the Financial Secrecy Index (although the FSI is a list of "financial secrecy jurisdictions", and not specifically tax havens).[lower-alpha 3]

- Non-governmental, Quantitative: by following an objective quantitative approach, they can rank the relative scale of individual havens; the best known are:

- Tax rate – focus on effective tax rates, like the Hines-Rice 1994 list,[38] and the Dharmapala-Hines 2009 list.[4] (Hines and Dharmapala avoided rankings in these lists).

- Connections – focus on legal connections, either Orbis connections like CORPNET's 2017 Conduit and Sink OFCs, or subsidiary connections like the ITEP Connections 2017 list.[67]

- Quantum – focus on profits shifted, either BEPS flows like the Zucman-Tørsløv-Wier 2018 list,[58][68] FDI flows like the James Hines 2010 list,[20] or Profits like the ITEP Profits 2017 list.[lower-alpha 6][67]

Research also highlights proxy indicators, of which the two most prominent are:

- U.S. tax inversions – A basic "sense-check" of a tax haven is whether individuals or corporates relocate there to avoid taxes (i.e. why accusations of the U.S. as a tax haven are not considered credible). While individual relocations are hard to track, corporations are easier. The top 3 destinations for all U.S. corporate tax inversions since 1982 are: Ireland (#1), Bermuda (#2) and the U.K. (#3);[69]

- GDP-per-capita tables – Another effective "sense-check" of a tax haven is distortion in its GDP/GNP from the IP-based BEPS tools and Debt-based BEPS tools. Excluding the non-oil & gas nations (e.g. Qatar, Norway), and micro jurisdictions, the resulting highest GDP-per-capita countries are tax havens, led by: Luxembourg (#1), Singapore (#2), and Ireland (#3).

Top 10 tax havens

The post-2010 rise in quantitative techniques of identifying tax havens has seen a consistency amongst the ten largest tax havens. Dharmapala notes that as corporate BEPS flows dominate tax haven activity, these are mostly corporate tax havens.[56] Nine of the top ten tax havens in Gabriel Zucman's June 2018 study appear in the top ten lists of the two other quantitative studies since 2010. Four of the top five Conduit OFCs are represented; however, the United Kingdom only transformed its tax code in 2009-2012. All five of the top 5 Sink OFCs are represented, although Jersey only appears in the Hines 2010 list.

The studies capture the rise of Ireland and Singapore, both major regional headquarters for some of the largest BEPS tool users, Apple, Google and Facebook.[70][71][72]

In Q1 2015, Apple completed the largest BEPS action in history, when it shifted USD 300 billion of IP to Ireland, which Nobel-prize economist Paul Krugman called "leprechaun economics".

In September 2018, using TCJA repatriation tax data, the NBER listed the key tax havens as: "Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda and [the] Caribbean havens".[73][74]

| List | Hines 2010[20] | ITEP 2017[lower-alpha 6][67] | Zucman 2018[58] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum | FDI | Profits | BEPS |

| Rank | |||

| 1 | Luxembourg*‡ | Netherlands*† | Ireland*† |

| 2 | Cayman Islands* | Ireland*† | Caribbean: Cayman Islands* & British Virgin Islands*‡Δ |

| 3 | Ireland*† | Bermuda*‡ | Singapore*† |

| 4 | Switzerland*† | Luxembourg*‡ | Switzerland*† |

| 5 | Bermuda*‡ | Cayman Islands* | Netherlands*† |

| 6 | Hong Kong*‡ | Switzerland*† | Luxembourg*‡ |

| 7 | Jersey‡Δ | Singapore*† | Puerto Rico |

| 8 | Netherlands*† | BahamasΔ | Hong Kong*‡ |

| 9 | Singapore*† | Hong Kong*‡ | Bermuda*‡ |

| 10 | British Virgin Islands*‡Δ | British Virgin Islands*‡Δ | (n.a. as "Caribbean" contains 2 havens) |

(*) Appears as a top ten tax haven in all three lists; 9 major tax havens meet this criterion, Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland and the Netherlands (the Conduit OFCs), and the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong and Bermuda (the Sink OFCs).

(†) Also appears as one of 5 Conduit OFC (Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom), in CORPNET's 2017 research; or

(‡) Also appears as a Top 5 Sink OFC (British Virgin Islands, Luxemburg, Hong Kong, Jersey, Bermuda), in CORPNET's 2017 research.

(Δ) Identified on the first, and largest, OECD 2000 list of 35 tax havens (the OECD list only contained Trinidad & Tobago by 2017).[19]

The strongest consensus amongst academics regarding the world's largest tax havens is therefore: Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland and the Netherlands (the major Conduit OFCs), and the Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands, Luxembourg, Hong Kong and Bermuda (the major Sink OFCs), with the United Kingdom (a major Conduit OFC) still in transformation.

Of these ten major havens, all except the United Kingdom and the Netherlands featured on the original Hines-Rice 1994 list. The United Kingdom was not a tax haven in 1994, and Hines estimated the Netherlands's effective tax rate in 1994 at over 20% (he estimated Ireland’s at 4%). Four of them, Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland (3 of the 5 top Conduit OFCs), and Hong Kong (a top 5 Sink OFC), featured in the Hines-Rice 1994 list's 7 major tax havens sub-category; highlighting a lack of progress in curtailing tax havens.[38]

In terms of proxy indicators, this list, excluding Canada, contains all seven of the countries that received more than one US tax inversion since 1982 (see here)[69]. In addition, six of these major tax havens are in the top 15 GDP-per-capita, and of the four others, three of them, the Caribbean locations, are not included in IMF-World Bank GDP-per-capita tables.

In a June 2018 joint IMF report into the effect of BEPS flows on global economic data, eight of the above (excluding Switzerland and the United Kingdon) were cited as the world’s leading tax havens.[75]

Top 20 tax havens

The longest list from Non-governmental, Quantitative research on tax havens is the University of Amsterdam CORPNET July 2017 Conduit and Sink OFCs study, at 29 (5 Conduit OFCs and 25 Sink OFCs). The following are the 20 largest (5 Conduit OFCs and 15 Sink OFCs), which reconcile with other main lists as follows:

(*) Appears in as a § Top 10 tax haven in all three quantitative lists, Hines 2010, ITEP 2017 and Zucman 2018 (above); all nine such § Top 10 tax havens are listed below.

(♣) Appears on the James Hines 2010 list of 52 tax havens; seventeen of the twenty locations below, are on the James Hines 2010 list.

(Δ) Identified on the largest OECD 2000 list of 35 tax havens (the OECD list only contained Trinidad & Tobago by 2017); only four locations below were ever on an OECD list.[19]

(↕) Identified on the European Union's first 2017 list of 17 tax havens;[62] only one location below is on the EU 2017 list.

Sovereign states that feature mainly as major corporate tax havens are:

- *♣Ireland – a major corporate tax haven, and ranked by tax academics as the largest;[74][15][76][68] leader in IP-based BEPS tools (e.g. double Irish), but also Debt-based BEPS tools.[77][69]

- *♣Singapore – the major corporate tax haven for Asia (APAC headquarters for most US technology firms), and key conduit to core Asian Sink OFCs, Hong Kong and Taiwan.[78]

- *♣Netherlands – a major corporate tax haven,[11] and the largest Conduit OFC via its IP-based BEPS tools (e.g. Dutch Sandwich); traditional leader in Debt-based BEPS tools.[79][80]

- United Kingdom – rising corporate tax haven after restructuring tax code in 2009–12; 17 of the 24 Sink OFCs are former, or current, dependencies of the U.K. (see Sink OFC table)[12][69]

Sovereign states that feature as both major corporate tax havens and major traditional tax havens, include:

- *♣Switzerland – both a major traditional tax haven (or Sink OFC), and a major corporate tax haven (or Conduit OFC), and strongly linked to major Sink OFC, Jersey.

- *♣Luxembourg – one of the largest Sink OFCs in the world (a terminus for many corporate tax havens, especially Ireland and the Netherlands).[81]

- *♣Hong Kong – the "Luxembourg of Asia", and almost as large a Sink OFC as Luxembourg; tied to APAC's largest corporate tax haven, Singapore.

.svg.png)

Sovereign or semi-sovereign states that feature mainly as traditional tax havens (but have non-zero tax rates), include:

- ♣Cyprus – damaged its reputation during the financial crisis when the Cypriot banking system nearly collapsed, however reappearing in top 10 lists.[65]

- Taiwan – major traditional tax haven for APAC, and described by the Tax Justice Network as the "Switzerland of Asia".[82]

- ♣Malta – an emerging tax haven inside the EU,[83][84] which has been a target of wider media scrutiny.[85]

Sub-national states that are very traditional tax havens (i.e. explicit 0% rate of tax) include (fuller list in table opposite):

- ♣ΔJersey (United Kingdom dependency),[86] still a major traditional tax haven; the CORPNET research identifies a very strong connection with Conduit OFC Switzerland (e.g. Switzerland is increasingly relying on Jersey as a traditional tax haven); issues of financial stability.[24]

- (♣ΔIsle of Man (United Kingdom dependency), the "failing tax haven",[87] not in the CORPNET study (discussed here), but included for completeness.)

- Current British Overseas Territories, see table opposite, where 17 of the 24 Sink OFCs, are current or past, U.K. dependencies:

- *♣ΔBritish Virgin Islands, largest Sink OFC in the world and regularly appears alongside the Caymans and Bermuda (the Caribbean "triad") as a group.[88][89]

- *♣Bermuda,[90] does feature as a U.S. corporate tax haven; only 2nd to Ireland as a destination for U.S. tax inversions.[69]

- *♣Cayman Islands,[91] also features as a major U.S. corporate tax haven; 6th most popular destination for U.S. corporate tax inversions.[69]

- ♣ΔGibraltar – like the Isle of Man, has declined due to concerns, even by the U.K., over its practices.[92]

- ♣Mauritius – has become a major tax haven for both SE Asia (especially India) and African economies, and now ranking 8th overall.[93][94]

- Curacao – the Dutch dependency ranked 8th on the Oxfam's tax haven list, and the 12th largest Sink OFC, and recently made the EU's greylist.[95]

- ♣ΔLiechtenstein – long-established very traditional European tax haven and just outside of the top 10 global Sink OFCs.[96]

- ♣ΔBahamas – acts as both a traditional tax haven (ranked 12th Sink OFC), and ranks 8th on the ITEP profits list (figure 4, page 16)[67] of corporate havens; 3rd highest secrecy score on the FSI.

- ♣Δ↕Samoa – a traditional tax haven (ranked 14th Sink OFC), used to have one of the highest secrecy scores on the FSI, since reduced moderately.[97]

Broad lists of tax havens

Post-2010 research on tax havens is focused on quantitative analysis (which can be ranked), and tends to ignore very small tax havens where data is limited as the haven is used for individual tax avoidance rather than corporate tax avoidance. The last credible broad unranked list of global tax havens is the James Hines 2010 list of 52 tax havens. It is shown below but expanded to 55 to include havens identified in the July 2017 Conduit and Sink OFCs study that were not considered havens in 2010, namely the United Kingdom, Taiwan, and Curaçao. The James Hines 2010 list contains 34 of the original 35 OCED tax havens;[19] and compared with the § Top 10 tax havens and § Top 20 tax havens above, show OECD processes focus on the compliance of tiny havens.

- AndorraΔ

- Anguilla‡Δ

- Antigua and BarbudaΔ

- ArubaΔ

- Bahamas‡Δ

- Bahrain↕Δ

- Barbados↕Δ

- Belize‡Δ

- Bermuda‡

- British Virgin Islands‡Δ

- Cayman Islands‡

- Cook IslandsΔ

- Costa Rica

- [Curacao‡] not on Hines list

- Cyprus‡

- Djibouti

- DominicaΔ

- Gibraltar‡Δ

- Grenada↕Δ

- GuernseyΔ

- Hong Kong‡

- Ireland†

- Isle of ManΔ

- Jersey‡Δ

- Jordan

- Lebanon

- Liberia‡Δ

- Liechtenstein‡Δ

- Luxembourg‡

- Macao↕

- MaldivesΔ

- Malta‡

- Marshall Islands‡↕Δ

- Mauritius‡

- Micronesia

- Monaco‡Δ

- MontserratΔ

- Nauru‡Δ

- Netherlands† & AntillesΔ

- NiueΔ

- Panama↕Δ

- Samoa‡↕Δ

- San Marino

- Seychelles‡Δ

- Singapore†

- St. Kitts and NevisΔ

- St. Lucia↕Δ

- St. Martin

- St. Vincent and the Grendines‡Δ

- Switzerland†

- [Taiwan‡] not on Hines list

- TongaΔ

- Turks and CaicosΔ

- [United Kingdom†] not on Hines list

- VanuatuΔ

(†) Identified as one of the 5 Conduits by CORPNET in 2017; the above list has 5 of the 5.

(‡) Identified as one of the largest 24 Sinks by CORPNET in 2017; the above list has 23 of the 24 (Guyana missing).

(↕) Identified on the European Union's first 2017 list of 17 tax havens; the above list contains 8 of the 17.[62]

(Δ) Identified on the first, and the largest, OECD 2000 list of 35 tax havens (the OECD list only contained Trinidad & Tobago by 2017); the above list contains 34 of the 35 (U.S. Virgin Islands missing).[19]

Unusual cases

U.S. dedicated entities:

- Delaware (United States), a unique "onshore" specialised haven with very strong secrecy laws.[98]

- Puerto Rico (United States), almost a corporate tax haven "concession" by the U.S.,[99] but which the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 mostly removes.[100]

Major sovereign States which feature on financial secrecy lists (e.g. the Financial Secrecy Index), but not on corporate tax haven or traditional tax haven lists, are:

- United States – noted for secrecy, per the Financial Secrecy Index, (see United States as a tax haven); makes a "controversial" appearance on some lists.[53]

- Germany – similar to the U.S., Germany can be included on lists for its tax secrecy, per the Financial Secrecy Index[101]

Neither the U.S. or Germany have appeared on any tax haven lists by the main academic leaders in tax haven research, namely: James R. Hines Jr., Dhammika Dharmapala or Gabriel Zucman. There are no known cases of foreign firms executing tax inversions to the U.S. or Germany for tax purposes, a basic sense-check of a corporate tax haven.[69]

Former tax havens

- Beirut, Lebanon formerly had a reputation as the only tax haven in the Middle East. However, this changed after the Intra Bank crash of 1966,[102] and the subsequent political and military deterioration of Lebanon dissuaded foreign use of the country as a tax haven.

- Liberia had a prosperous ship registration industry. The series of violent and bloody civil wars in the 1990s and early 2000s severely damaged confidence in the country. The fact that the ship registration business still continues is partly a testament to its early success, and partly a testament to moving the national shipping registry to New York, United States.

- Tangier had a short existence as a tax haven in the period between the end of effective control by the Spanish in 1945 until it was formally reunited with Morocco in 1956.

- Some Pacific islands were tax havens but were curtailed by OECD demands for regulation and transparency in the late 1990s, on the threat of blacklisting. Vanuatu's Financial Services commissioner said in May 2008 that his country would reform laws and cease being a tax haven. "We've been associated with this stigma for a long time and we now aim to get away from being a tax haven."[103][104]

Financial effect

Capital held offshore

| Individuals with financial assets ($millions) |

Total liquid net worth ($trillions) |

Amount of which offshore ($trillions) |

|---|---|---|

| Over 30 | $16.7 | $9.8 |

| 5 to 30 | $10.7 | $5.1 |

| 1 to 5 | $17.4 | $4.7 |

| All above 1 | $44.8 | $19.6 |

| Under 1 | $10.3 | $1.0 |

| Total | $55.1 | $20.6 |

While incomplete, and with the limitations discussed below, the available statistics nonetheless indicate that offshore banking is a very sizable activity. The OECD estimated in 2007 that capital held offshore amounted to between $5 trillion and $7 trillion, making up approximately 6–8% of total global investments under management.[106]

A more recent study by Gabriel Zucman of the London School of Economics estimated the amount of global cross-border wealth held in tax havens (including the Netherlands and Luxembourg as tax havens for this purpose) at US$7.6 trillion, of which US$2.46 trillion was held in Switzerland alone.[17][18] The Tax Justice Network (an anti-tax haven pressure group) estimated in 2012 that capital held offshore amounted to between $21 trillion and $32 trillion (between 24–32% of total global investments),[107][108][109] although those estimates have been challenged.[110]

In 2000, the International Monetary Fund calculated based on Bank for International Settlements data that for selected offshore financial centres, on-balance sheet cross-border assets held in offshore financial centres reached a level of $4.6 trillion at the end of June 1999 (about 50 percent of total cross-border assets). Of that $4.6 trillion, $0.9 trillion was held in the Caribbean, $1 trillion in Asia, and most of the remaining $2.7 trillion accounted for by the major international finance centres (IFCs), namely London, the U.S. IBFs, and the Japanese offshore market.[111] The U.S. Department of Treasury estimated that in 2011 the Caribbean Banking Centers, which include Bahamas, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Netherlands Antilles and Panama, held almost $2 trillion in United States debt.[112] Of this, approximately US$1.4 trillion is estimated to be held in the Cayman Islands alone.[106]

The Wall Street Journal in a study of 60 large U.S. companies found that they deposited $166 billion in offshore accounts in 2012, sheltering over 40% of their profits from U.S. taxes.[113] Similarly, Desai, Foley and Hines found that: "in 1999, 59% of U.S. firms with significant foreign operations had affiliates in tax haven countries", although they did not define "significant" for this purpose.[114] In 2009, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported that 83 of the 100 largest U.S. publicly traded corporations and 63 of the 100 largest contractors for the U.S. federal government were maintaining subsidiaries in countries generally considered havens for avoiding taxes. The GAO did not review the companies' transactions to independently verify that the subsidiaries helped the companies reduce their tax burden, but said only that historically the purpose of such subsidiaries is to cut tax costs.[115]

James Henry, former chief economist at consultants McKinsey & Company, in his report for the Tax Justice Network gives an indication of the amount of money that is sheltered by wealthy individuals in tax havens. The report estimated conservatively that a fortune of $21 trillion is stashed away in off-shore accounts with $9.8 trillion alone by the top tier—less than 100,000 people—who each own financial assets of $30 million or more. The report's author indicated that this hidden money results in a "huge" lost tax revenue—a "black hole" in the economy—and many countries would become creditors instead of being debtors if the money of their tax evaders would be taxed.[107][108][109]

Lost tax revenue

The Tax Justice Network estimated in 2012 that global tax revenue lost to tax havens was circa $190 to $255 billion per year (assuming a 3% capital gains rate, a 30% capital gains tax rate, and $21 to $32 trillion hidden in tax havens.[116] The Zucman study uses different methodology, but also estimates $190 billion in lost revenue.[17]

The UN Economic Commission for Africa estimates that illegal financial flows cost the continent around $50 billion per year. The OECD estimates that two-thirds ($30 billion) occur from tax avoidance and evasion from non-African firms.[117] The avoidance of taxation by international corporations through legal and illegal methods stifles development in African countries. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be difficult to obtain if these losses persist.[118]

In 2016 a massive data leak known as the "Panama Papers" cast some doubt on the size of previous estimates of lost revenue.[119]

However, the tax policy director of the Chartered Institute of Taxation expressed skepticism over the accuracy of the figures.[120] If true, those sums would amount to approximately 5 to 8 times the total amount of currency presently in circulation in the world. Daniel J. Mitchell of the Cato Institute says that the report also assumes, when considering notional lost tax revenue, that 100% money deposited offshore is evading payment of tax.[121]

In October 2009, research commissioned from Deloitte for the Foot Review of British Offshore Financial Centres said that much less tax had been lost to tax havens than previously had been thought. The report indicated "We estimate the total UK corporation tax potentially lost to avoidance activities to be up to £2 billion per annum, although it could be much lower." An earlier report by the U.K. Trades Union Congress, concluded that tax avoidance by the 50 largest companies in the FTSE 100 was depriving the UK Treasury of approximately £11.8 billion.[122] The report also stressed that British Crown Dependencies make a "significant contribution to the liquidity of the UK market". In the second quarter of 2009, they provided net funds to banks in the UK totaling $323 billion (£195 billion), of which $218 billion came from Jersey, $74 billion from Guernsey and $40 billion from the Isle of Man.[122]

The Tax Justice Network reports that this system is "basically designed and operated" by a group of highly paid specialists from the world’s largest private banks (led by UBS, Credit Suisse, and Goldman Sachs), law offices, and accounting firms and tolerated by international organizations such as Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the OECD, and the G20. The amount of money hidden away has significantly increased since 2005, sharpening the divide between the super-rich and the rest of the world.[107][108][109]

Incentives for tax havens

Inflated GDP-per-capita

Tax havens, traditional and corporate, have high GDP-per-capita rankings, because the haven's national economic statistics are artificially inflated by the BEPS accounting flows that add to the haven's GDP (and even GNP), but are not taxable in the haven.[75][123] As the largest facilitators of BEPS flows, corporate-focused tax havens, in particular, make up most of the top 10-15 GDP-per-capita tables, excluding oil and gas nations (see table below). Research into tax havens suggest a high GDP-per-capita score, in the absence of material natural resources, as an important proxy indicator of a tax haven.[124] At the core of the FSF-IMF definition of an offshore financial centre is a country where the BEPS flows are out of proportion to the size of the indigenous economy. Apple's Q1 2015 "leprechaun economics" BEPS transaction in Ireland was a dramatic example, which caused Ireland to abandon its GDP and GNP metrics in February 2017, in favour of a new metric, modified gross national income, or GNI*.

This artificial inflation of GDP can attract excess foreign capital, who misprice their capital by using a Debt-to-GDP metric for the haven, thus producing phases of stronger economic growth.[22] However, the increased leverage leads to more severe credit cycles, particularly where the artificial nature of the GDP is exposed to foreign investors.[125] An example is the Irish financial crisis in 2009–2013.[23]

| International Monetary Fund (2017) GDP-per-capita[126] | World Bank (2016) GDP-per-capita[126][127] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- Data is sourced from List of countries by GDP (PPP) per capita and the figures, where shown (marked by, ‡), are USD per capita for places that are not tax havens.

- "Top 10 Tax Haven" in the table refers to the § Top 10 tax havens above; 6 of the 9 tax havens that appear in all § Top 10 tax havens are represented above (Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Hong Kong), and the remaining 3 havens (Cayman Islands, Bermuda, British Virgin Islands), do not appear in World Bank-IMF GDP-per-capita tables.

- "Conduit OFC" and "Sink OFC" refers to University of Amsterdam's CORPNET's 2017 Conduit and Sink OFCs study

Importance of governance

In several research papers, James R. Hines Jr. showed that tax havens were typically small but well-governed nations and that being a tax haven had brought significant prosperity.[21][22] In 2009, Hines and Dharmapala suggested that roughly 15% of countries are tax havens, but they wondered why more countries had not become tax havens given the observable economic prosperity it could bring.[4]

There are roughly 40 major tax havens in the world today, but the sizable apparent economic returns to becoming a tax haven raise the question of why there are not more.

Hines and Dharmapala concluded that governance was a major issue for smaller countries in trying to become tax havens. Only countries with strong governance and legislation which was trusted by foreign corporates and investors, would become tax havens.[4] Hines and Dharmapala's positive view on the financial benefits of becoming a tax haven, as well as being two of the major academic leaders into tax haven research, put them in sharp conflict with non-governmental organisations advocating tax justice, such as the Tax Justice Network, who accused them as promoting tax avoidance.[128][129][130]

Benefits of tax havens

U.S. as the largest beneficiary

An unexpected conclusion of the original 1994 Hines-Rice paper, and re-affirmed by others,[131] was that: low foreign tax rates [from tax havens] ultimately enhance U.S. tax collections.[38] Hines noted that as a result of paying no foreign taxes by using tax havens, U.S. multinationals had avoided building up foreign tax credits that would reduce their ultimate U.S. tax liability. Hines returned to this finding several times, and in his 2010 § Important papers on tax havens, Treasure Islands, where he showed how U.S. multinationals used tax havens and BEPS tools to avoid Japanese taxes on their Japanese investments, noted that this was being confirmed by other empirical research at a company-level.[25] Hines's observations would influence U.S. policy towards tax havens, including the 1996 "check-the-box"[lower-alpha 7] rules, and U.S. hostility to OECD attempts in curbing Ireland's BEPS tools,[lower-alpha 8][26] and why, in spite of public disclosure of tax avoidance by firms such as Google, Facebook, and Apple, with Irish BEPS tools, little has been done by the U.S. to stop them.[131]

Lower foreign tax rates entail smaller credits for foreign taxes and greater ultimate U.S. tax collections (Hines and Rice, 1994).[38] Dyreng and Lindsey (2009),[25] offer evidence that U.S. firms with foreign affiliates in certain tax havens pay lower pay lower foreign taxes and higher U.S. taxes than do otherwise-similar large U.S. companies.

Research in June-September 2018, confirmed U.S. multinationals as the largest global users of tax havens and BEPS tools.[132][133]

U.S. multinationals use tax havens[lower-alpha 9] more than multinationals from other countries which have kept their controlled foreign corporations regulations. No other non-haven OECD country records as high a share of foreign profits booked in tax havens as the United States. [...] This suggests that half of all the global profits shifted to tax havens are shifted by U.S. multinationals. By contrast, about 25% accrues to E.U. countries, 10% to the rest of the OECD, and 15% to developing countries (Tørsløv et al., 2018).

— Gabriel Zucman, Thomas Wright, "THE EXORBITANT TAX PRIVILEGE", NBER Working Papers (September 2018).[73][74]

Tax justice groups interpreted Hines' research as the U.S. engaging in tax competition with higher-tax nations (i.e. the U.S. exchequer earning excess taxes at the expense of others). The 2017 TCJA seems to support this view with the U.S. exchequer being able to levy a 15.5% repatriation tax on over $1 trillion of untaxed offshore profits built up by U.S. multinationals with BEPS tools from non-U.S. revenues. Had these U.S. multinationals paid taxes on these non-U.S. profits in the countries in which they were earned, there would have been the little further liability to U.S. taxation. Research by Zucman and Wright (2018) estimated that most of the TCJA repatriation benefit went to the shareholders of U.S. multinationals, and not the U.S. exchequer.[73][lower-alpha 10]

Academics who study tax havens, attribute Washington's support of U.S. multinational use of tax havens to a "political compromise" between Washington, and even other higher-tax OECD nations, to compensate for the shortcomings of the U.S. "worldwide" tax system.[134][135] Hines had advocated for a switch to a "territorial" tax system, as most other nations use, which would remove U.S. multinational need for tax havens. In 2016, Hines, with German tax academics, showed that German multinationals make little use of tax havens because their tax regime, a "territorial" system, removes any need for it.[136]

Hines' research was cited by the by the Council of Economic Advisors ("CEA") in drafting the TCJA legislation in 2017, and advocating for moving to a hybrid "territorial" tax system framework.[137][138]

Promoters of global growth

A controversial area of research into tax havens is the suggestion that tax havens actually promote global economic growth by solving perceived issues in the tax regimes of higher-taxed nations (e.g. the above discussion on the U.S. "worldwide" tax system as an example). Important academic leaders in tax haven research, such as Hines,[140] Dharmapala,[34] and others,[131] cite evidence that, in certain cases, tax havens appear to promote economic growth in higher-tax countries, and can support beneficial hybrid tax regimes of higher taxes on domestic activity, but lower taxes on international sourced capital or income:

The effect of tax havens on economic welfare in high tax countries is unclear, though the availability of tax havens appears to stimulate economic activity in nearby high-tax countries.

Tax havens change the nature of tax competition among other countries, very possibly permitting them to sustain high domestic tax rates that are effectively mitigated for mobile international investors whose transactions are routed through tax havens. [..] In fact, countries that lie close to tax havens have exhibited more rapid real income growth than have those further away, possibly in part as a result of financial flows and their market effects.

The most cited paper on research into offshore financial centres ("OFCs"),[141] a closely related term to tax havens, noted the positive and negative aspects of OFCs on neighbouring high-tax, or source, economies, and marginally came out in favour of OFCs.[142]

CONCLUSION: Using both bilateral and multilateral samples, we find empirically that successful offshore financial centers encourage bad behavior in source countries since they facilitate tax evasion and money laundering [...] Nevertheless, offshore financial centers created to facilitate undesirable activities can still have unintended positive consequences. [...] We tentatively conclude that OFCs are better characterized as "symbionts".

— Andrew K. Rose, Mark M. Spiegel, "Offshore Financial Centers: Parasites or Symbionts?", The Economic Journal, (September 2007)[142]

However, other notable tax academics strongly dispute these views, such as work by Slemrod and Wilson, who in their § Important papers on tax havens, label tax havens as parasitic to jurisdictions with normal tax regimes, that can damage their economies.[139] In addition, tax justice campaign groups have been equally critical of Hines, and others, in these views.[129][130] Research in June 2018 by the IMF showed that much of the foreign direct investment ("FDI") that came from tax havens into higher-tax countries, had really originated from the higher-tax country,[75] and for example, that the largest source of FDI into the United Kingdom, was actually from the United Kingdom, but invested via tax havens.[143]

The boundaries with wider contested economic theories on the effects of corporate taxation on economic growth, and whether there should be corporate taxes, are easy to blur. Other major academic leaders in tax haven research, such as Zucman, highlight the injustice of tax havens and see the effects as lost income for the development of society.[144] It remains a controversial area with advocates on both sides.[145]

Methodology

The way tax havens operate can be viewed in the following principal contexts:[146]

Personal residency

Since the early 20th century, wealthy individuals from high-tax countries have sought to relocate themselves in low-tax countries. In most countries in the world, residence is the primary basis of taxation—see tax residence. The low-tax country chosen may levy no, or only very low, income tax and may not levy capital gains tax, or inheritance tax. Individuals are normally unable to return to their previous higher-tax country for more than a few days a year without reverting their tax residence to their former country. They are sometimes referred to as tax exiles.[146]

Corporate residency

Corporations can establish subsidiary corporations and/or regional headquarters in corporate tax havens for tax planning purposes. Where a corporate moves their legal headquarters to a haven, it is known as a corporate tax inversion.[69][147] The rise of intellectual property, or IP, as a major BEPS tax tool, has meant that corporates can achieve much of the benefits of a tax inversion, without needing to move their headquarters. Apple's $300 billion quasi-inversion to Ireland in 2015 (see leprechaun economics) is a good example of this.

Asset holding

Asset holding involves utilizing an offshore trust or offshore company, or a trust owning a company. The company or trust will be formed in one tax haven, and will usually be administered and resident in another. The function is to hold assets, which may consist of a portfolio of investments under management, trading companies or groups, physical assets such as real estate or valuable chattels. The essence of such arrangements is that by changing the ownership of the assets into an entity which is not tax resident in the high-tax country, they cease to be taxable in that country.[146]

Often the mechanism is employed to avoid a specific tax. For example, a wealthy testator could transfer his house into an offshore company; he can then settle the shares of the company on trust (with himself being a trustee with another trustee, whilst holding the beneficial life estate) for himself for life, and then to his daughter. On his death, the shares will automatically vest in the daughter, who thereby acquires the house, without the house having to go through probate and being assessed with inheritance tax.[148] Most countries assess inheritance tax, and all other taxes, on real estate within their jurisdiction, regardless of the nationality of the owner, so this would not work with a house in most countries. It is more likely to be done with intangible assets.[146]

Trading and other business activity

Many businesses which do not require a specific geographical location or extensive labor are set up in a country to minimize tax exposure. Perhaps the best illustration of this is the number of reinsurance companies which have migrated to Bermuda over the years. Other examples include internet-based services and group finance companies. In the 1970s and 1980s corporate groups were known to form offshore entities for the purposes of "reinvoicing". These reinvoicing companies simply made a margin without performing any economic function, but as the margin arose in a tax-free country, it allowed the group to "skim" profits from the high-tax country. Most sophisticated tax codes now prevent transfer pricing schemes of this nature.[146]

Financial intermediaries

Much of the economic activity in tax havens today consists of professional financial services such as mutual funds, banking, life insurance and pensions. Generally, the funds are deposited with the intermediary in the low-tax country, and the intermediary then on-lends or invests the money in another location. Although such systems do not normally avoid tax in the principal customer's country, it enables financial service providers to provide international products without adding another layer of taxation. This has proved particularly successful in the area of offshore funds. It has been estimated over 75% of the world's hedge funds, probably the riskiest form of collective investment vehicle, are domiciled in the Cayman Islands, with nearly $1.1 trillion US Assets under management[149] although statistics in the hedge fund industry are notoriously speculative.

Anonymity and bearer shares

Bearer shares allow for anonymous ownership, and thus have been criticized for facilitating money laundering and tax evasion; these shares are also available in some OECD countries as well as in the U.S. state of Wyoming.[150]:7 In a 2010 study in which the researcher attempted to set-up anonymous corporations found that 13 of the 17 attempts were successful in OECD countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, while only 4 of 28 attempts were successful in countries typically labeled tax havens.[151] The last two states in America permitting bearer shares, Nevada and Delaware made them illegal in 2007. In 2011, an OECD peer review recommended that the United Kingdom improve its bearer share laws.[152] The UK abolished the use of bearer shares in 2015.

In 2012 the Guardian wrote that there are 28 persons as directors for 21,500 companies.[153][154]

Money and exchange control

Most tax havens have a double monetary control system, which distinguish residents from non-resident as well as foreign currency from the domestic, the local currency one. In general, residents are subject to monetary controls, but not non-residents. A company, belonging to a non-resident, when trading overseas is seen as non-resident in terms of exchange control. It is possible for a foreigner to create a company in a tax haven to trade internationally; the company’s operations will not be subject to exchange controls as long as it uses foreign currency to trade outside the tax haven. Tax havens usually have currency easily convertible or linked to an easily convertible currency. Most are convertible to US dollars, euro or to pounds sterling.

Various developments

U.S. Legislation

The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) was passed by the US Congress to stop the outflow of money from the country into tax haven bank accounts. With the strong backing of the Obama Administration, Congress drafted the FATCA legislation and added it into the Hiring Incentives to Restore Employment Act (HIRE) signed into law by President Obama in March 2010.

FATCA requires foreign financial institutions (FFI) of broad scope – banks, stock brokers, hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies, trusts – to report directly to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) all clients who are U.S. persons. Starting January 2014, FATCA requires FFIs to provide annual reports to the IRS on the name and address of each U.S. client, as well as the largest account balance in the year and total debits and credits of any account owned by a U.S. person.[155] If an institution does not comply, the U.S. will impose a 30% withholding tax on all its transactions concerning U.S. securities, including the proceeds of sale of securities.

In addition, FATCA requires any foreign company not listed on a stock exchange or any foreign partnership which has 10% U.S. ownership to report to the IRS the names and tax identification number (TIN) of any U.S. owner. FATCA also requires U.S. citizens and green card holders who have foreign financial assets in excess of $50,000 to complete a new Form 8938 to be filed with the 1040 tax return, starting with fiscal year 2010.[156] The delay is indicative of a controversy over the feasibility of implementing the legislation as evidenced in this paper from the Peterson Institute for International Economics.[157]

An unintended consequence of FATCA and its cost of compliance for non-US banks is that some non-US banks are refusing to serve American investors.[158] Concerns have also been expressed that, because FATCA operates by imposing withholding taxes on U.S. investments, this will drive foreign financial institutions (particularly hedge funds) away from investing in the U.S. and thereby reduce liquidity and capital inflows into the US.[159]

Tax Justice Network Report 2012

A 2012 report by the British Tax Justice Network estimated that between US$21 trillion and $32 trillion is sheltered from taxes in unreported tax havens worldwide.[160] If such wealth earns 3% annually and such capital gains were taxed at 30%, it would generate between $190 billion and $280 billion in tax revenues, more than any other tax shelter.[116] If such hidden offshore assets are considered, many countries with governments nominally in debt are shown to be net creditor nations.[161] However, despite being widely quoted, the methodology used in the calculations has been questioned,[110] and the tax policy director of the Chartered Institute of Taxation also expressed skepticism over the accuracy of the figures.[120] Another recent study estimated the amount of global offshore wealth at the smaller—but still sizable—figure of US$7.6 trillion. This estimate included financial assets only: "My method probably delivers a lower bound, in part because it only captures financial wealth and disregards real assets. After all, high-net-worth individuals can stash works of art, jewelry, and gold in 'freeports,' warehouses that serve as repositories for valuables—Geneva, Luxembourg, and Singapore all have them. High-net-worth individuals also own real estate in foreign countries."[17] A study of 60 large US companies found that they deposited $166 billion in offshore accounts during 2012, sheltering over 40% of their profits from U.S. taxes.[113]

Bank data leak 2013

Details of thousands of owners of offshore companies were published in April 2013 in a joint collaboration between The Guardian and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.[162] The data was later published on a publicly accessible website in an attempt to "crowd-source" the data.[163] The publication of the list appeared to be timed to coincide with the 2013 G8 summit chaired by British Prime Minister David Cameron which emphasised tax evasion and transparency.

Liechtenstein banking scandal

Germany announced in February 2008 that it had paid €4.2 million to Heinrich Kieber,[164] a former data archivist of LGT Treuhand, a Liechtenstein bank, for a list of 1,250 customers of the bank and their accounts' details. Investigations and arrests followed relating to charges of illegal tax evasion. The German authorities shared the data with U.S. tax authorities, but the British government paid a further £100,000 for the same data.[165] Other governments, notably Denmark and Sweden, refused to pay for the information regarding it as stolen property.[166] The Liechtenstein authorities subsequently accused the German authorities of espionage.[167]

However, regardless of whether unlawful tax evasion was being engaged in, the incident has fuelled the perception among European governments and the press that tax havens provide facilities shrouded in secrecy designed to facilitate unlawful tax evasion, rather than legitimate tax planning and legal tax mitigation schemes. This in turn has led to a call for "crackdowns" on tax havens.[168] Whether the calls for such a crackdown are mere posturing or lead to more definitive activity by mainstream economies to restrict access to tax havens is yet to be seen. No definitive announcements or proposals have yet been made by the European Union or governments of the member states.

German legislation

Peer Steinbrück, the former German finance minister, announced in January 2009 a plan to amend fiscal laws. New regulations would disallow that payments to companies in certain countries that shield money from disclosure rules to be declared as operational expenses. The effect of this would make banking in such states unattractive and expensive.[169]

UK Foot report

In November 2009, Sir Michael Foot, a former Bank of England official and Bahamas bank inspector, delivered a report on the British Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories for HM Treasury.[170] The report indicated that while many of the territories "had a good story to tell", others needed to improve their abilities to detect and prevent financial crime. The report also stressed the view that narrow tax bases presented long term strategic risks and that the economies should seek to diversify and broaden their tax bases.[171]

It indicated that tax revenue lost by the UK government appeared to be much smaller than had previously been estimated (see above under Lost tax revenue), and also stressed the importance of the liquidity provided by the territories to the United Kingdom. The Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories broadly welcomed the report.[171] The pressure group Tax Justice Network, unhappy with the findings, commented that "[a] weak man, born to be an apologist, has delivered a weak report."[172]

G20 tax haven blacklist

At the London G20 summit on 2 April 2009, G20 countries agreed to define a blacklist for tax havens, to be segmented according to a four-tier system, based on compliance with an "internationally agreed tax standard."[173] The list as per 2 April 2009 can be viewed on the OECD website.[174] The four tiers were:

- Those that have substantially implemented the standard (includes most countries but China still excludes Hong Kong and Macau).

- Tax havens that have committed to – but not yet fully implemented – the standard (includes Montserrat, Nauru, Niue, Panama, and Vanuatu)

- Financial centres that have committed to – but not yet fully implemented – the standard (includes Guatemala, Costa Rica and Uruguay).

- Those that have not committed to the standard (an empty category)

Those countries in the bottom tier were initially classified as being 'non-cooperative tax havens'. Uruguay was initially classified as being uncooperative. However, upon appeal the OECD stated that it did meet tax transparency rules and thus moved it up. The Philippines took steps to remove itself from the blacklist and Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak had suggested earlier that Malaysia should not be in the bottom tier.[175]

In April 2009 the OECD announced through its chief Angel Gurria that Costa Rica, Malaysia, the Philippines and Uruguay have been removed from the blacklist after they had made "a full commitment to exchange information to the OECD standards."[176] Despite calls from the former French President Nicolas Sarkozy for Hong Kong and Macau to be included on the list separately from China, they are as yet not included independently, although it is expected that they will be added at a later date.[173]

Government response to the crackdown has been broadly supportive, although not universal.[177] Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker has criticised the list, stating that it has "no credibility", for failing to include various states of the USA which provide incorporation infrastructure which are indistinguishable from the aspects of pure tax havens to which the G20 object.[178] As of 2012, 89 countries have implemented reforms sufficient to be listed on the OECD's white list.[179] According to Transparency International half of the least corrupted countries were tax havens.[180]

EU tax haven blacklist

In December 2017, European Union adopted blacklist of tax havens in a bid to discourage the most aggressive tax dodging practices. It also had a so-called gray list which includes those who have committed to change their rules on tax transparency and cooperation. The 17 blacklisted territories are: American Samoa, Bahrain, Barbados, Grenada, Guam, South Korea, Macau, The Marshall Islands, Mongolia, Namibia, Palau, Panama, Saint Lucia, Samoa, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates.[181] Some activists denounced the listing process as a whitewash and had called for the inclusion in the blacklist of some EU countries accused of facilitating tax avoidance, like Luxembourg, Malta, Ireland and the Netherlands.[182]

Common Reporting Standard (CRS)

The Common Reporting Standard is an information standard for the automatic exchange of tax and financial information on a global level developed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2014. Participating in the CRS from 1 January 2017 onwards are Australia, the Bahamas, Bahrain, Brazil, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, China, The Cook Islands, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Israel, Japan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Macau, Malaysia, Mauritius, Monaco, New Zealand, Panama, Qatar, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Uruguay.[183]

History

The use of differing tax laws between two or more countries to try to mitigate tax liability is probably as old as taxation itself.[48]In Ancient Greece, some of the Greek Islands were used as depositories by the sea traders of the era to place their foreign goods to thus avoid the two-percent tax imposed by the city-state of Athens on imported goods. The practice may have first reached prominence through the avoidance of the Cinque Ports and later the staple ports in the twelfth and fourteenth centuries respectively. In 1721, American colonies traded from Latin America to avoid British taxes.

Various countries claim to be the oldest tax haven in the world. For example, the Channel Islands claim their tax independence dating as far back as Norman Conquest, while the Isle of Man claims to trace its fiscal independence to even earlier times. Nonetheless, the modern concept of a tax haven is generally accepted to have emerged at an uncertain point in the immediate aftermath of World War I.[184] Bermuda sometimes optimistically claims to have been the first tax haven based upon the creation of the first offshore companies legislation in 1935 by the newly created law firm of Conyers Dill & Pearman.[185] However, the Bermudian claim is debatable when compared against the enactment of a Trust Law by Liechtenstein in 1926 to attract offshore capital.[186]

Most economic commentators suggest that the first "true" tax haven was Switzerland, followed closely by Liechtenstein.[146] Swiss banks had long been a capital haven for people fleeing social upheaval in Russia, Germany, South America and elsewhere. However, in the early part of the twentieth century, during the years immediately following World War I, many European governments raised taxes sharply to help pay for reconstruction efforts following the devastation of World War I. By and large, Switzerland, having remained neutral during the Great War, avoided these additional infrastructure costs and was consequently able to maintain a low level of taxes. As a result, there was a considerable influx of capital into the country for tax related reasons. It is difficult, nonetheless, to pinpoint a single event or precise date which clearly identifies the emergence of the modern tax haven.

The use of modern tax havens has gone through several phases of development subsequent to the interwar period. From the 1920s to the 1950s, tax havens were usually referenced as the avoidance of personal taxation. The terminology was often used with reference to countries to which a person could retire and mitigate their post retirement tax position, a usage which was still being echoed to some degree in a 1990 report, which included indications of quality of life in various tax havens which future tax exiles may wish to consider.[187]

From the 1950s onward, there was significant growth in the use of tax havens by corporate groups to mitigate their global tax burden. The strategy generally relied upon there being a double taxation treaty between a large country with a high tax burden (that the company would otherwise be subject to), and a smaller country with a low tax burden. By structuring the group ownership through the smaller country, corporations could take advantage of the double taxation treaty, paying taxes at the much lower rate. Although some of these double tax treaties survive,, for example between Barbados and Japan, between Cyprus and Russia and Mauritius with India, which India sought to renegotiate in 2007,[188] most major countries began repealing their double taxation treaties with micro-states in the 1970s, to prevent corporate tax leakage in this manner.

In the early to mid-1980s, most tax havens changed the focus of their legislation to create corporate vehicles which were "ring-fenced" and exempt from local taxation (although they usually could not trade locally either). These vehicles were usually called "exempt companies" or "international business corporations". However, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the OECD began a series of initiatives aimed at tax havens to curb the abuse of what the OECD referred to as "unfair tax competition". Under pressure from the OECD, most major tax havens repealed their laws permitting these ring-fenced vehicles to be incorporated, but concurrently they amended their tax laws so that a company which did not actually trade within the country would not accrue any local tax liability.[189]

Important papers on tax havens

The following are the most cited papers on "tax havens", as ranked on the IDEAS/RePEc database of economic papers, at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.[28]

Papers marked (‡) were cited by the EU Commission 2017 summary as the most important research on tax havens.[37]

| Rank | Paper | Journal | Vol-Issue-Page | Author(s) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‡ | Fiscal Paradise: Foreign tax havens and American Business[38] | The Quarterly Journal of Economics | 109 (1) 149-182 | James R. Hines Jr., Eric Rice | 1994 |

| 2‡ | The demand for tax haven operations[114] | Journal of Public Economics | 90 (3) 513-531 | Mihir A. Desai, C Fritz Foley, James R. Hines Jr. | 2006 |

| 3‡ | Which countries become tax havens?[4] | Journal of Public Economics | 93 (9-10) 1058-1068 | Dhammika Dharmapala, James R. Hines Jr. | 2009 |

| 4‡ | The Missing Wealth of Nations: Are Europe and the U.S. net Debtors or net Creditors?[10] | The Quarterly Journal of Economics | 128 (3) 1321-1364 | Gabriel Zucman | 2013 |

| 5‡ | Tax competition with parasitic tax havens[139] | Journal of Public Economics | 93 (11-12) 1261-1270 | Joel Slemrod, John D. Wilson | 2006 |

| 6 | What problems and opportunities are created by tax havens?[34] | Oxford Review of Economic Policy | 24 (4) 661-679 | Dhammika Dharmapala, James R. Hines Jr. | 2008 |

| 7 | In praise of tax havens: International tax planning[131] | European Economic Review | 54 (1) 82-95 | Qing Hong, Michael Smart | 2010 |

| 8‡ | End of bank secrecy: An Evaluation of the G20 tax haven crackdown | American Economic Journal | 6 (1) 65-91 | Niels Johannesen, Gabriel Zucman | 2014 |

| 9‡ | Taxing across borders: Tracking wealth and corporate profits[17] | Journal of Economic Perspectives | 28 (4) 121-148 | Gabriel Zucman | 2014 |

| 10‡ | Treasure Islands[20] | Journal of Economic Perspectives | 24 (4) 103-26 | James R. Hines Jr. | 2010 |

See also

- Asset protection

- Association for the Taxation of Financial Transactions and for Citizens' Action

- Bank secrecy

- Conduit and Sink OFCs

- Corporate haven

- Corporate inversion

- Flag of convenience

- Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act

- Free port

- Free economic zone

- Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes

- International business company

- International taxation

- Ireland as a tax haven

- List of foundations established in Vaduz

- List of countries by tax rates

- Luxembourg leaks

- Offshore bank

- Offshore company

- Offshore financial centre

- Offshore trust

- Panama as a tax haven

- Panama Papers

- Paradise Papers

- Pirate haven

- Tax noncompliance

- Tax exile

- Tax exporting

- Tax Justice Network

- Tax shelter

- United States as a tax haven

- Vulture fund

Notes

- ↑ Many corporate-focused tax havens have high nominal rates of taxation (e.g. Netherlands at 25%, United Kingdom at 19%, Singapore at 17%, and Ireland at 12.5%), but maintain a tax regime that excludes sufficient items from taxable income to bring the effective rates of taxation closer to zero

- ↑ Since the post-2000 OECD-IMF-FATF initiatives on reducing banking secrecy and increasing transparency, modern academics consider the secrecy component to be redundant. See § Definitions.

- 1 2 3 The FSI is often misquoted as a ranking of "tax havens", however the FSI does not quantify tax avoidance or BEPS flows like modern quantitative tax haven lists; the FSI it is a qualitative scoring of secrecy indicators, and does not score some of the most common secrecy tools - the unlimited liability company, the trust, and various special purpose vehicles (e.g. Irish QIAIFs and L-QIAIFs) - few of which are required to file public accounts in major tax havens, such as Ireland and the United Kingdom.[7][8]

- ↑ The list of sovereign states numbered 206 as at September 2018, so 15% equates to just over 30 tax havens; the OECD's 2000 list had 35 tax havens,[19] the James Hines 2010 list had 52 tax havens[20], the 2017 Conduit and Sink OFCs study lists 29 states.

- ↑ The final report by tbe Council of Economic Advisors on the economic theory underpinning the TCJA, also used other tax papers from Hines, and also referenced Mihir A. Deasi and Dhammika Dharmapala's work, two of Hines' co-authors in tax haven research

- 1 2 The ITEP list only focuses on Fortune 500 Companies; its strong correlation with tax haven lists derived from global studies highlights that U.S multinationals are the most dominant source of global tax avoidance, and users of tax havens.

- ↑ Before 1996, the United States, like other high-income countries, had anti-avoidance rules—known as “controlled foreign corporations” provisions—designed to immediately tax in the United States some foreign income (such as royalties and interest) conducive of profit shifting. In 1996, the IRS issued regulations that enabled U.S. multinationals to avoid some of these rules by electing to treat their foreign subsidiaries as if they were not corporations but disregarded entities for tax purposes. This move is called “checking the box” because that is all that needs to be done on IRS form 8832 to make it work and use Irish BEPS tools on non-U.S. revenues was a compromise to keep U.S. multinationals from leaving the U.S. (page 10.)[73]

- ↑ The U.S. refused to sign the OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument ("MLI") on the 24 November 2016.

- ↑ The paper lists tax havens as: Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda and Caribbean havens (page 6.)

- ↑ Zucman and Wright's analysis assumed that U.S. multinationals were going to pay a U.S. 35% rate eventually (e.g. they would repatriate their untaxed offshore cash at some stage in the future); if the assumption is made that they were going to permanently leave their offshore cash outside of the U.S., then the U.S. exchequer was the main beneficiary

References

- 1 2 "Financial Times Lexicon: Definition of tax haven:". Financial Times. June 2018.

A country with little or no taxation that offers foreign individuals or corporations residency so that they can avoid tax at home.

- 1 2 "Tax haven definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". Collins Dictionary. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

A tax haven is a country or place which has a low rate of tax so that people choose to live there or register companies there in order to avoid paying higher tax in their own countries.

- 1 2 "Tax haven definition and meaning | Cambridge English Dictionary". Cambridge English Dictionary. 2018.

a place where people pay less tax than they would pay if they lived in their own country

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Dhammika Dharmapala; James R. Hines Jr. (2009). "Which countries become tax havens?" (PDF). Journal of Public Economics. 93 (9–10): 1058-1068.

The “tax havens” are locations with very low tax rates and other tax attributes designed to appeal to foreign investors.

- 1 2 James R. Hines Jr.; Anna Gumpert; Monika Schnitzer (2016). "Multinational Firms and Tax Havens". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 98 (4): 713-727.

Tax havens are typically small, well-governed states that impose low or zero tax rates on foreign investors.

- ↑ Shaxson, Nicholas (9 January 2011). "Explainer: what is a tax haven?". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2017.

- ↑ "New report: is Apple paying less than 1% tax in the EU?". Tax Justice Network. 28 June 2018.

The use of private "unlimited liability company" (ULC) status, which exempts companies from filing financial reports publicly. The fact that Apple, Google and many others continue to keep their Irish financial information secret is due to a failure by the Irish government to implement the 2013 EU Accounting Directive, which would require full public financial statements, until 2017, and even then retaining an exemption from financial reporting for certain holding companies until 2022

- ↑ "Ireland's playing games in the last chance saloon of tax justice". Richard Murphy. 4 July 2018.

Local subsidiaries of multinationals must always be required to file their accounts on public record, which is not the case at present. Ireland is not just a tax haven at present, it is also a corporate secrecy jurisdiction.

- 1 2 3 4 Laurens Booijink; Francis Weyzig (July 2007). "IDENTIFYING TAX HAVENS AND OFFSHORE FINANCE CENTRES" (PDF). Tax Justice Network and Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations.

Various attempts have been made to identify and list tax havens and offshore finance centres (OFCs). This Briefing Paper aims to compare these lists and clarify the criteria used in preparing them.

- 1 2 3 4 Gabriel Zucman (August 2013). "THE MISSING WEALTH OF NATIONS: ARE EUROPE AND THE U.S. NET DEBTORS OR NET CREDITORS?" (PDF). The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 128 (3): 1321-1364.

Tax havens are low-tax jurisdictions that offer businesses and individuals opportunities for tax avoidance” (Hines, 2008). In this paper, I will use the expression “tax haven” and “offshore financial center” interchangeably (the list of tax havens considered by Dharmapala and Hines (2009) is identical to the list of offshore financial centers considered by the Financial Stability Forum (IMF, 2000), barring minor exceptions)

- 1 2 "Netherlands and UK are biggest channels for corporate tax avoidance". The Guardian. 25 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Is the U.K. Already the Kind of Tax Haven It Claims It Won't Be?". Bloomberg News. 31 July 2017.

- ↑ "Tax Havens Can Be Surprisingly Close to Home". Bloomberg View. 11 April 2017.

- ↑ "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018.

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $250 billion globally

- 1 2 "The Missing Profits of Nations" (PDF). Gabriel Zucman (University of Berkley). April 2018. p. 68.

- 1 2 "BEPS Project Background Brief" (PDF). OECD. January 2017. p. 9.

With a conservatively estimated annual revenue loss of USD 100 to 240 billion, the stakes are high for governments around the world. The impact of BEPS on developing countries, as a percentage of tax revenues, is estimated to be even higher than in developed countries.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gabriel Zucman (August 2014). "Taxing across Borders: Tracking Personal Wealth and Corporate Profits". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 28 (4): 121–48. doi:10.1257/jep.28.4.121. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- 1 2 "The desperate inequality behind global tax dodging". The Guardian. 8 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Towards Global Tax Co-operation" (PDF). OECD. April 2000. p. 17.

TAX HAVENS: 1.Andorra 2.Anguilla 3.Antigua and Barbuda 4.Aruba 5.Bahamas 6.Bahrain 7.Barbados 8.Belize 9.British Virgin Islands 10.Cook Islands 11.Dominica 12.Gibraltar 13.Grenada 14.Guernsey 15.Isle of Man 16.Jersey 17.Liberia 18.Liechtenstein 19.Maldives 20.Marshall Islands 21.Monaco 22.Montserrat 23.Nauru 24.Net Antilles 25.Niue 26.Panama 27.Samoa 28.Seychelles 29.St. Lucia 30.St. Kitts & Nevis 31.St. Vincent and the Grenadines 32.Tonga 33.Turks & Caicos 34.U.S. Virgin Islands 35.Vanuatu

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 James R. Hines Jr. (2010). "Treasure Islands". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (24): 103-125.

Table 1: 52 Tax Havens

- 1 2 3 James R. Hines Jr. (2007). "Tax Havens" (PDF). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics.

Tax havens are low-tax jurisdictions that offer businesses and individuals opportunities for tax avoidance. They attract disproportionate shares of world foreign direct investment, and, largely as a consequence, their economies have grown much more rapidly than the world as a whole over the past 25 years.