Leprechaun economics

Leprechaun economics is the term used by Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman to describe the 26.3 per cent increase in Irish 2015 GDP, that was later revised to 34.4 per cent,[lower-alpha 1] in a 12 July 2016 publication by the Irish Central Statistics Office ("CSO") restating 2015 Irish national accounts.[1]

Leprechaun economics: Ireland reports 26 percent growth! But it doesn't make sense. Why are these in GDP?

.png)

While the event which caused the artificial Irish GDP growth occurred in Q1 2015, the Irish CSO had to delay the Irish 2015 GDP revision, and redact the release of its regular economic data in 2016-2017, to protect the source's identity.[4] Only in Q1 2018, could economists confirm Apple as the source,[5] and that "leprechaun economics" was the largest individual base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") action, and the largest quasi-tax inversion of a U.S. corporation, in history.[3]

"Leprechaun economics" marked the first known replacement of Ireland's prohibited BEPS tool, the double Irish, with the more powerful Irish BEPS tool, the "capital allowances for intangible assets" ("CAIA") tool, also called the "Green Jersey". Apple used the "Green Jersey" to restructure out of its hybrid double Irish BEPS tool, on which the EU Commission would levy a €13 billion fine in August 2016 for illegal avoidance of Irish taxes over the 2004-2014 period.[lower-alpha 2] Whereas Washington blocked the proposed USD 160 billion Pfizer-Allergan Irish tax inversion in April 2016, Apple executed a USD 300 billion tax inversion of its entire non-U.S. business to Ireland. Research in June 2018, using 2015 data, confirmed Ireland, already a "major tax haven", was now the world's largest tax haven.[7][8][9]

"Leprechaun economics" had material follow-on consequences:

- In September 2016, Ireland became the first of the "major tax havens", to be "blacklisted" by a G20 economy, Brazil.[10][11]

- In February 2017, the Ireland replaced GDP and GNP with a new metric, "Modified GNI" (GNI*), due to the distortions of BEPS tools.[12]

- In November 2017, the EU started new enquiries into Apple in Ireland,[13][14] which has led some to debate § Did Apple still pay tax?

- By December 2017, the U.S. and EU moved to introduce new anti-BEPS tool tax regimes (e.g. U.S. GILTi-BEAT-FDII regime, and EU DST).[15][16][17]

- By April 2018, economists noted EU-28 aggregate GDP was being distorted by Irish BEPS tools, and was affected by the iPhone sales cycle.[18][19][20]

- In June 2018, it was reported that Microsoft was preparing to execute a USD 100 billion "Green Jersey" BEPS transaction (e.g. one-third of Apple's).[21]

- By August 2018, the Central Statistics Office (Ireland)'s further restated 2015 Irish GDP data revised the 2015 GDP growth rate to 34.4 per cent;[lower-alpha 1] making leprechaun economics the highest post-war real annual GDP growth rate, of any OECD country.[22]

Post "leprechaun economics", Ireland's public "debt metrics" differ dramatically depending on whether Debt-to-GDP, Debt-to-GNI* or Debt-per-Capita is used.[23]

Adoption of term

On the 12 July 2016 at 11am GMT, the Central Statistics Office (Ireland) posted a data revision showing that 2015 Irish GDP data had risen by 26.3 per cent[lower-alpha 1] and 2015 Irish GNP had risen by 18.7 per cent.[1] Twenty four minutes later, at 11.24am GMT, Nobel-prize winning economist Paul Krugman responded to the data-release:

Leprechaun economics: Ireland reports 26 percent growth! But it doesn't make sense. Why are these in GDP?

Over the 12–13 July 2016, the term "leprechaun economics" was quoted widely by the Irish and international media when discussing Ireland's revised 26.3% 2015 GDP growth rate.[24][25][26][27][28][27][29][30] "Leprechaun economics" become a label for the Irish 2015 GDP 26.3% growth rate, and used by a diverse range of sources.[31]

Since July 2016, "leprechaun economics" has also been used many times (and by Krugman himself), to describe distorted/unsound economic data, including:

- Krugman in relation to the effects of the US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act[32]

- Krugman in relation to national statistics from some Eastern European Countries[33]

- Irish Times in relation to Irish house building completion statistics[34]

- Bloomberg in relation to US economic data and in particular, US trade deficit figures[35]

- U.S. Council on Foreign Relations in relation to the increasing distortion of EU-28 economic data (by Ireland).[18]

In addition, post July 2016, "leprechaun economics" has been also been used by economists in relation to caveats and concerns regarding Irish economic data.[36][37][38][39]

Nobody believes our GDP numbers any more, not after a 26 per cent jump in 2015, which was famously derided as "leprechaun economics". Even the CSO cautions against viewing last year's [2017] 7.8 per cent jump as a reflection of real economic activity

In March 2018, the first paper was published in an established international economic journal, the New Political Economy, with "leprechaun economics" in its title: "Celtic Phoenix or Leprechaun Economics? The Politics of an FDI-led Growth Model in Europe".[41] By September 2018, the term "leprechaun economics" had been used 83 times during debates in the Irish Dáil Éireann.[42]

Obfuscation of source

.jpg)

Despite the scale of the revision to 2015 Irish GDP,[43] the Irish Central Statistics Office ("CSO") issued a short one-page note on the 12 July 2016 explaining that it was as a result of an annual benchmarking exercise. The CSO also stated that: As a consequence of the overall scale of these additions, elements of the results that would previously been published are now suppressed to protect the confidentiality of the contributing companies, in accordance with the Statistics Act 1993.[4]

On the 12 July 2016, the Irish State attributed the 2015 growth revision to a combination of factors, including aircraft purchases (Ireland is a hub for aircraft securitisation), and the reclassification of technology and pharmaceutical corporate balance sheets following the closure of the double Irish tax scheme in 2014,[44][45] despite the fact that existing users of the double Irish, which Noonan was referring to, had until 2020 to switch out of their Irish BEPS tool.[46][47]

On the 13 July 2016, the ex-Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland made the following comment:

The statistical distortions created by the impact on the Irish National Accounts of the global assets and activities of a handful of large multinational corporations have now become so large as to make a mockery of conventional uses of Irish GDP.

The delay by the CSO in publishing revisions to Q1 2015 data (the period in which the growth appeared), as well as the redaction of regular CSO data from 2016-2017, meant that it would take almost three years for economists to show § Proof of Apple in Q1 2018. In addition, the CSO further obfuscated the picture by asserting that the "leprechaun economics" growth was not attributable to a main source, but was from several sources and part of Ireland's position as a Modernised Global Economy.[49]

By September 2016, economists speculated "leprechaun economics" was due to Apple restructuring Apple Sales International ("ASI"), which they knew was the focus of the EU Commission's 2004-2014 investigation into Apple's Irish base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") scheme, known as the double Irish.[50][51] While the double Irish is a widely used Irish BEPS tool, Apple's Irish subsidiary, ASI, used a hybrid version approved by the Irish Revenue, which the EU Commission argued was State aid. In September 2016, the Irish CSO again refuted this claim and repeated its assertion that the growth was from a range of sources including aircraft leasing.[52]

By early 2017, research in the Sloan School of Management in the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, using the limited data released by the Irish CSO, could conclude: While corporate inversions and aircraft leasing firms were credited for increasing Irish [2015] GDP, the impact may have been exaggeraged.[53]

The use by Ireland of complex data protection and data privacy laws, such as contained in the 1993 Statistics Act, to protect Irish BEPS tools and Irish corporate tax avoidance schemes is documented by tax justice groups (see captured state). The Irish Central Statistics Office was accused of "putting on the green jersey" to hide Apple's tax planning schemes, by some Irish political opposition groups.[54] The Central Statistics Office (Ireland) did not list Modified GNI (discussed later) in their Key Summary Economic Indicitors for September 2018, but only quote GDP, GNP and Debt-to-GDP.[55]

EU GDP levy

In July 2016, the Irish media reported that while the drivers of Ireland's "leprechaun economics" growth might not have produced tangible additional tax revenues for Ireland, the 26.3%[lower-alpha 1] rise in Ireland's GDP directly increased Ireland's annual EU budget levy, which is calculated as a percentage of Eurostat GDP, by an estimated €380 million per annum.[56][57]

In September 2016, the Irish Government appealed to the EU Commission to amend the terms of the EU GDP levy to a GNI approach, so Ireland would not incur the full €380 million increase. There were unsubstantiated claims by the Irish Government that the effective impact of the increase in the GDP levy would be reduced to circa €280 million per annum.[58]

The "leprechaun economics" affair prompted an October 2016 audit by Eurostat into Ireland's economic statistics, including questions from the International Monetary Fund, however no irregularities ensued and it was accepted that the Irish Central Statistics Office had followed the Eurostat guidelines, as detailed in the Eurostat ESA 2010 Guidelines manual, in preparing the 2015 National Accounts.[59][60]

On the 8 November 2016, a report by the EU Director-General for Internal Policies ("DG IPOL") on Ireland's "leprechaun economics" affair, noted that Detailed explanations are not provided, due to confidentiality rules aimed at protecting companies, and that the International Monetary Fund had stated that Additional metrics better reflecting the underlying developments of the Irish economy should be developed.[60] The report concluded that: It is becoming increasingly difficult to represent the complexity of economic activity in Ireland in a single headline indicator such as GDP.[60]

Proof of Apple

.png)

Economist Seamus Coffey is Chairman of the State's Irish Fiscal Advisory Council,[61] and authored the State's 2017 Review of Ireland's Corporation Tax Code.[62][63] Coffey had analysed Apple's Irish structure in detail,[64] and was interviewed by the international media on Apple in Ireland.[65] However, despite speculation,[50] the suppression of regular economic data by the Irish Central Statistics Office meant that no economist could confirm the source of "leprechaun economics" was Apple.

On 24 January 2018, Coffey published a long analysis on his respected economics blog, confirming the data now proved Apple was the source:[5]

We know Apple changed its structure from the first of January 2015. This is described in section 2.5.7 on page 42 of the EU Commission's decision [on Apple's State aid case].[6] This would be useful but bar telling us that the new structure came into operation on the first of January 2015 everything else is redacted. Although the details of the new structure were not revealed it was still felt that Ireland was still central to the structure and maybe even more so with the revised structure. Many of the dramatic shifts that occurred in Ireland's national accounts and balance of payments data were attributed to Apple but this was largely supposition – even if it was likely to be true. Now we know it to be true.

.png)

Coffey's January 2018 post also showed that Apple had restructured into the Irish capital allowances for intangible assets ("CAIA") BEPS tool. Apple's previous hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool had a modest effect on Irish economic data as it was offshore. However, by onshoring their intellectual property ("IP") from Jersey, via the CAIA BEPS tool, the full effect of circa USD 40 billion in profits that ASI was shifting by 2015 (see Table 1), would appear in the Irish national accounts.[5] This was equivalent to over 20% of Irish GDP. In April 2018, the IMF began to correlate Ireland's economic growth with the Apple iPhone sales cycle.[19][20]

| Year |

ASI Profit Shifted (USD m) |

Average €/$ rate |

ASI Profit Shifted (EUR m) |

Irish Corp. Tax Rate |

Irish Corp. Tax Avoided (EUR m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 268 | .805 | 216 | 12.5% | 27 |

| 2005 | 725 | .804 | 583 | 12.5% | 73 |

| 2006 | 1,180 | .797 | 940 | 12.5% | 117 |

| 2007 | 1,844 | .731 | 1,347 | 12.5% | 168 |

| 2008 | 3,127 | .683 | 2,136 | 12.5% | 267 |

| 2009 | 4,003 | .719 | 2,878 | 12.5% | 360 |

| 2010 | 12,095 | .755 | 9,128 | 12.5% | 1,141 |

| 2011 | 21,855 | .719 | 15,709 | 12.5% | 1,964 |

| 2012 | 35,877 | .778 | 27,915 | 12.5% | 3,489 |

| 2013 | 32,099 | .753 | 24,176 | 12.5% | 3,022 |

| 2014 | 34,229 | .754 | 25,793 | 12.5% | 3,224 |

| Total | 147,304 | 110,821 | 13,853 |

By April 2018, economists confirmed Coffey's analysis, and estimated Apple onshored USD 300 billion of IP from Jersey in Q1 2015 in the largest recorded BEPS action in history.[3][66] In June 2018, the GUE-NGL EU Parliament group published an analysis of Apple's new Irish CAIA BEPS tool, they labeled the "the Green Jersey".[67][68]

In July 2018, it was reported that Microsoft was preparing to execute a "Green Jersey" BEPS transaction.[21] which, due to technical issues with the TCJA, makes the CAIA BEPS tool attractive to U.S. multinationals. In July 2018, Coffey posted that Ireland could see a "boom" in the onshoring of U.S. IP between now and 2020.[69]

Further Apple controversy

The November 2017 Paradise Papers leaks, documented how in 2014 Apple and its lawyers, offshore magic circle firm Appleby, looked for a replacement for Apple's Irish hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool. The leaks show Apple considering a number of tax havens, especially Jersey and Ireland. Some of the disclosed documents demonstrate clearly that tax avoidance was the driver of Apple's decision making.[70][71][72]

It is prohibited in Ireland's tax code (Section 291A(c) of the Taxes and Consolation Act 1997), to use the CAIA BEPS tool for reasons that are not "commercial bona fide reasons", and in schemes where the main purpose is "... the avoidance of, or reduction in, liability to tax".[73][74][75] If the Irish Revenue waived its anti-avoidance measures under Section 291A(c) to Apple's benefit, it could be construed as further illegal EU State aid.

In November 2017, the Irish media noted that the then Finance Minister Michael Noonan, had increased the tax relief threshold for the Irish CAIA BEPS scheme from 80 per cent to 100 per cent in the 2015 budget, which would reduce the effective Irish corporate tax rate on the CAIA BEPS tool from 2.5 per cent to 0 per cent. This was changed back in the subsequent 2017 budget by the new Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe, however firms which had started their Irish CAIA BEPS tool in 2015, like Apple, were allowed to stay at the 100 per cent relief level for the duration of their scheme,[76][77] which can, under certain conditions, be extended indefinitely.[75]

In November 2017, it was reported that the EU Commission had asked for details on Apple's new Irish structure post the EU Commission's 2004-2014 ruling.[14]

In January 2018, when Seamus Coffey (and others) had § Proof of Apple as the source of "leprechaun economics", the above issues came into context. In a series of articles in January 2018, Coffey estimated that since the Q1 2015 restructuring, Apple avoided Irish corporate taxes of €2.5-3bn per annum, based on the 0% effective tax rate that Noonan had introduced for the CAIA scheme in the 2015 budget.[5][78] Coffey showed that a potential second EU Apple State aid fine for the 2015-2018 (inclusive) period, would therefore reach over €10bn, excluding any interest penalties,[13][79] adding to Apple's existing €13 billion EU fine for the 2004-2014 period.

Did Apple still pay tax?

In July 2016, it appeared that Ireland had incurred €380 million per annum in additional EU GDP levies and given Apple, in the 2015 budget (per above), a completely tax-free CAIA BEPS tool for the IP that was onshored in Q1 2015. Some commentators pointed to the benefits of "leprechaun economics" to Ireland's credit rating, and Debt-to-GDP metrics.[80]

However, in August 2016, Apple CEO Tim Cook, stated that Apple was now "the largest tax payer in Ireland".[81]

In April 2017, the Revenue Commissioners released Irish corporation tax data for 2015 showing a 49% increase, or €2.26 billion, to €6.87 billion in one year.[82] The report also showed that "intangible allowances", which are claimed under the CAIA BEPS tool, jumped by over 1,000 per cent, or €26.2 billion in 2015 (from €2.7 billion in 2014), which was consistent with the euro amount of profits that ASI was shifting through its hybrid-double Irish BEPS tool at the time.[5] However, the €2.26 billion jump in corporate tax revenue for 2015 also looked similar to the effective tax that ASI would pay in Ireland if it was not using any Irish BEPS tools. No other company has been identified as the source of such a large jump in Irish corporation tax in a single year, as it requires Irish profits of USD 30 billion.

Seamus Coffey has posted several articles in 2018 on the rise in Irish "intangible allowances", which hit €35.7 billion in 2016, or €4.5 billion of Irish corporate tax avoided at the 12.5% rate.[83] This is consistent 2018 research showing that the "Green Jersey" is the largest BEPS tool in the world. However, in the absence of confirming data, Coffey is reluctant to draw a parallel between the dramatic 2015 rise in Irish corporation tax receipts, which has carried into 2016, and any potential change of tax strategy by Apple from the additional EU scrutiny into Apple's Q1 2015 restructure.[84]

Introduction of GNI*

.png)

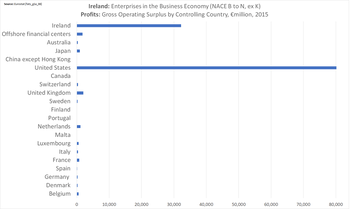

Since the first academic research into tax havens by James R. Hines Jr. in 1994, Ireland has been identified as a tax haven (one of Hines' seven major havens).[85] Hines would go on to become the most-cited author in the research of tax havens,[86] recording Ireland's rise to become the 3rd largest global tax haven in the Hines 2010 list.[87] As well as identifying and ranking tax havens, Hines, and others, including Dhammika Dharmapala, established that one of the main attributes of tax havens, is the artificial distortion of the haven's GDP from the BEPS accounting flows.[88] The highest GDP-per-capita countries, ex. oil & gas nations, are all tax havens.

In 2010, as part of Ireland's ECB bailout, Eurostat began tracking the distortion of Ireland's national accounts by BEPS flows. By 2011, Eurostat showed that Ireland's ratio of GNI to GDP, had fallen to 80% (i.e. Irish GDP was 125% of Irish GNI, or artificially inflated by 25%). Only Luxembourg, who ranked 1st on Hines' 2010 list of global tax havens,[87] was lower at 73% (i.e. Luxembourg GDP was 137% of Luxembourg GNI). Eurostat's GNI/GDP table (see graphic) showed EU GDP is equal to EU GNI for almost every EU country, and for the aggregate EU-27 average.[89][90] A 2015 Eurostat report showed that from 2010 to 2015, almost 23% of Ireland's GDP was now represented by untaxed multinational net royalty payments, thus implying that Irish GDP was now circa 130% of Irish GNI (e.g. artificially inflated by 30%).[91]

The execution of Apple's Q1 2015 BEPS transaction implied that Irish GDP was now well over 155% of Irish GNI, exceeding even Luxembourg, and making it inappropriate for ongoing monitoring of the high level of Irish indebtedness. In response, in February 2017, the Central Bank of Ireland became the first of the major tax havens to abandon GDP and GNP as metrics, and replaced them with a new measure: Modified gross national income, or GNI* (or GNI Star).

At this point, multinational profit shifting doesn't just distort Ireland’s balance of payments; it constitutes Ireland’s balance of payments.

— Brad Setser and Cole Frank, Council on Foreign Relations, "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments", 25 April 2018[3]

The move was timely; in June 2018, research using 2015 data showed Ireland had become the world's largest tax haven (Zucman-Tørsløv-Wier 2018 list).[7][8][9]

Eurostat welcomed GNI*, but showed it could not eliminate all BEPS effects,[92] as the distortion in OECD reports assessing Irish indebtedness show.

See also

- Double Irish, Single Malt, and Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets BEPS tools

- EU illegal State aid case against Apple in Ireland

- International Financial Services Centre

- Economy of the Republic of Ireland

- Corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland

- Irish Fiscal Advisory Council

- Put on the green jersey

- Ireland as a tax haven

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 The Central Statistics Office (Ireland) further restated Irish 2015 data several times in 2017-18; by September 2018, Irish 2015 GDP was a further 6.4% above the 12 July 2016 restatement, as listed in Irish GDP versus Modified GNI (2009-2017)

- ↑ From a 9 January 2015 meeting with the EU Commission which was documented when the EU Commission published their full COMMISSION DECISION (S.A 38373), page 42 section 2.5.7 Apple's new corporate structure in Ireland as of 2015.[6]

References

- 1 2 CSO Statistical Release (12 July 2016). "National Income and Expenditure Annual Results 2015". Central Statistics Office (Ireland).

- 1 2 "Leprechaun Economics". Paul Krugman (Twitter). 12 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Brad Setser; Cole Frank (25 April 2018). "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations.

- 1 2 "CSO Press Release" (PDF). Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 12 July 2016.

As a consequence of the overall scale of these additions, elements of the results that would previously been published are now suppressed to protect the confidentiality of the contributing companies, in accordance with the Statistics Act 1993

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (24 January 2018). "What Apple did next". Economic Perspectives, University College Cork.

- 1 2 "COMMISSION DECISION of 30.8.2016 on STATE AID SA. 38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) implemented by Ireland to Apple" (PDF). EU Commission. 30 August 2016.

Brussels. 30.8.2016 C(2016) 5605 final. Total Pages (130)

- 1 2 Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Papers. p. 31.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

- 1 2 "Zucman:Corporations Push Profits Into Corporate Tax Havens as Countries Struggle in Pursuit, Gabrial Zucman Study Says". Wall Street Journal. 10 June 2018.

Such profit shifting leads to a total annual revenue loss of $200 billion globally

- 1 2 "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- ↑ Paul O’Donoghue (16 September 2016). "Ireland is trying to get off a Brazilian black list for tax havens". TheJournal.ie.

- ↑ Naomi Fowler (6 April 2017). "Tax haven blacklisting in Latin America". Tax Justice Network.

- ↑ "Leprechaun-proofing economic data". RTE News. 4 February 2017.

- 1 2 Seamus Coffey (28 January 2018). "Why €13bn Apple tax payment may not be the end of the story". The Sunday Business Post.

- 1 2 "EU asks for more details of Apple's tax affairs". The Times. 8 November 2017.

- ↑ Cliff Taylor (30 November 2017). "Trump's US tax reform a significant challenge for Ireland". Irish Times.

- ↑ "Shake-up of EU tax rules a 'more serious threat' to Ireland than Brexit". Irish Independent. 14 September 2017.

- ↑ Cliff Taylor (14 March 2018). "Why Ireland faces a fight on the corporate tax front". Irish Times.

- 1 2 Brad Setser (11 May 2018). "Ireland Exports its Leprechaun". Council on Foreign Relations.

Ireland has, more or less, stopped using GDP to measure its own economy. And on current trends [because Irish GDP is distorting EU-28 aggregate data], the eurozone taken as a whole may need to consider something similar.

- 1 2 "Quarter of Irish economic growth due to Apple's iPhone, says IMF". RTE News. 17 April 2018.

- 1 2 "iPhone exports accounted for quarter of Irish economic growth in 2017 - IMF". Irish Times. 17 April 2018.

- 1 2 Ian Guider (24 June 2018). "Irish Microsoft firm worth $100bn ahead of merger". The Sunday Business Post.

- ↑ "The World Bank Database: Real GDP Data". The World Bank. 2018.

- ↑ Fiona Reddan (12 September 2018). "Who still owes more, Ireland or the Greeks". Irish Times.

- ↑ "'Leprechaun economics' - Ireland's 26pc growth spurt laughed off as 'farcical'". Irish Independent. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Concern as Irish growth rate dubbed 'leprechaun economics'". Irish Times. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Blog: The real story behind Ireland's 'Leprechaun' economics fiasco". RTE News. 25 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Irish tell a tale of 26.3% growth spurt". Financial Times. 12 July 2016.

- ↑ ""Leprechaun economics" - experts aren't impressed with Ireland's GDP figures". thejournal.ie. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "'Leprechaun economics' leaves Irish growth story in limbo". Reuters News. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "'Leprechaun Economics' Earn Ireland Ridicule, $443 Million Bill". Bloomberg News. 13 July 2016.

- ↑ "Putting Ireland's health spending into perspective" (PDF). The Lancet. 391 (10123): 833. March 2018.

Similarly, health spending as a percentage of GDP declined sharply in 2015, despite an increase in health spending, as Irish GDP increased by 26% (a figure that spawned the phrase leprechaun economics)

- ↑ Paul Krugman (8 November 2017). "Leprechaun Economics and Neo-Lafferism". New York Times.

- ↑ Paul Krugman (4 December 2017). "Leprechauns of Eastern Europe". New York Times.

- ↑ Dermot O'Leary (21 April 2017). "Housing data reveals return of 'leprechaun economics'". Irish Times.

- ↑ Leonid Bershidsky (19 July 2017). "The U.S. Has a 'Leprechaun Economy' Effect, Too". Bloomberg.

- ↑ Aidan Regan; Samual Brazys (6 September 2017). "Celtic Phoenix or Leprechaun Economics? The Politics of an FDI-led Growth Model in Europe". New Political Economy. 23 (2): 223–238.

- ↑ Cormac Lucey (13 August 2018). "Multinationals' smoke and mirrors obscure our strong indigenous performance". Irish Management Institute.

The bulk of that decline occurred in 2015 when MFP in the FDI sector dropped by a leprechaun-like 57.2%. It begs the question, does ‘Official Ireland’ really understand what the multinationals are up to here?

- ↑ Zachary Basu (15 August 2018). "Europe moves on from financial crisis, but Greece is still recovering". AXIOS.

Its skyrocketing GDP is heavily skewed by "leprechaun economics," a term used to describe the tax inversion practices of corporations like Apple that base subsidiaries in Ireland.

- ↑ Cantillon (14 July 2018). "Does the CSO have another leprechaun on the loose?". Irish Times.

- ↑ Eoin Burke-Kennedy (17 March 2018). "Give me a crash course in .... Irish economic growth". The Irish Times.

Nobody believes our GDP numbers any more, not after a 26 per cent jump in 2015, which was famously derided as "leprechaun economics". Even the CSO cautions against viewing last year's [2017] 7.8 per cent jump as a reflection of real economic activity

- ↑ Aidan Regan; Samuel Brazys (March 2018). "Celtic Phoenix or Leprechaun Economics? The Politics of an FDI-led Growth Model in Europe". New Political Economy. 23 (2): 223–238.

- ↑ "Dail Eireann Oireachtas Debates: Search".

- ↑ "Economy grew by 'dramatic' 26% last year after considerable asset reclassification". RTE News. 12 July 2016.

- ↑ "Ireland Abolish Double Irish Tax Scheme". The Guardian. 14 October 2014.

Ireland has officially announced the phased abolition of its controversial “double Irish” tax scheme that has enabled multinationals such as Apple to dramatically cut down their tax bills

- ↑ "Brussels in crackdown on 'double Irish' tax loophole". The Financial Times. October 2014.

- ↑ Anthony Ting (October 2014). "Ireland's move to close the 'double Irish' tax loophole unlikely to bother Apple, Google". The Guardian.

First, existing companies incorporated in Ireland will enjoy a long “grandfather” period. In particular, the new rule will not be applicable to these companies – including the Irish subsidiaries of Google and Microsoft – until 2021

- ↑ "Handful of multinationals behind 26.3% growth in GDP". Irish Times. 12 July 2016.

A handful of multinational companies in the tech, pharma and aircraft leasing sectors were responsible for an extraordinary jump in Ireland’s headline rate of economic growth last year

- ↑ Patrick Honohan (13 July 2016). "The Irish National Accounts: Towards some do's and don'ts". irisheconomy.ie.

- ↑ Michael Connolly (November 2016). "Challenges of Measuring the Modern Global Economy" (PDF). Central Statistics Office (Ireland).

- 1 2 "Apple tax affairs changes triggered a surge in Irish economy". The Irish Examiner. 18 September 2016.

The Government has yet to admit that the enormous disruption to Irish GDP figures and the surge in corporate tax revenues was due to the actions of a single multi-national. [..] Karl Whelan, professor of economics at UCD, said a large part of the surge in corporate tax receipts and the huge GDP revisions can be attributed to the rearrangement of Apple’s tax affairs

- ↑ Tim Worstall (8 September 2016). "Absolutely Fascinating - Apple's EU Tax Bill Explains Ireland's 26% GDP Rise". Forbes Magazine.

Huge revisions to Irish GDP levels that led to “leprechaun economics” claims earlier this year were almost completely caused by Apple re-arranging its tax affairs after the Government closed off tax loopholes

- ↑ "'Leprechaun Economics' not all down to Apple move, insists CSO". Irish Independent. 9 September 2016.

Last night, CSO statistician Andrew McManus insisted that the earlier guidance had been correct. "There were a number of factors involved. That was the situation then and now," he said.

- ↑ Daniel Tierney (2017). "Finding "Gold" in Leprechaun Economics". MIT Sloan School of Management. p. 5,28,30.

- ↑ Pearse Doherty (November 2016). ""Leprechaun economics" has damaged the reputation of Ireland's economic data". Sinn Fein. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ "Key Economic Indicators". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). 2018.

- ↑ "Now 'Leprechaun Economics' puts Budget spending at risk". Irish Independent. 21 July 2016.

- ↑ "Leprechaun economics pushes Ireland's EU bill up to €2bn". Irish Independent. 30 September 2017.

- ↑ "Ireland to avoid EU €280m 'leprechaun economics' penalty". Irish Independent. 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "'Leprechaun economics': EU mission to audit 26% GDP rise". Irish Times. 19 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 J. Angerer; M. Hradiský; M. Magnus; A. Zoppé; M. Ciucci; J. Vega Bordell; M.T. Bitterlich (8 November 2016). "Economic Dialogue with Ireland Box 1: GDP statistics in Ireland: "Leprechaun economics"?" (PDF). EU Commission. p. 3.

- ↑ "Chairman, Fiscal Advisory Council: 'There's been a very strong recovery - we are now living within our means'". Irish Independent. 18 January 2018.

- ↑ "Minister Donohoe publishes Review of Ireland's Corporation Tax Code". Department of Finance. 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (30 June 2017). "REVIEW OF IRELAND'S CORPORATION TAX CODE, PRESENTED TO THE MINISTER FOR FINANCE AND PUBLIC EXPENDITURE AND REFORM" (PDF). Department of Finance (Ireland).

- ↑ Seamus Coffey Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (21 March 2016). "Apple Sales International–By the numbers". Economics Incentives, University College Cork.

- ↑ "Apple may have to repay millions from Irish government tax deal". The Guardian. 30 September 2016.

Seamus Coffey, an economics lecturer at University College Cork, who has examined Apple’s Irish tax affairs, said: “The EC can demand back payments for 10 years, which would take it back to 2004.”

- ↑ Brad Setser (30 October 2017). "Apple's Exports Aren't Missing: They Are in Ireland". Council on Foreign Relations.

- ↑ Naomi Fowler (25 June 2018). "New Report on Apple's New Irish Tax Structure". Tax Justice Network.

- ↑ Martin Brehm Christensen; Emma Clancy (21 June 2018). "Apple's Irish Tax Deals". European United Left–Nordic Green Left EU Parliament.

- ↑ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (18 July 2018). "When can we expect the next wave of IP onshoring?". Economics Incentives, University College Cork.

IP onshoring is something we should be expecting to see much more of as we move towards the end of the decade. Buckle up!

- ↑ Jesse Drucker; Simon Bowers (6 November 2017). "After a Tax Crackdown, Apple Found a New Shelter for Its Profits". New York Times.

- ↑ "BBC Panorama Special Paradise Papers Apple Secret Bolthole Revealed". BBC News. 6 November 2017.

- ↑ "Apple used Jersey for new tax haven after Ireland crackdown, Paradise Papers reveal". Independent. 6 November 2017.

- ↑ "Capital allowances for intangible assets". Irish Revenue. 15 September 2017.

- ↑ "Intangible Assets Scheme under Section 291A Taxes Consolidation Act 1997" (PDF). Irish Revenue. 2010.

- 1 2 "Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets under section 291A of the Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 (Part 9 / Chapter2)" (PDF). Irish Revenue. February 2018.

- ↑ "Tax break for IP transfers is cut to 80pc". Irish Independent. 11 October 2017.

- ↑ Cliff Taylor (8 November 2017). "Change in tax treatment of intellectual property and subsequent and reversal hard to fathom". Irish Times.

- ↑ Jack Horgan-Jones; Seamus Coffey (28 January 2018). "Apple tax bill could climb by €9bn as firms dig in". The Sunday Business Post.

- ↑ Pearse Doherty (25 January 2018). "Apple could owe billions more in tax due to its restructured tax arrangements since 2015". Sinn Fein.

- ↑ Sean Whelan (19 July 2016). "Making the most of leprechaun conomics". The Sunday Business Post.

- ↑ "Tim Cook: 'Apple is the largest taxpayer in Ireland'". TheJournal.ie. 30 August 2016.

- ↑ "An Analysis of 2015 Corporation Tax Returns and 2016 Payments" (PDF). Revenue Commissioners. April 2017.

- ↑ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (17 July 2018). "Capital Allowances and companies with Net Trading Income that is negative or nil". Economic Incentives, University College Cork.

And we see that after the application of losses, and most importantly, capital allowances, the resulting net trading income of these companies with almost €50 billion of Gross Trading Profits in 2016 was zero

- ↑ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (17 July 2018). "The 2016 Aggregate Corporation Tax Calculation". Economic Incentives, University College Cork.

And, again it highlights, that although the surge in CT receipts may have happened in the same year as the jump in GDP, they are not necessarily directly related. As with lots of things lately, capital allowances play a central role in this and it is to them that we will turn next

- ↑ James R. Hines Jr.; Eric M. Rice (February 1994). "FISCAL PARADISE: FOREIGN TAX HAVENS AND AMERICAN BUSINESS" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Economics (Harvard/MIT). 9 (1).

We identify 41 countries and regions as tax havens for the purposes of U. S. businesses. Together the seven tax havens with populations greater than one million (Hong Kong, Ireland, Liberia, Lebanon, Panama, Singapore, and Switzerland) account for 80 percent of total tax haven population and 89 percent of tax haven GDP.

- ↑ "IDEAS/RePEc Database".

Tax Havens by Most Cited

- 1 2 James R. Hines Jr. (2010). "Treasure Islands". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 4 (24): 103–125.

Table 2: Largest Tax Havens

- ↑ Dhammika Dharmapala (2014). "What Do We Know About Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature". University of Chicago.

- ↑ Seamus Coffey, Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (29 April 2013). "International GNI to GDP Comparisons". Economic Incentives.

- ↑ Heike Joebges (January 2017). "CRISIS RECOVERY IN A COUNTRY WITH A HIGH PRESENCE OF FOREIGN-OWNED COMPANIES: The Case of Ireland" (PDF). IMK Macroeconomic Policy Institute, Hans-Böckler-Stiftung.

- ↑ "Europe points finger at Ireland over tax avoidance". Irish Times. 7 March 2018.

- ↑ SILKE STAPEL-WEBER; JOHN VERRINDER (December 2017). "Globalisation at work in statistics — Questions arising from the 'Irish case'" (PDF). EuroStat. p. 31.

Nevertheless the rise in [Irish] GNI is still very substantial because the additional income flows of the companies (interest and dividends) concerned are considerably smaller than the value added of their activities

External links

- Irish Central Statistics Office

- Irish Fiscal Advisory Council

- Seamus Coffey University College Cork

- Apple's BEPS tool explained, Irish Times Video

- Finding "Gold" in Leprechaun Economics, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Spring 2017

.jpeg)