TRS-80

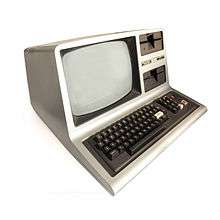

TRS-80 Model I with Expansion Interface | |

| Manufacturer | Tandy Corporation |

|---|---|

| Type | Home computer |

| Release date | August 3, 1977[1] |

| Discontinued | January 1981 |

| Units sold | 100,000+ (As of October 1979)[2] |

| Operating system | TRSDOS, NewDos/80 |

| CPU | Zilog Z80 @ 1.774 MHz |

| Memory | 4 KB ~ 48 KB |

The TRS-80 Micro Computer System (TRS-80, later renamed the Model I to distinguish it from successors) is a desktop microcomputer launched in 1977 and sold by Tandy Corporation through their Radio Shack stores. The name is an abbreviation of Tandy/Radio Shack, Z-80 microprocessor.[3] It was one of the earliest mass-produced and mass-marketed retail personal computers.[4]

The TRS-80 featured a full-stroke QWERTY keyboard, the new Zilog Z80 processor (rather than the more common Intel 8080), 4 KB DRAM standard memory (when many 8-bit computers shipped with only 1 KB RAM), small size and desk footprint, floating-point BASIC programming language, standard 64-character/line video monitor, and a starting price of US$600[1] (equivalent to US$2400 in 2017).

An extensive line of upgrades and add-on hardware peripherals for the TRS-80 was developed and marketed by Tandy/Radio Shack. The basic system could be expanded with up to 48 KB of RAM (in 16 KB increments), and up to four floppy disk drives and/or hard disk drives. Tandy/Radio Shack provided full-service support including upgrade, repair, and training services in their thousands of stores worldwide.

By 1979, the TRS-80 had the largest selection of software in the microcomputer market.[5] Until 1982, the TRS-80 was the best-selling PC line, outselling the Apple II series by a factor of 5 according to one analysis.[3]

In mid-1980, the broadly compatible TRS-80 Model III was released. The Model I was discontinued shortly thereafter, primarily due to stricter FCC regulations on radio-frequency interference to nearby electronic devices.[6][7] In April 1983 the Model III was succeeded by the compatible Model 4.

Following the original Model I and its compatible descendants, the TRS-80 name later became a generic brand used on other technically unrelated computer lines sold by Tandy, including the TRS-80 Model II, TRS-80 Model 2000, TRS-80 Model 100, TRS-80 Color Computer and TRS-80 Pocket Computer.

History

In the mid-1970s, Tandy Corporation's Radio Shack division was a successful American chain of more than 3,000 electronics stores. After buyer Don French purchased a MITS Altair kit computer, he began designing his own and showed it to vice president of manufacturing John Roach. Although the design did not impress Roach, the idea of selling a microcomputer did. When the two men visited National Semiconductor in California in mid-1976, Steve Leininger's expertise on the SC/MP microprocessor impressed them. National executives refused to provide Leininger's contact information when French and Roach wanted to hire him as a consultant, but they found Leininger working part-time at Byte Shop and he and French began working together in June 1976. The company envisioned a kit, but Leininger persuaded the others that because "too many people can't solder", a preassembled computer would be better.[8][9][10]

Tandy had 11 million customers that might buy a microcomputer, but it would be much more expensive than the US$30 median price of a Radio Shack product, and a great risk for the very conservative company.[10] Executives feared losing money as Sears did with Cartrivision,[11] and many opposed the project; one executive told French, "Don't waste my time—we can't sell computers." As the popularity of CB radio—at one point comprising more than 20% of Radio Shack's sales—declined, however, the company sought new products. In December 1976 French and Leininger received official approval for the project but were told to emphasize cost savings; for example, leaving out lowercase characters saved US$1.50 in components and reduced the retail price by US$5. In February 1977 they showed their prototype, running a simple tax-accounting program, to Charles Tandy, head of Tandy Corporation. The program quickly crashed as the computer could not handle the US$150,000 figure that Tandy typed in as his salary, and the two men added support for floating-point math to its Tiny BASIC to prevent a recurrence. After the demonstration Tandy revealed that he had already leaked the computer's existence to the press, so the project was approved.[10][12]

MITS sold 1,000 Altairs in February 1975, and was selling 10,000 a year. Leininger and French suggested that Radio Shack could sell 50,000 computers,[13] but others disagreed and suggested 1,000 to 3,000 per year at the target US$199 price. Roach persuaded Tandy to agree to build 3,500—the number of Radio Shack stores—so that each store could use a computer for inventory purposes if they did not sell.[5][8][9][12]

Having spent less than US$150,000 on development, Radio Shack announced the TRS-80 (Tandy Radio Shack) at a New York City press conference on August 3, 1977. It cost US$399 ($1611 today), or US$599 ($2419 today) with a 12" monitor and a Radio Shack tape recorder as datacassette storage; the most expensive product Radio Shack previously sold was a US$500 stereo. The company hoped that the new computer would help Radio Shack sell higher-priced products, and improve its "schlocky" image among customers. Small businesses were the primary target market, followed by educators, then consumers and hobbyists; despite its hobbyist customer base, Radio Shack saw them as "not the mainstream of the business" and "never our large market".[9][14][13][15][16]

Although the press conference did not receive much media attention because of a terrorist bombing elsewhere in the city, the computer received much more publicity at the Personal Computer Faire in Boston two days later. A front-page Associated Press article discussed the novelty of a large consumer-electronics company selling a home computer that could "do a payroll for up to 15 people in a small business, teach children mathematics, store your favorite recipes or keep track of an investment portfolio. It can also play cards." Six sacks of mail arrived at Tandy headquarters asking about the computer, over 15,000 people called to purchase a TRS-80—paralyzing the company switchboard—and 250,000 joined the waiting list with a $100 deposit.[9][5][13][17][18]

Despite the internal skepticism, Radio Shack aggressively entered the market. The company advertised "The $599 personal computer" as "the most important, useful, exciting, electronic product of our time".[19] Company president Lewis Kornfeld stated when announcing the TRS-80, "This device is inevitably in the future of everyone in the civilized world—in some way—now and so far as ahead as one can think", and Tandy's 1977 annual report called the computer "probably the most important product we've ever built in a company factory". Unlike competitor Commodore—which had announced the PET several months earlier but had not yet shipped any—Tandy had its own factories and distribution network, and even small towns had Radio Shack stores. The company announced plans to be selling by Christmas a range of peripherals and software for the TRS-80, began shipping computers by September, and opened its first computer-only store in October. Still forecasting 3,000 sales a year, Radio Shack sold over 10,000 TRS-80s Model Is in its first one and a half months of sales, and over 200,000 during the product's lifetime;[18][8][20][9][12][5][16][11][21]:4[14] one entered the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.[22] By mid-1978 the waits of two months or more for delivery were over,[23] and the company could state in advertisements that TRS-80 was "on demonstration and available from stock now at every Radio Shack store in this community!".[19]

The first units, ordered unseen, were delivered in November 1977, and rolled out to the stores the third week of December. The line won popularity with hobbyists, home users, and small-businesses. Tandy Corporation's leading position in what Byte Magazine called the "1977 Trinity" (Apple, Commodore and Tandy) had much to do with Tandy's retailing the computer through more than 3,000 of its Radio Shack storefronts in the USA.[24] Tandy claimed it had "7000 [Radio Shack] stores in 40 countries".[25] The pre-release price for the basic system (CPU/keyboard and video monitor) was US$500 and a US$50 deposit was required, with a money-back guarantee at time of delivery.

By 1978, Tandy/Radio Shack promoted itself as "The Biggest Name in Little Computers".[26][25] By 1980 InfoWorld described Radio Shack as "the dominant supplier of small computers".[27] Kilobaud Microcomputing estimated that it was selling three times as many computers as Apple Computer, with both companies ahead of Commodore.[28] By 1981 hundreds of small companies produced TRS-80 software and accessories,[29] and Adam Osborne described Tandy as "the number-one microcomputer manufacturer" despite having "so few roots in microcomputing".[30] Roach became Tandy's CEO that year, Leininger became director of strategic planning, and French founded a software company. However, selling computers did not change the company's "schlocky" image; the Radio Shack name embarrassed business customers, and Tandy executives disliked the "Trash-80" nickname for its products. By 1984, computers accounted for 35% of sales and the company had 500 Tandy Radio Shack Computer Centers.[8][12][16][31]

Following the Model III launch in mid-1980, Tandy initially claimed that the Model I had not been dropped.[32] However, it had been discontinued by the end of the year. Tandy cited one of the main reasons as being the prohibitive cost of redesigning it to meet stricter FCC regulations covering the significant levels of radio-frequency interference emitted by the original design.[7][6] The Model I radiated so much interference that, while playing games, an AM radio placed next to the computer could be used to provide sounds.[33]

Hardware

The Model I combined the mainboard and keyboard into one unit, which became a design trend in the 8-bit microcomputer era, although the Model I had a separate power supply unit. It used a Zilog Z80 processor clocked at 1.77 MHz (later models were shipped with a Z80A). The initial Level I machines shipped in late 1977-early 1978 had only 4k of RAM. After the Expansion Interface and Level II BASIC were introduced in mid-1978, RAM configurations of 16k and up were offered (the first 16k was in the Model I itself and the remaining RAM in the EI).

The OS ROMs, I/O area, video memory and OS work space occupy the first 16 kB of memory space on the Model I, the remaining 48 kB of the 64 kB memory map space is available for program use, subject to the amount of physical RAM installed. Although the Z80 CPU can use port-based I/O, the Model I's I/O is memory-mapped aside from the cassette tape and RS-232 serial ports.

The memory map of the Model I and III rendered them incompatible with standard CP/M OS which loaded at hexadecimal address $0000 with TPA (Transient Program Area) starting at $0100. A customized version of CP/M was available for both computers, but the intended portability advantage of CP/M was nullified.[34]

Keyboard

The keyboard design was unusual. Instead of transferring data through an I/O chip, the hardware mapped the keyboard to dedicated locations in the processor's memory. Performing a read from the keyboard area of the memory would return the state of a particular set of keys.

Many users complained about the TRS-80 Model I keyboards, which used mechanical switches and suffered from "keyboard bounce", resulting in multiple letters being typed per keystroke.[35] The problem was described in Wayne Green's editorial in the first issue of 80 Micro.[36] A Keyboard De-Bounce tape was distributed, which altered the system software to reduce the effect of bounce and to slow down polling of the keyboard. The change was subsequently added to a firmware ROM revision. The keyboard hardware was also modified to minimize bounce.

The root cause of the key bounce was found to be dust, dirt, etc., entering the keyboard's switches, and contaminating the switch contacts. This problem was most common among heavy smokers (smoke and ash particles). The key switches could be cleaned, rectifying the problem, but the bounce would be back again when the keyboard was re-exposed to the contaminating environment.

Later production runs of the Model I computer replaced the nameplate with a numeric keypad. Older versions could be upgraded with a numeric keypad add-on by keyboard replacement, which also remedied the key bounce problem because other parts of the system would be updated by the service technician during installation.

Model II, III and later came with flawless keyboards that included numeric keypads.

Video and audio

The TRS-80 Model I was accompanied by a modified RCA black-and-white television. The color of the screen text is faintly blue (the standard P4 phosphor used in black-and white televisions). Green and amber filters, or replacement tubes to reduce eye fatigue were popular aftermarket items. Later models came with a green-on-black display.

Complaints about the video display quality were common. As Green wrote, "hells bells, [the monitor] is a cheap black and white television set with a bit of conversion for computer use".[36] (The computer could be purchased without the Radio Shack monitor.)[18] CPU access to the screen memory caused visible flicker. The bus arbitration logic blocked video display refresh (video RAM reads) during CPU writes to the VRAM, causing a short black line. This had little effect on normal BASIC programs, but fast programs made with assembly language could be affected. Software authors worked to minimize the effect. Notwithstanding the primitive display hardware, many arcade-style games were available for the Tandy TRS-80.

Because of bandwidth problems in the interface card that replaced the TV's tuner, the display would lose horizontal sync if large areas of white were displayed. A simple half-hour hardware fix could correct that.

Like the Apple II, an unmodified Model I cannot display lowercase letters. The video RAM used 2102 SRAM chips, which were 1kx1, but the PCB had just 7 of them installed, allowing only 128 characters to be displayed (0 to 127). Leaving out a seventh chip saved $1 in manufacturing costs, which would have increased the purchase price of the computer by $15. By installing a seventh 2102 (done by piggybacking it onto chip #6), it was possible to display all 256 characters (which includes lowercase letters). The 1978 manual for the popular word processor Electric Pencil came with instructions for modifying the computer. Although the modification needed to be disabled for Level II BASIC, its design became the industry standard and was widely sold in kit form,[37] along with an eighth 2102 chip with descenders for the lowercase letters. Later models came with the hardware for the lowercase character set to be displayed with descenders.

Since there is only 1k of video RAM, the Model I's display has 64x16 characters instead of the more common 40x25 or 80x25. Both 64x16 and 32x16 video modes are supported, which is in contrast to 40x25 used by Apple and 80x24 used by some dumb terminals. The choice of 64x16 was part in economics, part in physics and part in usability. To support 80x24, twice as much static ram would be required (7 additional RAM chips, 9 chips total with the extra address decoding needed), plus there was no room on the board to put any extra chips. The Model I was originally intended to be used with a user supplied black and white television, what could physically be displayed on a 1970s black-and-white TV. Color TVs were still a luxury item in the '70s. With no color burst signal and with the RF stage skipped, a B&W TV could easily display up to 64 columns well, but 80 columns would create an unviewable image. With 1K of RAM address space, a maximum of 16 lines are possible. From a usability standpoint, 16 lines of 64 characters was more versatile than 24 lines of 40 characters, as 64 characters is the full width of a typewritten page (at the typical typewriter's 10 characters per inch with 1 inch page borders commonly used at the time).

With higher density RAM chips and dedicated purpose build monitors, higher resolution crisp displays are obtainable—80x24 character displays were available in the Model II, Model 4, and later systems.

The Model I has no built-in speaker. Square wave tones can be produced by outputting data to the cassette port and plugging an amplifier into the cassette "Mic" line. Most games used this ability for sound effects. An adapter was available to use Atari joysticks.[38]

Peripherals

Cassette tape drive

User data was originally stored on cassette tape. Radio Shack's model CTR-41 cassette recorder was included with the US$599 package.[21]:3–4 The software-based[8] cassette tape interface was slow and erratic;[35] Green described it as "crummy ... drives users up the wall", and the first issue of 80 Micro had three articles on how to improve cassette performance.[36] It was sensitive to audio volume,[18] and the machine gave only a crude indication as to whether the correct volume was set, via a blinking character on screen while data was being loaded. To find the correct volume at first use, the load was started and the volume was adjusted until the TRS-80 picked up the data. Then it was halted to rewind the tape and restart the load. Users were instructed to save multiple copies of a software program file, especially if audio tape cassettes instead of certified data tape was used. Automatic gain control or indicator circuits could be constructed to improve the loading process (the owner's manual provided complete circuit diagrams for the whole machine, including the peripheral interfaces, with notes on operation).

An alternative to using tape was data transmissions from the BBC's Chip Shop programme in the UK, which broadcast software for several different microcomputers over the radio. A special program was loaded using the conventional tape interface. Then the radio broadcast was connected to the cassette tape interface. Tandy eventually replaced the CTR-41 unit with the CTR-80 which had built-in AGC circuitry (and no volume control). This helped the situation, but tape operation was still unreliable.

TRS-80 Model I's with Level I BASIC read and wrote tapes at 250 baud (about 30 bytes per second); Level II BASIC doubled this to 500 baud (about 60 bytes per second). Some programmers wrote machine-language programs that would increase the speed to up to 2,000 bits per second without a loss of reliability on their tape recorders. With the Model III and improved electronics in the cassette interface, the standard speed was increased to 1,500 baud that worked quite reliably on most tape recorders.

For loading and storing data from tape, the CPU created the sound by switching the output voltage between three states, creating crude sine wave audio.

The first version of the Model I also had a hardware problem that complicated loading programs from cassette recorders. Tandy offered a small board which was installed at a service center to correct the issue. The ROMs in later models were modified to correct this.

Model I Expansion interface

Only the Model I used an Expansion interface; all later models had everything integrated in the same housing.

The TRS-80 did not use the S-100 bus like other early 8080 and Z80-based computers.[9] A proprietary Expansion Interface (E/I) box, which fit under the video monitor and served as its base, was offered instead. Standard features of the E/I were a floppy disk controller, Centronics parallel port for a printer, and additional cassette connector. Optionally, an extra 16 or 32 kB of RAM could be installed and a daughterboard with an RS-232 port.[39] The 40-conductor expansion connector was passed through to a card edge connector, which permitted the addition of external peripherals such as an outboard hard disk drive, a voice synthesizer, or a VOXBOX voice recognition unit.[40][41]

Originally, printing with the Model I required the expansion interface, but later Tandy made an alternative parallel printer interface available.

The Model I Expansion Interface was the most troublesome part of the TRS-80 Model I system. It went through several revisions. The E/I connected to the CPU/keyboard with a 6-inch ribbon cable which was unshielded against RF interference and its card edge connector tended to oxidize due to its base metal contacts. This demanded periodic cleaning with a pencil eraser in order to avoid spontaneous reboots, which contributed to its "Trash-80" sobriquet. Aftermarket connectors plated with gold solved this problem permanently. Software developers also responded by devising a recovery method which became a standard feature of many commercial programs. They accepted an "asterisk parameter", an asterisk (star) character typed following the program name when the program is run from the TRSDOS Ready prompt. When used following a spontaneous reboot (or an accidental reset or program crash), the program loaded without initializing its data area(s), preserving any program data present from the pre-reboot session. Thus, for example, if a Visicalc user suffered a spontaneous reboot, to recover his data he would enter "VC *" at the TRSDOS Ready prompt, and Visicalc would restore the previous computing session intact.

The power button on the EI was also somewhat difficult to operate as it was recessed so as to guard against the user accidentally hitting it and turning it off while in use. A pencil eraser or similar object would be used to depress the power button and the EI had no power LED, making it difficult to determine if it was running or not.

The expansion unit required a second power supply, identical to the base unit power supply. An interior recess held both supplies.

The user was instructed to power on and power off all peripherals in proper order to avoid corrupting data or potentially damaging hardware components. The manuals for the TRS-80 stipulated turning on the monitor first, then any peripherals attached to the EI (if multiple disk drives were attached, the last drive on the chain was to be powered on first and work down from there), the EI, and the computer last. When powering down, the computer was to be turned off first, followed by the monitor, EI, and peripherals. In addition, users were instructed to remove all disks from the drives during power up or down (or else leave the drive door open to disengage the read/write head from the disk) because of potential spurious electrical activity being generated (a common problem on many early floppy drives).

The EI displayed a screen full of garbage characters on power up and unless a bootable system disk was present in Drive 0, it would hang there until the user either pressed the Reset button on the back of the computer, which would cause it to attempt to boot the disk again, or Break+Reset was pressed, which would drop the computer into BASIC. Due to the above-mentioned problems with potentially corrupting disks, it was recommended to power up to the garbage screen with the disk drives empty, insert a system disk, and then hit Reset.

InfoWorld compared the cable spaghetti connecting the TRS-80 Model I's various components to the snakes in Raiders of the Lost Ark.[35] Radio Shack offered a "TRS-80 System Desk"[42] that concealed nearly all the cabling. It could accommodate the complete computer system plus up to four floppy drives and the Quick Printer. Since the cable connecting the expansion interface carried the system bus, it was kept short (about 6 inches). The user had no choice but to place it directly behind the computer with the monitor on top of it. This caused problems for a non-Tandy monitor whose case did not fit the mounting holes. Also, the friction fit of the edge connector on the already short interconnect cable made it possible to disconnect the system bus from the CPU if either unit was inadvertently moved during operation.

Floppy disk drives

Radio Shack introduced floppy drives in July 1978, about six months after the Model I went on sale. The Model I disk operating system TRSDOS was written by Randy Cook under license from Radio Shack; Randy claims to have been paid $3000 for it. The first version released to the public was a buggy v2.0, this was quickly replaced by v2.1.[43] required buying the Expansion Interface, which included a single-density floppy disk interface (with a formatted capacity of 85k) based on the Western Digital 1771 single-density floppy disk controller chip. The industry standard Shugart Associates SA-400 minifloppy disk drive was used. Four floppy drives could be daisy-chained to the Model I. The last drive in the chain was supposed to have a termination resistor installed but often it was not needed as it was integrated into later cables.[44]

Demand for Model I drives greatly exceeded supply at first.[36] Unfortunately, it was unreliable, partly since the interface lacked an external data separator (buffer).[35] The early version(s) of TRS-DOS were also buggy, no help to the Western Digital FD1771 chip that could not reliably report its status for several instruction cycles after it received a command. A common method of handling the delay was to issue a command to the 1771, perform several "NOP" instructions, then query the 1771 for the result. Early TRS-DOS neglected the required yet undocumented wait period, and thus false status was often returned to the OS, generating random errors and crashes. Once the 1771 delay was implemented, it was fairly reliable.

In 1981, Steve Ciarcia published in BYTE the design for a homemade, improved expansion interface with additional RAM and a disk controller for the TRS-80.[45]

A data separator and a double density disk controller (based on the WD 1791 chip) were made by Percom (a Texas peripheral vendor), LNW, Tandy and others. The Percom Doubler added the ability to boot and use Double Density Floppies using a Percom-modified TRSDOS called DoubleDOS. The LNDoubler added the ability to read and write from 5¼" diskette drives for a total of 1.2 MB storage. Near the end of the Model I's lifespan in 1982, upgrades were offered to replace its original controller with a double density one.

The disk drives offered on the Model I were Shugart SA-400s which supported 35 tracks and was the sole 5.25" drive on the market in 1977-78. By 1979, other manufacturers began offering drives. Models 3/4/4P used Tandon TM-100 40-track drives. The combination of 40 tracks and double-density gave a capacity of 180 kilobytes per single-sided floppy disk. The use of index-sync meant that a "flippy disk" required a second index hole and write-enable notch. One could purchase factory-made "flippies". Some software publishers formatted one side for Apple systems and the other for the TRS-80.

The usual method of connecting floppy drives involved setting the drive letter via jumper blocks on the drive controller board, however Tandy opted for a slightly more user-friendly technique where all four select pins on the drives were jumpered and the ribbon cable was missing the Drive Select line, thus the user did not need to worry about moving jumpers around depending on which position on the chain a drive was in.

A standard flat floppy ribbon cable was perfectly usable on the Model I, in which case the drives would have to be jumpered to their number on the chain, or even an IBM PC "twist" cable, which required setting each drive number to 1, but would only permit two drives on the chain.

Although third party DOSes allowed the user to define virtually any floppy format he wanted, the "lowest common denominator" format for TRS-80s was the baseline single density, single sided, 35-40 track format of the Model I.

Third-party vendors like Aerocomp made available double-sided and 80 track 5-1/4 inch and later 3-1/2 inch floppy drives with up to 720 kB of storage each. These new drives were all half-height and therefore required different or modified drive housings.

Exatron Stringy Floppy

An alternative to cassette tape and floppy disk storage was provided by a company called Exatron. The device was a continuous loop tape drive, dubbed the "stringy floppy" or ESF. It required no Expansion Interface, plugging directly into the TRS-80's 40-pin expansion bus, was much less expensive than a floppy drive, could read and write random-access data like a floppy drive unlike a cassette tape, and it transferred data at up to 14,400 baud. Exatron tape cartridges stored over 64 kB of data. The ESF could coexist with the TRS-80 data cassette drive. It was popular with TRS-80 enthusiasts, selling over 4000 units by 1981. Exatron also made a complementary RAM expansion board that installed in the TRS-80 keyboard to increase memory to 48 kB without the E/I.[46]

Hard drive

Radio Shack introduced a 5 MB external hard disk for the TRS-80 Model III/4 in 1983. It was the same hard disk unit offered for the Model II line, but came with OS software for Model III/4. An adapter was required to connect it to the Model I's E/I.[47] The unit was about the same size as a modern desktop computer enclosure. Up to four hard disks could be daisychained for 20 MB of storage. The LDOS operating system by Logical Systems was bundled, which provided utilities for managing the storage space and flexible backup. The initial retail price for the first (primary) unit (US$2495) is equivalent to US$6100 in 2017. Later, a 15MB hard disk was offered in a white case, which could be daisychained for up to 60 MB. Like most hard disks used on 8-bit machines, there was no provision for subdirectories, but the DiskDISK utility was a useful alternative that could create virtual hard disk ".DSK" files that could be mounted as another disk drive, and used like a subdirectory would. To display the directory/contents of an unmounted DiskDISK virtual disk file, a shareware DDIR "Virtual Disk Directory Utility"[48] program was commonly used.

Printers

The "Quick Printer",[49] was an unusual electrostatic rotary printer that scanned the video memory through the bus connector, and printed an image of the screen onto aluminum-coated paper in about one second. Unfortunately, it was incompatible with both the final, buffered version of the expansion interface, and with the "heartbeat" interrupt used for the real-time clock under Disk BASIC. This could be overcome by using special cabling, and by doing a "dummy" write to the cassette port while triggering the printer.

Two 3rd party printers were for 57 mm metal coated paper, selling for approximately DM 600 in Germany, and a dot-matrix printer built by Centronics for normal paper, costing at first DM 3000, later sold at approximately DM 1500 in some stores. It had only 7 pins, so letters with descenders such as lowercase "g" did not reach under the baseline, but were elevated within the normal line.

Radio Shack offered an extensive line of printers for the TRS-80 family, ranging from basic 9-pin dot matrix units to large wide-carriage line printers for professional use, daisy-wheel printers, ink jet printers, laser printers and color plotters. All had a Centronics-standard interface and after the introduction of the Color Computer line in 1980, many also had a connector for the CoCo's serial interface.

Software

BASIC

Three versions of the BASIC programming language were produced for the Model I. Level I BASIC fit in 4 KB of ROM, and Level II BASIC fit into 12 KB of ROM. Level I was single precision only and had a smaller set of commands. Level II introduced double precision floating point support and had a much wider set of commands. Level II was further enhanced when a disk system was added, allowing for the loading of Disk BASIC.[9]

Level I BASIC was based on Li-Chen Wang's free Tiny BASIC with some additional functions added by Radio Shack.[11] It had an excellent manual[9][51][52]—the User's Manual for Level 1 by David A. Lien—which presented lessons on programming with text and humorous cartoons, making the subjects very easy to understand. Lien wrote that it was "written specifically for people who don't know anything about computers ... I want you to have fun with your computer! I don't want you to be afraid of it, because there is nothing to fear".[53][18] Level I BASIC had only two string variables (A$ and B$), 26 numeric variables (A – Z) and one array, A(). Code for functions like SIN(), COS() and TAN() was not included in ROM but printed at the end of the book. The only error messages were: "WHAT?" for syntax errors, "HOW?" for arithmetic errors such as division by zero, and "SORRY" for out of memory errors.

Level I BASIC was not tokenized—reserved words were stored literally. In order to maximize the code that could be crammed into 4K of memory users could enter abbreviations for reserved words. For example, writing "P." instead of "PRINT" thus saving 3 bytes.

Level II BASIC, introduced in mid-1978, was licensed from Microsoft and was required to use the expansion bus and disk drives. Radio Shack had always intended for Level I BASIC to merely be a stopgap until Level II was ready and the very first brochure for the Model I in January 1978 mentioned that Level II BASIC was "coming soon". It was a cut-down version of the 16k Extended BASIC, since the Model I had 12k of ROM space. According to Bill Gates, "It was a sort of intermediate between 8k BASIC and Extended BASIC. Some features from Extended BASIC such as descriptive errors and user defined functions were not included, but there were double precision variables and the PRINT USING statement that we wanted to get in. The entire development of Level II BASIC took about four weeks from start to finish." The accompanying manual was more terse and technical than the Level I manual. Original Level I BASIC-equipped machines could be retrofitted to Level II through a ROM replacement performed by Radio Shack for a fee (originally $199). Users with Level I BASIC programs stored on cassette had to convert these to the tokenized Level II BASIC before use. A utility for this was provided with the Level II ROMS.

Disk BASIC added the ability to perform disk I/O, and in some cases (NewDos/80, MultiDOS, DosPlus, LDOS) added powerful sorting, searching, full screen editing, and other features. Level II BASIC reserved some of these keywords and issued a "?L3 ERROR", suggesting a behind-the-scenes change of direction intervened between the creation of the Level II ROMs and the introduction of Disk BASIC.

Microsoft also marketed an enhanced BASIC called Level III BASIC written by Bill Gates,[54] that was supplied on a cassette tape. The cassette contains a "Cassette File" version on one side and a "disk file" version on the second side for disk system user's (which was to be saved to disk).[55] Level III BASIC added most of the functions in the full 16 KB version of BASIC plus many other TRS-80 specific enhancements. Many of Level III BASIC's features were included in the TRS-80 Model III's Level II BASIC and disk BASIC.

Level I BASIC was still offered on the Model I in either 4k or 16k configurations after the introduction of Level II BASIC.

Other applications

Blackjack and backgammon came with the TRS-80 for free, and at its debut Radio Shack offered four payroll, personal finance, and educational programs, all on cassette.[9][21]:3 While Radio Shack franchise stores sold third-party products, company-owned stores were at first prohibited from reselling products not sold by Radio Shack itself.[56][57] Its own products' quality was often poor. A critical 1980 80 Micro review of a text adventure described it as "yet another example of Radio Shack's inability to deal with the consumer in a consumer's market". The magazine added, "Sadly, too, as with some other Radio Shack programs, the instructions seem to assume that the reader is either a child or an adult with the mentality of a slightly premature corned beef."[58]

Green stated that year that although "there are more programs for the 80 than for all other systems combined" because of the computer's large market share, "Radio Shack can't advertise this because they are trying as hard as they can to keep this fact a secret from their customers. They don't want the TRS-80 buyers to know that there is anything more than their handful of mediocre programs available", many of which "are disastrous and, I'm sure, doing tremendous damage to the industry".[59][60] An author wrote in a 1979 article on the computer's "mystery of machine language graphics control" that "Radio Shack seems to hide the neat little jewels of information a hobbyist needs to make a treasure of the TRS-80". He stated that other than the "excellent" Level I BASIC manual "there has been little information until recently ... TRS-80 owners must be resourceful", reporting that the computer's "keyboard, video, and cassette" functionality were also undocumented.[51] The first book "authorized" by Tandy with technical information on TRSDOS for the Model I did not appear until after the computer's discontinuation.[57] By 1982 the company admitted—after no software appeared for the Model 16 after five months—that it should have, like Apple, encouraged third-party developers of products like the killer app VisiCalc.[61] (A lengthy 1980 article in a Tandy publication introducing the TRS-80 version of VisiCalc did not mention that the spreadsheet had been available for the Apple II for a year.[62]) By 1985 the company's Ed Juge stated that other than Scripsit and DeskMate, "we intend to rely mostly on 'big-name', market proven software from leading software firms".[63] A full suite of office applications became available from the company and others, including the VisiCalc and Multiplan spreadsheets and the Lazy Writer, Electric Pencil, and Scripsit word processors.

Despite the TRS-80's limited graphics and sound capability, independent software companies such as Big Five Software produced unlicensed versions of arcade games like Namco's Galaxian, Atari's Asteroids, and Exidy's Targ.[38] Some companies ported games from other home computers of the era, such as the original Zork adventure game. There were also many games unique to the TRS-80, including shooters like Cosmic Fighter and Defence Command and strange experimental programs such as Dancing Demon,[64] a game in which the player composed a song for a devil and choreographed his dance steps to the music.[65] Microchess for the Model I had three levels of play and could be run in the 4kb of memory that was standard with this model.

Utility software such as Stewart Software's Toolkit offered the first sorted directory, decoding or reset of passwords, and the ability to eliminate parts of TRSDOS that were not needed in order to free up floppy disk space. They also produced the On-Line 80 BBS, a TRSDOS based Bulletin Board System.

Perhaps because of the lack of information on TRSDOS,[57] by 1982 perhaps more operating systems existed for the TRS-80 than for any other computer.[66] TRSDOS was limited in its capabilities, since like Apple DOS 3.3 on the Apple II, it was mainly conceived of as a way of extending BASIC to support disk drives. Numerous alternative OSes appeared, including NewDOS, a third-party rival sold by a company called Apparat Personal Computers, which went out of business in 1987. Others included DoubleDOS, DOSPlus, MicroDOS, NEWDOS/80, UltraDOS (later called Multidos), and VTOS. The last versions (6.x) of TRSDOS were actually renamed LS-DOS (aka LDOS).

CP/M became a standard OS for business use on Z80-based machines, and versions ran on all TRS-80s. Omikron Systems' Mappers board remapped the BASIC ROM to run unmodified CP/M programs on the Model I.[67]

Reception

Dan Fylstra, among the first owners, wrote in BYTE in April 1978 that as an "'appliance' computer ... the TRS-80 brings the personal computer a good deal closer to the average customer", suitable for home and light business use. He concluded that it "is not the only alternative for the aspiring personal computer user, but it is a strong contender."[18] Jerry Pournelle wrote in 1980 that "the basic TRS-80 is a lot of computer for the money. It comes ready to run right out of the box, and it can be set up by three boys – ages 9, 11, and 13 ... The Tandy/Radio Shack documentation is excellent, and there are a lot of good programs available". He noted that while "just about every component of my TRS-80 has taken a trip to the local store to be fixed", "none of that cost me anything; it wasn't even inconvenient, especially with local Radio Shacks all over the place ... Given the price of the TRS-80, Tandy's quality control is better than you'd expect." Pournelle criticized the quality of Tandy's application and system software—including the "needlessly complex" TRSDOS—and high cost of its peripherals. He reported, however, that with the Omikron board, additional memory, and 8- and 5 1/4-inch disk drives, "for a total cost of under $5000, you have a 48 K-byte machine capable of running all the TRS-80 programs, CP/M software, and top-grade text editors like Word Master, Magic Wand, Electric Pencil, and the Proteus editor ... all without building a single kit".[67]

Three years later Pournelle was less positive about the computer. He wrote in May 1983, "As to our TRS-80 Model I, we trashed that sucker long ago. It was always unreliable, and repeated trips to the local Radio Shack outlet didn't help. The problem was that Tandy cut corners".[68] Pournelle wrote in July:[57]

I'm a little bitter about my experiences with Tandy. I had genuinely thought that the Model I was the machine of the future: an inexpensive home computer that could be expanded by stages until it would do professional work. Of course it was never that. First, Tandy tried to fence in Model I users through that goofy operating system, and then it wouldn't let Radio Shack stores sell non-Tandy software. ... It had never been all that well designed, and when sales took off much faster than anticipated, the quality control system couldn't cope.

Compatible successors

Tandy would go on to replace the Model I with the broadly compatible Model III in 1980. (The TRS-80 Model II had been an entirely different and incompatible design). The Model III was in turn succeeded by the backward-compatible Model 4 in 1983.

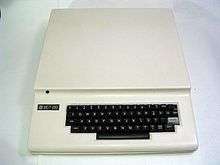

Model III

Tandy released the TRS-80 Model III on July 26, 1980. The improvements of the Model III over the Model I included:[69] built-in lowercase, a better keyboard with repeating keys, an enhanced character set, a real-time clock, 1500-baud cassette interface, a faster (2.03 MHz) Z-80 processor, and elimination of the cable spaghetti (due to its all-in-one enclosure). Furthermore, a Model III with two floppy drives required the use of only one electrical outlet (a two-drive Model I required five outlets: one each for the CPU/keyboard, Expansion Interface, Video Monitor, and the drives) and avoided the complicated power on/off sequence of the Model I. Shortly after the Model III's introduction, Model I production was discontinued as it did not comply with new FCC regulations as of January 1, 1981 regarding electromagnetic interference.[20][35][70][6]

Tandy distinguished between the high-end Model II[15] and Model III, describing the latter as "an administrative system, good for things like word processing, data management and VisiCalc operations" and suitable for small businesses.[71] The lowest-priced version of the Model III was sold with 4KB of RAM and cassette storage. The computer's CPU board had three banks of sockets (8 sockets to a bank) which could accept type 4116 DRAMs, so memory configurations came in 16KB, 32KB, or 48KB RAM memory sizes. Installations with 32k or 48k of RAM could be upgraded with floppy disk drive storage. There was space inside the computer cabinet for two full-height drives. Those offered by Tandy/Radio Shack were single-sided, 40 track, double-density (MFM encoding) for 180k of storage. Third-party suppliers offered double-sided and 80-track drives, though to control them they had to modify the TRSDOS driver code or else furnish an alternative third-party DOS which could (see below). The installation of floppy disk drives also required the computer's power supply to be upgraded. There was no internal cooling fan in the Model III; it used passive convection cooling (unless an unusual number of power-hungry expansions were installed internally, such as a hard disk drive, graphics board, speedup kit, RS-232 board, etc.).

Tandy claimed that the Model III was compatible with 80% of Model I software.[71] The Model III's memory map and system architecture was mostly the same as the Model I, but the disk drives and printer port were moved from memory mapped to port I/O, thus Model I software that attempts to manipulate the disk controller directly or output to the printer (in particular Model I DOSes and application packages such as Visicalc and Scripsit) will not work. Under the supplied TRSDOS 1.3 operating system Model I disks could be read in the Model III, but not vice versa.[20] The optional LDOS OS (by Logical Systems Inc.) used a common disk format for both Model I and Model III versions. Customers and developers complained of bugs in the Model III's Microsoft BASIC interpreter and TRSDOS.[71] Tandy/Radio Shack (and TRS-80 magazines like 80 Micro) periodically published a great many software patches to correct these deficiencies and to permit users to customize the software to their preferences.

Differences in the WD1771 and WD1791 floppy controllers created problems reading Model I disks on a Model III (the double density upgrade in the Model I included both chips while a Model III had only the WD1791). The WD1771 could support four data markers while the WD1791 only supported two, and some versions of TRS-DOS for the Model I also made use of them. In addition, they were used by copy protection schemes. Software was available to allow Model I disks to be read on a Model III.

The WD1791 could support the 500 bit/s bitrate needed for high density floppy drives, but the controller was not capable of using them without extensive modifications.

TRS-DOS for the Model III was developed in-house by Radio Shack rather than being contracted out like the Model I's DOS. None of the code base from Model I DOS was reused and the Model III DOS was rewritten from scratch; this also created some compatibility issues since the Model III DOS's API was not entirely identical to the Model I DOS. This was primarily to avoid legal disputes with Randy Cook over ownership of the code as had occurred with Model I DOS and also because Radio Shack originally planned to include several features in the Model III such as 80 column text support that ended up not materializing. Two early versions, 1.1 and 1.2, were replaced by version 1.3 in 1981 which became the standard Model III OS. TRS-DOS 1.3 was not format compatible with 1.1 and 1.2; a utility called XFERSYS was provided which converted older format disks to TRS-DOS 1.3 format (this change was permanent and the resultant disks could not be read with the older DOS versions).

The Model III's boot screen was cleaned up from the Model I. Instead of displaying garbage on screen at power up, it displayed a "Diskette?" prompt if a bootable floppy was not detected. The user could then insert a disk and press any key to boot or Break-Reset to go into BASIC.

While Model I DOS was fairly flexible in its capabilities, Model III DOS was hard coded to only support 180k single sided floppies, a problem fixed by the many third party DOSes. To that end, when Radio Shack introduced hard disks for the TRS-80 line in 1982, they chose to license LDOS rather than attempt to modify Model III DOS for hard disk support.

BASIC on the Model III was 16k in size and incorporated a few features from Level I Disk BASIC

DOS 1.3 was given a few more minor updates, the last being in 1984, although the version number was unchanged. This included at least one update that would write an Easter Egg message "Joe, you rummy buzzard" on an unused disk sector, which was reputedly a joke message left by a programmer in a beta version, but accidentally included in the production master.[72]

The Model III keyboard lacked a CONTROL key. Many application programs used the so-called "at key" (the key with a commercial at symbol), while others used the key combination SHIFT-up arrow. Often the CLEAR key was used in combination with number and alpha keys. The Model III keyboard also lacked a CAPS key; to caps-lock the alpha keys the user pressed the key combination SHIFT-zero. Under LDOS typeahead was supported.

Aftermarket hardware were offered by Tandy/Radio Shack and many third-party manufacturers. The usual selection of add-ons and peripherals available for the Model I were offered: outboard floppy drives (two additional drives could be connected to a card-edge connector on the back panel), an outboard hard disk drive (LDOS was furnished as Tandy's hard drive OS vice TRSDOS), a high-resolution graphics board[73] (resolution 512x192 pixels), an RS-232C serial port on an internal circuit card, and a parallel printer (connected by a card-edge connector). A particularly popular hardware/software add-on was the Orchestra-90[74][75] music synthesizer. It could be programmed to play up to five voices with a range of six octaves stereophonically. A great many Orch-90 (as it was often called) music files were available for download from Compuserve. The Orch-90 was licensed from a company called Software Affair, which also produced the Model I-compatible Orchestra-85 from 1981.

Because TRSDOS 1.3 was found wanting by many users, Tandy offered (at additional cost) Logical System's LDOS Version 5 as an alternative. As with the Model I, other third-party sources also offered TRSDOS alternatives for the Model III, including Apparat's NEWDOS, Alphabit's MultiDOS, and Micro Systems Software's DOSPlus. These were compatible with TRSDOS 1.3 and ran the same applications programs, but offered improved command structures, more and better system utilities, and enhancements to the Microsoft BASIC interpreter. After writing the original Model I TRS-DOS, Randy Cook began work on his own DOS, titled VTOS, which was soon superseded by LDOS and also created some frustration for users as it was the only TRS-80 DOS to be copy protected.

Although mostly intended as a disk-based computer, the Model III was available in a base cassette configuration with no disk hardware and only 16k of RAM. Radio Shack also offered a Level I version with 4k or 16k, otherwise identical to Model I Level I BASIC, but with the addition of LPRINT and LLIST commands for printer output. Upgrading to a disk machine necessitated installing at least 32k of RAM, the disk controller board, and an additional power supply used for the disk drives.

As with the Model I's EI, the RS-232 port on the Model III was an extra cost option and not included in the base price of the computer.

Like the Model I, the Model III sold very well in the educational market. Many school administrators valued the Model III's all-in-one hardware design because it made it more difficult for students to "walk away with" components of the computer when the all-too-busy teachers weren't looking. InfoWorld approved of the Model III's single-unit design, simplified cable management, and improvements such as lack of keyboard bounce and improved disk reliability. The reviewer, a former Model I owner, stated "I'm impressed" and that "had the Model III been available, it's probable that I wouldn't have sold it". He concluded, "If you're looking for a computer that's not too expensive but that performs well, you would be wise to test the Model III—you might end up buying it."[35]

Don French, who had left Radio Shack to found FMG Software after designing the Model I, expressed his disappointment in the new machine while trying to convert CP/M to run on it. "I've encountered numerous problems with the floppy drive and its interface. Radio Shack will sell a Model III to anyone. They're trying to market it as a business computer when the existing software is woefully inadequate. 48k just isn't enough. You run out of memory before you get going. They're selling a medical package that takes up nine disks. I think the Model III is a very poorly conceived machine."[76]

Model 4

.jpg)

The successor to the Model III was the TRS-80 Model 4 (April 1983, with "4" written as an Arabic numeral). It had faster Z80A 4 MHz CPU,[77] a larger video display 80 columns x 24 rows, bigger keyboard, and could be upgraded to 128KB of RAM. The Model 4 was fully compatible with Model III software and industry-standard CP/M applications software. A diskless Model 4 (with 16KB RAM) cost $999, with 64KB RAM and one single-sided 180K disk drive $1699, and two drives $1999; an upgrade for Model III owners cost $799 and provided a new motherboard and keyboard.[52] Tandy sold 71,000 in 1984.[78] The new computer used exactly the same all-in-one cabinet as the Model III, adopting a more contemporary-looking beige color scheme instead of the 1970s-style "Star Wars" black and gray used on the Model I/III. The Model 4's case also switched from spray-painted translucent plastic to molded plastic, ensuring that the coloring was permanent and not prone to peeling off.

The Model 4's first appearance in the Radio Shack catalog read as follows: "Yes, it looks like a Model III, but it's much much more. Compare the price and features of our amazing new Model 4 to any other computer in its class. You'll find that for power, versatility, and convenience it is a true breakthrough. To add the same features to other computers, you'd have to pay a whole lot more."[79]

Running CP/M on the Models I/III had only been possible via a hardware modification that remapped the BASIC ROMs away from memory address zero, such as the third-party add-on sold as the Omikron Mapper board, or by running a version of CP/M modified to run at a starting address other than zero. However, this also required modified applications, since the area of memory at zero contained the vectors for applications to access CP/M itself. The Model 4 could run CP/M without modification. Digital Research produced for Tandy/Radio Shack a version of its CP/M 3.0 for the Model 4,[80] but it was buggy and actually provided a smaller Transient Program Area than the non-banked CP/M 2.2. A third party, Montezuma Micro, supplied a version of CP/M 2.2 that was customized for the Model 4's hardware and had a utility for reading/writing CP/M disk formats of many other brands of computer. A Borland Sidekick-like utility (Monte's Window) was sold separately that ran in the 64KB of banked RAM.

The Model 4 used WD1770/1773 floppy controllers in place of the WD1791 which allowed for a larger gap between the index hole and first sector; later releases of TRS-DOS and LDOS were modified to be able format using this setup.

The Model 4 shipped with TRSDOS 6, an enhanced version of the popular LDOS (itself an enhancement to older versions of TRSDOS) by Logical Systems. When the Model 4 boots into TRSDOS 6 the video display switches into 80×24 mode and the entire 64KB address space is mapped as RAM. The Model 4 is also capable of running all Model III software when a Model III operating system disk is detected and loaded during bootup, with a 64×16 video mode and Model III ROMs mapped from address zero. Model 4 features, including the internal speaker, are unavailable in Model III mode.[52] Users experienced in Z-80 assembler could access Model 4 features like the larger screen and banked RAM in Model III mode through its machine I/O ports.

TRSDOS 6 provided a host of utilities and filters to make the most of the Model 4's new hardware features. Its ramdisk program was called Memdisk and could use the optional extra 64KB of ram, or a specified portion of the Z-80's main 64KB. This could hold TRSDOS's most-often needed modules and utilities with about 30KB to spare, freeing all floppy drives for data diskettes. Installing the system on the Memdisk also speeded the computer's operation greatly, as system overlays would load from memory rather than from disk. TRSDOS also offered a SYSRES command which made specified TRSDOS overlay modules resident in the main 64KB, permitting more free disk space on the system diskette in drive zero, which also enhanced the free space available on a system Memdisk. TRSDOS also provided a print spooler that ran as a background task while other applications were in use; it could take little user memory in an expanded machine since it could use the extra 64KB as its buffer memory. The BACKUP utility was versatile, if somewhat confusing for beginners due to its many parameters. A FORMS filter made tailored printouts possible for applications lacking capability for formatted printing. A keyboard filter, Keystroke Multiplier, let the user define macro strings to the <clear><alpha> keys. A barebones (non-symbolic) machine language debugger was standard. TRSDOS had an @DEBUG SVC available, which a programmer could insert into a program to invoke the debugger on command. Job Control Language served as the equivalent to MSDOS's batch processor. A capable terminal program, COMM/CMD, serviced the RS-232 serial port.

A new version of BASIC was included with the Model 4 that used a more recent iteration of Microsoft BASIC with support for variable names longer than two characters, WHILE...WEND loop structures, and other features. Some features from the Model III BASIC were dropped such as the ability to "crunch" BASIC statements by omitting spaces (this feature, also found in Commodore BASIC, was designed to reduce the memory footprint of programs). It also lacked the commands for setting, resetting, and testing graphics blocks on the display.

For veteran Model III BASIC programmers Model 4 BASIC came with two disadvantages. First, variable names had to be separated from BASIC keywords with spaces, unlike Model III Disk BASIC which permitted them to be run together. This is because the Model 4 interpreter's variable names could be up to 40 characters in length, and the Model III interpreter's variable names had to be one or two characters in length (the interpreter would accept longer names but only the first two characters were significant for uniquely identifying the variable). The Model 4 version of BASIC therefore had to search for the delimiting space to find the end of the variable name. What this meant for the programmer converting his old Model III program into Model 4 BASIC was a great deal of tedious editing because Model III programmers, to save memory and speed execution, typically compacted their code by using two-character variable names and eliminating spaces separating variables and keywords. The second disadvantage was that Model 4 BASIC lacked the command available in Model III BASIC for sorting arrays (CMD"O"). This was a major headache for programmers maintaining code for business applications, and prompted many BASIC coders to homebrew a replacement capability. Later third-party software publishers made products available to fill the gap for non-programmers. Another solution preferred by some was to continue running their programs in Model III mode under Model III BASIC, but activating the Model 4's faster speed, larger video display, and extra keys by manipulating its hardware with machine code. For those programming in languages other than interpreted BASIC, but never updated for the Model 4, this was their only option for accessing the new Model 4 features (Microsoft eventually updated their entire line of language products for the Model 4).

One notable program available only for the Model 4 was marketed by Radio Shack as DoubleDuty.[81] This was one of the very first task-switching programs available for any microcomputer. It used the upper 64KB of a 128KB machine to keep resident a second TRSDOS application, which could be switched instantly with another application loaded into the main 64KB. A third partition was available for TRSDOS library commands, such as DIR. DoubleDuty first appeared in Radio Shack's 1985 Computer Catalog (RSC-12), the same year that IBM's Topview, Apple's Switcher, and Quarterdeck's DESQview first became available. DoubleDuty was written by Randy Cook, the author of the first version of TRSDOS for the original Model I.

The Model 4's memory mapping and OS more closely resembled the TRS-80 Model II than it did the Model III. Like the Model II, there was no ROM-based OS and all OS software was RAM-resident and loaded from disk at bootup. There was only a small boot loader ROM which would check for the presence of a Model 4 OS disk and if one was not detected, it would default to Model III mode. Also like the Model II, the OS used vectored API calls instead of absolute addresses, and software developers were encouraged to use the API calls rather than low-level hardware access to ensure compatibility with any future iterations of DOS and the BIOS ROMs.

Interfacing with the computer's hardware was likewise done differently than previously had been usual practice. Rather than accessing the memory-mapped keyboard and video directly, this was done entirely through the TRSDOS SVCs. This method permitted I/O redirection over all the computer's devices, including the disk drives, and made possible, for example, to "print" a document to a disk file so it could be printed at a later time when a printer was physically available. Another frequent use of I/O redirection was redirecting video output to the printer for permanent hardcopy of a program run. TRSDOS supplied the LINK, ROUTE, and FILTER commands to enable these capabilities. This method also ensured consistent communication between memory resident modules attached to the OS's logical devices. Some applications programmers, however, did circumvent this device-independent approach by physically accessing the computer hardware. The most glaring example of this was Radio Shack itself when it produced its SuperScripsit word processor; their programmers insisted on having the infamous CTL255 routine built into the keyboard driver expressly for this purpose. Another offender was Anitek Software's Lescript. These two applications would ignore any filter programs attached to the keyboard device, depriving the user of some capable terminate-and-stay-resident programs, such as Misosys' Sidekick-like Pro-WAM Window Application Manager.

The disk drive storage on the Model 4 was identical to the Model III, consisting of one or two single-sided full-height 5.25" drives (various brands of disk drive were used in the Model 4, while the Model III had exclusively Tandons), providing 180k of storage with TRS-DOS. An additional two drives could connected via the external floppy port. Any floppy drive with the Shugart-style 34-pin interface could be used, thus it was possible to upgrade a Model 4 to use double-sided, 80 track, or even 3.5" floppies. In addition, external hard disks were available. A parallel printer could be added using another card-edge connector provided for this purpose. An RS-232 serial port was optional on the original versions of the Model 4.

The keyboard had a control key, a Caps Lock key, and three function keys. The video display can be dumped to the printer by pressing SHIFT-colon. CONTROL-R will repeat the last command. TRSDOS supported a typeahead feature with an 80 character key buffer. It used the TRSDOS event tasker, so operations that disable Z80 interrupts (such as floppy disk access) could result in missed keystrokes.

The video display RAM was not memory-mapped as it had been on the previous Models I and III. Rather, whenever a program called functions requiring video RAM to be modified, TRSDOS executed code that switched the 2KB bank of video RAM into Z80 address space (the uppermost 2KB of hexadecimal F400 – FFFF). The keyboard matrix and typeahead buffer also occupied this address range (the lowermost 1KB). While this freed 1920 bytes of Z80 address space for programs, it was marginally slower than writing directly into video RAM. The video hardware supported characters in reverse video and Model I/III style block graphics. Due to the different screen resolution (640x240 pixels rather than 512x192 pixels), the block graphics characters were not of uniform height. The ten vertical pixels in each character cell were divided into three graphic blocks, the upper two of which were four pixels high, and the bottom graphics block took the remaining two vertical pixels. Because the graphic blocks were not of uniform height, this made video games in Model 4 mode somewhat unattractive; game programmers preferred running games in Model III mode. A 40 character wide display mode was available using a double-width raster image. By manipulating the video hardware in machine code, the Model III video modes (64 and 32 character columns with 16 rows) were available as well. An alternate character set was available which included the entire Greek alphabet and special symbols.

As with the Model III, the Model 4 was available in a baseline model with no disk drives and only 16k. They used a 16kx1 DRAM known as the 8040517. This chip, also used in 16k TRS-80 CoCo 2s, is functionally identical to a 4116 DRAM, but only uses +5V power instead of the 4116's tri-voltage power. 64k and 128k models used standard 4164 DRAMs. Unlike previous machines, the RS-232 port was standard equipment and no longer an extra cost option. The RS-232 and printer ports were also moved to the back instead of the underside of the computer, making them more easily accessible.

The Model 4 was announced in the same press release (April 1983) as was the TRS-80 Model 100 laptop. The two computers were often marketed by Tandy/Radio Shack as a complementary pair. Model 100 cassette tapes were readable on the Model 4 with its cassette interface and a TRSDOS 6 utility called TAPE100/CMD, which stored Model 100 programs and data as TRSDOS disk files. Programs and files could also be transferred back and forth via an RS-232 serial cable. Both the Model 4 and the Model 100 came with terminal software as a built-in feature.

The Model 4 has the ability to display 640×240 or 512×192 high-resolution monochrome graphics with an optional board which attaches to a socket connector on the logic board. The Radio Shack Model 4 graphics board retailed for $249 and included a modified version of Microsoft BASIC (called BasicG) with commands for drawing basic geometric shapes and manipulating arrays in graphics RAM. The graphics screen memory was separate from the usual character screen, and the two could be displayed together or separately. A third-party company called Micro Labs based in Richardson, Texas sold a compatible graphics board which was popular because it was sold for only $199 (initially). It came with a different BASIC providing for graphics commands called GBasic. Whereas the Radio Shack board had 32KB of graphics RAM, the Micro Labs board had 20KB. Since only 19,200 bytes are required to render a 640 x 240 pixel screen, the additional RAM on the Radio Shack board was available for windowing the viewable screen around a larger virtual area. The graphics RAM was accessible through four Z-80 I/O ports and was especially easy to access for uses other than graphics. For example, there was a public domain utility called Grafdisk that added the graphics memory to regular banked memory to create a larger TRSDOS ramdisk (96K on the Radio Shack board).

Early versions of the Model 4 mainboard were designed to accept a Zilog Z800 16 bit CPU upgrade board to replace the Z80 8 bit CPU but this option was never released. In 1987 a company called H.I. Tech produced an enhanced CPU board, the XLR8er, using the Hitachi HD64180 Z-80 compatible processor. It ran with a 6.144 megahertz clock rate and added 256K of memory that could be used as a RAM disk. When combined with the upper 64K of Model 4 banked RAM, a ramdisk of up to 384K could be mounted. Later, software was developed that could access XLR8er RAM as standard TRSDOS 32K banks through the @BANK supervisor call. This made the extra memory accessible to standard TRSDOS applications coded to use banked RAM. The Hitachi CPU also executed many Z-80 instructions in fewer clock cycles than the Zilog chip; 8Mhz performance was claimed but in reality most software realized a performance improvement of only 25 to 30 percent. Exceptions were programs that made heavy use of the Z-80 block instructions like LDIR and CPIR. This group of instructions take 21 transition states per iteration to execute on a Z-80; on the HD64180 they take only 14. These sorts of programs realized an effective clock speed of 7 megahertz (75% speedup) with the XLR8er board. There were enthusiast created programs that could access the 64180's DMA channels to attain an even higher rate of data transfer.

The Model 4 included a sound generator, a first for the TRS-80 line as the Model I/III required the user to output sounds to the cassette port, which would be then connected to a stereo amplifier for sound output. However, its sound capabilities were extremely limited, with just seven tones that could be produced, ranging from C to G♭ on the musical scale, and there was no E. Each tone had 32 different durations it could be sounded for. One Radio Shack spokesman described the Model 4's sound generator as "being intended for business alerts".

BYTE in October 1983 noted the lack of native software for the Model 4 but praised its backwards compatibility and TRSDOS 6's new features. The magazine concluded that the Model 4 "provides a lot of flexible computing power ... Radio Shack has a guaranteed winner".[52]

Gate Array Model 4

The original version of the Model 4 (Radio Shack catalog number 26-1069) did not use gate array logic chips on its CPU board, but rather Programmable Array Logic chips (PALs). Starting from late 1984, a revised version was produced which came to be known as the Gate Array Model 4 (catalog number 26-1069A). This change greatly reduced the chip count and allowed the circuitry for the Floppy Disk Controller and the RS-232 serial port to be included on the CPU board (making this new Model 4 a single-board computer, unlike the original 26-1069). The upgrade to 128K did not require the special PAL chip available only from Radio Shack, allowing users to expand the memory themselves with third-party RAM chips. The Gate Array machine shipped with a green video screen instead of the black-and-white screen, and the arrow keys on the keyboard were grouped together into a single cluster (the old Model 4 had two arrows on each side). Veteran TRS-80 game players were quite unhappy with the new arrangement of arrow keys.

An improvement was made in the computer's speed of execution. The original Model 4, though advertised as a 4 MHz machine, actually performed at an effective speed of 3.5 MHz because wait states were inserted for the slower PAL support circuitry. The Gate Array CPU board allowed the Tandy engineers to clock the Z-80 at an actual 4 MHz clock rate without any wait states. This difference in operating speed made many third-party hardware modifications, particularly speedup kits, rather troublesome to install on the older Model 4s extant.

Model 4P

A "luggable" version known as the Model 4P (September 1983, Radio Shack catalog number 26-1080) is a self-contained unit with a case design similar to that of a portable sewing machine. It had all the features of the desktop Model 4 except for the ability to add two outboard floppy disk drives and the interface for cassette tape storage (audio sent to the cassette port in Model III mode are sent to the internal speaker). It was sold only with the two internal single-sided 180KB drives. It was later made with the Gate Array technology (catalog number 26-1080A). The TRS-80 magazine 80 Micro published an article describing a simple motherboard modification to enable the installation of two external floppy drives.

The 4P's CPU board lacked the Model III ROM chips containing the Model III Microsoft BASIC interpreter. Instead the computer was furnished with a floppy disk labelled "Model III/A". This was called the "Model III ROM Image" disk. If the operator wanted to boot a Model III DOS, he inserted this disk into the boot drive after powering up. Once it was loaded, he replaced the ROM Image disk with his Model III DOS boot disk and pressed reset. From then on the computer would behave exactly like a Model III.

The 4P had a slot for an internal modem board. The Radio Shack modem board used its own proprietary command set and only supported communications at 300 baud. Later a third-party company called Teletrends produced a 1200 baud modem board that used the industry-standard Hayes AT command set.

It had an internal fan; its compact design did not permit it to use passive convection cooling as did the desktop Model 4.

A notable aspect of the 4P's video display was the solid, fully formed appearance of its text characters. This resulted from the fact that its 9-inch screen had the same 640x240 resolution as the desktop's 12-inch screen, producing a greater density of pixels.

Tandy discontinued the 4P by spring 1985, stating that "even though you won't find a more enthusiastic and devoted group of owners than our Model 4P folks, transportables just weren't moving well for any company that also sold a desktop version".[63]. The best-selling transportables at this time were those of the Kaypro line by Non-Linear Systems, which ran the popular CP/M OS and bundled the MicroPro line of applications including the bestselling Wordstar.

Model 4D

Tandy's first MS-DOS computer was the Tandy 2000 in 1983. By 1985 it also sold the popular 1000. The company stated that year that although Tandy had discontinued the 4P and other Model 4 variants, it intended to produce the computer "until the marketplace tells us it is no longer a product" and promised "a new double-sided drive version this fall".[63] Tandy also had outstanding contracts with public school districts throughout the US for continued support of the TRS-80s in classroom use.

The final version of the Model 4 was the Model 4D (Radio Shack catalog number 26-1070) in 1985. It was a Gate Array desktop machine featuring dual TEC-branded (not TEAC) FB-503 disk drives[82] with a capacity of 360KB each (40 track, double-sided). Rather than using a lever-style latch as had previous Model 4 drives (various brands were used throughout its production run), the new drives used a twist-style latch that provided for more reliable clamping. They were actually half-height drives mounted with full-height faceplates. These drives could actually format 42 tracks (or cylinders) with no difficulty, though this was unadvertised and not officially approved by Tandy or Logical Systems. This technique upped the available storage on each disk to 378KB. To create such a floppy disk, the user needed to specify the (CYL=42) parameter on the command line when invoking the FORMAT utility.

The Deskmate productivity suite was bundled with the 4D. It supplied simple applications including a word processor, filer, spreadsheet, calendar, and mail manager.

Model 4Ds sold during 1987 and later shipped with an updated version of its operating system, now called LS-DOS 6.3 after its third-party developer Logical Systems. It provided scores of enhanced features, the most important of which was the ability to handle file dates through December 31, 2011. The original TRSDOS 6 licensed to Radio Shack could only handle dates through December 31, 1987. Files were now time-stamped as well. Another useful feature modified the BASIC interpreter to access LS-DOS Supervisor Calls using integer variables, without having to resort to high memory subroutines coded in Z-80 assembler. Basic commands like LIST, EDIT, and PRINT were accessible via single keystrokes. Also welcome in LS-DOS 6.3 was the TED/CMD simple text editor. The TRSDOS non-interactive BUILD command had previously been the only method of creating plain text files. TED's chief virtue was that it occupied only 3KB of disk space while offering decent cursor movement and block capabilities. This is no small convenience for a system with only floppy disk storage.

The Model 4D was the last computer descended from Radio Shack's original Model I from 1977. It was not branded as a Radio Shack product, however. The badge mounted on its front cover branded it as the "Tandy TRS-80 Model 4D". This change in marketing resulted from Tandy corporation's desire to enhance its stature in the marketplace, because it was perceived by some in the computer press that the old "Radio Shack" moniker connoted an image of inferior quality. The Model 4D would be the last computer to bear the "TRS-80" name. It retailed for $1199 at its introduction in 1985. During 1987–1988 the retail stores removed the Model 4Ds from display but they were kept in the yearly computer catalog and were available by special order through 1991, when they were at last closed out for $599. Parts and repair service remained available for several years longer.

Clones

Many clones of the TRS-80 Model I came on the market: the Lobo Max-80 (Lobo also produced their own version of the Expansion Interface), the LNW-80 Models I/II and Team computers (LNW also produced an alternate version of the Expansion Interface), and the Dutch Aster CT-80, a computer that could run both TRS-80 and CP/M software, and also had all the improvements of the later Model III.[83]

EACA in Hong Kong made a Model I clone that was marketed around the world under different names with modifications. In Australia and New Zealand it was the Dick Smith System 80, in North America it was PMC-80 and PMC-81, in Hungary the HT-1080Z, in South Africa the TRZ-80, and in Western Europe it was Video Genie. The expansion bus was different and EACA also made its own Expansion Interface to fit it. There were several versions, and it was later split into a 'home' and a 'business' version, Genie I and II, and System-80 Mark I and II, where the II would have a numeric keypad instead of the built-in cassette player. EACA's Colour Genie was also based on TRS-80 Model I but with improved graphics and other changes, reducing its compatibility.[83]