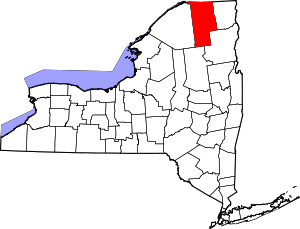

St. Regis Mohawk Reservation

Coordinates: 44°58′26″N 74°39′49″W / 44.973972°N 74.663590°W

St. Regis Mohawk Reservation is a Mohawk Indian reservation in Franklin County, New York, United States. It is also known by its Mohawk name, Akwesasne. The population was 3,288 at the 2010 census.[2] The reservation is adjacent to the Akwesasne reserve in Ontario and Quebec. The Mohawk consider the entire community to be one unit, and have the right to travel freely across the international border. The reservation contains the community of St. Regis and borders the community of Hogansburg in the town of Bombay.[3]

Under the terms of the Jay Treaty (1794), the Mohawk people may pass freely across the Canada–United States border. The two parts of the reservation are separated by the St. Lawrence River and the 45th parallel.

The Mohawk are one of the original Five Nations of the Iroquois, historically based in present-day New York. They were located chiefly in the Mohawk Valley and were known as the "Keepers of the Eastern Door", prepared to defend the Iroquoian territory against other tribes located to the east of the Hudson River.

The St. Regis Reservation adopted gambling in the 1980s. It has generated deep controversy. Broadly speaking, the elected chiefs and the Mohawk Warrior Society have supported gambling, while the traditional chiefs have opposed it. Today, the reservation is home to the Akwesasne Mohawk Casino.

The elected tribal governments on the New York and Canadian sides and the traditional chiefs of Akwesasne often work together as a "Tri-Council" concerning areas of shared interest, for example to negotiate land claims settlements with their respective national government.

The Mohawk Nation views the reservation as a sovereign nation. It shares jurisdiction with the state of New York and the United States.

Geography

The reservation is at the international border of Canada and the United States along the St. Lawrence River.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the Indian reservation has a total area of 21.0 square miles (54.4 km2). 19.0 square miles (49.1 km2) of it is land, and 2.0 square miles (5.3 km2) of it (9.76%) is water.[2] It is bordered by the New York towns of Fort Covington (east), Bombay (south), Brasher (southwest), and Massena (west), and by the Akwesasne Indian Reserve to the north in the Canadian provinces of Quebec and Ontario. The nearest city is Cornwall, Ontario, which lies 6 miles (10 km) to the northwest, across the Akwesasne Reserve.

History

The original settlement was known as Akwesasne, called Saint Régis by French Jesuit missionaries, presumably after Jean François Régis, the martyred priest and canonized as a Catholic saint in 1737. It was founded about 1755 by several Catholic Iroquois families, primarily Mohawk, from the mission village of Caughnawaga, Quebec (now known as Kahnawake). They were seeking better lives for their families, as they were concerned about negative influences of traders at Caughnawaga, where some Mohawk became debilitated by alcohol. The Mohawk were accompanied by Jesuit missionaries from Caughnawaga.[4]

After the United States acquired this territory in settlement of its northern border, relations among the people and the varying jurisdictions became more complex. But by the 1795 Jay Treaty, the Mohawk retained the right to travel freely over the border. The Mohawk on both sides of the St. Lawrence River have lost land and been adversely affected by major infrastructure projects conducted by state and federal authorities; for instance, the St. Lawrence Seaway, what is now known as the Three Nations Crossing bridge, and dams on the rivers for power projects.

Since 1762, mills and dams were built by private, non-Native interests on the St. Regis River at what developed as the village of Hogansburg, now within the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation. In 1929 Erie Boulevard Hydropower built an 11-foot-high dam at the site to generate hydroelectric power. It disrupted the annual salmon fish run from the St. Lawrence, depriving the citizens of the reservation of one of their staple foods, and adversely affecting the populations of salmon and other migratory fish. By 2010 the dam had been uneconomical and would have cost too much to upgrade, including providing for fish passage. The owner gave up their federal license.[5]

The St. Regis Reservation applied to FERC take over and dismantle the dam, which they did in 2016. Based on restoration of fisheries after such dam removals in other locations across the country, they expect salmon and other migratory fish, such as walleye, to return to the region: 275 miles of the St. Regis River has been reopened to migratory fish that spend part of their lives in the Atlantic Ocean.[5]

In 2013 the tribe received a $19 million settlement from "GM, Alcoa, and Reynolds for pollution of tribal fishing and hunting grounds along the St. Lawrence River".[5] The companies have undertaken cleanup of the pollution. The tribe intends to use this money to redevelop the former dam site as "the focus of a cultural restoration program that will pair tribal elders with younger members of the tribe to restore the Mohawk language and pass on traditional practices such as fishing, hunting, basket weaving, horticulture and medicine, to name a few."[5]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1900 | 1,253 | — | |

| 1910 | 1,249 | −0.3% | |

| 1920 | 1,016 | −18.7% | |

| 1930 | 945 | −7.0% | |

| 1940 | 1,262 | 33.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,409 | 11.6% | |

| 1960 | 1,774 | 25.9% | |

| 1970 | 1,536 | −13.4% | |

| 1980 | 1,802 | 17.3% | |

| 1990 | 1,978 | 9.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,699 | 36.5% | |

| 2010 | 3,228 | 19.6% | |

| Est. 2014 | 3,248 | [6] | 0.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[7] | |||

As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 2,699 people, 904 households, and 668 families residing in the Indian reservation within the US boundary. The population density was 142.2/mi² (54.9/km²). There were 977 housing units at an average density of 51.5/mi² (19.9/km²). The racial makeup of the Indian reservation was 97.41% Native American, 2.07% White, 0.07% from other races, and 0.44% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.74% of the population.

There were 904 households out of which 44.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.9% were married couples living together, 23.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.0% were non-families. 22.9% of all households were made up of individuals and 6.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.97 and the average family size was 3.44.

In the Indian reservation, the population was spread out with 34.1% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to 44, 18.1% from 45 to 64, and 7.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 96.2 males.

The median income for a household in the Indian reservation was $32,664, and the median income for a family was $34,336. Males had a median income of $27,742 versus $21,774 for females. The per capita income for the Indian reservation was $12,017. About 19.4% of families and 22.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.3% of those under age 18 and 14.9% of those age 65 or over.

Controversies

Drug and human smuggling

Because of the latitude of this area, rivers freeze in winter, providing shortcuts for the Mohawk crossing the international border. This situation also makes the border more porous for smugglers of many items, including liquor, cigarettes, drugs and persons.[9] The New York Times covered this issue in February 2006 in an article headlined "Drug Traffickers Find Haven in Shadows of Indian Country".[10]

The Akwesasne police and government spokespersons have defended their work, saying they have had to take on an unfair federal burden of border enforcement while not receiving additional funding. Due to a quirk in the law, they were not eligible to receive grants from the Department of Homeland Security that were available to local jurisdictions. The chief of the Akwesasne Mohawk police noted that drug smuggling was a problem that extended along the Canadian-US border and was not limited to Akwesasne. In March 2006, the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation was awarded a $263,000 grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs Office of Legal Services, in order to "fight drug use, violent crime, and drug and human smuggling."[9]

Collection of state sales tax

New York state has threatened to collect sales tax from sales of gasoline and cigarettes on Native American reservations but has not done so. The legislature often passes such a resolution[11] but the federally recognized tribe says that it has sovereign authority on its reservation and does not need to collect the state tax. New York citizens fail to report their applicable use taxes; this has become a problem both here and at areas surrounding other Indian reservations across New York. Merchants near the reservations complain that the tax-free sales constitute an unfair advantage for Native American-owned businesses. People on the reservation tend to respond that this is the only advantage they have, after years of discrimination and being dispossessed of their land.[12]

While the government officials argue, a Zogby poll commissioned in 2006 by the Seneca Nation of New York, allies of the Mohawk, showed that 79% of New York residents did not think sales taxes should be collected from reservation sales.[13]

In popular culture

- The reservation is the setting for the 2008 movie Frozen River. It depicts smuggling of illegal immigrants by Mohawk and associated Americans across the international border between Canada and the U.S. The film was shot in Plattsburgh, New York.

- The reservation was the setting for a Tom Swift children's book series (1910–1941).

Patent income

In 2017, the tribe entered into an agreement with Allergan Plc, under which Allergen transferred intellectual property rights to the drug Restasis to the tribe in an attempt to shield those patent rights from legal challenges. Allergan will pay the tribe $13.75 million, plus $15 million a year in annual revenues.[14]

See also

- You Are on Indian Land (1969, a documentary about a 1968 protest by the St. Regis Mohawk and Akwesasne.

References

- ↑ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 378.

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), St. Regis Mohawk Reservation, Franklin County, New York". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 2, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- ↑ Coit Gilman, Daniel; Thurston Peck, Harry; Moore Colby, c. 1904., Frank. The New International Encyclopedia. 15. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Karen Graham, "Hogansburg Hydroelectric Dam Taken Down by Native American Tribe", Digital Journal, 11 December 2016;accessed 20 January 2018

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Archived from the original on May 23, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 Shannon Burns (March 17, 2006). "BIA grant to help Akwesasne combat border drug smuggling". Indian Country Today. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ↑ Sarah Kershaw, "Drug Traffickers Find Haven in Shadows of Indian Country", New York Times, 19 February 2006; accessed 20 January 2018

- ↑ "Publication 750: A Guide to Sales Tax in New York State" (PDF). New York State Department of Taxation and Finance.

- ↑ Graham, Mike (April 25, 2006). "New York Company States American Indians Supporting International Terrorists". American Chronicle.

- ↑ Staba, David (March 21, 2006). "Analysis". Niagara Falls Reporter. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- ↑ Koons, Cynthia. "Casinos Aren't Enough as Native Tribe Makes Deal on Drug Patents".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Regis Mohawk Reservation. |

- St. Regis Mohawk Tribal website

- Tribal Constitution

- "Saint Regis Mohawk First Tribe Approved for Clean Air Plan", Environment News Service

- Akwesasne Cultural Center, Library and Museum

- Mohawk Casino

- Mohawk Bingo Palace and class II Casino

- Moore, Evan. "Gambling, murder split reservation/`It's nothing but a damn war zone," Houston Chronicle, 6 May 1990. A1.