Saint Maurice

| Saint Maurice | |

|---|---|

Saint Maurice by Matthias Grünewald c. 16th century | |

| Martyr | |

| Born |

3rd century Thebes, Egypt |

| Died |

287 Agaunum, Switzerland |

| Venerated in | |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation for the Causes of Saints |

| Major shrine | Abbey of St. Maurice, Agaunum (until 961), Magdeburg Cathedral (961-present) |

| Feast |

|

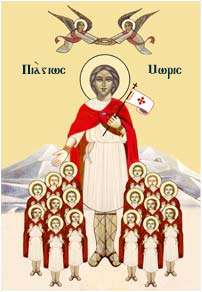

| Attributes | banner; soldier; soldier being executed with other soldiers, knight; indigenous African in full armour, bearing a standard and a palm; knight in armour with a red cross on his breast, which is the badge of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus |

| Patronage | alpine troops; Appenzell Innerrhoden;[1] armies; armorers; Burgundians; Carolingian dynasty;[1] Austria; clothmakers;[2] cramps; dyers; gout; House of Savoy;[1] infantrymen; Lombards; Merovingian dynasty;[1] Piedmont, Italy; Pontifical Swiss Guards; Saint-Maurice, Switzerland; St. Moritz;[1]Sardinia; soldiers; Stadtsulza, Germany; swordsmiths; weavers; Holy Roman Emperors |

Saint Maurice (also Moritz, Morris, or Mauritius; Coptic: Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲙⲱⲣⲓⲥ) was the leader of the legendary Roman Theban Legion in the 3rd century, and one of the favorite and most widely venerated saints of that group. He was the patron saint of several professions, locales, and kingdoms. He is also a highly revered saint in the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and other churches of Oriental Orthodoxy.

Early life

According to the hagiographical material, Maurice was an Egyptian, born in AD 250 in Thebes, an ancient city in Upper Egypt that was the capital of the New Kingdom of Egypt (1575-1069 BC). He was brought up in the region of Thebes (Luxor)

Career

Maurice became a soldier in the Roman army. He was gradually promoted until he became the commander of the Theban legion, thus approximately leading a thousand men. He was an acknowledged Christian at a time when early Christianity was considered to be a threat to the Roman Empire. Yet, he moved easily within the pagan society of his day.[3]

The legion, entirely composed of Christians, had been called from Thebes in Egypt to Gaul to assist Emperor Maximian to defeat a revolt by the bagaudae.[2] The Theban Legion was dispatched with orders to clear the Great St Bernard Pass across Mont Blanc. Before going into battle, they were instructed to offer sacrifices to the pagan gods and pay homage to the emperor. Maurice pledged his men’s military allegiance to Rome. He stated that service to God superseded all else. To engage in wanton slaughter was inconceivable to Christian soldiers he said. He and his men refused to worship Roman deities.[3]

Martyrdom

However, when Maximian ordered them to harass some local Christians, they refused. Ordering the unit to be punished, Maximian had every tenth soldier killed, a military punishment known as decimation. More orders followed, the men refused as encouraged by Maurice, and a second decimation was ordered. In response to the Theban Christians' refusal to attack fellow Christians, Maximian ordered all the remaining members of his legion to be executed. The place in Switzerland where this occurred, known as Agaunum, is now Saint-Maurice, Switzerland, site of the Abbey of St. Maurice.

So reads the earliest account of their martyrdom, contained in the public letter which Bishop Eucherius of Lyon (c. 434–450), addressed to his fellow bishop, Salvius. Alternative versions have the legion refusing Maximian's orders only after discovering innocent Christians had inhabited a town they had just destroyed, or that the emperor had them executed when they refused to sacrifice to the Roman gods.

Historicity

There is a difference of opinion among researchers as to whether or not the story of the Theban Legion is based on historical fact, and if so, to what extent. The legend, by Eucherius of Lyon, is classed by Bollandist Hippolyte Delehaye among the historical romances.[4] Donald F. O'Reilly, in Lost Legion Rediscovered, argues that evidence from coins, papyrus, and Roman army lists support the story of the Theban Legion.[5]

Denis Van Berchem, of the University of Geneva, proposed that Eucherius' presentation of the legend of the Theban legion was a literary production, not based on a local tradition.[6] The monastic accounts themselves do not specifically state that all the soldiers were collectively executed; an eleventh-century monk named Otto of Freising wrote that most of the legionaries escaped, and only some were executed.[7]

The military staunchly followed Isis or Mithras (Sol Invictus), until the time of Constantine the Great at the earliest, making it unlikely that Christians filled an entire legion. If the legend was a later fabrication by Eucherius, its dissemination served to draw pilgrims to the abbey at Agaunum.

Our Lady of Laus

Our Lady of Laus included an apparition of Saint Maurice, who appeared in an antique episcopal vestment and told Benoîte Rencurel that he was the one to whom the nearby chapel was dedicated, that he would fetch her some water (before drawing some water out of a well she had not seen), that she should go down to a certain valley to escape the local guard and see Mary, mother of Jesus, and that Mary was both in Heaven and could appear on Earth.[8]

Veneration

Saint Maurice became a patron saint of the German Holy Roman Emperors. In 926, Henry the Fowler (919–936), even ceded the present Swiss canton of Aargau to the abbey, in return for Maurice's lance, sword and spurs. The sword and spurs of Saint Maurice were part of the regalia used at coronations of the Austro-Hungarian emperors until 1916, and among the most important insignia of the imperial throne. In addition, some of the emperors were anointed before the Altar of Saint Maurice at St. Peter's Basilica.[1] In 929, Henry the Fowler held a royal court gathering (Reichsversammlung) at Magdeburg. At the same time the Mauritius Kloster in honor of Maurice was founded. In 961, Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, was building and enriching Magdeburg Cathedral, which he intended for his own tomb. To that end,

in the year 961 of the Incarnation and in the 25th year of his reign, in the presence of all of the nobility, on the vigil of Christmas, the body of St. Maurice was conveyed to him at Regensburg along with the bodies of some of the saint's companions and portions of other saints. Having been sent to Magdeburg, these relics were received with great honour by a gathering of the entire populace of the city and of their fellow countrymen. They are still venerated there, to the salvation of the homeland.[9]

Maurice is traditionally depicted in full armor, in Italy emblasoned with a red cross. In folk culture he has become connected with the legend of the Holy Lance, which he is supposed to have carried into battle; his name is engraved on the Holy Lance of Vienna, one of several relics claimed as the spear that pierced Jesus' side on the cross. Saint Maurice gives his name to the town St. Moritz as well as to numerous places called Saint-Maurice in French speaking countries. The Indian Ocean island state of Mauritius was named after Maurice, Prince of Orange, and not directly after Maurice himself.

Over 650 religious foundations dedicated to Saint Maurice can be found in France and other European countries. In Switzerland alone, seven churches or altars in Aargau, six in the Canton of Lucerne, four in the Canton of Solothurn, and one in Appenzell Innerrhoden can be found (in fact, his feast day is a cantonal holiday in Appenzell Innerrhoden).[1] Particularly notable among these are the Church and Abbey of Saint-Maurice-en-Valais, the Church of Saint Moritz in the Engadin, and the Monastery Chapel of Einsiedeln Abbey, where his name continues to be greatly revered. Several orders of chivalry were established in his honor as well, including the Order of the Golden Fleece, Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus and the Order of Saint Maurice.[1] Additionally, fifty-two towns and villages in France have been named in his honor.[10]

Maurice is also the patron saint of a Catholic parish and church in the 9th Ward of New Orleans and including part of the town of Arabi in St. Bernard Parish. The church was constructed in 1856, but was devastated by the winds and flood waters of Hurricane Katrina on 29 August 2005; the copper-plated steeple was blown off the building. The church is currently closed, and the building is for sale.

On 19 July 1941, Pope Pius XII declared Saint Maurice to be patron Saint of the Italian Army's Alpini (mountain infantry corps).[11] The Alpini have celebrated Maurice's feast every year since then.

Patronage

Maurice is the patron saint of the Duchy of Savoy (France) and of the Valais (Switzerland) as well as of soldiers, swordsmiths, armies, and infantrymen. In 1591 Charles Emmanuel I, Duke of Savoy arranged the triumphant return of part of the relics of Saint Maurice from the monastery of Agaune in Valais.[12]

He is also the patron saint of weavers and dyers. Manresa (Spain), Piedmont (Italy), Montalbano Jonico (Italy), Schiavi di Abruzzo (Italy), Stadtsulza (Germany) and Coburg (Germany) have chosen St. Maurice as their patron saint as well. St Maurice is also the patron saint of the Brotherhood of Blackheads, a historical military order of unmarried merchants in present-day Estonia and Latvia.[13] In September 2008, certain relics of Maurice were transferred to a new reliquary and rededicated in Schiavi di Abruzzo (Italy).

Physical characteristics

Because of his name and native land, St. Maurice had been portrayed as black ever since the 12th century. The oldest surviving image that depicts Saint Maurice as a Black African in knight's armour[14] was sculpted in mid-13th century for Magdeburg Cathedral; there it is displayed next to the grave of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor. Jean Devisse, The Image of the Black in Western Art, laid out the documentary sources for the saint's popularity and documented it with illustrative examples.[15][16] When the new cathedral was built under Archbishop Albert II of Käfernberg (served 1205-32), a relic said to be the head of Maurice was procured from the Holy Land.

The image of Saint Maurice has been examined in detail by Gude Suckale-Redlefsen,[17] who demonstrated that this image of Maurice has existed since Maurice's first depiction in Germany between the Weser and the Elbe, and spread to Bohemia, where it became associated with the imperial ambitions of the House of Luxembourg. According to Suckale-Redlefsen, the image of Maurice reached its apogee during the years 1490 to 1530.

Images of the saint died out in the mid-sixteenth century, undermined, Suckale-Redlefsen suggests, by the developing Atlantic slave trade. "Once again, as in the early Middle Ages, the color black had become associated with spiritual darkness and cultural 'otherness'".[18] There is an oil on wood painting of Maurice by Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472–1553) in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.[19]

Gallery

13th Century Statue of Saint Maurice from the Magdeburg Cathedral that bears his name.

13th Century Statue of Saint Maurice from the Magdeburg Cathedral that bears his name. 18th century Baroque sculpture of Saint Maurice on the Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, which was a part of the Austrian Empire in that time, now the Czech Republic.

18th century Baroque sculpture of Saint Maurice on the Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, which was a part of the Austrian Empire in that time, now the Czech Republic. "The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by El Greco. 1580-82

"The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by El Greco. 1580-82- A statue of Saint Maurice, located in Soultz-Haut-Rhin, France.

"The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by Romulo Cincinato. 1583. Oil on canvas, 540 x 288 cm, Monasterio de San Lorenzo, El Escorial, Spain. Cincinnato placed stronger emphasis on the execution scene, which has been brought into the foreground.

"The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice" by Romulo Cincinato. 1583. Oil on canvas, 540 x 288 cm, Monasterio de San Lorenzo, El Escorial, Spain. Cincinnato placed stronger emphasis on the execution scene, which has been brought into the foreground.- Jean Hey. "Portrait of Francis de Chateaubriand Presented by St. Maurice. c. 1500". Tempera on wood. Glasgow Museums and Art Galleries, Glasgow, UK.

St. Maurice as depicted on the City of Coburg's Coat of Arms.

St. Maurice as depicted on the City of Coburg's Coat of Arms. Saint Maurice Stained glass window, Officer Cadet’s Mess, Royal Military College Saint-Jean, St-Jean sur Richelieu, Quebec, Canada

Saint Maurice Stained glass window, Officer Cadet’s Mess, Royal Military College Saint-Jean, St-Jean sur Richelieu, Quebec, Canada The coat of arms of the Brotherhood of Blackheads, featuring Saint Maurice.

The coat of arms of the Brotherhood of Blackheads, featuring Saint Maurice.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Atiya, Azia S., ed. The Coptic Encyclopedia, volume 5, p. 1572. New York, Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 0-02-897034-9.

- 1 2 Mershman, Francis. "St. Maurice," The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 10. New York City: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 6 Mar. 2013

- 1 2 "Maurice – Our Patron Saint".

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: St. Ursus".

- ↑ O'Reilly, Donald F., Lost Legion Recovered, Pen & Sword Military, 2011 ISBN 9781848843783

- ↑ Van Berchem, Denis, The Martyrdom of the Theban Legion, Basel, 1956.

- ↑ Donald F. O'Reilly. The Theban Legion of St. Maurice. Vigiliae Christianae. Vol. 32, No. 3, Sep., 1978.

- ↑ "Our Lady of Laus", Magnificat Vol. XL, No. 5 and Vol. XXXVI, No. 5.

- ↑ Thietmar of Merseburg (2001). Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg. David A. Warner (tr., ed.). Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-7190-4925-3.

- ↑ Butler's Lives of the Saints, New Full Edition, September, p.206. Collegeville, MN:The Liturgical Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8146-2385-9.

- ↑ Esercito Italiano: I Patroni delle Armi Corpi e Specialità - Gli Alpini

- ↑ Vester, Matthew (2013). Sabaudian Studies: Political Culture, Dynasty, and Territory (1400–1700). Truman State University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-61248-094-7.

- ↑ Rannu, Elena. 1993. The Living Past of Tallinn. 3rd ed. Tallinn: Perioodika Publishers. pp. 23-29.

- ↑ Suckale-Redlefsen and Robert Suckale ,(c1987), Mauritius der heilige Mohr/ The Black Saint Maurice,Houston, Texas, Menil Foundation, page 19.

- ↑ Hampton, Grace; Devisse, Jean; Mollat, Michel (1981). "[Review] The Image of the Black in Western Art, Volume II". The Journal of Negro History. The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 66, No. 1. 66 (1): 51–55. doi:10.2307/2716883. JSTOR 2716883.

- ↑ Selzer, Linda Furgerson (1999). "Reading the painterly text: Clarence Major's 'The Slave Trade: View from the Middle Passage". African American Review. African American Review, Vol. 33, No. 2. 33 (2): 209–229. doi:10.2307/2901275. JSTOR 2901275. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ↑ Suckale-Redlefsen and Robert Suckale, Mauritius der heilige Mohr/ The Black Saint Maurice. English translation of foreword and introduction by Genoveva Nitz. (Houston/Zurich) 1988. A catalogue of 205 images of St. Maurice is included.

- ↑ Dorothy Gillerman, reviewing Suckale-Redlefsen 1988 in Speculum 65.3 (July 1990:764 ).

- ↑ "Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop - Saint Maurice - The Metropolitan Museum of Art".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Maurice. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Saint Maurice. |