Order of the Golden Fleece

| Order of the Golden Fleece Orden del Toisón de Oro Ordre de la Toison d'Or Orden vom Goldenen Vlies Ordo Velleris Aurei | |

|---|---|

.png) Insignia of a Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece of Spain. Modern manufacture, Cejalvo (Madrid). | |

| Awarded by the King of Spain and the Head of the House of Habsburg | |

| Established | 1430 |

| Motto |

Pretium Laborum Non Vile Non Aliud |

| Status | Currently constituted |

| Founder | Philip III, Duke of Burgundy |

| Grand Master |

Felipe VI of Spain Archduke Karl of Austria |

| Grades | Knight |

|

| |

The Order of the Golden Fleece (Spanish: Orden del Toisón de Oro,[1] German: Orden vom Goldenen Vlies) is a Roman Catholic order of chivalry founded in Bruges by the Burgundian duke Philip the Good in 1430,[2] to celebrate his marriage to the Portuguese princess Isabella. Today, two branches of the Order exist, namely the Spanish and the Austrian Fleece; the current grand masters are Felipe VI, King of Spain, and Karl von Habsburg, grandson of Emperor Charles I of Austria, respectively. The chaplain of the Austrian branch is Cardinal Graf von Schönborn, Archbishop of Vienna.

Having had only 1,200 recipients ever since its establishment, the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece has been referred to as the most prestigious and exclusive order of chivalry in the world, both historically and contemporaneously.[3][4] Unlike any other distinction, the Golden Fleece is only granted for life, meaning it must be returned to the Spanish Monarch whenever the recipient deceases. Each collar is fully coated in gold, and is estimated to be worth around $60,000 USD, making it the most expensive chivalrous order.[5]

Origin

The Order of the Golden Fleece was established on 10 January 1430, by Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, in celebration of the prosperous and wealthy domains united in his person that ran from Flanders to Switzerland.[6] The jester and dwarf Madame d'Or performed at the creation of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Bruges.[7] It is restricted to a limited number of knights, initially 24 but increased to 30 in 1433, and 50 in 1516, plus the sovereign.[8] The Order's first King of Arms was Jean Le Fèvre de Saint-Remy.[9] It received further privileges unusual to any order of knighthood: the sovereign undertook to consult the order before going to war; all disputes between the knights were to be settled by the order; at each chapter the deeds of each knight were held in review, and punishments and admonitions were dealt out to offenders, and to this the sovereign was expressly subject; the knights could claim as of right to be tried by their fellows on charges of rebellion, heresy and treason, and Charles V conferred on the order exclusive jurisdiction over all crimes committed by the knights; the arrest of the offender had to be by warrant signed by at least six knights, and during the process of charge and trial he remained not in prison but in the gentle custody of his fellow knights.[2] The order, conceived in an ecclesiastical spirit in which mass and obsequies were prominent and the knights were seated in choirstalls like canons,[10] was explicitly denied to heretics, and so became an exclusively Catholic honour during the Reformation. The officers of the order were the chancellor, the treasurer, the registrar, and the King of Arms, or herald, Toison d'Or.

The Duke's stated reason for founding this institution had been given in a proclamation issued following his marriage, in which he wrote that he had done so "for the reverence of God and the maintenance of our Christian Faith, and to honor and exalt the noble order of knighthood, and also ...to do honor to old knights; ...so that those who are at present still capable and strong of body and do each day the deeds pertaining to chivalry shall have cause to continue from good to better; and .. so that those knights and gentlemen who shall see worn the order ... should honor those who wear it, and be encouraged to employ themselves in noble deeds...".[11]

The Order of the Golden Fleece was defended from possible accusations of prideful pomp by the Burgundian court poet Michault Taillevent, who asserted that it was instituted:

| “ | Non point pour jeu ne pour esbatement, |

” |

| “ | Not for amusement nor for recreation, |

” |

The choice of the Golden Fleece of Colchis as the symbol of a Christian order caused some controversy, not so much because of its pagan context, which could be incorporated in chivalric ideals, as in the Nine Worthies, but because the feats of Jason, familiar to all, were not without causes of reproach, expressed in anti-Burgundian terms by Alain Chartier in his Ballade de Fougères referring to Jason as "Who, to carry off the fleece of Colchis, was willing to commit perjury."[13] The bishop of Châlons, chancellor of the Order, rescued the fleece's reputation by identifying it instead with the fleece of Gideon that received the dew of Heaven.[14]

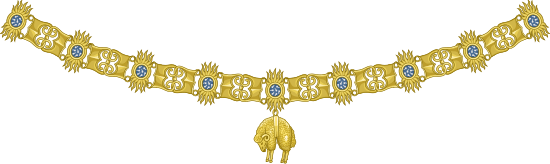

The badge of the Order, in the form of a sheepskin, was suspended from a jewelled collar of firesteels in the shape of the letter B, for Burgundy, linked by flints; with the motto "Pretium Laborum Non Vile" ("No Mean Reward for Labours")[15] engraved on the front of the central link, and Philip's motto "Non Aliud" ("I will have no other") on the back (non-royal knights of the Golden Fleece were forbidden to belong to any other order of knighthood).

Spanish Order

With the absorption of the Burgundian lands into the Spanish Habsburg empire, the sovereignty of the Order passed to the Habsburg kings of Spain, where it remained until the death of the last of the Spanish Habsburgs, Charles II, in 1700. He was succeeded as king by Philip V, a Bourbon. The dispute between Philip and the Habsburg pretender to the Spanish throne, the Archduke Charles, led to the War of the Spanish Succession, and also resulted in the division of the Order into Spanish and Austrian branches. In either case the sovereign, as Duke of Burgundy, writes the letter of appointment in French.

The controversial conferral of the Fleece on Napoleon and his brother Joseph, while Spain was occupied by French troops, angered the exiled King of France, Louis XVIII, and caused him to return his collar in protest. These, and other awards by Joseph, were revoked by King Ferdinand on the restoration of Bourbon rule in 1813. Napoleon created by Order of 15 August 1809 the Order of the Three Golden Fleeces, in view of his sovereignty over Austria, Spain and Burgundy. This was opposed by Joseph I of Spain and appointments to the new order were never made.[16]

In 1812, the acting government of Spain conferred the Fleece upon the Duke of Wellington, an act confirmed by Ferdinand on his resumption of power, with the approval of Pope Pius VII. Wellington therefore became the first Protestant to be honoured with the Golden Fleece. It has subsequently also been conferred upon non-Christians, such as Bhumibol Adulyadej, King of Thailand.

There was another crisis in 1833 when Isabella II became Queen of Spain in defiance of Salic Law that did not allow women to become heads of state. Her right to confer the Fleece was challenged by Spanish Carlists.

Sovereignty remained with the head of the Spanish house of Bourbon during the republican (1931–39) and Francoist (1939–1975) periods and is held today by the present King of Spain, Felipe VI.

Knights of the Order are entitled to be addressed with the style His/Her Excellency in front of their name.[17]

Living members

Below a list of the names of the living knights and ladies, in chronologic order and, within parentheses, the year when they were inducted into the Order:

- King Felipe VI of Spain (1981) – As reigning King of Spain, Sovereign of the Order since 2014 after his father abdicated his rights to him.

- King Juan Carlos I of Spain (1941) – Former Sovereign of the Order as King of Spain from 1975 to 2014.

- King Constantine II of Greece (1964)

- The King of Sweden (1983)[18]

- Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg (1983)[19]

- The Emperor of Japan (1985)[20]

- Princess Beatrix of the Netherlands (1985)[21]

- The Queen of Denmark (1985)[22]

- The Queen of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth Realms (1989)[23]

- King Albert II of Belgium (1994)[24]

- The King of Norway (1995)[25]

- Tsar Simeon II of Bulgaria, Former Prime Minister of the Republic of Bulgaria, 2001–2005 (2004)[26]

- The Grand Duke of Luxembourg (2007)[27]

- Javier Solana (2010)[28]

- Víctor García de la Concha (2010)[29]

- Nicolas Sarkozy, Former President of the French Republic and Co-Prince of Andorra, 2007–2012 (2011) [30][31]

- Enrique Valentín Iglesias García (2014)[32]

- The Princess of Asturias (2015)[33]

Armorial of the Spanish Golden Fleece

Austrian Order

The Austrian Order did not suffer from the political difficulties of the Spanish, remaining (with the exception of the British prince Regent, later George IV) an honour solely for Catholic royalty and nobility. The problem of female inheritance was avoided on the accession of Maria Theresa in 1740 as sovereignty of the Order passed not to herself but to her husband, Francis.

Upon the collapse of the Austrian monarchy after the First World War, King Albert I of Belgium requested that the sovereignty and treasure of the Order be transferred to him as the ruler of the former Habsburg lands of Burgundy. This claim was seriously considered by the victorious allies at Versailles but was eventually rejected due to the intervention of King Alfonso XIII of Spain, who took possession of the property of the Order on behalf of the dethroned emperor, Charles I of Austria. Sovereignty remains with the head of the House of Habsburg, which was handed over on 20 November 2000 by Otto von Habsburg to his elder son, Karl von Habsburg.[34]

Living members

Below a list of the names of the living knights, in chronological order, followed in parentheses by the date, when known, of their induction into the Order:

- The Duke of Bavaria (1960) [35][36]

- Count Johann Larisch of Moennich (1960) [35]

- Archduke Karl of Austria (1961) [35] – Sovereign (Grand Master) of the Order since 2000

- Archduke Andreas Salvator of Austria, Prince of Tuscany [35][37]

- Archduke Carl Salvator of Austria, Prince of Tuscany [35][38]

- Prince Lorenz of Belgium, Archduke of Austria-Este [35][39]

- Archduke Michael of Austria [35][40]

- Archduke Michael Salvator of Austria, Prince of Tuscany [35][41]

- Archduke Georg of Austria [35][42]

- Archduke Carl Christian of Austria [35]

- King Albert II of Belgium [35]

- Grand Duke Jean of Luxembourg [35][43]

- Prince Albrecht of Hohenberg [35][44]

- The Duke of Württemberg [35][45]

- The Prince of Lobkowicz [35]

- Count Johann of Hoyos-Sprinzenstein [35]

- The Prince of Liechtenstein [35][46]

- Prince Clemens of Altenburg [35][47]

- The Duke of Braganza [35][48]

- Count Josef Hubert of Neipperg [35][49]

- The Duke of Hohenberg [35][50]

- The Prince of Schwarzenberg (1991) [35][51]

- Archduke Joseph of Austria (born 1960) [35]

- The Prince of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Rosenberg [35][52]

- Count Gottfried of Czernin of Chudenitz [35]

- Mariano Hugo, Prince of Windisch-Graetz [35][53]

- Baron Johann Friedrich of Solemacher-Antweiler [35]

- Baron Nicolas Adamovich de Csepin [35]

- Bernard Guerrier de Dumast (fr) (2001)

- The Prince of Panagyurishte (2002) [54]

- The King of the Belgians (2008)

- The Prince of Ligne (2011)

- Prince Charles-Louis de Merode (2011)

- Archduke Ferdinand Zvonimir of Austria [55]

- The Margrave of Meissen (2012) [56]

Officials

- Chancellor: Count Alexander von Pachta-Reyhofen (since 2005)

- Grand Chaplain: Christoph Cardinal Schönborn, Archbishop of Vienna (since 1992)

- Chaplain: Count Gregor Henckel-Donnersmarck (since 2007)

- Treasurer: Baron Wulf Gordian von Hauser (since 1992)

- Registrar: Count Karl-Philipp von Clam-Martinic (since 2007)

- Herald: Count Karl-Albrecht von Waldstein-Wartenberg (since 1997)

Chapters of the Order

| Number | Date | City | Temple | Sovereign/Grand Master |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 30 November 1431 | Lille | Saint-Pierre's Collegiate Church | Philip III of Burgundy |

| II | 30 November 1432 | Bruges | St. Donatian's Cathedral | Philip III |

| III | 30 November 1433 | Dijon | Sainte-Chapelle | Philip III |

| IV | 30 November 1435 | Brussels | Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula | Philip III |

| V | 30 November 1436 | Lille | Saint-Pierre's Collegiate Church | Philip III |

| VI | 30 November 1440 | Saint-Omer | Abbey of Saint Bertin | Philip III |

| VII | 30 November 1445 | Ghent | Saint Bavo Cathedral | Philip III |

| VIII | 2 May 1451 | Mons | Sainte-Waudru's Collegiate Church | Philip III |

| IX | 2 May 1456 | The Hague | Grote of Sint-Jacobskerk | Philip III |

| X | 2 May 1461 | Saint-Omer | Abbey of Saint Bertin | Philip III |

| XI | 2 May 1468 | Bruges | Church of Our Lady | Charles I of Burgundy |

| XII | 2 May 1473 | Valenciennes | St. Paul 's Church | Charles I |

| XIII | 30 April 1478 | Bruges | St. Salvator's Cathedral | Maximilian of Austria (Regent of the Order) |

| XIV | 6 May 1481 | 's-Hertogenbosch | St. John's Cathedral | Maximilian of Austria |

| XV | 24 May 1491 | Mechelen | St. Rumbold's Cathedral | Philip IV of Burgundy (Philip I of Castile) |

| XVI | 17 January 1501 | Brussels | Chapel of the Carmelite Convent | Philip IV |

| XVII | 17 December 1505 | Middelburg | ? | Philip IV |

| XVIII | October 1516 | Brussels | Cathedral of St. Michael and St. Gudula | Charles II of Burgundy (Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor) |

| XIX | 5–8 March 1519 | Barcelona | Cathedral of the Holy Cross and St. Eulalia | Charles II |

| XX | 3 December 1531 | Tournai | Cathedral of Our Lady | Charles II |

| XXI | 2 January 1546 | Utrecht | St. Martin's Cathedral | Charles II |

| XXII | 26 January 1555 | Antwerp | Cathedral of Our Lady | Philip V of Burgundy (Philip II of Spain) |

| XXIII | 29 July 1559 | Ghent | Saint Bavo Cathedral | Philip V[57] |

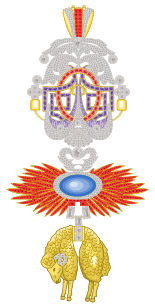

Insignia

|

| Collar (Spanish and Austrian Branches) |

| Spanish Branch | Austrian Branch | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| Sovereign's Neck Insignia | Knight's Neck and Dame's Ribbon Insignia |

Neck Insignia |

See also

- List of Knights of the Golden Fleece

- Jean Le Fèvre de Saint-Remy, first King of Arms to the Order

References

- ↑ Vellus aureum Burgundo-Austriacum sive Augusti et ordinis torquatorum aurei velleris equitum ... relatio historiaca. Ed.I., Antonius Kaschutnig, Paulus-Antonius Gundl

- 1 2

- ↑ D'Arcy Jonathan Dacre Boulton (2000) [February 1987]. The knights of the crown: the monarchical orders of knighthood in later medieval Europe. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-45842-8.

- ↑ "Méndez, Daniel". XLSemanal.

- ↑ "Bandera, María: ¿Qué es el Toisón de Oro y quiénes lo han merecido?". COPE.

- ↑ Gibbons, Rachel (18 January 2013). Exploring history 1400-1900: An anthology of primary sources. Manchester University Press. p. 65. ISBN 9781847792587. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ The Anglo American. 1844. p. 610.

- ↑ "Origins of the Golden Fleece". Antiquesatoz.com. September 8, 1953. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ Buchon, Jean Alexandre (1838). Choix de chroniques et mémoires sur l'histoire de France: avec notices [Selection of chronicles and memoirs on the history of France: with notices] (in French). 2. Paris: Auguste Desrez. pp. xj-xvj (11–16).

- ↑ Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919) 1924:75.

- ↑ Doulton, Op. cit., pp.360–361

- ↑ Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages [1919] 1924:75).

- ↑ "qui pour emportrer la toison De Colcos se veult parjurer."

- ↑ Huizinga 1924:77.

- ↑ "Search object details". British Museum. February 22, 1994. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ Rey y Cabieses, Amadeo-Martín – La descendencia de José Bonaparte, rey de España y de las Indias, slide 22

- ↑ Satow, Ernest Mason, Sir – A Guide to Diplomatic Practice, page 249

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 20 abril 1983 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 22 junio 1983 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 28 febrero 1985 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 8 octubre 1985 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 24 octubre 1985 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 6 mayo 1989 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 17 septiembre 1994 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 25 abril 1995 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 2 octubre 2004 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 14 abril 2007 (accessed on June 9, 2007)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 23 enero 2010 (accessed on January 23, 2010)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 23 enero 2010 (accessed on January 23, 2010)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 26 noviembre 2011 (accessed on October 23, 2016)

- ↑ "iafrica.com | news | world news | Sarkozy to get Golden Fleece". News.iafrica.com. November 25, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 29 marzo 2014 (accessed on March 30, 2014)

- ↑ Spanish: Boletín Oficial del Estado, 31 octubre 2010 (accessed on October 31, 2015)

- ↑ "Schatz des Ordens vom Goldenen Vlies". Die Wiener Schatzkammer. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 "Chevaliers de la Toison d'Or, Toison Autrichienne". Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XVIII (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2007), 4.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 111.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 113.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 95.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 119.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 112.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 94.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XVIII (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2007), 80.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1997), 605.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XVIII (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2007), 122.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XVIII (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2007), 50.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XVI (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2001), 564.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1991), 122.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIX (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2011), 279.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1997), 602.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XV (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 1997), 424.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIX (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2011), 271.

- ↑ Genealogisches Handbuch des Adels, Fürstliche Häuser XIX (Limburg an der Lahn: C.A. Starke, 2011), 436.

- ↑ "The Habsburg Most Illustrious Order of the Golden Fleece: Its Potential Relevance on Modern Culture in the European Union"

- ↑ Bild.de

- ↑ Prince Alexander of Saxony Duke of Saxony

- ↑ Livre du toison d'or, online, fols. 4r-66r

Literature

- Weltliche und Geistliche Schatzkammer. Bildführer. Kunsthistorischen Museum, Vienna. 1987. ISBN 3-7017-0499-6

- Fillitz, Hermann. Die Schatzkammer in Wien: Symbole abendländischen Kaisertums. Vienna, 1986. ISBN 3-7017-0443-0

- Fillitz, Hermann. Der Schatz des Ordens vom Goldenen Vlies. Vienna, 1988. ISBN 3-7017-0541-0

- Boulton, D'Arcy Jonathan Dacre, 1987. The Knights of The Crown: The Monarchical Orders of Knighthood in Later Medieval Europe, 1325–1520, Woodbridge, Suffolk (Boydell Press),(revised edition 2000)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Order of the Golden Fleece. |

- The Society of the golden fleece, an association of people interested in the Order

- The Most Illustrious Order of the Golden Fleece at a reference site on chivalric orders.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)