Theodore Stratelates

| Theodore Stratelates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Great Martyr | |

| Born |

281 Achaea[1] (According to the Coptic Orthodox Church) |

| Died |

319 Heraclea Pontica |

| Venerated in |

Eastern Orthodox Church Coptic Orthodox Church Roman Catholic Church |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Dressed as a warrior , with spear and shield, or as a civilian |

| Patronage | soldiers |

Theodore Stratelates (Greek: Ἅγιος Θεόδωρος ὁ Στρατηλάτης, lit. "the General" or "Military Commander"; Coptic: ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲑⲥⲟⲇⲱⲣⲟⲥ), also known as Theodore of Heraclea (Greek: Θεόδωρος Ἡρακλείας), is a martyr and Warrior Saint venerated with the title Great-martyr in the Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Catholic and Roman Catholic Churches and Oriental Orthodox Churches .

There is much confusion between him and St. Theodore of Amasea and they were in fact probably the same person, whose legends later diverged into two separate traditions.

Life

Theodore came from the city of Euchaita in Asia Minor. He killed a giant serpent living on a precipice in the outskirts of Euchaita. The serpent had terrored the countryside. Theodore armed himself with a sword and vanquished it.[3] According to some of the legends, because of his bravery, Theodore was appointed military-commander (stratelates) in the city of Heraclea Pontica, during the time the emperor Licinius (307–324) began a fierce persecution of Christians. Theodore himself invited Licinius to Heraclea, having promised to offer a sacrifice to the pagan gods. He requested that all the gold and silver statues of the gods which they had in Heraclea be gathered up at his house. Theodore then smashed them into pieces which he then distributed to the poor.

Theodore was arrested and subjected to torture and crucified. His servant Varos (also venerated as a saint), witnessed this and recorded it.[3] In the morning the imperial soldiers found him alive and unharmed. Not wanting to flee a martyr's death, Theodore voluntarily gave himself over again into the hands of Licinius, and was beheaded by the sword. This occurred on 8 February 319, on a Saturday, at the third hour of the day. His "life" is listed in Bibliotecha Hagiographica Graeca 1750-1754[4]

The two St Theodores

Numerous conflicting legends grew up about the life and martyrdom of St Theodore of Amasea so that, in order to bring some consistency into the stories, it seems to have been assumed that there were two different saints, St Theodore Tiron of Amasea and St Theodore Stratelates of Heraclea. The earliest text referring to the two saints is the Laudatio of Niketas David of Paphlagonia in the 9th century. It was said that his Christianity led to many conversions in the Roman army, which was the reason that Licinius was so concerned.[5] Christopher Walter treats at length of the relationship between these saints.[6]

It is suggested that Theodore Tiron as a recruit and ordinary foot soldier was viewed by the people of Byzantium as a patron of common soldiers and that the military aristocracy sought a patron of their own rank.[7]

Another possibility is that he was in fact originally derived from a third St Theodore called St Theodore Orientalis from Anatolia.[8]

In art both Theodore of Amasea and Theodore Stratelates are shown with thick black hair and pointed beards. In older works they were often distinguished by the beard having one point for Theodore Tiron of Amasea and two points for Stratelates as in the fresco from the Zemen Monastery below.[9]

There is much confusion between them and each of them is sometimes said to have had a shrine at Euchaita in Pontus. In fact the shrine existed before any distinction was made between the saints. The separate shrine of Stratelates was at Euchaneia (the modern Çorum in Turkey), a different place about 35 km west of Euchaita (the modern Avkhat).[10]

However, it is now generally accepted, at least in the west, that there was in fact only one St Theodore.[11] Delehaye wrote in 1909 that the existence of the second Theodore had not been historically established,[12] while Walter in 2003 wrote that "the Stratelates is surely a fiction".[13]

The patron saint of Venice before the relics of St Mark were (according to tradition) brought to the city in 828 was St Theodore and the Doge's original chapel was dedicated to that saint, though, after the translation of the relics, it was superseded as his chapel by the church of St Mark.[14] This may be either St Theodore of Amasea or St Theodore Stratelates, but the Venetians do not seem to have distinguished between them. See the section on St Theodore and Venice in the article on Theodore of Amasea.

Byzantine Perspective

St. Gregory of Nyssa, brother of St. Basil the Great (also known as Basil of Caesarea), who is venerated as a saint in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, Lutheranism and Anglicanism, held a different opinion. This is because, although the two Theodores were born in close territories and martyred in parallel, their names were involved in the confusion between two pilgrimage sites. St. Theodore Stratelates was from Euchaneia while St. Theodore Tiron (Ἅγιος Θεόδωρος ὁ Τήρων) was from Euchaita (territories close to each other[15]). Usually mostly western researchers by mistake interpret the lack of reference to two Theodores in the valley of Irida (or Iris) in Yeşilırmak River (up to the 9th century, which was the date that their names were established) as proof that they both were one and the same person.[16] Unfortunately this is not the case since, in fact, each of the saints had his own pilgrimage site. What causes western researchers to get confused is at that time (9th century) the pilgrimage site of Euchaita had declined but that of Euchaneia was starting to flourish.[17]. Also, Avgaros or Uarus (Greek: Αὔγαρος or Οὔαρος) the personal secretary of St. Theodore Stratelates wrote his biography, which clearly differs from the one St. Gregory of Nyssa wrote for St. Theodore Tiron.

Coptic Perspective

St Theodore is known in Egypt as Saint Theodore of Shotep, Saint Tadros of Shotep or Prince Theodore (Coptic: ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲑⲥⲟⲇⲱⲣⲟⲥ; Arabic: الأمير الشهيد تادرس الشطبي, lit. ''Martyr Saint Prince Tadros El Shatby''). He was born to a soldier in the Roman army named John who was Egyptian from the city of Shateb in Upper Egypt. His mother Oussawaia was a prince's daughter. John married her when he went to Antioch to fight against the Persians. When his wife learned that he was a Christian she attempted to make him deny his faith and become a pagan. When John refused, she drove him out of the house. Later, an angel appeared to John and assured him in regards to Theodore, saying that he would be the reason for the faith of many people in Christ. John rejoiced at what he heard and decided to return to his home in Upper Egypt.

The days passed and he grew and was awarded the title of prince because his grandfather was a prince and his mother as well as and his father's high position in the army, his mother sent him to the army to become a soldier, and over the years he became a famous soldier for his courage and skill, and through his friends he knew that his father was a Christian, so he returned to his mother and told her what he had heard, and was angry because she lied to him that his father died in the war.

Here he decided to become a Christian, he went to the priest called Olgianus and asked to rely on the name of Christ. A priest taught him the foundations of Christian faith, Over time he became a brilliant military commander and when Diocletian heard about him, he appointed him a commander over five hundred knights, and called him, Prince Theodore The Esphehlar (brave Commander).

Life continued and someday saint wanted to meet his father and took a search to know his father's home and decided to go to and met him ,he traveled to Alexandria and from there to Shotep ,he went to the church of the city and prayed, and then asked about a person named John, and people told him his place and his severe illness, he went to John house and met him. John was very glad to meet him and thank God for achieving his request and talked together. Five days later, John died, Prince Theodore and people buried him, and offered consolation to Theodore. He told them that when he die they must bury him next to his father John.[18][19] A war was fought between the Persians and the Romans, and the emperor called him to go to Antioch for war so prince left the village and traveled to Antioch and meet St Theodore of Amasea here the story is similar to the above mentioned.[20][21] Many churches have been built on his name since the time of Emperor Constantine, and he currently has many churches named after him throughout Egypt, and for the great fame of the saint in Egypt, including an archaeological monastery in his name in Mona El Amir, Giza .it is said that the body is there after he was attended by his mother when he became a Christian in the reign of Emperor Constantine,[22] an area in Alexandria was named by that name the region became known as Alexandria "Shatby" attributed to him.[23][24][25][26]

Commemoration

His annual feast day is commemorated on 8 February (21 February N.S.); 7 February in the Latin Rite though this is no longer liturgically celebrated in the Roman Catholic church

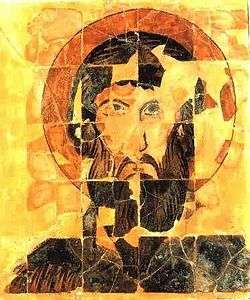

One of the few ceramic icons in existence, dated to c. 900, shows St. Theodore. It was made by the Preslav Literary School and was found 1909 near Preslav, Bulgaria (now National Archaeological Museum, Sofia).

Gallery

Theodore Tiron & Theodore Stratelates (right) from the Harbaville Triptych (Ivory; in the Louvre) from a workshop in Constantinople - mid-10th century

Theodore Tiron & Theodore Stratelates (right) from the Harbaville Triptych (Ivory; in the Louvre) from a workshop in Constantinople - mid-10th century

Theodore of Amasea (on the left) and Theodore Stratelates (on the right) - a fresco from Kremikovtsi Monastery, Bulgaria (16th century?)

Theodore of Amasea (on the left) and Theodore Stratelates (on the right) - a fresco from Kremikovtsi Monastery, Bulgaria (16th century?) Icon of St. Theodore by Simon Ushakov, 1676

Icon of St. Theodore by Simon Ushakov, 1676 Theodore of Amasea (on the left) and Theodore Stratelates (on the right) - a fresco from Rila Monastery, Bulgaria (19th century?)

Theodore of Amasea (on the left) and Theodore Stratelates (on the right) - a fresco from Rila Monastery, Bulgaria (19th century?) Ceramic icon of St. Theodore, Preslav, circa 900 AD, National Archaeological Museum, Sofia but is this Stratelates or Tiron?

Ceramic icon of St. Theodore, Preslav, circa 900 AD, National Archaeological Museum, Sofia but is this Stratelates or Tiron?

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.copticchurch.net/topics/synexarion/theodore.html

- ↑ "St Theodore Stratelates". The Walters Art Museum.

- 1 2 "Greatmartyr Theodore Stratelates 'the General'", Orthodox church in America

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/bibliothecahagi00boll#page/248/mode/2up

- ↑ Walter p.59

- ↑ Walter pp.59-64

- ↑ Grotowski p.119

- ↑ See Walter pp.60-1 & note 93 and fig.57

- ↑ Walter p.60

- ↑ Walter p.58, showing that Delehaye was mistaken in thinking them the same place

- ↑ Delaney pp.547-8. Butler (1995). Butler(1926/38)

- ↑ Delehaye p.15

- ↑ Walter p.59

- ↑ Donald M. Nicol, Byzantium and Venice: A Study in diplomatic and cultural relations (Cambridge: University Press, 1988), pp. 24-26

- ↑ Grotowski p. 101

- ↑ Hippolyte Delehaye (1909) was mistaken in thinking of Euchaita in Pontus and Euchaneia as the same place (Walter p. 58) and this may have caused confusion to many western researchers, questioning at the same time Delehaye's credibility

- ↑ Oikonomidès pp. 327 - 335

- ↑ https://st-takla.org/Saints/Coptic-Orthodox-Saints-Biography/Coptic-Saints-Story_677.html

- ↑ https://copticsaints.wordpress.com/2010/11/24/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%B7%D8%A8%D9%89/

- ↑ http://www.copticchurch.net/topics/synexarion/theodore.html

- ↑ http://www.coptic.org/language/Patron/patron.html

- ↑ http://www.copts-united.com/Article.php?I=1246&A=65083

- ↑ https://copticsaints.wordpress.com/2010/11/24/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%B3-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%B7%D8%A8%D9%89/

- ↑ http://www.copticchurch.net/topics/synexarion/theodore.html

- ↑ http://www.arabchurch.com/forums/showthread.php?t=156531

- ↑ http://www.coptic.org/language/Patron/patron.html

Sources

- Book of Saints, The "A dictionary of servants of God canonised by the Catholic church" compiled by the Benedictine monks of St Augustine's Abbey, Ramsgate (6th edition, revised & rest, 1989)

- Butler's Lives of the Saints (originally compiled by the Revd Alban Butler 1756/59)

- Delaney, John J: Dictionary of Saints (1982)

- Delehaye, Hippolyte: Les Legendes Grecques des Saints Militaires (Paris.1909)

- Demus, Otto: The Church of San Marco in Venice (Washington 1960)

- Demus, Otto: The Mosaics of San Marco in Venice (4 volumes) 1 The Eleventh & Twelfth Centuries - Text (1984)

- Farmer, David: The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (4th edition, 1997)

- Grotowski, Piotr: Arms and Armour of the Warrior Saints: Tradition and Innovation in Byzantine Iconography (843–1261) (Leiden 2010)

- The Oxford Companion to the Year (by Bonnie Blackburn & Leofranc Holford-Stevens) (Oxford 1999)

- Walter, Christopher: The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition (2003)

- Oikonomidès, N.: Le dédoublement de saint Théodore et les villes d΄ `Euhaïta et d΄ `Euchaneia, Analecta Bollandiana 104 (1986) p. 327-335.

- Συναξάριον, Σάββατον Α' Εβδομάδος, ΤΡΙΩΔΙΟΝ ΚΑΤΑΝΥΚΤΙΚΟΝ της Αγίας και Μεγάλης ΤΕΣΣΑΡΑΚΟΣΤΗΣ, εκδόσεις ΦΩΣ, ΑΘΗΝΑ

External links

- Lives of all saints commemorated on February 8 at Orthodox Church in America