Spinal muscular atrophy

| Spinal muscular atrophy | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Autosomal recessive proximal spinal muscular atrophy, 5q spinal muscular atrophy |

| |

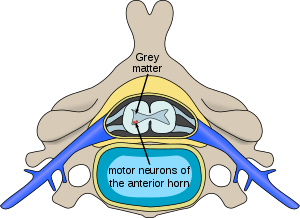

| Location of neurons affected by spinal muscular atrophy in the spinal cord | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a rare neuromuscular disorder characterised by loss of motor neurons and progressive muscle wasting, often leading to early death.

The disorder is caused by a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene, which encodes SMN, a protein widely expressed in all eukaryotic cells (that is, cells with nuclei, including human cells) and necessary for survival of motor neurons. Lower levels of the protein results in loss of function of neuronal cells in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and subsequent system-wide atrophy of skeletal muscles.

Spinal muscular atrophy manifests in various degrees of severity, which all have in common progressive muscle wasting and mobility impairment. Proximal muscles, arm and leg muscles that are closer to the torso and respiratory muscles are affected first. Other body systems may be affected as well, particularly in early-onset forms of the disorder. SMA is the most common genetic cause of infant death.

Spinal muscular atrophy is an inherited disorder and is passed on in an autosomal recessive manner. In December 2016, nusinersen (marketed as Spinraza) became the first approved drug to treat SMA while several other compounds remain in clinical trials.[1]

Classification

SMA manifests over a wide range of severity, affecting infants through adults. The disease spectrum is variously divided into 3–5 types, in accordance either with the age of onset of symptoms or with the highest attained milestone of motor development.

The most commonly used classification is as follows:

| Type | Eponym | Usual age of onset | Characteristics | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA1 (Infantile) |

Werdnig–Hoffmann disease | 0–6 months | The severe form manifests in the first months of life, usually with a quick and unexpected onset ("floppy baby syndrome"). Rapid motor neuron death causes inefficiency of the major bodily organs - especially of the respiratory system - and pneumonia-induced respiratory failure is the most frequent cause of death. Unless placed on mechanical ventilation, babies diagnosed with SMA type 1 do not generally live past two years of age, with death occurring as early as within weeks in the most severe cases (sometimes termed SMA type 0). With proper respiratory support, those with milder SMA type I phenotypes, which account for around 10% of SMA1 cases, are known to live into adolescence and adulthood. | 253300 |

| SMA2 (Intermediate) |

Dubowitz disease | 6–18 months | The intermediate form affects children who are never able to stand and walk but who are able to maintain a sitting position at least some time in their life. The onset of weakness is usually noticed some time between 6 and 18 months. The progress is known to vary greatly, some people gradually grow weaker over time while others through careful maintenance avoid any progression. Scoliosis may be present in these children, and correction with a brace may help improve respiration. Body muscles are weakened, and the respiratory system is a major concern. Life expectancy is reduced but most people with SMA2 live well into adulthood. | 253550 |

| SMA3 (Juvenile) |

Kugelberg–Welander disease | >12 months | The juvenile form usually manifests after 12 months of age and describes people with SMA3 who are able to walk without support at some time, although many later lose this ability. Respiratory involvement is less noticeable, and life expectancy is normal or near normal. | 253400 |

| SMA4 (Adult-onset) |

Adulthood | The adult-onset form (sometimes classified as a late-onset SMA type 3) usually manifests after the third decade of life with gradual weakening of muscles – mainly affects proximal muscles of the extremities – frequently requiring the person to use a wheelchair for mobility. Other complications are rare, and life expectancy is unaffected. | 271150 |

The most severe form of SMA type I is sometimes termed SMA type 0 (or, severe infantile SMA) and is diagnosed in babies that are born so weak that they can survive only a few weeks even with intensive respiratory support. SMA type 0 should not be confused with SMARD1 which may have very similar symptoms and course but has a different genetic cause than SMA.

Motor development in people with SMA is usually assessed using validated functional scales – CHOP INTEND (The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders) in SMA1; and either the Motor Function Measure scale or one of a few variants of Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale[2][3][4][5] in SMA types 2 and 3.

The eponymous label Werdnig–Hoffmann disease (sometimes misspelled with a single n) refers to the earliest clinical descriptions of childhood SMA by Johann Hoffmann and Guido Werdnig. The eponymous term Kugelberg–Welander disease is after Erik Klas Hendrik Kugelberg (1913–1983) and Lisa Welander (1909–2001), who distinguished SMA from muscular dystrophy.[6] Rarely used Dubowitz disease (not to be confused with Dubowitz syndrome) is named after Victor Dubowitz, an English neurologist who authored several studies on the intermediate SMA phenotype.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms vary depending on the SMA type, the stage of the disease as well as individual factors. Signs and symptoms below are most common in the severe SMA type 0/I:[7]

- Areflexia, particularly in extremities

- Overall muscle weakness, poor muscle tone, limpness or a tendency to flop

- Difficulty achieving developmental milestones, difficulty sitting/standing/walking

- In small children: adopting of a frog-leg position when sitting (hips abducted and knees flexed)

- Loss of strength of the respiratory muscles: weak cough, weak cry (infants), accumulation of secretions in the lungs or throat, respiratory distress

- Bell-shaped torso (caused by using only abdominal muscles for respiration) in severe SMA type

- Fasciculations (twitching) of the tongue

- Difficulty sucking or swallowing, poor feeding

Causes

Spinal muscular atrophy is linked to a genetic mutation in the SMN1 gene.[8]

Human chromosome 5 contains two nearly identical genes at location 5q13: a telomeric copy SMN1 and a centromeric copy SMN2. In healthy individuals, the SMN1 gene codes the survival of motor neuron protein (SMN) which, as its name says, plays a crucial role in survival of motor neurons. The SMN2 gene, on the other hand - due to a variation in a single nucleotide (840.C→T) - undergoes alternative splicing at the junction of intron 6 to exon 8, with only 10-20% of SMN2 transcripts coding a fully functional survival of motor neuron protein (SMN-fl) and 80-90% of transcripts resulting in a truncated protein compound (SMNΔ7) which is rapidly degraded in the cell.

In individuals affected by SMA, the SMN1 gene is mutated in such a way that it is unable to correctly code the SMN protein - due to either a deletion occurring at exon 7 or to other point mutations (frequently resulting in the functional conversion of the SMN1 sequence into SMN2). Almost all people, however, have at least one functional copy of the SMN2 gene (with most having 2-4 of them) which still codes small amounts of SMN protein - around 10-20% of the normal level - allowing some neurons to survive. In the long run, however, reduced availability of the SMN protein results in gradual death of motor neuron cells in the anterior horn of spinal cord and the brain. Muscles that depend on these motor neurons for neural input now have decreased innervation (also called denervation), and therefore have decreased input from the central nervous system (CNS). Decreased impulse transmission through the motor neurons leads to decreased contractile activity of the denervated muscle. Consequently, denervated muscles undergo progressive atrophy (waste away).

Muscles of lower extremities are usually affected first, followed by muscles of upper extremities, spine and neck and, in more severe cases, pulmonary and mastication muscles. Proximal muscles are always affected earlier and to a greater degree than distal.[9]

The severity of SMA symptoms is broadly related to how well the remaining SMN2 genes can make up for the loss of function of SMN1. This is partly related to the number of SMN2 gene copies present on the chromosome. Whilst healthy individuals carry two SMN2 gene copies, people with SMA can have anything between 1 and 4 (or more) of them, with the greater the number of SMN2 copies, the milder the disease severity. Thus, most SMA type I babies have one or two SMN2 copies; people with SMA II and III usually have at least three SMN2 copies; and people with SMA IV normally have at least four of them. However, the correlation between symptom severity and SMN2 copy number is not absolute, and there seem to exist other factors affecting the disease phenotype.[10]

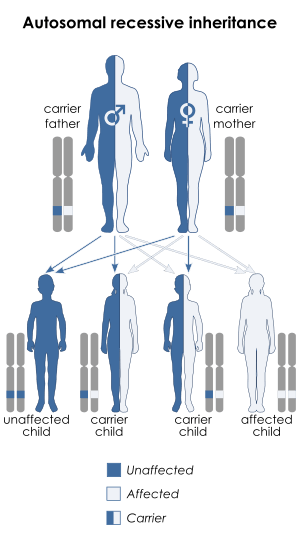

Spinal muscular atrophy is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means that the defective gene is located on an autosome. Two copies of the defective gene - one from each parent - are required to inherit the disorder: the parents may be carriers and not personally affected. SMA seems to appear de novo (i.e., without any hereditary causes) in around 2-4% of cases.

Spinal muscular atrophy affects individuals of all ethnic groups, unlike other well known autosomal recessive disorders, such as sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis, which have significant differences in occurrence rate among ethnic groups. The overall prevalence of SMA, of all types and across all ethnic groups, is in the range of 1 per 10,000 individuals; the gene frequency is around 1:100, therefore, approximately one in 50 persons are carriers.[11][12] There are no known health consequences of being a carrier. A person may learn carrier status only if one's child is affected by SMA or by having the SMN1 gene sequenced.

Affected siblings usually have a very similar form of SMA. However, occurrences of different SMA types among siblings do exist – while rare, these cases might be due to additional de novo deletions of the SMN gene, not involving the NAIP gene, or the differences in SMN2 copy numbers.

Diagnosis

The most severe manifestation on the SMA spectrum can be noticeable to mothers late in their pregnancy by reduced or absent fetal movements. Symptoms are critical (including respiratory distress and poor feeding) which usually result in death within weeks. In comparison to the mildest phenotype of SMA (adult-onset), where muscle weakness may present after decades and progress to the use of a wheelchair but life expectancy is unchanged.[1]

The more common clinical manifestations of the SMA spectrum that prompt diagnostic genetic testing:

- Progressive bilateral muscle weakness (Usually upper arms & legs more so than hands and feet) preceded by an asymptomatic period (all but most severe type 0)[1]

- Flattening of the chest wall when taking a breath and belly protrusion when taking a breath in.

- hypotonia associated with absent reflexes.

While the above symptoms point towards SMA, the diagnosis can only be confirmed with absolute certainty through genetic testing for bi-allelic deletion of exon 7 of the SMN1 gene which is the cause in over 95% of cases.[7] Genetic testing is usually carried out using a blood sample, and MLPA is one of more frequently used genetic testing techniques, as it also allows establishing the number of SMN2 gene copies.[7]

Preimplantation testing

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be used to screen for SMA-affected embryos during in-vitro fertilisation.

Prenatal testing

Prenatal testing for SMA is possible through chorionic villus sampling, cell-free fetal DNA analysis and other methods.

Carrier testing

Those at risk of being carriers of SMN1 deletion, and thus at risk of having offspring affected by SMA, can undergo carrier analysis using a blood or saliva sample. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends all people thinking of becoming pregnant be tested to see if they are a carrier.[13]

Routine screening

Routine prenatal or neonatal screening for SMA is controversial, because of the cost, and because of the severity of the disease. Some researchers have concluded that population screening for SMA is not cost-effective, at a cost of $5 million per case averted in the United States as of 2009.[14] Others conclude that SMA meets the criteria for screening programs and relevant testing should be offered to all couples.[15] The major argument for neonatal screening is that in SMA type I, there is a critical time period in which to initiate therapies to reduce loss of muscle function and proactive treatment in regards to nutrition.[7]

Management

The clinical management of an individual with SMA varies based upon the severity/type. Management of individual patients with the same type of SMA can vary. In the most severe forms (types 0/1), individuals have the greatest muscle weakness requiring prompt intervention. Whereas the least severe form (type 4/adult onset), individuals may not seek the certain aspects of care until later (decades) in life. While types of SMA and individuals among each type may differ, therefore specific aspects of an individual's care can differ.

Respiratory care

The respiratory system is the most common system to be affected and the complications are the leading cause of death in SMA types 0/1 and 2. SMA type 3 can have similar respiratory problems, but it is more rare.[9] The complications that arise due to weakened intercostal muscles because of the lack of stimulation from the nerve. The diaphragm is less affected than the intercostal muscles.[9] Once weakened, the muscles never fully recover the same functional capacity to help in breathing and coughing as well as other functions. Therefore, breathing is more difficult and pose a risk of not getting enough oxygen/shallow breathing and insufficient clearance of airway secretions. These issues more commonly occurs while asleep, when muscles are more relaxed. Swallowing muscles in the pharynx can be affected, leading to aspiration coupled with a poor coughing mechanism increases the likelihood of infection/pneumonia.[16] Mobilizing and clearing secretions involve manual or mechanical chest physiotherapy with postural drainage, and manual or mechanical cough assistance device. To assist in breathing, Non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP) is frequently used and tracheostomy may be sometimes performed in more severe cases;[17] both methods of ventilation prolong survival to a comparable degree, although tracheostomy prevents speech development.[18]

Nutrition

The more severe the type of SMA, the more likely to have nutrition related health issues. Health issues can include difficulty in feeding, jaw opening, chewing and swallowing. Individuals with such difficulties can be at increase risk of over or undernutrition, failure to thrive and aspiration. Other nutritional issues, especially in individuals that are non-ambulatory (more severe types of SMA), include food not passing through the stomach quickly enough, gastric reflux, constipation, vomiting and bloating.[19] Therein, it could be necessary in SMA type I and people with more severe type II to have a feeding tube or gastrostomy.[19][20][21] Additionally, metabolic abnormalities resulting from SMA impair β-oxidation of fatty acids in muscles and can lead to organic acidemia and consequent muscle damage, especially when fasting.[22][23] It is suggested that people with SMA, especially those with more severe forms of the disease, reduce intake of fat and avoid prolonged fasting (i.e., eat more frequently than healthy people)[24] as well as choosing softer foods to avoid aspiration.[16] During an acute illness, especially in children, nutritional problems may first present or can exacerbate an existing problem (example: aspiration) as well as cause other health issues such as electrolyte and blood sugar disturbances.[25]

Orthopaedics

Skeletal problems associated with weak muscles in SMA include tight joints with limited range of movement, hip dislocations, spinal deformity, osteopenia, an increase risk of fractures and pain.[9] Weak muscles that normally stabilize joints such as the vertebral column lead to development of kyphosis and/or scoliosis and joint contracture.[9] Spine fusion is sometimes performed in people with SMA I/II once they reach the age of 8–10 to relieve the pressure of a deformed spine on the lungs. Furthermore, immobile individuals, posture and position on mobility devices as well as range of motion exercises, and bone strengthening can be important to prevent complications.[25] People with SMA might also benefit greatly from various forms of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and physical therapy.

Mobility support

Orthotic devices can be used to support the body and to aid walking. For example, orthotics such as AFOs (ankle foot orthoses) are used to stabilise the foot and to aid gait, TLSOs (thoracic lumbar sacral orthoses) are used to stabilise the torso. Assistive technologies may help in managing movement and daily activity and greatly increase the quality of life.

Cardiology

Although the heart is not a matter of routine concern, a link between SMA and certain heart conditions has been suggested.[26][27][28][29]

Mental health

SMA children do not differ from the general population in their behaviour; their cognitive development can be slightly faster, and certain aspects of their intelligence are above the average.[30][31][32] Despite their disability, SMA-affected people report high degree of satisfaction from life.[33]

Palliative care in SMA has been standardised in the Consensus Statement for Standard of Care in Spinal Muscular Atrophy[9] which has been recommended for standard adoption worldwide.

Medication

Nusinersen is the only approved medication to treat spinal muscular atrophy. It is administered directly to the central nervous system using an intrathecal injection.[34] It was approved by the European Commission in centralised procedure in June 2017.[35]

Prognosis

In lack of pharmacological treatment, people with SMA tend to deteriorate over time. Recently, survival has increased in severe SMA patients with aggressive and proactive supportive respiratory and nutritional support.[36]

The majority of children diagnosed with SMA type 0 and I do not reach the age of 4, recurrent respiratory problems being the primary cause of death.[37] With proper care, milder SMA type I cases (which account for approx. 10% of all SMA1 cases) live into adulthood.[38] Long-term survival in SMA type I is not sufficiently evidenced; however, recent advances in respiratory support seem to have brought down mortality.[39]

In SMA type II, the course of the disease is slower to progress and life expectancy is less than the healthy population. Death before the age of 20 is frequent, although many people with SMA live to become parents and grandparents. SMA type III has normal or near-normal life expectancy if standards of care are followed. Type IV, adult-onset SMA usually means only mobility impairment and does not affect life expectancy.

In all SMA types, physiotherapy has been shown to delay the progress of disease.

Research directions

Since the underlying genetic cause of SMA was identified in 1995,[40] several therapeutic approaches have been proposed and investigated that primarily focus on increasing the availability of SMN protein in motor neurons.[41] The main research directions are as follows:

SMN1 gene replacement

Gene therapy in SMA aims at restoring the SMN1 gene function through inserting specially crafted nucleotide sequence (a SMN1 transgene) into the cell nucleus using a viral vector; scAAV-9 and scAAV-10 are the primary viral vectors under investigation.

Only one programme has reached the clinical stage:

- AVXS-101 – a proprietary biologic under development by Avexis (a Novartis company) which uses self-complementary adeno-associated virus type 9 (scAAV-9) as a vector to deliver the SMN1 transgene. A phase I clinical trial conducted in 2015–2017 showed significant improvement in treated infants compared to the natural course of the disorder.[42] As of September 2018, a number of pivotal trials has been initiated in the US and Europe.[43]

Work on developing gene therapy for SMA is also conducted at the Institut de Myologie in Paris[44] and at the University of Oxford. In 2018, also Biogen announced working on a gene therapy product to treat SMA.[45]

SMN2 alternative splicing modulation

This approach aims at modifying the alternative splicing of the SMN2 gene to force it to code for higher percentage of full-length SMN protein. Sometimes it is also called gene conversion, because it attempts to convert the SMN2 gene functionally into SMN1 gene.

The following splicing modulators have reached clinical stage development:

- Branaplam (LMI070, NVS-SM1) is a proprietary small-molecule experimental drug administered orally and being developed by Novartis. As of October 2017 the compound remains in phase-II clinical trial in infants with SMA type 1 while trials in other patient categories are under development.[46]

- Risdiplam (RG7916, RO7034067) is a proprietary small-molecule drug administered orally and developed by PTC Therapeutics in collaboration with Hoffmann-La Roche and SMA Foundation. As of September 2018, risdiplam has advanced to phase II/III clinical trials across a wide spectrum of spinal muscular atrophy where it has shown encouraging early results.

Of discontinued clinical-stage molecules, RG3039, also known as Quinazoline495, was a proprietary quinazoline derivative developed by Repligen and licensed to Pfizer in March 2014 which was discontinued shortly after, having only completed phase I trials. PTK-SMA1 was a proprietary small-molecule splicing modulator of the tetracyclines group developed by Paratek Pharmaceutical and about to enter clinical development in 2010 which however never happened. RG7800 was a molecule akin to RG7916, developed by Hoffmann-La Roche and trialled on SMA patients in 2015, whose development was put on hold indefinitely due to long-term animal toxicity.

Basic research has also identified other compounds which modified SMN2 splicing in vitro, like sodium orthovanadate[47] and aclarubicin.[48] Morpholino-type antisense oligonucleotides, with the same cellular target as nusinersen, remain a subject of intense research, including at the University College London[49] and at the University of Oxford.[50]

SMN2 gene activation

This approach aims at increasing expression (activity) of the SMN2 gene, thus increasing the amount of full-length SMN protein available.

- Oral salbutamol (albuterol), a popular asthma medicine, showed therapeutic potential in SMA both in vitro[51] and in three small-scale clinical trials involving patients with SMA types 2 and 3,[52][53][54] besides offering respiratory benefits.

A few compounds initially showed promise but failed to demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials:

- Butyrates (sodium butyrate and sodium phenylbutyrate) held some promise in in vitro studies[55][56][57] but a clinical trial in symptomatic people did not confirm their efficacy.[58] Another clinical trial in pre-symptomatic types 1–2 infants was completed in 2015 but no results have been published.[59]

- Valproic acid was used in SMA on an experimental basis in the 1990s and 2000s because in vitro research suggested its moderate effectiveness.[60][61] However, it demonstrated no efficacy in achievable concentrations when subjected to a large clinical trial.[62][63][64] It has also been proposed that it may be effective in a subset of people with SMA but its action may be suppressed by fatty acid translocase in others.[65] Others argue it may actually aggravate SMA symptoms.[66] It is currently not used due to the risk of severe side effects related to long-term use.

- Hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea) was shown effective in mouse models[67] and subsequently commercially researched by Novo Nordisk, Denmark, but demonstrated no effect on people with SMA in subsequent clinical trials.[68]

Compounds which increased SMN2 activity in vitro but did not make it to the clinical stage include growth hormone, various histone deacetylase inhibitors,[69] benzamide M344,[70] hydroxamic acids (CBHA, SBHA, entinostat, panobinostat,[71] trichostatin A,[72][73] vorinostat[74]), prolactin[75] as well as natural polyphenol compounds like resveratrol and curcumin.[76][77] Celecoxib, a p38 pathway activator, is sometimes used off-label by people with SMA based on a single animal study[78] but such use is not backed by clinical-stage research.

SMN stabilisation

SMN stabilisation aims at stabilising the SMNΔ7 protein, the short-lived defective protein coded by the SMN2 gene, so that it is able to sustain neuronal cells.[79]

No compounds have been taken forward to the clinical stage. Aminoglycosides showed capability to increase SMN protein availability in two studies.[80][81] Indoprofen offered some promise in vitro.[82]

Neuroprotection

Neuroprotective drugs aim at enabling the survival of motor neurons even with low levels of SMN protein.

- Olesoxime is a proprietary neuroprotective compound developed by the French company Trophos, later acquired by Hoffmann-La Roche, which showed stabilising effect in a phase-II clinical trial involving people with SMA types 2 and 3. Its development was discontinued in 2018 in view of competition with Spinraza and worse than expected data coming from an open-label extension trial.[83]

Of clinically studied compounds which did not show efficacy, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) held some promise in an open-label uncontrolled clinical trial[84][85][86] but did not prove effective in a subsequent double-blind placebo-controlled trial.[87] Riluzole, a drug that has mild clinical benefit in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, was proposed to be similarly tested in SMA,[88][89] however a 2008–2010 trial in SMA types 2 and 3[90] was stopped early due to lack of satisfactory results.[91]

Compounds that had some neuroprotective effect in in vitro research but never moved to in vivo studies include β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone)[92][93] and follistatin.[94]

Muscle restoration

This approach aims to counter the effect of SMA by targeting the muscle tissue instead of neurons.

- CK-2127107 (CK-107) is a skeletal troponin activator developed by Cytokinetics in cooperation with Astellas. The drug aims at increasing muscle reactivity despite lowered neural signalling. As of October 2016, the molecule is in a phase II clinical trial in adolescent and adults with SMA types 2, 3, and 4.[95]

Stem cells

As of 2016, there has been no significant breakthrough in stem cell therapy in SMA. An experimental programme to develop a stem cell based therapeutic product for SMA was run, with financial support from the SMA community, by a US company California Stem Cell starting from 2005. It was discontinued in 2010, unable to enter the clinical stage, and the company ceased to exist shortly after.

In 2013–2014, a small number of SMA1 children in Italy received court-mandated stem cell injections following the Stamina scam, but the treatment was reported having no effect.[96][97]

Whilst stem cells never form a part of any recognised therapy for SMA, a number of private companies, usually located in countries with lax regulatory oversight, take advantage of media hype and market stem cell injections as a "cure" for a vast range of disorders, including SMA. The medical consensus is that such procedures offer no clinical benefit whilst carrying significant risk, therefore people with SMA are advised against them.[98][99]

Registries

People with SMA in the European Union can participate in clinical research by entering their details into registries managed by TREAT-NMD.[100]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Ottesen, Eric W. (2017-01-01). "ISS-N1 makes the first FDA-approved drug for spinal muscular atrophy". Translational Neuroscience. 8 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2017-0001. PMC 5382937. PMID 28400976.

- ↑ Main, M.; Kairon, H.; Mercuri, E.; Muntoni, F. (2003). "The Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale for Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Scale to Test Ability and Monitor Progress in Children with Limited Ambulation". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 7 (4): 155–9. doi:10.1016/S1090-3798(03)00060-6. PMID 12865054.

- ↑ Krosschell, K. J.; Maczulski, J. A.; Crawford, T. O.; Scott, C.; Swoboda, K. J. (2006). "A modified Hammersmith functional motor scale for use in multi-center research on spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 16 (7): 417–426. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2006.03.015. PMC 3260054. PMID 16750368.

- ↑ O'Hagen, J. M.; Glanzman, A. M.; McDermott, M. P.; Ryan, P. A.; Flickinger, J.; Quigley, J.; Riley, S.; Sanborn, E.; Irvine, C.; Martens, W. B.; Annis, C.; Tawil, R.; Oskoui, M.; Darras, B. T.; Finkel, R. S.; De Vivo, D. C. (2007). "An expanded version of the Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale for SMA II and III patients". Neuromuscular Disorders. 17 (9–10): 693–7. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2007.05.009. PMID 17658255.

- ↑ Glanzman, A. M.; O'Hagen, J. M.; McDermott, M. P.; Martens, W. B.; Flickinger, J.; Riley, S.; Quigley, J.; Montes, J.; Dunaway, S.; Deng, L.; Chung, W. K.; Tawil, R.; Darras, B. T.; De Vivo, D. C.; Kaufmann, P.; Finkel, R. S.; Pediatric Neuromuscular Clinical Research Network for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (PNCR) (2011). "Validation of the Expanded Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type II and III". Journal of Child Neurology. 26 (12): 1499–1507. doi:10.1177/0883073811420294. PMID 21940700.

- ↑ Dubowitz, V. (2009). "Ramblings in the history of spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 19 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2008.10.004. PMID 18951794.

- 1 2 3 4 Oskoui, Darras, DeVivo (2017). "Chapter 1". Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Disease Mechanisms. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-803685-3.

- ↑ Brzustowicz, L. M.; Lehner, T.; Castilla, L. H.; Penchaszadeh, G. K.; Wilhelmsen, K. C.; Daniels, R.; Davies, K. E.; Leppert, M.; Ziter, F.; Wood, D.; Dubowitz, V.; Zerres, K.; Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz, I.; Ott, J.; Munsat, T. L.; Gilliam, T. C. (1990). "Genetic mapping of chronic childhood-onset spinal muscular atrophy to chromosome 5q11.2–13.3". Nature. 344 (6266): 540–1. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..540B. doi:10.1038/344540a0. PMID 2320125.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wang, Ching (Summer 2007). "Consensus Statement for Standard of Care in Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 22: 1027–49. doi:10.1177/0883073807305788. PMID 17761659.

- ↑ Jędrzejowska, M.; Milewski, M.; Zimowski, J.; Borkowska, J.; Kostera-Pruszczyk, A.; Sielska, D.; Jurek, M.; Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz, I. (2009). "Phenotype modifiers of spinal muscular atrophy: The number of SMN2 gene copies, deletion in the NAIP gene and probably gender influence the course of the disease". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 56 (1): 103–8. PMID 19287802.

- ↑ Su, Y. N.; Hung, C. C.; Lin, S. Y.; Chen, F. Y.; Chern, J. P. S.; Tsai, C.; Chang, T. S.; Yang, C. C.; Li, H.; Ho, H. N.; Lee, C. N. (2011). Schrijver, Iris, ed. "Carrier Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) in 107,611 Pregnant Women during the Period 2005–2009: A Prospective Population-Based Cohort Study". PLoS ONE. 6 (2): e17067. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617067S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017067. PMC 3045421. PMID 21364876.

- ↑ Sugarman, E. A.; Nagan, N.; Zhu, H.; Akmaev, V. R.; Zhou, Z.; Rohlfs, E. M.; Flynn, K.; Hendrickson, B. C.; Scholl, T.; Sirko-Osadsa, D. A.; Allitto, B. A. (2011). "Pan-ethnic carrier screening and prenatal diagnosis for spinal muscular atrophy: Clinical laboratory analysis of >72 400 specimens". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.134. PMC 3234503. PMID 21811307.

- ↑ "Carrier Screening in the Age of Genomic Medicine - ACOG". www.acog.org. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ↑ Little, S. E.; Janakiraman, V.; Kaimal, A.; Musci, T.; Ecker, J.; Caughey, A. B. (2010). "The cost-effectiveness of prenatal screening for spinal muscular atrophy". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 202 (3): 253.2e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.032. PMID 20207244.

- ↑ Prior, T. W.; Professional Practice Guidelines Committee (2008). "Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy". Genetics in Medicine. 10 (11): 840–2. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e318188d069. PMC 3110347. PMID 18941424.

- 1 2 Bodamer, olaf (November 2017). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". uptodate.com. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ↑ Bach, J. R.; Niranjan, V.; Weaver, B. (2000). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1: A Noninvasive Respiratory Management Approach". Chest. 117 (4): 1100–5. doi:10.1378/chest.117.4.1100. PMID 10767247.

- ↑ Bach, J. R.; Saltstein, K.; Sinquee, D.; Weaver, B.; Komaroff, E. (2007). "Long-Term Survival in Werdnig–Hoffmann Disease". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 86 (5): 339–45 quiz 346–8, 379. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31804a8505. PMID 17449977.

- 1 2 Messina, S.; Pane, M.; De Rose, P.; Vasta, I.; Sorleti, D.; Aloysius, A.; Sciarra, F.; Mangiola, F.; Kinali, M.; Bertini, E.; Mercuri, E. (2008). "Feeding problems and malnutrition in spinal muscular atrophy type II". Neuromuscular Disorders. 18 (5): 389–393. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2008.02.008. PMID 18420410.

- ↑ Chen, Y. S.; Shih, H. H.; Chen, T. H.; Kuo, C. H.; Jong, Y. J. (2011). "Prevalence and Risk Factors for Feeding and Swallowing Difficulties in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Types II and III". The Journal of Pediatrics. 160 (3): 447–451.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.016. PMID 21924737.

- ↑ Tilton, A.; Miller, M.; Khoshoo, V. (1998). "Nutrition and swallowing in pediatric neuromuscular patients". Seminars in Pediatric Neurology. 5 (2): 106–115. doi:10.1016/S1071-9091(98)80026-0. PMID 9661244.

- ↑ Tein, I.; Sloane, A. E.; Donner, E. J.; Lehotay, D. C.; Millington, D. S.; Kelley, R. I. (1995). "Fatty acid oxidation abnormalities in childhood-onset spinal muscular atrophy: Primary or secondary defect(s)?". Pediatric neurology. 12 (1): 21–30. doi:10.1016/0887-8994(94)00100-G. PMID 7748356.

- ↑ Crawford, T. O.; Sladky, J. T.; Hurko, O.; Besner-Johnston, A.; Kelley, R. I. (1999). "Abnormal fatty acid metabolism in childhood spinal muscular atrophy". Annals of Neurology. 45 (3): 337–343. doi:10.1002/1531-8249(199903)45:3<337::AID-ANA9>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 10072048.

- ↑ Leighton, S. (2003). "Nutrition issues associated with spinal muscular atrophy". Nutrition & Dietetics. 60 (2): 92–96.

- 1 2 Apkon, Susan (Summer 2017). "SMA CARE SERIES - Musculoskeletal System" (PDF). www.curesma.org.

- ↑ Rudnik-Schoneborn, S.; Heller, R.; Berg, C.; Betzler, C.; Grimm, T.; Eggermann, T.; Eggermann, K.; Wirth, R.; Wirth, B.; Zerres, K. (2008). "Congenital heart disease is a feature of severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (10): 635–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.057950. PMID 18662980.

- ↑ Heier, C. R.; Satta, R.; Lutz, C.; Didonato, C. J. (2010). "Arrhythmia and cardiac defects are a feature of spinal muscular atrophy model mice". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (20): 3906–18. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq330. PMC 2947406. PMID 20693262.

- ↑ Shababi, M.; Habibi, J.; Yang, H. T.; Vale, S. M.; Sewell, W. A.; Lorson, C. L. (2010). "Cardiac defects contribute to the pathology of spinal muscular atrophy models". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (20): 4059–71. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq329. PMID 20696672.

- ↑ Bevan, A. K.; Hutchinson, K. R.; Foust, K. D.; Braun, L.; McGovern, V. L.; Schmelzer, L.; Ward, J. G.; Petruska, J. C.; Lucchesi, P. A.; Burghes, A. H. M.; Kaspar, B. K. (2010). "Early heart failure in the SMNΔ7 model of spinal muscular atrophy and correction by postnatal scAAV9-SMN delivery". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (20): 3895–3905. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq300. PMC 2947399. PMID 20639395.

- ↑ Von Gontard, A.; Zerres, K.; Backes, M.; Laufersweiler-Plass, C.; Wendland, C.; Melchers, P.; Lehmkuhl, G.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S. (2002). "Intelligence and cognitive function in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 12 (2): 130–6. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(01)00274-7. PMID 11738354.

- ↑ Billard, C.; Gillet, P.; Signoret, J. L.; Uicaut, E.; Bertrand, P.; Fardeau, M.; Barthez-Carpentier, M. A.; Santini, J. J. (1992). "Cognitive functions in duchenne muscular dystrophy: A reappraisal and comparison with spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 2 (5–6): 371–8. doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(06)80008-8. PMID 1300185.

- ↑ Laufersweiler-Plass, C.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, S.; Zerres, K.; Backes, M.; Lehmkuhl, G.; Von Gontard, A. (2002). "Behavioural problems in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy and their siblings". Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 45. doi:10.1017/S0012162203000082. PMID 12549754.

- ↑ De Oliveira, C. M.; Araújo, A. P. D. Q. C. (2011). "Self-reported quality of life has no correlation with functional status in children and adolescents with spinal muscular atrophy". European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 15 (1): 36–39. doi:10.1016/j.ejpn.2010.07.003. PMID 20800519.

- ↑ Grant, Charley (2016-12-27). "Surprise Drug Approval Is Holiday Gift for Biogen". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 2016-12-27.

- ↑ "SPINRAZA® (Nusinersen) Approved in the European Union as First Treatment for Spinal Muscular Atrophy". AFP. 2017-06-01. Retrieved 2017-06-01.

- ↑ Darras, Finkel (2017). Spinal Muscular Atrophy. United Kingdom, United States: Elsevier. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-12-803685-3.

- ↑ Yuan, N.; Wang, C. H.; Trela, A.; Albanese, C. T. (2007). "Laparoscopic Nissen Fundoplication During Gastrostomy Tube Placement and Noninvasive Ventilation May Improve Survival in Type I and Severe Type II Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 22 (6): 727–731. doi:10.1177/0883073807304009. PMID 17641258.

- ↑ Bach, J. R. (2007). "Medical Considerations of Long-Term Survival of Werdnig–Hoffmann Disease". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 86 (5): 349–55. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31804b1d66. PMID 17449979.

- ↑ Oskoui, M; Levy, G; Garland, C. J.; Gray, J. M.; O'Hagen, J; De Vivo, D. C.; Kaufmann, P (2007). "The changing natural history of spinal muscular atrophy type 1". Neurology. 69 (20): 1931–6. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000290830.40544.b9. PMID 17998484.

- ↑ Lefebvre, Suzie; Bürglen, Lydie; Reboullet, Sophie; Clermont, Olivier; Burlet, Philippe; Viollet, Louis; Benichou, Bernard; Cruaud, Corinne; Millasseau, Philippe (1995). "Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene". Cell. 80 (1): 155–165. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(95)90460-3. PMID 7813012.

- ↑ d’Ydewalle, Constantin; Sumner, Charlotte J. (2015-01-29). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Therapeutics: Where do we Stand?". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (2): 303–316. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0337-y. PMC 4404440. PMID 25631888.

- ↑ "AveXis Reports Data from Ongoing Phase 1 Trial of AVXS-101 in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type 1".

- ↑ "AveXis Announces Single-Arm Design for European Pivotal Study of AVXS-101 in SMA Type 1 Patients". Avexis. 2017-02-06.

- ↑ Benkhelifa-Ziyyat, Sofia; Besse, Aurore; Roda, Marianne; Duque, Sandra; Astord, Stéphanie; Carcenac, Romain; Marais, Thibaut; Barkats, Martine (2013). "Intramuscular scAAV9-SMN Injection Mediates Widespread Gene Delivery to the Spinal Cord and Decreases Disease Severity in SMA Mice". Molecular Therapy. 21 (2): 282–290. doi:10.1038/mt.2012.261. PMC 3594018. PMID 23295949.

- ↑ "Biogen Releases Community Statement on Spinraza Access and New Data | Cure SMA". www.curesma.org. Retrieved 2018-09-11.

- ↑ "Novartis Releases Update on LMI070 (Branaplam) Clinical Trial". CureSMA. Retrieved 2017-10-07.

- ↑ Zhang, M. L.; Lorson, C. L.; Androphy, E. J.; Zhou, J. (2001). "An in vivo reporter system for measuring increased inclusion of exon 7 in SMN2 mRNA: Potential therapy of SMA". Gene Therapy. 8 (20): 1532–8. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3301550. PMID 11704813.

- ↑ Andreassi, C.; Jarecki, J.; Zhou, J.; Coovert, D. D.; Monani, U. R.; Chen, X.; Whitney, M.; Pollok, B.; Zhang, M.; Androphy, E.; Burghes, A. H. (2001). "Aclarubicin treatment restores SMN levels to cells derived from type I spinal muscular atrophy patients". Human Molecular Genetics. 10 (24): 2841–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/10.24.2841. PMID 11734549.

- ↑ Zhou, Haiyan; Meng, Jinhong; Marrosu, Elena; Janghra, Narinder; Morgan, Jennifer; Muntoni, Francesco (2015). "Repeated low doses of morpholino antisense oligomer: An intermediate mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy to explore the window of therapeutic response". Human Molecular Genetics. 24 (22): 6265–77, 6265. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddv329. PMC 4614699. PMID 26264577.

- ↑ Hammond, Suzan M.; Hazell, Gareth; Shabanpoor, Fazel; Saleh, Amer F.; Bowerman, Melissa; Sleigh, James N.; Meijboom, Katharina E.; Zhou, Haiyan; Muntoni, Francesco (2016-09-27). "Systemic peptide-mediated oligonucleotide therapy improves long-term survival in spinal muscular atrophy". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (39): 10962–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605731113. PMC 5047168. PMID 27621445.

- ↑ Angelozzi, C.; Borgo, F.; Tiziano, F. D.; Martella, A.; Neri, G.; Brahe, C. (2007). "Salbutamol increases SMN mRNA and protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy cells". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (1): 29–31. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.051177. PMID 17932121.

- ↑ Pane, M.; Staccioli, S.; Messina, S.; d'Amico, A.; Pelliccioni, M.; Mazzone, E. S.; Cuttini, M.; Alfieri, P.; Battini, R.; Main, M.; Muntoni, F.; Bertini, E.; Villanova, M.; Mercuri, E. (2008). "Daily salbutamol in young patients with SMA type II". Neuromuscular Disorders. 18 (7): 536–540. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.004. PMID 18579379.

- ↑ Tiziano, F. D.; Lomastro, R.; Pinto, A. M.; Messina, S.; d'Amico, A.; Fiori, S.; Angelozzi, C.; Pane, M.; Mercuri, E.; Bertini, E.; Neri, G.; Brahe, C. (2010). "Salbutamol increases survival motor neuron (SMN) transcript levels in leucocytes of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patients: Relevance for clinical trial design". Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (12): 856–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2010.080366. PMID 20837492.

- ↑ Morandi, L. (2013). "P.6.4 Salbutamol tolerability and efficacy in adult type III SMA patients: Results of a multicentric, molecular and clinical, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Neuromuscular Disorders. 23 (9–10): 771. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2013.06.475.

- ↑ Chang, J. -G.; Hsieh-Li, H. -M.; Jong, Y. -J.; Wang, N. M.; Tsai, C. -H.; Li, H. (2001). "Treatment of spinal muscular atrophy by sodium butyrate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (17): 9808–13. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.9808C. doi:10.1073/pnas.171105098. PMC 55534. PMID 11504946.

- ↑ Andreassi, C.; Angelozzi, C.; Tiziano, F. D.; Vitali, T.; De Vincenzi, E.; Boninsegna, A.; Villanova, M.; Bertini, E.; Pini, A.; Neri, G.; Brahe, C. (2003). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN expression in vitro: Relevance for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy". European Journal of Human Genetics. 12 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201102. PMID 14560316.

- ↑ Brahe, C.; Vitali, T.; Tiziano, F. D.; Angelozzi, C.; Pinto, A. M.; Borgo, F.; Moscato, U.; Bertini, E.; Mercuri, E.; Neri, G. (2004). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN gene expression in spinal muscular atrophy patients". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (2): 256–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201320. PMID 15523494.

- ↑ Mercuri, E.; Bertini, E.; Messina, S.; Solari, A.; d'Amico, A.; Angelozzi, C.; Battini, R.; Berardinelli, A.; Boffi, P.; Bruno, C.; Cini, C.; Colitto, F.; Kinali, M.; Minetti, C.; Mongini, T.; Morandi, L.; Neri, G.; Orcesi, S.; Pane, M.; Pelliccioni, M.; Pini, A.; Tiziano, F. D.; Villanova, M.; Vita, G.; Brahe, C. (2007). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of phenylbutyrate in spinal muscular atrophy". Neurology. 68 (1): 51–55. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000249142.82285.d6. PMID 17082463.

- ↑ "Study to Evaluate Sodium Phenylbutyrate in Pre-symptomatic Infants With Spinal Muscular Atrophy (STOPSMA)". Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ↑ Brichta, L.; Hofmann, Y.; Hahnen, E.; Siebzehnrubl, F. A.; Raschke, H.; Blumcke, I.; Eyupoglu, I. Y.; Wirth, B. (2003). "Valproic acid increases the SMN2 protein level: A well-known drug as a potential therapy for spinal muscular atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (19): 2481–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg256. PMID 12915451.

- ↑ Tsai, L. K.; Tsai, M. S.; Ting, C. H.; Li, H. (2008). "Multiple therapeutic effects of valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy model mice". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 86 (11): 1243–54. doi:10.1007/s00109-008-0388-1. PMID 18649067.

- ↑ Swoboda, K. J.; Scott, C. B.; Crawford, T. O.; Simard, L. R.; Reyna, S. P.; Krosschell, K. J.; Acsadi, G.; Elsheik, B.; Schroth, M. K.; d'Anjou, G.; Lasalle, B.; Prior, T. W.; Sorenson, S. L.; MacZulski, J. A.; Bromberg, M. B.; Chan, G. M.; Kissel, J. T.; Project Cure Spinal Muscular Atrophy Investigators Network (2010). Boutron, Isabelle, ed. "SMA CARNI-VAL Trial Part I: Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of L-Carnitine and Valproic Acid in Spinal Muscular Atrophy". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e12140. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512140S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012140. PMC 2924376. PMID 20808854.

- ↑ Kissel, J. T.; Scott, C. B.; Reyna, S. P.; Crawford, T. O.; Simard, L. R.; Krosschell, K. J.; Acsadi, G.; Elsheik, B.; Schroth, M. K.; d'Anjou, G.; Lasalle, B.; Prior, T. W.; Sorenson, S.; MacZulski, J. A.; Bromberg, M. B.; Chan, G. M.; Swoboda, K. J.; Project Cure Spinal Muscular Atrophy Investigators' Network (2011). Feany, Mel B., ed. "SMA CARNI-VAL TRIAL PART II: A Prospective, Single-Armed Trial of L-Carnitine and Valproic Acid in Ambulatory Children with Spinal Muscular Atrophy". PLoS ONE. 6 (7): e21296. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621296K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021296. PMC 3130730. PMID 21754985.

- ↑ Darbar, I. A.; Plaggert, P. G.; Resende, M. B. D.; Zanoteli, E.; Reed, U. C. (2011). "Evaluation of muscle strength and motor abilities in children with type II and III spinal muscle atrophy treated with valproic acid". BMC Neurology. 11: 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2377-11-36. PMC 3078847. PMID 21435220.

- ↑ Garbes, L.; Heesen, L.; Holker, I.; Bauer, T.; Schreml, J.; Zimmermann, K.; Thoenes, M.; Walter, M.; Dimos, J.; Peitz, M.; Brustle, O.; Heller, R.; Wirth, B. (2012). "VPA response in SMA is suppressed by the fatty acid translocase CD36". Human Molecular Genetics. 22 (2): 398–407. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds437. PMID 23077215.

- ↑ Rak, K.; Lechner, B. D.; Schneider, C.; Drexl, H.; Sendtner, M.; Jablonka, S. (2009). "Valproic acid blocks excitability in SMA type I mouse motor neurons". Neurobiology of Disease. 36 (3): 477–487. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2009.08.014. PMID 19733665.

- ↑ Grzeschik, S. M.; Ganta, M.; Prior, T. W.; Heavlin, W. D.; Wang, C. H. (2010). "Hydroxyurea enhances SMN2 gene expression in spinal muscular atrophy cells". Annals of Neurology. 58 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1002/ana.20548. PMID 16049920.

- ↑ Chen, T. - H.; Chang, J. - G.; Yang, Y. - H.; Mai, H. - H.; Liang, W. - C.; Wu, Y. - C.; Wang, H. - Y.; Huang, Y. - B.; Wu, S. - M.; Chen, Y. - C.; Yang, S. - N.; Jong, Y. - J. (2010). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydroxyurea in spinal muscular atrophy". Neurology. 75 (24): 2190–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020332. PMID 21172842.

- ↑ Evans, M. C.; Cherry, J. J.; Androphy, E. J. (2011). "Differential regulation of the SMN2 gene by individual HDAC proteins". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 414 (1): 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.011. PMID 21925145.

- ↑ Riessland, M.; Brichta, L.; Hahnen, E.; Wirth, B. (2006). "The benzamide M344, a novel histone deacetylase inhibitor, significantly increases SMN2 RNA/protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy cells". Human Genetics. 120 (1): 101–110. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0186-1. PMID 16724231.

- ↑ Garbes, L.; Riessland, M.; Hölker, I.; Heller, R.; Hauke, J.; Tränkle, C.; Coras, R.; Blümcke, I.; Hahnen, E.; Wirth, B. (2009). "LBH589 induces up to 10-fold SMN protein levels by several independent mechanisms and is effective even in cells from SMA patients non-responsive to valproate". Human Molecular Genetics. 18 (19): 3645–58. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp313. PMID 19584083.

- ↑ Narver, H. L.; Kong, L.; Burnett, B. G.; Choe, D. W.; Bosch-Marcé, M.; Taye, A. A.; Eckhaus, M. A.; Sumner, C. J. (2008). "Sustained improvement of spinal muscular atrophy mice treated with trichostatin a plus nutrition". Annals of Neurology. 64 (4): 465–470. doi:10.1002/ana.21449. PMID 18661558.

- ↑ Avila, A. M.; Burnett, B. G.; Taye, A. A.; Gabanella, F.; Knight, M. A.; Hartenstein, P.; Cizman, Z.; Di Prospero, N. A.; Pellizzoni, L.; Fischbeck, K. H.; Sumner, C. J. (2007). "Trichostatin a increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 117 (3): 659–671. doi:10.1172/JCI29562. PMC 1797603. PMID 17318264.

- ↑ Riessland, M.; Ackermann, B.; Förster, A.; Jakubik, M.; Hauke, J.; Garbes, L.; Fritzsche, I.; Mende, Y.; Blumcke, I.; Hahnen, E.; Wirth, B. (2010). "SAHA ameliorates the SMA phenotype in two mouse models for spinal muscular atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (8): 1492–1506. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq023. PMID 20097677.

- ↑ Farooq, F.; Molina, F. A. A.; Hadwen, J.; MacKenzie, D.; Witherspoon, L.; Osmond, M.; Holcik, M.; MacKenzie, A. (2011). "Prolactin increases SMN expression and survival in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy via the STAT5 pathway". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 121 (8): 3042–50. doi:10.1172/JCI46276. PMC 3148738. PMID 21785216.

- ↑ Sakla, M. S.; Lorson, C. L. (2007). "Induction of full-length survival motor neuron by polyphenol botanical compounds". Human Genetics. 122 (6): 635–643. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0441-0. PMID 17962980.

- ↑ Dayangaç-Erden, D.; Bora, G.; Ayhan, P.; Kocaefe, Ç.; Dalkara, S.; Yelekçi, K.; Demir, A. S.; Erdem-Yurter, H. (2009). "Histone Deacetylase Inhibition Activity and Molecular Docking of (E)-Resveratrol: Its Therapeutic Potential in Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 73 (3): 355–364. doi:10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00781.x. PMID 19207472.

- ↑ Farooq, F.; Abadia-Molina, F.; MacKenzie, D.; Hadwen, J.; Shamim, F.; O'Reilly, S.; Holcik, M.; MacKenzie, A. (2013). "Celecoxib increases SMN and survival in a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model via p38 pathway activation". Human Molecular Genetics. 22 (17): 3415–24. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt191. PMID 23656793.

- ↑ Burnett, B. G.; Munoz, E.; Tandon, A.; Kwon, D. Y.; Sumner, C. J.; Fischbeck, K. H. (2008). "Regulation of SMN Protein Stability". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 29 (5): 1107–15. doi:10.1128/MCB.01262-08. PMC 2643817. PMID 19103745.

- ↑ Mattis, V. B.; Rai, R.; Wang, J.; Chang, C. W. T.; Coady, T.; Lorson, C. L. (2006). "Novel aminoglycosides increase SMN levels in spinal muscular atrophy fibroblasts". Human Genetics. 120 (4): 589–601. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0245-7. PMID 16951947.

- ↑ Mattis, V. B.; Fosso, M. Y.; Chang, C. W.; Lorson, C. L. (2009). "Subcutaneous administration of TC007 reduces disease severity in an animal model of SMA". BMC Neuroscience. 10: 142. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-142. PMC 2789732. PMID 19948047.

- ↑ Lunn, M. R.; Root, D. E.; Martino, A. M.; Flaherty, S. P.; Kelley, B. P.; Coovert, D. D.; Burghes, A. H.; Thi Man, N.; Morris, G. E.; Zhou, J.; Androphy, E. J.; Sumner, C. J.; Stockwell, B. R. (2004). "Indoprofen Upregulates the Survival Motor Neuron Protein through a Cyclooxygenase-Independent Mechanism". Chemistry & Biology. 11 (11): 1489–93. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.024. PMC 3160629. PMID 15555999.

- ↑ Taylor, Nick P. (2018-06-01). "Roche scraps €120M SMA drug after hitting 'many difficulties'". www.fiercebiotech.com. Retrieved 2018-06-08.

- ↑ Takeuchi, Y.; Miyanomae, Y.; Komatsu, H.; Oomizono, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Okano, S.; Nishiki, T.; Sawada, T. (1994). "Efficacy of Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone in the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 9 (3): 287–9. doi:10.1177/088307389400900313. PMID 7930408.

- ↑ Tzeng, A. C.; Cheng, J.; Fryczynski, H.; Niranjan, V.; Stitik, T.; Sial, A.; Takeuchi, Y.; Foye, P.; Deprince, M.; Bach, J. R. (2000). "A study of thyrotropin-releasing hormone for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy: A preliminary report". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 79 (5): 435–440. doi:10.1097/00002060-200009000-00005. PMID 10994885.

- ↑ Kato, Z.; Okuda, M.; Okumura, Y.; Arai, T.; Teramoto, T.; Nishimura, M.; Kaneko, H.; Kondo, N. (2009). "Oral Administration of the Thyrotropin-Releasing Hormone (TRH) Analogue, Taltireline Hydrate, in Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 24 (8): 1010–1012. doi:10.1177/0883073809333535. PMID 19666885.

- ↑ Bosboom, W. M.; Vrancken, A. F. E.; Van Den Berg, L. H.; Wokke, J. H.; Iannaccone, S. T. (2009). Bosboom, Wendy MJ, ed. "Drug treatment for spinal muscular atrophy type I". The Cochrane Library. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006281.pub2. PMID 19160274.

- ↑ Haddad, Hafedh; Cifuentes-Diaz, Carmen; Miroglio, Audrey; Roblot, Natacha; Joshi, Vandana; Melki, Judith (2003). "Riluzole attenuates spinal muscular atrophy disease progression in a mouse model". Muscle & Nerve. 28 (4): 432–7. doi:10.1002/mus.10455. PMID 14506714.

- ↑ Dimitriadi, M.; Kye, M. J.; Kalloo, G.; Yersak, J. M.; Sahin, M.; Hart, A. C. (2013). "The Neuroprotective Drug Riluzole Acts via Small Conductance Ca2+-Activated K+ Channels to Ameliorate Defects in Spinal Muscular Atrophy Models". Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (15): 6557–62, p. 6557. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1536-12.2013. PMC 3652322. PMID 23575853.

- ↑ "Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Riluzole in Children and Young Adults With Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)". ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ↑ "Riluzole: premiers résultats décevants" (in French). AFM Téléthon. 2010-09-22.

- ↑ Nizzardo, M.; Nardini, M.; Ronchi, D.; Salani, S.; Donadoni, C.; Fortunato, F.; Colciago, G.; Falcone, M.; Simone, C.; Riboldi, G.; Govoni, A.; Bresolin, N.; Comi, G. P.; Corti, S. (2011). "Beta-lactam antibiotic offers neuroprotection in a spinal muscular atrophy model by multiple mechanisms". Experimental Neurology. 229 (2): 214–225. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.01.017. PMID 21295027.

- ↑ Hedlund, E. (2011). "The protective effects of beta-lactam antibiotics in motor neuron disorders". Experimental Neurology. 231 (1): 14–18. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.002. PMID 21693120.

- ↑ Rose, F. F.; Mattis, V. B.; Rindt, H.; Lorson, C. L. (2009). "Delivery of recombinant follistatin lessens disease severity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 18 (6): 997–1005. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn426. PMC 2649020. PMID 19074460.

- ↑ "CK-2127107".

- ↑ Carrozzi, Marco; Amaddeo, Alessandro; Biondi, Andrea; Zanus, Caterina; Monti, Fabrizio; Alessandro, Ventura (2012). "Stem cells in severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1)". Neuromuscular Disorders. 22 (11): 1032–4. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2012.09.005. PMID 23046997.

- ↑ Mercuri, Eugenio; Bertini, Enrico (2012). "Stem cells in severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 22 (12): 1105. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2012.11.001. PMID 23206850.

- ↑ Committee for Advanced Therapies CAT Scientific Secretariat. (2010). "Use of unregulated stem-cell based medicinal products". The Lancet. 376 (9740): 514. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61249-4. PMID 20709228.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (16 April 2010). "Concerns over unregulated medicinal products containing stem cells" (PDF). European Medicines Agency.

- ↑ "National registries for DMD, SMA and DM". Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

Further reading

- Parano, E; Pavone, L; Falsaperla, R; Trifiletti, R; Wang, C (Aug 1996). "Molecular basis of phenotypic heterogeneity in siblings with spinal muscular atrophy". Annals of Neurology. 40 (2): 247–51. doi:10.1002/ana.410400219. PMID 8773609.

- Wang C. H. (2007). "Consensus Statement for Standard of Care in Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 22: 1027–49. doi:10.1177/0883073807305788. PMID 17761659.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- SMA at NINDS

- Spinal muscular atrophy at Curlie (based on DMOZ)