Primary progressive aphasia

| Primary progressive aphasia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | neurology |

| OMIM | 607485 |

| MeSH | D018888 |

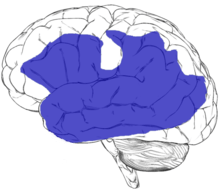

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a type of neurological syndrome in which language capabilities slowly and progressively become impaired. As with other types of aphasia, the symptoms that accompany PPA depend on what parts of the left hemisphere are significantly damaged. However, unlike most other aphasias, PPA results from continuous deterioration in brain tissue, which leads to early symptoms being far less detrimental than later symptoms. Those with PPA slowly lose the ability to speak, write, read, and generally comprehend language. Eventually, almost every patient becomes mute and completely loses the ability to understand both written and spoken language.[1] Although it was first described as solely impairment of language capabilities while other mental functions remain intact,[1] it is now recognized that many, if not most of those afflicted suffer impairment of memory, short term memory formation and loss of executive functions. It was first described as a distinct syndrome by M.-Marsel Mesulam in 1982.[2] Primary progressive aphasias have a clinical and pathological overlap with the frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) spectrum of disorders and Alzheimer's disease. However, PPA is not considered synonymous to Alzheimer's disease due to the fact that, unlike those affected by Alzheimer's disease, those with PPA are generally able to maintain the ability to care for themselves, remain employed, and pursue interests and hobbies. Moreover, in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, Pick's disease, and Creutzfeld-Jakob disease, progressive deterioration of comprehension and production of language is just one of the many possible types of mental deterioration, such as the progressive decline of memory, motor skills, reasoning, awareness, and visuospatial skills.[1]

Classification

Three classifications of primary progressive aphasia have been described.[3][4][5] In the classical Mesulam criteria for primary progressive aphasia, there are two variants: a non-fluent type progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) and a fluent type semantic dementia (SD).[6][7] A third variant of primary progressive aphasia, logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA),[8] is an atypical form of Alzheimer's disease. Early PNFA can include such features as speech apraxia, effortful speech, and anomia, and thus can resemble Broca’s aphasia. Early LPA involves impairments in naming and sentence repetition, and thus can resemble Conduction aphasia. However, these PPA subtypes differ from these similar aphasias, as these subtypes do not occur acutely following trauma to the brain, such as following a stroke, due to differing functional and structural neuroanatomical patterns of involvement and the progressive nature of the disease.[9]

Diagnostic criteria

The following diagnosis criteria were defined by Mesulam:[10][11]

- As opposed to having followed trauma to the brain, a patient must show an insidious onset and a gradual progression of aphasia, defined as a disorder of sentence and/or word usage, affecting the production and comprehension of speech.

- The disorder in question must be the only determinant on functional impairment in the activities of the patient’s daily living.

- On the basis of diagnostic procedures, the disorder in question must be unequivocally attributed to a neurodegenerative process.

Whether or not PPA and other aphasias are the only source of cognitive impairment in a patient is often difficult to assess because: 1) as with other neurologically degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease, there are currently no reliable non-invasive diagnostic tests for aphasias, and thus neuropsychological assessments are the only tool physicians have for diagnosing patients; and 2) aphasias often affect other, non-language portions of these neuropsychological tests, such as those specific for memory.[1]

Risk factors

There have been no large epidemiological studies on the incidence and prevalence of the PPA variants. Though it most likely has been underestimated, onset of PPA has been found to occur in the sixth or seventh decade.[9]

There are no known environmental risk factors for the progressive aphasias. However, one observational, retrospective study suggested that vasectomy could be a risk factor for PPA in men.[12] These results have yet to be replicated or demonstrated by prospective studies.

PPA is not considered a hereditary disease. However, relatives of a person with any form of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, including PPA, are at slightly greater risk of developing PPA or another form of the condition.[13] In a quarter of patients diagnosed with PPA, there is a family history of PPA or one of the other disorders in the FTLD spectrum of disorders. It has been found that genetic predisposition varies among the different PPA variants, with PNFA being more commonly familial in nature than LPA or SD.[9]

The most convincing genetic basis of PPA has been found to be a mutation in the GRN gene.[14] Most patients with observed GRN mutations present clinical features of PNFA, but the phenotype can be atypical.[11]

Treatment

Due to the progressive, continuous nature of the disease, improvement over time seldom occurs in patients with PPA as it often does in patients with aphasias caused by trauma to the brain.[1]

In terms of medical approaches to treating PPA, there are currently no drugs specifically used for patients with PPA, nor are there any specifically designed interventions for PPA. A large reason for this is the limited research that has been done on this disease. However, in some cases, patients with PPA are prescribed the same drugs Alzheimer's patients are normally prescribed.[1]

The primary approach to treating PPA has been with behavioral treatment, with the hope that these methods can provide new ways for patients to communicate in order to compensate for their deteriorated abilities.[1] Speech therapy can assist an individual with strategies to overcome difficulties. There are three very broad categories of therapy interventions for aphasia: restorative therapy approaches, compensatory therapy approaches, and social therapy approaches.[15] Rapid and sustained improvement in speech and dementia in a patient with primary progressive aphasia utilizing off-label perispinal etanercept, an anti-TNF treatment strategy also used for Alzheimer's, has been reported.[16] A video depicting the patient's improvement was published in conjunction with the print article.[17] These findings have not been independently replicated and remain controversial.

Causes

Currently, the specific causes for PPA and other degenerative brain disease similar to PPA are unknown. Autopsies have revealed a variety of brain abnormalities in people who had PPA. These autopsies, as well as imaging techniques such as CT scans, MRI, EEG, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET), have generally revealed abnormalities to be almost exclusively in the left hemisphere.[1]

Notable individuals affected

On September 23, 2016, it was reported that Terry Jones of Monty Python had been diagnosed with the condition.[18][19]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Primary Progressive Aphasia - National Aphasia Association". National Aphasia Association. Retrieved 2017-12-17.

- ↑ Mesulam M (1982). "Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia". Annals of Neurology. 11 (6): 592–8. doi:10.1002/ana.410110607. PMID 7114808.

- ↑ Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. (March 2011). "Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants". Neurology. 76 (11): 1006–14. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. PMC 3059138. PMID 21325651.

- ↑ Bonner MF, Ash S, Grossman M (November 2010). "The new classification of primary progressive aphasia into semantic, logopenic, or nonfluent/agrammatic variants". Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 10 (6): 484–90. doi:10.1007/s11910-010-0140-4. PMC 2963791. PMID 20809401.

- ↑ Harciarek M, Kertesz A (September 2011). "Primary progressive aphasias and their contribution to the contemporary knowledge about the brain-language relationship". Neuropsychol Rev. 21 (3): 271–87. doi:10.1007/s11065-011-9175-9. PMC 3158975. PMID 21809067.

- ↑ Mesulam MM (April 2001). "Primary progressive aphasia". Annals of Neurology. 49 (4): 425–32. doi:10.1002/ana.91. PMID 11310619.

- ↑ Adlam AL, Patterson K, Rogers TT, et al. (Nov 2006). "Semantic dementia and fluent primary progressive aphasia: two sides of the same coin?". Brain. 129 (Pt 11): 3066–80. doi:10.1093/brain/awl285. PMID 17071925.

- ↑ Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. (Mar 2004). "Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia". Annals of Neurology. 55 (3): 335–46. doi:10.1002/ana.10825. PMC 2362399. PMID 14991811.

- 1 2 3 Husain, Masud; Schott, Jonathan M. (2016). Oxford Textbook of Cognitive Neurology and Dementia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199655946.

- ↑ Mesulam MM: Primary progressive aphasia—a language-based dementia. N Engl J Med 2003, 349:1535–1542

- 1 2 Dickerson, Bradford C. (2016-05-19). Hodges' Frontotemporal Dementia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107086630.

- ↑ Weintraub S, Fahey C, Johnson N, et al. (December 2006). "Vasectomy in men with primary progressive aphasia". Cogn Behav Neurol 19 (4): 190–3. doi:10.1097/01.wnn.0000213923.48632.ab. PMID 17159614.

- ↑ Goldman JS, Farmer JM, Wood EM, et al. (Dec 2005). "Comparison of family histories in FTLD subtypes and related tauopathies". Neurology. 65 (11): 1817–9. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000187068.92184.63. PMID 16344531.

- ↑ Spinelli, E. G., Mandelli, M. L., Miller, Z. A., Santos-Santos, M. A., Wilson, S. M., Agosta, F., Grinberg, L. T., Huang, E. J., Trojanowski, J. Q., Meyer, M., Henry, M. L., Comi, G., Rabinovici, G., Rosen, H. J., Filippi, M., Miller, B. L., Seeley, W. W. and Gorno-Tempini, M. L. (2017), Typical and atypical pathology in primary progressive aphasia variants. Ann Neurol., 81: 430–443. doi:10.1002/ana.24885

- ↑ Manasco, H. (2014). The Aphasias. In Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders (Vol. 1, p. 91). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- ↑ Tobinick E (2008). "Perispinal etanercept produces rapid improvement in primary progressive aphasia: identification of a novel, rapidly reversible TNF-mediated pathophysiologic mechanism". Medscape Journal of Medicine. 10 (6): 135. PMC 2491668. PMID 18679537.

- ↑ Tobinick, Edward (10 June 2008). "Video 1". Medscape J Med. 10 (6): 135. PMC 2491668. PMID 18679537.

- ↑ "Monty Python's Terry Jones diagnosed with dementia". BBC.com. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

The news was confirmed as Bafta Cymru announced the Welsh-born comedian is to be honoured with an outstanding contribution award.

- ↑ "Terry Jones, of Monty Python fame, diagnosed with dementia". 23 September 2016.

Further reading

- Amici S, Ogar J, Brambati SM, et al. (Dec 2007). "Performance in specific language tasks correlates with regional volume changes in progressive aphasia". Cognitive & Behavioral Neurology. 20 (4): 203–11. doi:10.1097/WNN.0b013e31815e6265. PMID 18091068.

- Gliebus G (March 2010). "Primary progressive aphasia: clinical, imaging, and neuropathological findings". Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 25 (2): 125–7. doi:10.1177/1533317509356691. PMID 20124255.

- Henry ML, Beeson PM, Alexander GE, Rapcsak SZ (February 2012). "Written language impairments in primary progressive aphasia: a reflection of damage to central semantic and phonological processes". J Cogn Neurosci. 24 (2): 261–75. doi:10.1162/jocn_a_00153. PMC 3307525. PMID 22004048.

- Henry ML, Gorno-Tempini ML (December 2010). "The logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia". Current Opinion in Neurology. 23 (6): 633–7. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833fb93e. PMC 3201824. PMID 20852419.

- Reilly J, Rodriguez AD, Lamy M, Neils-Strunjas J (2010). "Cognition, language, and clinical pathological features of non-Alzheimer's dementias: an overview". J Commun Disord. 43 (5): 438–52. doi:10.1016/j.jcomdis.2010.04.011. PMC 2922444. PMID 20493496.

- Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD (January 2008). "Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias". Brain. 131 (Pt 1): 8–38. doi:10.1093/brain/awm251. PMC 2373641. PMID 17947337.

External links

- FAQ on PPA from IMPPACT, the International PPA Connection

- PPA information from the UCSF Memory and Aging Center

- Northwestern Cognitive Neurology and Alzheimer's Disease Center

- Primary Progressive Aphasia Support Group (Facebook)