Andalusian Arabic

| Andalusian Arabic | |

|---|---|

| عربية أندلسية | |

| Native to | formerly Al-Andalus (modern-day Spain and Portugal) |

| Era | 9th–17th century |

| Arabic alphabet (Maghrebi script) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

xaa |

xaa | |

| Glottolog |

anda1287[1] |

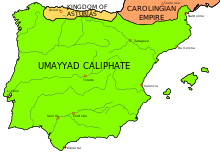

Al-Andalus in 750 A.D. | |

Andalusian Arabic, also known as Andalusi Arabic, was a variety or varieties of the Arabic language spoken in Al-Andalus, the regions of the Iberian Peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal) under Muslim rule (and for some time after) from the 9th century to the 17th century. It became an extinct language in Iberia after the expulsion of the Moriscos, which took place over a century after the Conquest of Granada by Christian Spain. Once widely spoken in Iberia, the expulsions and persecutions of Arabic speakers caused an abrupt end to the language's use on the peninsula. Its use continued to some degree in Africa after the expulsion although Andalusi speakers were rapidly assimilated by the Moroccan and Tunisian communities to which they fled.

Andalusi Arabic is still used in Andalusi music and has significantly influenced the dialects of such towns as Sfax in Tunisia, Fez, Rabat, Nedroma, Tlemcen, Blida, Cherchell,.[2] It is still used by communities of the descendants of Moriscos (Andalusi Muslims) in cities like Tangier and Tetouan in Morocco and Testour, Ghar al Milh and Sfax in Tunisia which welcomed Moriscos refugees. It also exerted some influence on Mozarabic, Spanish (particularly Andalusian), Ladino, Catalan, Portuguese, Classical Arabic and the Moroccan, Tunisian, Hassani and Algerian Arabic dialects.

Andalusian Arabic appears to have spread rapidly and been in general oral use in most parts of Al-Andalus between the 9th and 15th centuries. The number of speakers is estimated to have peaked at around 5–7 million speakers around the 11th and 12th centuries before dwindling as a consequence of the Reconquista, the gradual but relentless takeover by the Christians. In 1502, the Muslims of Granada were forced to choose between conversion and exile; those who converted became known as the Moriscos. In 1526, this requirement was extended to the Muslims elsewhere in Spain (Mudéjars). In 1567, Philip II of Spain issued a royal decree in Spain forbidding Moriscos from the use of Arabic on all occasions, formal and informal, speaking and writing. Using Arabic in any sense of the word would be regarded as a crime. They were given three years to learn a "Christian" language, after which they would have to get rid of all Arabic written material. This triggered one of the largest Morisco Revolts. Still, Andalusian Arabic remained in use in certain areas of Spain until the final expulsion of the Moriscos at the beginning of the 17th century.[3]

As in every other Arabic-speaking land, native speakers of Andalusian Arabic were diglossic, that is, they spoke their local dialect in all low-register situations, but only Classical Arabic was resorted to when a high register was required and for written purposes as well.

Andalusian Arabic belongs to Early Western Neo-Arabic, which does not allow for any separation between Bedouin, urban, or rural dialects, nor does it show any detectable difference between communal dialects, such as Muslim, Christian and Jewish.

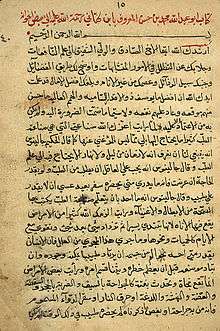

The oldest evidence of Andalusian Arabic utterances can be dated from the 10th and 11th century, in isolated quotes, both in prose and stanzaic Classical Andalusi poems (muwashahat), and then, from the 11th century on, in stanzaic dialectal poems (zajal) and dialectal proverb collections, while its last documents are a few business records and one letter written at the beginning of the 17th century in Valencia.

Features of Andalusian Arabic

Many features of Andalusian Arabic have been reconstructed by Arabists using Hispano-Arabic texts (such as the azjâl of Ibn Quzmân, Shushtari and others) composed in Arabic with varying degrees of deviation from classical norms, augmented by further information from the manner in which the Arabic script was used to transliterate Romance words. Such features include the following.

Phonology

The phoneme represented by the letter ق in texts is a point of contention. The letter, which in Classical Arabic represented either a voiceless pharyngealized velar stop or a voiceless uvular stop, most likely represented some kind of post-alveolar affricate or velar plosive in Andalusian Arabic.

The vowel system was subject to a heavy amount of fronting and raising, a phenomenon known as imāla, causing /a(ː)/ to be raised, probably to [ɛ] or [e] and, particularly with short vowels, [ɪ] in certain circumstances, particularly when i-mutation was possible.

Contact with native Romance speakers led to the introduction of the phonemes /p/, /ɡ/ and, possibly, the affricate /tʃ/ from borrowed words.

Monophthongization led to the disappearance of certain diphthongs such as /aw/ and /aj/ which were leveled to /oː/ and /eː/, respectively, though Colin hypothesizes that these diphthongs remained in the more mesolectal registers influenced by the Classical language.

There was a fair amount of compensatory lengthening involved where a loss of consonantal gemination lengthened the preceding vowel, whence the transformation of عشّ /ʕuʃ(ʃ)/ ("nest") into عوش /ʕuːʃ/.

Syntax and morphology

The -an which, in Classical Arabic, marked a noun as indefinite accusative (see nunation), became an indeclinable conjunctive particle, as in Ibn Quzmân's expression rajul-an 'ashîq.

The unconjugated prepositive negative particle lis developed out of the classical verb lays-a.

The derivational morphology of the verbal system was substantially altered. Whence the initial n- on verbs in the first person singular, a feature shared by many Maghrebi dialects. Likewise the form V pattern of tafaʻʻal-a (تَفَعَّلَ) was altered by epenthesis to atfa``al (أتْفَعَّل).

Andalusian Arabic developed a contingent/subjunctive tense (after a protasis with the conditional particle law) consisting of the imperfect (prefix) form of a verb, preceded by either kân or kîn (depending on the register of the speech in question), of which the final -n was normally assimilated by preformatives y- and t-. An example drawn from Ibn Quzmân will illustrate this:

| Example | Transliteration | English translation |

|---|---|---|

لِس كِن تّراني |

lis ki-ttarânî (underlying form: kîn tarânî) law[lower-alpha 1] lâ mâ nânnu ba`ad |

You would not see me if I were not still moaning |

- ↑ The conditional "law" (لَو) is the source of the modern Spanish Ojalá, (law sha Allah; لَوْ شَآءَ ٱللَّهُ).

See also

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Andalusian Arabic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- ↑ Kees Versteegh, et al.: Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, Brill Publishers, 2006.

Bibliography

- Corriente, Frederico (1997), A Dictionary of Andalusi Arabic, New York: Brill

- Singer, Hans-Rudolf (1981), "Zum arabischen Dialekt von Valencia", Oriens, Brill, 27, pp. 317–323, doi:10.2307/1580571, JSTOR 1580571

- Corriente, Frederico (1978), "Los fonemas /p/ /č/ y /g/ en árabe hispánico", Vox Romanica, 37, pp. 214–18