Sotk

Coordinates: 40°12′11″N 45°51′53″E / 40.20306°N 45.86472°E

| Sotk Սոթք | |

|---|---|

Sotk | |

| Coordinates: 40°12′11″N 45°51′53″E / 40.20306°N 45.86472°E | |

| Country | Armenia |

| Marz (Province) | Gegharkunik |

| Founded | 15th century |

| Elevation | 2,032 m (6,667 ft) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • Total | 1,135 |

| Time zone | UTC+4 ( ) |

Sotk (Armenian: Սոթք, until 1991 Zod) is a village in the Gegharkunik Province of Armenia, well known for its gold mines.[1]

Etymology

According to J. Markwart and N. Adonts, the name Sotk may be connected to the name of a tribe called Tsavde (atsvots) mentioned in ancient Armenian sources [2], while others connect it with the toponym Suta (or Shuta) of the Hittite sources [2] (the presence of the Hittites was proposed in the vicinity of Lake Sevan in 2009[3]).

History

Sotk has been well known for its mines throughout its history. The mines may have been exploited as early as the 2nd millennium BC, evidenced by the discovery of pits, funnels covered with grass, underground workings, wooden tools, stone mortars, washing pots, and more. The mines were used with interruptions until the 14th century AD, and later rediscovered in the 20th century.[4]

Bronze Age

Materials, cemeteries, weapons, bones, and everyday life objects, belonging to the early Bronze Age, have been found in complexes of settlements around the Sotk mountain pass[5]. During this time, gold may have been acquired by alluvial way, while real mining may have begun in the later bronze age.[6]

On the southern slope of the mine, ruins of a large ancient settlement are visible, from where a grass-covered path led to the mine (in 1954, this path would be turned into a road for miners). The river valley is covered by artificial oval terraces which steep from the side towards the river flow.[4] West of Sotk, around the nearby town of modern Vardenis, are some cyclopean fortresses, with corresponding cemeteries from the 2nd and 1st millennium BC, among which is Tsovak, where there is a cuneiform inscription by Urartian king Sarduri II. To the north is a settlement of the Kura-Araxes culture. Many other such ruins can be found near Sotk, such as in Chambarak, indicating the Sevan Lake basin was a significant region, controlled from centers like Lchashen by confederations of chiefdoms, such as the Uduri-Etiuni mentioned in Urartian sources. Elite tombs in Lchashen were rich with gold, which, according to metallurgical analyses, would have derived from Sotk.[7]

Antiquity to Middle Ages

At some point during the late Iron Age, the highlands known as "Urartu" became known as "Armenia" (see Urartu § Fall). As the first Armenian political entity expanded eastwards, the regions around Sotk were incorporated as core regions of ancient Armenia.

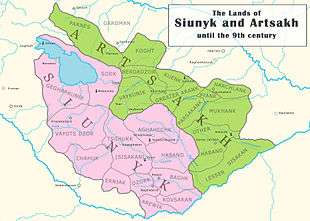

During Antiquity and the Middle Ages, Sotk was part of Syunik, one of the regions of the ancient and the medieval kingdoms of Armenia, where it served as the capital of the region of the same name. Its location on the mountain pass was at a strategic point on the medieval Dvin-Partav road, connecting the southern and eastern regions of the South Caucasus.[4]

Today, the town has a ruined Armenian basilica church said to date from the 7th century, with 13th century gravestones in its walls.

Modern Age

At the end of the nineteenth century, Zod was a village with 1100 Azeri inhabitants, who were then referred to as Tatars.[8] It grew into a town during the region's industrialization in the 1960s and 1970s, primarily due to the exploitation of the Zod gold mines.[9] The town was mostly populated by ethnic Azeris until 1988, when they fled to Azerbaijan as a result of ethnic clashes. The refugees from Zod founded the village of Yeni Zod ("New Zod") in the Goygol District of Azerbaijan.[10]

There is now a gold mine and a light metallurgy fabrication in the outskirts of the town.

Famous people from the town

- Prof. Dr. Ahliman Amiraslanov - Oncologist, Rector of Azerbaijan Medical University[11][12]

- Hafiz Hajiyev - Chairman of Modern Musavat Party in Azerbaijan, Presidential candidate in 2003 and in 2008, former CEO of "Azerfish" State Concern [13]

- Etibar Hajiyev (1971–92) - National Hero of Azerbaijan [14]

See also

References

- ↑ Kiesling, Brady; Kojian, Raffi (2005). Rediscovering Armenia: Guide (2nd ed.). Yerevan: Matit Graphic Design Studio. p. 82. ISBN 99941-0-121-8.

- 1 2 Hakobyan T.Ch., Melik-Bakhshyan S.T., Barseghyan H.Ch., Hayastani ev harakits shrjanneri teghanunneri bararan (Toponymical Dictionary of Armenia and Surrounding Regions), v. 2, 313, Yerevan, 1988-2001.

- ↑ Petrosyan A., The ‘Eastern Hittites’ in the South and East of the Armenian Highland? Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies IV/1 (2009), pp. 63-72

- 1 2 3 Aram Gevorgyan, Arsen Bobokhyan "METALLURGY OF ANCIENT ARMENIA IN CULTURAL AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT", Armenian National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved on 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Xnkikyan O.S. (1977). Arhestnery bronzedaryan Hayastanum (Crafts in Bronze Age Armenia). Yerevan. p. 14.

- ↑ Gevorgyan A., Zalibekyan М. (2007). Kalantaryan. p. 30.

- ↑ Xnkikyan O.S. (1977). Arhestnery bronzedaryan Hayastanum (Crafts in Bronze Age Armenia). Yerevan. p. 18.

- ↑ Article "Зод", Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary (in Russian)

- ↑ SOVIET GOLD POLICY (S-09110), 16 December 1975, CIA De-Classified reports, accessed on 09.12.2009

- ↑ State Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan for Affairs of Refugees and IDPs: on visit of President of Azerbaijan to Yeni Zod village on 4 March 2008 (in Azerbaijani)

- ↑ Web site of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Azerbaijan International Journal

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Decree No 6 of 23 June 1992 the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan: Legislative database of Azerbaijan

- Sotk at GEOnet Names Server

- World Gazeteer: Armenia – World-Gazetteer.com

- Report of the results of the 2001 Armenian Census, National Statistical Service of the Republic of Armenia

- Brady Kiesling, Rediscovering Armenia, p. 82; original archived at Archive.org, and current version online on Armeniapedia.org.