Somerville College, Oxford

| Somerville College | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) Blazon: Argent, three mullets in chevron reversed gules, between six crosses crosslet fitched sable. | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

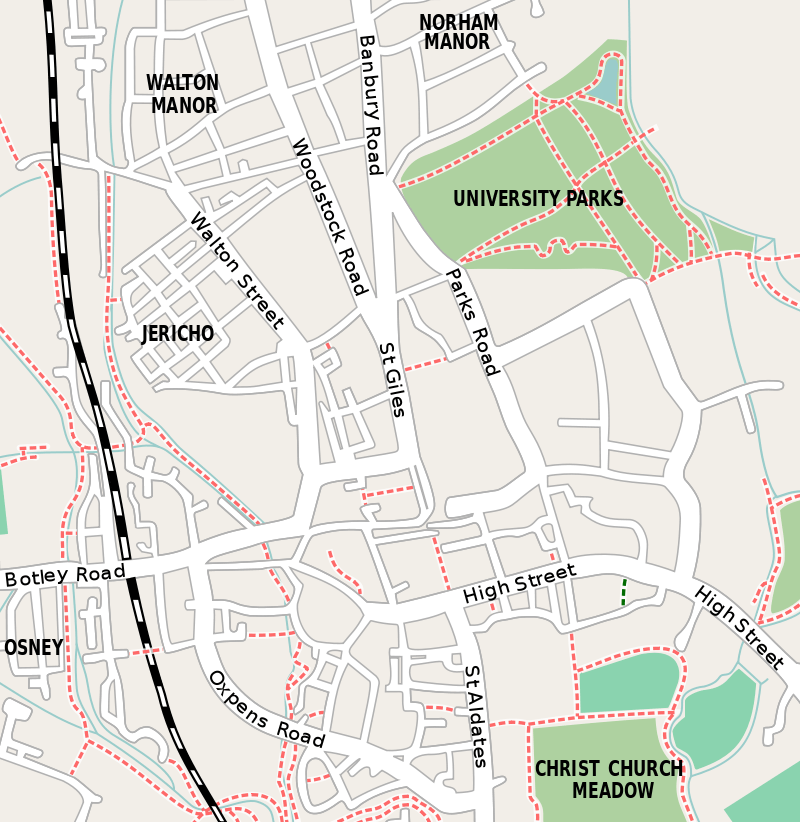

| Location | Woodstock Road, Oxford | |||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′33″N 1°15′44″W / 51.759044°N 1.262272°WCoordinates: 51°45′33″N 1°15′44″W / 51.759044°N 1.262272°W | |||||||||||||||||

| Motto |

Donec rursus impleat orbem (translated: Until it should fill the world again) | |||||||||||||||||

| Established | 1879 | |||||||||||||||||

| Named for | Mary Somerville | |||||||||||||||||

| Previous names | Somerville Hall (1879–1894) | |||||||||||||||||

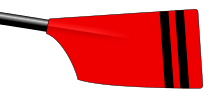

| Colours | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sister college | Girton College, Cambridge | |||||||||||||||||

| Principal | Baroness Royall of Blaisdon | |||||||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 413[1] (2017/2018) | |||||||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 191 | |||||||||||||||||

| Website |

www | |||||||||||||||||

| Boat club | Somerville College Boat Club | |||||||||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||||||||

Location in Oxford city centre | ||||||||||||||||||

Somerville College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. The college has an excellent reputation and an outstanding student satisfaction among the Oxford colleges.[2] Founded in 1879 as Somerville Hall, it was one of the first two women's colleges in Oxford, and its alumni, such as Margaret Thatcher, Indira Gandhi, Dorothy Hodgkin, Vera Brittain, Cornelia Sorabji, Dorothy L. Sayers and many activists, have played a very important role in feminism.[3][4] Today, around 50% of students are male.[5][6]

Somerville has the second biggest college library in Oxford and is known for its friendly and liberal atmosphere, varied architecture and excellent hall food.[7][8][9][10][11] Its liberal character traces back to its foundation by social liberals as the first non-denominational college in Oxford, deliberately unlike the strictly Anglican Lady Margaret Hall, the other women's college opened in the same year.[12] Somerville is the only Oxford college where students may walk on the grass and in 1964, Somerville became one of the first colleges to abandon the policy of locking its gates at night to prevent students staying out late.[13][14] No gowns are worn during Formal Halls.

The current principal is Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, who succeeded Alice Prochaska in 2017.[15] Between 2006 and 2017, the financial endowment rose from £44.5 million[16] to £73.4 million.[17]

The college is located in the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter and Jericho, at the southern end of Woodstock Road, with Little Clarendon Street to the south and Walton Street to the west. It is near the Science Area, Oxford University Press, Radcliffe Observatory, and Blavatnik School of Government and between the University Parks and Port Meadow. It is located nearby the colleges Green Templeton College, Keble College and St Anne's College and the PPH St Benet's Hall.

Somerville is one of only three Oxford colleges to provide on-site accommodation for all undergraduates throughout their course.[9][18] The college is home to circa 600 students,[1] of which more than a third are international.[19] More than half of the UK students admitted to Somerville are educated at state schools, which is close to the university average.[20]

Its sister college is Girton College, Cambridge, which was, like Somerville, one of England's first residential colleges for women.[21]

History

Founding

In June 1878, the Association for the Higher Education of Women was formed, aiming for the eventual creation of a college for women in Oxford. Some of the more prominent members of the association were George Granville Bradley, Master of University College, T. H. Green, a prominent liberal philosopher and Fellow of Balliol College, and Edward Stuart Talbot, Warden of Keble College. Talbot insisted on a specifically Anglican institution, which was unacceptable to most of the other members. The two parties eventually split, and Talbot's group (the "Christ Church camp") founded Lady Margaret Hall, which opened its doors for students in 1879, the same year as Somerville did.[22]

Thus, in 1879, a second committee was formed to create a college "in which no distinction will be made between students on the ground of their belonging to different religious denominations."[lower-alpha 1][23] This committee was called the "Balliol camp" and had close ties to the Liberal Party.[24][25] This second committee included John Percival, George William Kitchin, A. H. D. Acland, Thomas Hill Green, Mary Ward,[26] William Sidgwick, Henry Nettleship, Walter Pater and A. G. Vernon Harcourt.[25]

This new effort resulted in the founding of Somerville Hall, named for the then recently deceased Scottish mathematician and renowned scientific writer Mary Somerville.[22] It was felt that the name would reflect the virtues of liberalism and academic success which the college wished to embody.[27] She was admired by the founders of the college as a scholar, as well as for her religious and political views, including her conviction that women should have equality in terms of suffrage and access to education.

Madeleine Shaw Lefevre was chosen as the first Principal because, although not a well-known academic at the time, her background was felt to reflect the college's political stance.[28] Because of its status as both women's college and non-denominational institution, Somerville was widely regarded within Oxford as "an eccentric and somewhat alarming institution."[29]

Women's college

When opened, Somerville Hall had twelve students, ranging in age between 17 and 36.[30] The first 21 students from Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall attended lectures in rooms above an Oxford baker's shop on Little Clarendon Street.[31] Just two of the original 12 students admitted in 1879 remained in Oxford for three years, the period for which male students had to remain to complete a bachelor's degree.[32]

Increasingly, however, as the college admitted more students, it became more formalized. Somerville appointed its first in-house tutor in 1892 and, by the end of the 1890s, female students were permitted to attend lectures in almost all colleges.[33] In 1891 it became the first women's hall to introduce entrance exams and in 1894 the first of the five women's halls of residence to adopt the title of 'college' (changing its name to Somerville College),[34] the first of them to appoint its own teaching staff, and the first to build a library.[35] In Oxford legend it soon became known as the 'bluestocking college', its excellent examination results refuting the widespread belief that women were incapable of high academic achievement.[35]

In the 1910s, Somerville became known for its support for the women's suffrage campaign.[4] In 1920, Oxford University allowed women to matriculate and therefore gain degrees.[36][37] All female students had to be chaperoned when in the presence of male students from the college's inception. The practice was abolished in 1925, although male visitors to the college were still subject to a curfew.[38] In 1925, during the principalship of Janet Vaughan, Somerville's college charter was granted.

World War One

During World War I the college was converted into a military hospital as Somerville Section of the 3rd Southern General Hospital, adjacent to the Radcliffe Infirmary.[39] For the duration of the war, Somerville students relocated to Oriel College.[4] Because many male students had left Oxford to enlist in the military, Somerville was able to rent St Mary Hall Quad which they bricked off from the rest of the college to segregate it from the Oriel's remaining male students.[40] Many students and tutors were involved in work in World War I and some of them went to the Western Front in France.

Notable patients who stayed in Somerville include Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon. Graves and Sassoon were both to reminisce of their time at Somerville Hospital. How unlike you to crib my idea of going to the Ladies' College at Oxford, Sassoon wrote to Graves in 1917, and called it very much like Paradise. At Somerville College, Graves met his first love, a nurse and professional pianist called Marjorie. About his time at Somerville, he wrote: I enjoyed my stay at Somerville. The sun shone, and the discipline was easy. Officer Llewelyn Davies died at the college. Photographs of the college in this period can be found hanging in Hall, outside the pantry.

Once the war ended, the return to normality between Oriel College and Somerville College was delayed, sparking both frustration and an incident in spring 1919 known as the 'Oriel raid', in which male students made a hole in the wall dividing the sexes. In July 1919 the Principal (Emily Penrose) and Fellows returned to Somerville.

Alumna Vera Brittain wrote about the impact of the war in Oxford and paid tribute to the work of the Principal, Miss Penrose, in her memoir Testament of Youth.

Admission of men

Starting in the 1970s, the traditionally all-male colleges in Oxford began to admit female students.[41] Since it was assumed that recruiting from a wider demographic would guarantee better students, there was pressure on single-sex colleges to change their policy to avoid falling down the rankings.[42] All-female colleges, like Somerville, found it increasingly difficult to attract good applicants and fell to the bottom of the intercollegiate academic rankings during the period.[43]

During the 1980s, there was much debate as to whether women's colleges should become mixed. Somerville remained a women's college until 1992, when its statutes were amended to permit male students and fellows; the first male fellows were appointed in 1993, and the first male students admitted in 1994.[44][45] Somerville became the second-last college (after St Hilda's) to become coeducational.[46] With an intake 50% male/female; a gender balance maintained to this day, though without formal quotas.

In the 1890s Somerville helped fashion the "New Woman"; a century later….the college has set itself the perhaps greater challenge of educating the "New Man."

Buildings and grounds

The college and its main entrance, the Porters' Lodge, are located on Woodstock Road. The front of the college runs between the Oxford Oratory and the Faculty of Philosophy. Somerville has buildings of various architectural styles, many of which bear the names of former principals of the college, located around one of Oxford's biggest quads. Five buildings are Grade II-listed.

A 2017 archaeological evaluation of the site shows that in the medieval period the area now occupied by Somerville lay in fields beyond the boundary of Oxford. There is evidence of a 17th century building and earthworks beneath Somerville's site, some of which almost certainly relates to the defensive network placed around the city by Royalists during the Civil War. There are also remains of some 19th century buildings, including a stone-lined well.[49]

Walton House

The original building of Somerville Hall, Walton House (commonly called 'House') was built in 1826 and purchased from St John's College in 1880 amid fears that the men's colleges might, in the future, repossess the site for their own purposes.[30] The house could only accommodate 7 of the 12 students who came up to Oxford in the first year.[50] In 1881, Sir Thomas Graham Jackson was commissioned to build a new south wing which could accommodate eleven more students. In 1892, Walter Cave added a north wing and an extra storey. He also installed a gatehouse at the Woodstock Road entrance. In 1897/98, the 'Eleanor Smith cottages' were built, adjoining Walton House.[51]

Today House is home to some students. It also contains Green Hall, where guests to College are often greeted and in which prospective students are registered and wait for interviews. Until 2014, it housed the college bar. Most of the administration of college and academic pigeon-hole messageboxes are located in House. A staircase from Green Hall leads up to Hall. Somerville's dining hall has a curved ceiling and wooden panelling and is one of very few in Oxford to contain portraits only of women.

Park

Originally known as West, due to its location within the college, the project to build a second self-contained hall was an attempt to imitate Newnham College, Cambridge. The building was designed by Harry Wilkinson Moore and built in two stages. The 1885-7 phase saw the construction of rooms for 18 students with their own dining-room, sitting rooms and Vice-Principal. This was a deliberate policy aimed at replicating the family environment that the women students had left.[51] This arrangement had the effect of turning House and West into rivals.[52] The second building stage (1888-1895) created two sets of tutors' rooms, a further 19 rooms and the West Lodge (now Park Lodge).[50] It was renamed Park in honour of Daphne Park, the Principal from 1980 to 1989.

There are over 60 student rooms and Fellows' rooms within the building. There is a music room and computer room. Park is a Grade II-listed building.[53]

Library

Designed by Basil Champneys in 1903 and opened by John Morley the following year, Somerville College Library was the first purpose-built library amongst the women's colleges of the university. Specially for this opening, Demeter was written by Robert Bridges and performed for the first time. As such it was designed to serve readers beyond the membership of the college and to contain 60,000 volumes despite the college only possessing 6000 in 1903. The Grade II-listed building now contains around 120,000 items and is the second largest college library in the university.

Amelia Edwards, John Stuart Mill, John Ruskin and Vera Brittain are notable benefactors to the library.[54]

The John Stuart Mill room contains what was Mill's personal library in London at the time of his death, with significant annotations in many of the books.[55]

The library dominates the north wing of the main quadrangle and is open 24 hours, with wifi access which is college-wide, a group study room, and many computers. It has with 100% the highest library satisfaction according to the annual student surveys.[56]

Hall and Maitland

Until 1911, there was no hall large enough to seat the entire college. The buildings were designed by Edmund Fisher in Queen Anne style and Edwardian Baroque architecture. Maitland Hall and Maitland were opened by H. A. L. Fisher, the Vice-Chancellor of the University and Gilbert Murray.[57] Murray, whose translations of Greek drama were performed at Somerville in 1912 and 1946, supported Somerville in many ways, including endowing its first research fellowship. A fund was raised as a memorial to Miss Maitland, the principal of Somerville Hall (College from 1894) from 1889 to 1906. This money was used to pay for the oak panelling in Hall. The panelling of the south wall was specially designed to frame the portrait of Mary Somerville by John Jackson.[58] The buildings were constructed on the site of an adjoining building gifted to Somerville by E. J. Forester in 1897 and bought from University and Balliol Colleges for £4000 and £1,400.[50] There was difficulty in the construction of the buildings, which is now thought to have been the result of the outer limit of the Oxford city fortifications running under the site. In 1935, Morley Horder reconstructed the archway which connected Maitland Hall and the south wing of Walton House. In 1947, André Gide gave a lecture in the hall.[57]

Hall and Maitland form the East face of the main quad and are Grade II-listed buildings.[59] The Senior Common Room is situated on the ground floor. The first floor is occupied by the pantry and the hall, in which Formal Hall (called guest night) is held weekly during term time.

Maitland houses few students, being mainly occupied by Fellows' offices and the college IT office. The building is named after Principal Agnes Maitland, and is to the south of Hall.[60]

Penrose

The Penrose block was designed by Harold Rogers in 1925 and its first students were installed in 1927. It is situated at the south western end of the main quadrangle on the site of 119 and 119A Walton Street.[50] A row of poplars had to be removed in 1926 for the construction of Penrose.[61]

The building was refurbished in 2014, with carpets replacing the formerly bare wooden floorboards, and new furniture. Penrose is named for Dame Emily Penrose, the third principal of the college. Penrose houses mainly first year accommodation, with around 30 rooms.[60] Some fellows' rooms are located in Penrose.

Darbishire

Darbishire Quad was the culmination of a long-standing project to absorb Woodstock Road properties above the Oxford Oratory. In 1920, three houses (29, 31 and 33) were purchased by the college from the vicar of St Giles' Church, Oxford, for the sum of £1,300. The three properties were constructed in 1859 and had been rented by the college prior to their purchase. The adjoining 'Waggon and Horses' was purchased from St John's College, Oxford, in 1923. These buildings were demolished between 1932 and 1933 together with the old Gate House.

Morley Horder was commissioned to build a quadrangle which would fill the space left by the demolished structures with a loan of £12,000 from Christ Church. The porters' lodge and a council room, the New Council Room, were constructed at the entrance to the quad, which housed undergraduate and fellows' rooms.[50] The coat of arms of Somerville and that of co-founder John Percival, first principal Madeleine Shaw-Lefevre and Helen Darbishire were carved by Edmund Ware inside the quadrangle. The archway leading to Hall was reconstructed in 1938.

Originally it was called the East Quadrangle and it was opened in June 1934 by Lord Halifax, who called it 'a notable addition to buildings of varying styles' (varii generis aedificiia additamentum nobile) in the Creweian Oration during the Encaenia. Darbishire was renamed in 1962 in honour of the principal of the college during its construction, Helen Darbishire.[11]

Today Darbishire contains around 50 student rooms mixed with tutors' offices, the college archive and medical room.[62] The offices of the Global Ocean Commission, co-chaired by José María Figueres, Trevor Manuel and David Miliband, were situated in Darbishire as part of a partnership with Somerville, from 2012 to 2016, when the organisation completed its work.[63]

Darbishire Quad is described on the opening page of Gaudy Night by alumna Dorothy L. Sayers and is home to a clock donated by alumna Eleanor Rathbone.[64]

Chapel

Built largely with funds provided by alumna Emily Georgiana Kemp in 1935, Somerville Chapel reflects the nondenominational principle on which the college was founded in 1879. No religious texts were used for admission and nondenominational Christian prayers were said in college. The chapel's history, architecture, and artworks give valuable insights into the religious, intellectual, and cultural roots of what would subsequently become a global norm. The chapel can be seen as both a manifestation of the aspirations of liberal Christianity in the interwar years, including the advancement of women and ecumenism, and of the contestation of the role of religion in higher education among elites in the same period.[65]

The chapel does not have a chaplain, but a 'Chapel Director' which is in keeping with its undenominational tradition. The chapel provides opportunities for Christian worship in addition to hosting speakers with a multi-faith range of religious perspectives.[66] The chapel also has an excellent mixed-voice choir, the Choir of Somerville College, which tours and produces occasional CDs.[67]

Hostel and Holtby

Hostel is a small block between House and Darbishire, completed in 1950 by Geddes Hyslop.[68] It houses 10 students over three floors. The Bursary is on the ground floor.[60]

Holtby, designed in 1951 and completed in 1956 by Hyslop,[68] is situated above the library extension, adjacent to Park. It has 10 rooms for undergraduates and is named for alumna Winifred Holtby.[62]

Vaughan and Margery Fry & Elizabeth Nuffield House

Designed by Sir Philip Dowson between 1958 and 1966, Vaughan and Margery Fry & Elizabeth Nuffield House (commonly shortened to Margery Fry) are both named for former principals of the college, whilst Elizabeth Nuffield was an important proponent of women's education and along with her husband Lord Nuffield, a financial benefactor of the college. Margery Fry was opened in 1964 by Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit and Vaughan was opened in 1966. Constructed in the same architectural style, with an exterior concrete frame standing away from the walls of the interior edifice, the two buildings sit atop a podium containing shops and an arcaded walkway on Little Clarendon Street.

Vaughan is the larger of the two, with 11 rows to its concrete frame compared to the 8 of Margery Fry.[69] It is a Grade II-listed building.[70] Vaughan contains around 60 undergraduate rooms, which are smaller than those of Margery Fry and house exclusively first year students, along with the junior deans. Vaughan was refurbished in 2013, with new bathroom facilities, including, for the first time, sinks. Beneath the two buildings, a tunnel provides access to Somerville from Little Clarendon Street.[62]

Margery Fry serves as the centre of the post graduate student community at Somerville and contains 24 graduate rooms. Other accommodation for graduate students is provided in buildings adjacent to the College.

Wolfson

Sir Philip Dowson was commissioned to design a building at the back of the college, to house undergraduates and offices for fellows. Wolfson is, in common with Dowson's other work in Somerville, constructed largely of glass and concrete. It is a Grade II-listed building.[69] A four-storey building, with five bays of each floor, Wolfson boasts impressive views of Walton Street from the rear and Somerville's main quadrangle from the front.[62] Wolfson is named for the building's principal benefactor Sir Isaac Wolfson and opened in 1967 by Principal Barbara Craig, with Harold Macmillan, Dorothy Hodgkin and Lord Wolfson giving speeches.[71]

The ground floor of the building contains the Flora Anderson Hall or FAH and the Brittain-Williams Room, named for the college's most famous mother-daughter alumnae. The room was designed in 2012 by Niall McLaughlin Architects and opened on 29 November 2013 by alumna Baroness Shirley Williams during an event which saw her unveil a portrait of herself, which now hangs in the room.[72] The FAH is used for lectures and events. Notably it hosts college parties known as bops.

Margaret Thatcher Centre and Dorothy Hodgkin Quadrangle

Named for the alumna-Prime Minister, the MTC comprises a lobby, lecture room and ante room used for many meetings, with disabled access. The lecture room enjoys AV facilities and can accommodate 60 seated patrons. The venue is used for certain term time events and is popular with conferences.[73] A bust of Margaret Thatcher stands in the lobby, and the meeting room contains portraits of Somerville's two prime-minister alumnae, Margaret Thatcher by Michael Noakes and Indira Gandhi by Sanjay Bhattacharyya.

The Dorothy Hodgkin Quad (DHQ) was conceived in 1985 and completed in 1991.[74] It houses mainly finalists and some second year students. The Quadrangle is above the MTC and designed around self-contained flats of two and four bedrooms with communal kitchens. DHQ is named for Somerville's Nobel Prize winning laureate.[62]

Architect Geoffrey Beard's scheme was submitted to the Oxford City Council in 1986 and energies of Sir Geoffrey Leigh and alumna and former Principal Baroness Daphne Park brought support from around the world. The buildings were opened in 1991 by Margaret Thatcher, Dorothy Hodgkin, Principal Catherine Hughes and College Visitor Baron Roy Jenkins.[75]

St Paul’s Nursery

Somerville College was the first Oxford college to provide a nursery for the children of Fellows and staff and is still one of the few colleges to do so. Alumna Dorothy Hodgkin donated much of her Nobel Prize money to the project.[76] St Paul’s Nursery is also open to families who are not connected with the college and cares for 16 children between the ages of 3 months and 5 years.[77]

Radcliffe Observatory Quarter

ROQ East and West flank the north side of Somerville and overlook the site of the university's principal development, the Blavatnik School of Government. Completed in 2011, the ROQ buildings were the first buildings on the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter and have won 4 awards for their architect Niall McLaughlin. The project was also awarded Oxford City Council's David Steel Sustainable Building Award, being commended for its balancing of Somervillian collegiate heritage with the need for energy efficiency to be a consideration for the new building. Energy efficiency measures include renewable technologies such as solar thermal energy and ground source heat pumps.[78]

The buildings house 68 students and all rooms are en-suite. There are a number of rooms and facilities specifically designed to help those with disabilities, including lifts and adjoining carer rooms. The buildings were made possible by donations of over £2.7 million from over 1000 alumni and friends of the college, and by a significant loan.[62] There is now an unimpeded view of the Observatory.

The Terrace

The most recent construction in Somerville (2013), the college bar in Vaughan replaces the bar in House. The bar is housed in a mainly glass structure, with seating in the college colours of red and black. Following a campaign by the JCR Guinness is now available on tap, and the pool table costs 50p per frame. The college drink, the "Stone-cold Jane Austen", is made from blue VK, Southern Comfort, and Magners cider.[79] Other college drinks are the "Somerville Sunset" and the "College Triple". The college also has its own 'Somerville wine': red, white and sparkling.[80]

Catherine Hughes Building

Named after Somerville's late Principal from 1989 to 1996, the Catherine Hughes Building will be completed in October 2019 and will provide 68 additional bedrooms. The new building, designed by Niall McLaughlin Architects, boasts en suite bathrooms, kitchens and accessible rooms on every floor and a new communal study area for students.[49]

The red brick building will have a frontage on to Walton Street and additional access from the college gardens, aligning with key levels on the adjacent Penrose Building. The bedrooms will be arranged in clusters with kitchens and circulation spaces forming social focal points.

The building's construction has given Somerville sufficient accommodation to allow all students applying from 2017 to live in college for the entirety of their 3 to 4-year undergraduate degree and Somerville is one of only three Oxford colleges able to do so.[9][18]

Gardens

Somerville is the only Oxford college where students may walk on the grass and it has a vast green space behind the unassuming front gate, looked after by two gardeners.[81]

The original site comprised a paddock, an orchard and a vegetable garden and was bounded by large trees. It was home to a donkey, two cows a pony and a pig.[51] The paddock was soon transformed into tennis courts, where huge tents where erected during WWI. During World War Two, large water tanks were dug in the Main Quad and Darbishire Quad, in case or firebombing and the lawns were dug up and planted with vegetables.[61]

In the Main Quad there's a cedar planted by Harold Macmillan in 1976, after an old cedar was victim of a winter storm. Another tree, a Picea likiangensis, was planted in 2007 on the chapel lawn, providing Somerville with an outdoor Christmas tree.[61] The library border of lavender and Agapanthus references the bluestocking reputation of Somerville and the tory blue Ceratostigma willmottianum is planted outside the Margaret Thatcher Centre. Beardtongues, Begonia and 1,200 red and black tulips reflect the college's colours. There are nods to Somerville's long-standing links with India, a strip of Alpine plants in front of Wolfson, a bog garden, herbaceous borders and the emblematic Somerville thistles (Echinops).[81][82][83] The western wall of Penrose and the northern wall of Vaughan form two faces of the Fellows Garden, previously kitchen gardens, which is distinct from the main quad and separated from it by a hedge and a wall. The Fellows Garden is home to a sundial, commissioned in 1926, and a garden roller which was a gift from the parents of tutor Rose Sidgwick.[84]

In 1962, Henry Moore lend his item Falling Warrior to the college and Barbara Hepworth lent Core shortly afterwards. Permanent sculptures in Somerville's garden are made by Wendy Taylor, Friedrich Werthmann and Somervillian Polly Ionides.

Student life

In 2011 student satisfaction was rated in some categories as the highest in the university.[2] Central to the college is its large quad, onto which most accommodation blocks back; it is often filled with students in summer. Somerville is the only Oxford college where students (as opposed to just fellows) may walk on the grass.[13][70] Somerville is sometimes nicknamed The Ville. Formal Halls take place on some Tuesdays and Fridays about six times a term.[85] No gowns are worn and the grace is 'benedictus benedicat'.

Sports

Somerville has a gym situated beneath Vaughan, with treadmills, cross-trainers and weights. Somerville shares a sports ground with Wadham College and St. Hugh's College, on Marston Ferry Road. There are clubs and teams in men's and women's football, rugby (with Corpus Christi), mixed lacrosse, cricket, swimming, hockey, netball, basketball, pool, water polo, tennis, squash, badminton, cycling and croquet.[86][87]

Both the Somerville cricket and netball team won Cuppers for the 2014/15 season.[86][88] The swimming team won Cuppers for the 2015/2016 season.[89]

Rowing

Somerville formed a rowing team in 1921.[90] The college competes in both of the annual university bumps races, Torpids and Summer Eights. The women are the most successful women's rowing team at the University of Oxford, having won the title Head of the River eight times in Summer Eights and five times in Torpids. The club shares the award-winning University College Boathouse on The Isis with St Peter's College, University College and Wolfson College.

Choir

The Choir of Somerville College is mixed voice and is led by the Director of Chapel Music, Will Dawes.[91] In conjunction with the organ scholars, the choir is central to the musical life of the college.

There are regular concerts and cathedral visits as well as recitals featuring soloists from the choir. In recent years the choir has undertaken tours of Germany (2005 and 2009), Italy (2010) and the USA (2014 and 2016).[92] The choir sings every Sunday during term time at the evening service. The organ of the college chapel is a traditionally voiced instrument by Harrison & Harrison.[93]

Somerville offers up to five Choral Exhibitions each year to applicants reading any subject. College Organ Scholars are guaranteed rooms in college for the duration of their course.

The college choir has released two CDs on the Stone Records label, "Requiem Aeternam" (2012)[94] and "Advent Calendar" (2013).[95]

Triennial Ball

Once every three years Somerville hosts a ball which is organised with Jesus College, Oxford. The last ball was held in May 2016 and the next ball will be held in 2019,[96] with a capacity of 1500 people.

The 2013 ball, The Last Ball, was mired in controversy, which was reported in national news. The organisers had intended to display a live nurse shark as entertainment. Permission for the shark was initially granted by principal Alice Prochaska, but was subsequently revoked following student protests. The ball was widely condemned for poor organisation, examples of which included a lack of canapés and the presence of only one food stand, serving pork; the vegetarian options were said to run out quickly and revellers were reportedly set on fire by the pork rotisserie. The Guardian reported 'The ball descended into farce with guests questioning what the organisers had done with the money paid by 1,000 guests.'[97][98][99][100][101][102]

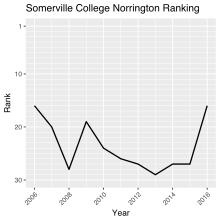

Academic reputation

Before men were admitted to the college, and under the principalship of Barbara Craig, Somerville established a position at, or near the head of the Norrington Table.[103] Currently, by academic performance, Somerville is in the lower half of Oxford University colleges. For the academic year 2016/17, the college came 22nd out of 30 in the Norrington Table, which lists the University's undergraduate colleges in order of their students' examination performances.[104]

University Challenge

Somerville has recently enjoyed success on TV quiz show University Challenge disproportionate to the college's size. The college has won the competition once, triumphing in the University Challenge 2001–02 series and beating Imperial College, London by 200 points to 185. Croatian quizzer Dorjana Širola was one of the contestants.[105] Most recently, the college team reached the final of the University Challenge 2013–14 series, losing in the final to Trinity College, Cambridge, with a score of 134 to 240.[106]

Trinitatis Horribilis 2015

During Trinity term 2015, Somerville was subject to national media coverage as a result of the efforts of principal Alice Prochaska to tackle 'a rise in "excessively harassing and intimidating behaviour" towards female students.'[107] The Daily Telegraph quoted Prochaska as describing 'numerous reports of groping at college parties, rape jokes overheard in communal areas'.[108] The principal wrote in The Guardian of measures taken to address harassment and she expressed her hope that 'a spasm of nastiness among a small minority of students here has been nipped in the bud by the open condemnation of the majority.'[5]

India

Somerville College plays a major role in the relationship between Oxford and India.[109][13] Cornelia Sorabji, who was born in the Bombay Presidency of British India, became the first Indian woman to study at any British university when she came to Somerville in 1889 to study Law[110] and Indira Gandhi, India's first female Prime Minister, studied Modern History at the college in 1937. Radhabai Subbarayan, first woman member of the Indian Council of States (Rajya Sabha) studied at Somerville College as well.[111] Other alumni with links to India include Moon Moon Sen,[112] Agnes de Selincourt,[113] Smit Singh,[114] and Utsa Patnaik.[109] Former Principal Barbara Craig (1967-1980) and fellow Aditi Lahiri were born in Kolkata.

Sonia Gandhi visited Somerville in 2002 and presented a portrait of her late mother-in-law to her alma mater. Indira Gandhi received an honorary degree from the college in 1971.[115]

In 2012, the college and Oxford University announced the creation of a £19m Indira Gandhi Centre for Sustainable Development.[109][116] India provided £3 million and the university and college £5.5 million.[117] The name was later changed to the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development (OICSD).[115] The building will be located at the college.[109][118][119] The OICSD carries out research on sustainable development challenges facing India and provides scholarships for outstanding Indian students.[120] The centre now hosts 12 India scholars.[121]

Somerville's choir will be the first Oxford college choir to tour India.[122]

People associated with Somerville

Alumni

Somervillians include Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and Indira Gandhi, Nobel Prize winning scientist Dorothy Hodgkin, journalist Esther Rantzen, reformer Cornelia Sorabji, writers A. S. Byatt, Vera Brittain, Susan Cooper, Penelope Fitzgerald, Winifred Holtby, Iris Murdoch and Dorothy L. Sayers, politicians Shirley Williams, Margaret Jay and Sam Gyimah, Princess Bamba Sutherland and her sister, philosophers Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley and Onora O'Neill, archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon, actress Moon Moon Sen, soprano Emma Kirkby and numerous (women's rights) activists.

Somerville alumnae have achieved an impressive number of "firsts", both (inter)nationally and at the University of Oxford. The most distinguishable being that of the first woman Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Margaret Thatcher; the first, and only, British woman to win a Nobel Prize in science Dorothy Hodgkin and the first woman to lead the world's largest democracy Indira Gandhi, who was Prime Minister of India for much of the 1970s.

Somerville educated at least twenty-six Dames, fourteen heads of Oxford colleges, ten MP's, ten life peers, four Olympic rowers,[123] three of The 50 greatest British writers since 1945,[124] two prime ministers, two princesses, a queen consort and a Nobel laureate.

Formers students of Somerville belong to an alumni group, the Somerville Association, which was originally founded in 1888.[125]

Fellows

Notable fellows of Somerville College include philosopher G. E. M. Anscombe, classical archaeologist Margarete Bieber, Egyptologist Käte Bosse-Griffiths, biologist Marian Dawkins, classicist Edith Hall, author Alan Hollinghurst, astronomer Chris Lintott, International Federation of University Women founder Rose Sidgwick and botanist Timothy Walker.

Principals

The first principal of Somerville Hall was Madeleine Shaw-Lefèvre (from 1879–1889). The first principal of Somerville College was Agnes Catherine Maitland (1889–1906) when in 1894 it became the first of the five women's halls of residence to adopt the title of 'college', the first of them to appoint its own teaching staff, the first to set an entrance examination, and the first to build a library. She was succeeded by classical scholar Emily Penrose (1906–1926), who established the Mary Somerville Research Fellowship in 1903 which was the first to offer women in Oxford opportunities for research.

The current Principal is Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon who took up the appointment in August 2017, succeeding Alice Prochaska.[15]

Six principals were alumnae of Somerville, two of St Hilda's College.

Coat of arms and motto

Like all Oxford colleges, Somerville has a variety of symbols and colours which are associated with it. The college's colours, which feature on the college scarf and on the blades of its boats, are red and black. The combination was originally adopted in the 1890s.[34] Its flag has the shield from the arms on a yellow background.[126]

The two colours also feature in the college's coat of arms which depicts three mullets in chevron reversed gules, between six crosses crosslet fitched sable. The college's motto is Donec rursus impleat orbem which was originally the motto of the family of Mary Somerville.[34] Her family befriended the new hall, allowing it to adopt their arms and motto.[127] The Latin motto itself is described as "baffling" as, although it translates as "Until It Should Fill the World Again", what the subject of the sentence ("it") is left unspecified.[34] The crest is a hand grasping a crescent and is often omitted.

In popular culture

- The mystery novel Gaudy Night by Dorothy L. Sayers featuring Lord Peter Wimsey is set in Shrewsbury College (a thinly veiled take on Sayers' own Somerville College).[128][129]

- In the 2014 film The Amazing Spider-Man 2 directed by Marc Webb, one of the protagonists, Gwen Stacy, is offered a place to study medicine at Somerville.[130] Its coat of arms is featured in one of the scenes.

- The 2014 biopic Testament of Youth, based on Brittain's memoir of the same name, substituted Merton College, Oxford in the scenes showing Brittain's time as a student at Somerville, arguing that filming in Somerville itself would been too difficult in light of the new buildings constructed there since the film's time period.[131]

- Somerville is the recognisable model for St Bride's College in Michaelmas Term at St Bride's by Brunette Coleman (Philip Larkin).

- In the film Iris from 2001, telling the story of alumna Iris Murdoch and her relationship with John Bayley, Murdoch meets her husband during a dinner at Somerville College.

- In the film The Iron Lady, the young Margaret Thatcher announces her parents that she has won a place at Somerville College.

- Somerville is featured in the BBC series Testament of Youth (1979).

- In de Japanese manga series Master Keaton, the main character married a mathematics student from Somerville College.[132]

- St Jerome's College in Endymion Spring by alumnus Matthew Skelton is based on Somerville College. The cat Mephistopheles is based on the former college cat Pogo.[133]

- Grace Ritchie, the protagonist in Slave Of The Passion by Deirdre Wilson has gone up to Somerville.

Notes

- ↑ Originally LMH only admitted students who were practicing members of the Church of England.[22]

References

- 1 2 "Student statistics". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- 1 2 Tomlin, Jonathan (19 April 2012). "Somerville soars in satisfaction survey".

- ↑ "Somerville and Suffrage". Somerville College. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Adams 1996, p. 78.

- 1 2 How we are fighting sexist laddism and abuse at Somerville College, Oxford, Alice Prochaska, The Guardian, 15 May 2015

- ↑ "Student Statistics - Sex". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ Library & IT

- ↑ Somerville College

- 1 2 3 Somerville College

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 16.

- 1 2 Manuel 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ "True to its Principals". Somerville College. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Patil, Reshma (18 November 2017). "Visa woes: Why Americans, Chinese students outnumber Indians at Oxford Univ". Business Standard.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, p. 669.

- 1 2 "New Somerville Principal announced | University of Oxford". ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ↑ "Oxford College Endowment Incomes, 1973–2006". Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. (updated July 2007)

- ↑ "Financial Statements of the Oxford Colleges (2016–17) | University of Oxford". University of Oxford. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- 1 2 Somerville College website

- ↑ "Student Statistics - nationality". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "4 School Type" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ "Archive of Queens' College Cambridge webpage". archive.org/queens.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 Brockliss 2016, p. 374.

- ↑ Batson 2008, pp. 22-3.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. 21.

- 1 2 Adams 1996, p. 11.

- ↑ "Mary Ward". Somerville College, Oxford. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. 23.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. 25.

- 1 2 Batson 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Frances Lannon (30 October 2008). "Her Oxford". Times Higher Education.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. 28.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, p. 375; 418.

- 1 2 3 4 Adams 1996, p. 47.

- 1 2 Manuel 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Batson 2008, p. xv.

- ↑ Adams 1996, pp. 150-1.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p. 215.

- ↑ "Somerville Hospital – Then and Now". Somerville College. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p. 89.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, p. 572.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, pp. 577-8.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, p. 613.

- ↑ "History of Somerville College, Oxford". Archived from the original on 18 February 2014.

- ↑ Pritchard, Stephen (18 November 1993). "Higher Education: Blue stockings greet blue socks: Somerville College Oxford is preparing to admit its first men next year". The Independent.

- ↑ Brockliss 2016, p. 573.

- ↑ Somerville for Women: An Oxford College 1879–1993, Pauline Adams (Oxford University Press, 1996) ISBN 0-19-920179-X.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- 1 2 "The Catherine Hughes Building". www.some.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Somerville College – British History Online". british-history.ac.uk.

- 1 2 3 Manuel 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 12.

- ↑ "SOMERVILLE COLLEGE, WEST BUILDING". Historic England. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ "John Stuart Mill Collection – Somerville College Oxford". University of Oxford. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ "Library & IT — Somerville College Oxford". some.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- 1 2 Manuel 2013, p. 22.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 19.

- ↑ "Somerville College, Hall and Maltland Block". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 "College Map".

- 1 2 3 Manuel 2013, p. 35.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 http://blogs.some.ox.ac.uk/jcr/accomodation/

- ↑ "contact – Somerville College Oxford". globaloceancommission.org.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ A House of Prayer for all Peoples? The Unique Case of Somerville College Chapel, Oxford 5 March 2018

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ "Home". The Choir of Somerville College, Oxford. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- 1 2 Fair 2014, p. 357.

- 1 2 "Somerville College 1960s, Oxford, UK". manchesterhistory.net.

- 1 2 Haberfield, Catrin (2015). "Somerville should have been your first choice". The Tab.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ "Somerville College – Conference Oxford". conference-oxford.com.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 47.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 48.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 49.

- ↑ "St Paul's Nursery". www.some.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ Cherwell (June 1, 2007). "Drink the bar dry: Worcester, St Hugh's, Sommerville".

- ↑ "Somerville College Wine List". 2014.

- 1 2 Somerville Gardens

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 36.

- ↑ "EVER GREEN – Robert Washington celebrates 30 years at Somerville". www.some.ox.ac.uk. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- ↑ Manuel 2013, p. 29.

- ↑ "Formal Dinners". Somerville College MCR. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- 1 2 "Sports - MCR website". 22 August 2018.

- ↑ "Sports - JCR website". 22 August 2018.

- ↑ Barker, David (16 June 2015). "Somerville defeat Brasenose in thrilling Cricket Cuppers final".

- ↑ "Victory for Somerville at Swimming Cuppers". 9 December 2016.

- ↑ "History – Somerville College Boat Club". scbcrowing.com.

- ↑ "Will Dawes appointed as Director of Chapel Music – Somerville College Oxford". University of Oxford.

- ↑ "Tours". The Choir of Somerville College, Oxford.

- ↑ "The National Pipe Organ Register – NPOR". npor.org.uk.

- ↑ "Milford, Duruflé Requiem Aeternam – Stone Records". classical-iconoclast.blogspot.de.

- ↑ "Advent calendar :: Stone Records, Independent Classical Music". stonerecords.co.uk.

- ↑ "The Somerville-Jesus Surrealism Ball: Enter the Subconscious Mind". 7 June 2016.

- ↑ Sherriff, Lucy (24 April 2013). "Oxford's Somerville College Cancels Student Plans To Display Living Nurse Shark At Summer Ball". HuffPost.

- ↑ Marszal, Andrew (24 April 2013). "Oxford ball scraps shark plans after student protest". The Telegraph.

- ↑ Dufton, Will (13 May 2013). "Review: Somerville-Jesus Ball". The Tab.

- ↑ Poulten, Sarah (23 May 2013). "Somer' Them Say Sorry For Their Balls Up". The Oxford Student.

- ↑ Wright, Nathalie (9 May 2013). "Somerville-Jesus 'Last Ball' goers are "ripped off"". Cherwell.

- ↑ Urquhart, Conal (25 May 2013). "Student ball at Oxford University ends in 'catastrophe'". The Guardian.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 June 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- ↑ "2016-17 Final Norrington Table". ox.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2018-08-10.

- ↑ "University Challenge Series Champions in 2002".

- ↑ "University Challenge, the 2014 final, review: Trinity triumph".

- ↑ Somerville College principal warns of sexual harassment, BBC News, 15 May 2015

- ↑ Oxford chief warns of worrying culture of sexual harassment and groping, The Daily Telegraph, 14 May 2015

- 1 2 3 4 "Somerville's enduring links with India - The Indira Gandhi Centre for Sustainable Development at Somerville College, Oxford". Somerville College, Oxford. 2015.

- ↑ "Becoming a Google Doodle: India's first woman lawyer". Counsel.

- ↑ Pauline Adams (1996). Somerville for women: an Oxford college, 1879-1993. Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0199201792. ,.

- ↑ "Moon Moon Sen Biography". Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ Jane Haggis, Margaret Allen (Spring 2008) Imperial emotions: affective communities of mission in British Protestant women's missionary publications c1880-1920. Journal of Social History 41(3) 691-716

- ↑ "An Event at University of Oxford".

- 1 2 Indira Gandhi’s name dropped from Oxford centre, Hindustan Times, 15 July 2017

- ↑ http://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2012-12-07-indian-government-seed-funds-somerville-centre

- ↑ Indira Gandhi Centre for Sustainable Development at Oxford University approved, The Hindu, 7 December 2012

- ↑ Entwicklungshilfe. Indien steuert Geld für Oxford bei in FAZ of 20 December 2012, page 30

- ↑ India hub in Indira’s old college at Oxford The Telegraph, 30 January 2014

- ↑ "Oxford's "Gateway to India"". The Hindu.

- ↑ "India ties celebrated at House of Lords". www.some.ox.ac.uk. 9 July 2018.

- ↑ "Future Events". www.somervillechoir.com. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ "Oxford at the Olympics". University of Oxford. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ↑ "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945". The Times. 5 January 2008.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p. 43.

- ↑ "Oxford University - Somerville College (England)". www.crwflags.com. 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "Somerville College". Oxford College Archives. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Somerville Stories – Dorothy L Sayers Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine., Somerville College, University of Oxford, UK.

- ↑ Adams 1996, p. 195.

- ↑ The Guardian 2014.

- ↑ The Oxford Student 2015.

- ↑ The absent/present mother, and wife, in Master Keaton

- ↑ A conversation with Matthew Skelton

Bibliography

- Adams, Pauline (1996). Somerville for Women: An Oxford College, 1879-1993. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199201822.

- Manuel, Anne (2013). Breaking New Ground: A History of Somerville College as seen through its Buildings. Oxford: Somerville College.

- Batson, Judy G. (2008). Her Oxford. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1610-7.

- Fair, Alistair (2014). "'Brutalism Among the Ladies': Modern Architecture at Somerville College, Oxford, 1947—67". Architectural History. 57: 357–392. JSTOR 43489754.

- Brockliss, L. W. B. (2016). The University of Oxford: A History. Oxford University Press: Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-924356-3.

Further reading

- Byrne, Muriel St. Clare; Hope Mansfield, Catherine (1922). Somerville College 1879-1921. Oxford: Oxford University Press. OCLC 557727946.

- Salter, H. E.; Lobel, Mary D. (1954). "Somerville College". The Victoria History of the County of Oxford. 3: The University of Oxford. London: British History Online. pp. 343–347.

- Leonardi, Susan J. (1989). Dangerous by degrees : women at Oxford and the Somerville College novelists. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813513669.

- Chapman, Allan (2007). Mary Somerville and the World of Science. Bristol: Canopus. ISBN 9780953786848.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Somerville College, Oxford. |