Corpus Christi College, Oxford

| Corpus Christi College | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford | ||||||

| ||||||

Blazon: see below | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Location | Merton Street | |||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′03″N 1°15′13″W / 51.750909°N 1.253702°WCoordinates: 51°45′03″N 1°15′13″W / 51.750909°N 1.253702°W | |||||

| Full name | The President and Scholars of the College of Corpus Christi in the University of Oxford | |||||

| Established | 1517 | |||||

| Named for | Corpus Christi, Body of Christ | |||||

| Sister college | Corpus Christi College, Cambridge | |||||

| President | Dr Helen Moore (Acting)[1] | |||||

| Undergraduates | 252[2] (December 2017) | |||||

| Postgraduates | 93[2] (December 2017) | |||||

| Website |

www | |||||

| JCR | Corpus Christi JCR | |||||

| MCR | Corpus Christi MCR | |||||

| Boat club | College Boat Club | |||||

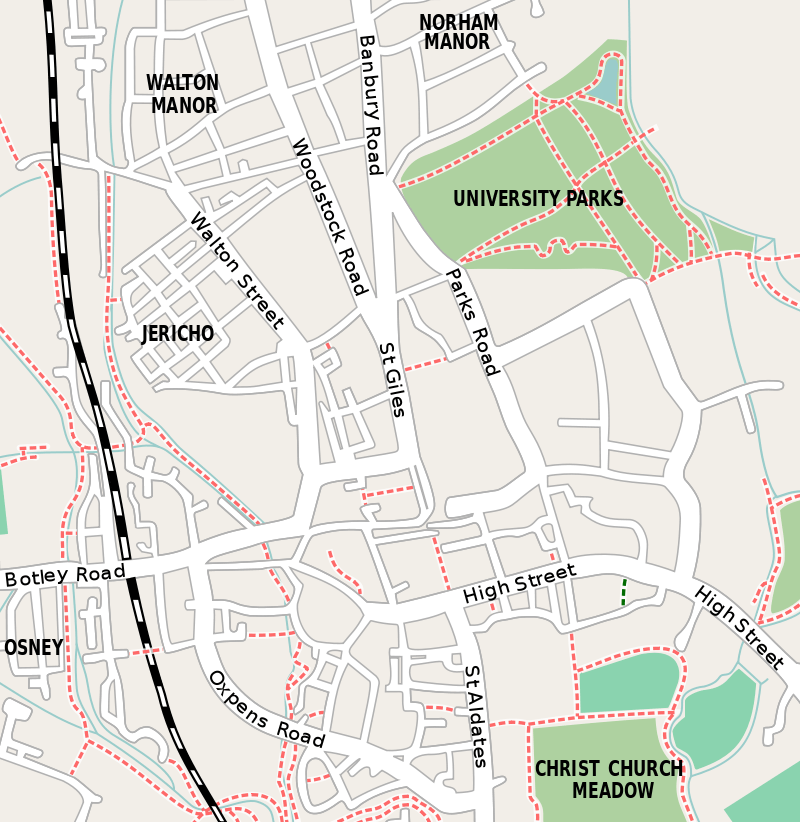

| Map | ||||||

Location in Oxford city centre | ||||||

Corpus Christi College (formally, The President and Scholars of the College of Corpus Christi in the University of Oxford, informally abbreviated as Corpus or CCC), is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1517, it is the 12th oldest college in Oxford, with a financial endowment of £139 million as of 2017.[3]

The college, situated on Merton Street between Merton College and Christ Church, is one of the smallest in Oxford by student population, having around 250 undergraduates and 90 graduates. It is academic by Oxford standards, averaging in the top half of the university's informal ranking system, the Norrington Table, in recent years, and coming second in 2009–10.[4]

The college's role in the translation of the King James Bible is historically significant. The college is also noted for the pillar sundial in the main quadrangle,[5] known as the Pelican Sundial, which was erected in 1581.[6] Corpus achieved notability in more recent years by winning University Challenge on 9 May 2005 and once again on 23 February 2009, although the latter win was later disqualified.[7][8]

The Visitor of the college is ex officio the Bishop of Winchester, currently Tim Dakin.

History

Foundation

Corpus Christi College was founded by Richard Foxe, Bishop of Winchester and accomplished statesman. After joining the church, Foxe worked as a diplomat for Henry Tudor. He became a close confidant of his and, during Henry's reign as Henry VII, was appointed Keeper of the Privy Seal and promoted up the bishoprics, eventually becoming Bishop of Winchester. Throughout this time he was involved in Oxford and Cambridge Universities: he had been Visitor of Magdalen College and of Balliol College, had amended Balliol's statutes for a papal commission, was master of Pembroke College, Cambridge for 12 years and had been involved in the foundation of St John's College, Cambridge, as one of Lady Margaret Beaufort's executors.[9]

Foxe began to build from 1513. He bought a nunnery, two halls, two inns and the Bachelor's Garden of Merton College.[10] The college buildings were probably complete by 1520.[11]

Foxe was assisted in his foundation by his friend Hugh Oldham, Bishop of Exeter, and Oldham's steward, William Frost. Oldham was a patron of education and donated £4,000 and land in Chelsea towards the foundation. For this, he was styled præcipuus benefactor (principal benefactor) by Foxe, remembered in daily prayers and a scholarship was established for students from Lancashire, where Oldham was born.[12][13] Frost bequeathed his estate in Mapledurwell to the college, for which he and wife were remembered in a yearly prayer and a scholarship was founded for his descendants.[14][15]

Foxe was granted letters patent for the foundation by Henry VIII in 1516.[16] The college was officially founded in 1517, when Foxe established the college statutes.[17]

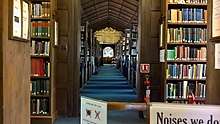

The library of the college was "probably, when completed, the largest and best furnished library then in Europe".[18] The scholar Erasmus noted in a letter of 1519 to the first President, John Claymond, that it was a library "inter praecipua decora Britanniae" ("among the chief beauties of Britain"), and praised it as a "biblioteca trilinguis" ("trilingual library") containing, as it did, books in Latin, Greek and Hebrew.[19]

Founding fellows of the College included Reginald Pole, who would become the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury.[20]

Later developments

In its first hundred years, Corpus hosted leading divines who would lay the foundations of the Anglican Christian identity. John Jewel was Corpus' Reader of Latin, worked to defend a Protestant bent in the Church of England and the Elizabethan Religious Settlement.[21] John Rainolds, elected President in 1598, suggested the idea of the King James Bible and contributed to its text.[22] Richard Hooker, author of the influential Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, was deputy professor of Hebrew.[23]

No one county in England bare three such men (contemporary at large) [Jewel, Rainolds and Hooker] in what college soever they were bred, no college in England bred three such men, in what county soever they were born.

The important Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives taught at Corpus during the 1520s while tutor to Mary Tudor, later Mary I of England.

John Keble, a leader of the Oxford Movement, was an undergraduate at Corpus at the start of the 19th century, and went on to a fellowship at Oriel and to have a college named after him (Keble College, Oxford).

Having been founded nearly half a millennium earlier as a college for men only, Corpus Christi was among many of Oxford's men's colleges to admit its first female students in 1979.[25]

Structures

Buildings

The main buildings on the main college site are the Main Quad, the West Building, the MBI Al Jaber Auditorium, the Fellows' Building, Gentleman-Commoners' Quad and Thomas Quad.

The Main Quad was built for the college's foundation and designed in a late Mediaeval style. The quad was constructed by distinguished builders associated with Henry VIII's Office of Work: master mason William Vertue, master mason William East and carpenter Humphrey Coke (Warden of the Carpenter's Company in London).[26] The quad's architecture later inspired that of Oglethorpe University.[27]

The chapel adjoins the library and is just off the Main Quad. Its location is unusual: many colleges (even small ones) had their chapel in their main quad, with some colleges placing them on the first floor to fit them in (e.g. Lincoln and Brasenose).[28] Its lectern is one of the first bronze eagle lecterns in Oxford; it is the only pre-Reformation one and was a gift of the first president. The chapel's altarpiece is a copy of Ruben's Adoration of the Shepherds, a gift from the antiquarian Sir Richard Worsley.[29][30]

On the corner of Merton Street and Magpie Lane, lie the Jackson and Oldham buildings and Kybald Twychen, which house students. Until the 19th century, town houses took up Magpie Lane. In 1884–85, these houses were torn down and replaced with the New Building and Annexe, which were designed and erected by T. G. Jackson.[31] Jackson's New Building was itself replaced between in the late 1960s with a modernist design by Powell and Moya.[32] Powell and Moya's building uses local limestone rubble, an exposed concrete frame and has the architects' trademark large windows. Great efforts to make the design fit in with the mix of architectures: the plain wall of Oriel College, Merton's Gothic chapel and T. G. Jackson's unrestrained, heavily ornamented Annexe.[33] In 2017, the New Building and Annexe were substantially renovated and renamed the Oldham and Jackson Buildings, respectively.[34]

Corpus also owns several buildings further afield: the Liddell Building on Iffley Road (built with Christ Church in 1991),[34] the Lampl Building (completed in 2014 and named after Sir Peter Lampl)[35] and houses on Banbury Road.

Pelican Sundial

The Pelican Sundial is the large pillar in the centre of Corpus' main quad and dates from 1579. The sundial is named after the gold-painted Pelican on an armillary sphere at the top of the pillar.[36] "Pelican Sundial" is a misnomer, as the pillar contains 27 separate sundials.[37] Nine of the sundials are found easily: four on each face of the square frustum beneath the pelican, four beneath each coat of arms on the cuboid and one facing south on the curved pillar shaft.[38] The remaining sundials are found on the hollows and scallops surrounding the east and west arms. The symbols surrounding the sundials are used to reckon feast days and the signs of the Zodiac.[39] The pillar shaft is covered by three tables: one for calculating the dates of the movable and fixed feasts and the Oxford and legal terms; one being a perpetual calendar and one for finding the time by moonlight.[40]

History and copies

The Pelican Sundial was designed by Charles Turnball and is sometimes called the Turnball Sundial after him. Turnball lived in Corpus for 8 years, reaching the degree of MA.[41] He went on to publish the book A Perfect and Easie Treatise of the Use of the Coelestial Globe in 1585, but it is otherwise unknown what he went on to do.[41]

The Pelican Sundial was not the first sundial at Corpus. Before it was erected, one had been designed for the college by Nicholas Kratzer, an astrologer and horologer for Henry VIII.[42] Like Juan Luis Vives, he was probably one of Cardinal Wolsey's lecturers who resided at Corpus while waiting for the completion of Cardinal College.[43] Kratzer designed many dials, however only three can definitely be attributed to him: fixed ones for the University Church of St Mary the Virgin and Corpus and a portable one for Cardinal Wolsey. Only Wolsey's survives;[lower-alpha 1][45] Kratzer's Corpus dial stood in the garden until around 1706, when the gardens were remodelled for the construction of the Fellows' Building.[46]

The dial has required regular maintenance throughout existence. The markings were replaced were many times over the centuries and, despite restorations overseen by a professor of natural sciences[47] and a historian of science Robert Gunther,[48] more and more errors crept into the pillar's tables. The dial also developed a lean. This was fixed in 1967 after it was discovered that the dial had no solid foundation and that base was made of stone panels loosely packed with rubble.[49] In 1976, the sundial was restored (and its tables corrected) to its state c. 1710 by Philip Pattenden. Since the 1710 tables were designed for the Julian calendar, they have no modern use.[50] The sundial was most recently restored in 2016.[51]

Two copies of the Pelican Sundial exist in America. The first, the Mather Sundial in Princeton University, was commissioned by William Mather as a goodwill gesture between the United Kingdom to the United States.[52] The second is on the front lawn of Pomfret School in Connecticut and was donated in 1912 by the father of a graduating student.[53]

Coat of arms and other symbols

The coat of arms is quite complex, since it incorporates (from left to right) a symbol chosen by the founder, the arms of the See of Winchester, and the arms of Hugh Oldham.

In heraldic terminology: Tierced per pale: (1) Azure, a pelican with wings endorsed vulning herself, or; (2) argent, thereon an escutcheon charged with the arms of the See of Winchester (i.e. gules, two keys addorsed in bend, the uppermost or, the other argent, a sword interposed between them in bend sinister of the third, pommel and hilt gold; the escutcheon ensigned with a mitre of the last); (3) sable, a chevron or between three owls argent, on a chief of the second as many roses gules, seeded of the second, barbed vert.[54]

The pelican is a reference to the college's name: corpus Christi means "the body of Christ", and the pelican was said to have offered its own blood to its children, just as Christ offers his body to his followers in the Eucharist. Because of the complexity of the arms they are not suitable for use on items such as the college crested tie, where the pelican is used instead. The pelican also appears alone on the college flag and on top of the Pelican Sundial.

The college has several "totem animals" besides the pelican: the fox, which recalls the founder's surname, and bees, which are a reference to the founder's stated desire to create an institution that would be a "hive of [scholarly] activity". The college maintains a hive of bees, and the glass front wall of the MBI Al Jaber auditorium is decorated with images of bees.

Traditions

The grace laid out in the founding statutes is still said before every formal dinner in hall:

Nos miseri et egentes homines pro hoc cibo, quem in alimonium corporis nostri sanctificatum es largitus, ut eo recte utamur, Tibi, Deus omnipotens, Pater caelestis, reverenter gratias agimus; simul obsecrantes, ut cibum angelorum, panem verum caelestem, Dei Verbum aeternum, Iesum Christum Dominum nostrum, nobis impertiaris, ut Eo mens nostra pascatur, et per carnem et sanguinem Eius alamur, foveamur, corroboremur.[55]

which translates to

We wretched and needy mortals give reverent thanks to you, almighty God, heavenly Father, for this food, which you have given us to nourish our bodies, praying at the same time that you may bestow on us the food of angels, the true heavenly bread, the eternal Word of God, Jesus Christ Our Lord, that our souls may feed on him, and that through his flesh and blood we may be nourished, cherished and strengthened.[55]

There is also a shorter grace said after dinner, which is now only used on special occasions.

The college traditionally keeps at least one tortoise as a living mascot, cared for by an elected 'Tortoise Keeper'. The 'Tortoise Fair', at which the Corpus tortoise(s) are raced against tortoises belonging to other colleges and local residents, is an annual event held to raise funds for charity. The current tortoise is named 'Foxe', after the founder of the college.[56]

Notable former students and fellows

Former students of the college include the philosopher Isaiah Berlin, the writer Vikram Seth, the financial commentator Martin Wolf, former Leader of the Labour Party Ed Miliband, and former Foreign Secretary David Miliband.

Presidents of Corpus Christi

The outgoing President is the theoretical physicist Professor Steven Cowley FRS, FREng, an international authority on astrophysical plasmas and nuclear fusion. Dr Helen Moore, Fellow and Tutor in English, serves as Acting President until 30 September 2019.[1]

Gallery

Entrance to the college

Entrance to the college Under the entrance Archway

Under the entrance Archway Hall

Hall

Notes

- ↑ The dial is currently held by Oxford Museum of the History of Science.[44]

References

- 1 2 http://www.ccc.ox.ac.uk/News/a/Dr-Helen-Moore-elected-Acting-President/

- 1 2 "Student statistics". University of Oxford. 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Corpus Christi College, Oxford (6 December 2017). "Annual Report & Financial Statements" (PDF). charitycommission.gov.uk. p. 17. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ Undergraduate Degree Classifications 2009/10 Archived 3 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ http://www.sundials.co.uk/tbpil.htm

- ↑ Pattenden, Philip (1979). Sundials at an Oxford College. Roman Books. ISBN 978-0950664408.

- ↑ Corpus Wins University Challenge – Oxford News

- ↑ "University Challenge team disqualified". BBC. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, pp. 6-7.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, p. 41.

- ↑ "Oldham, Hugh". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20685. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Salter, H. E.; Sobel, Mary D., eds. (1954). "Corpus Christi College". A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3, the University of Oxford. Victoria County History. London.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards & Reid 2017, pp. 70, 264.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, p. 15.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, p. 32.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, p. 18.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, Appendix A.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards & Reid 2017, pp. 64, 75–81.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards & Reid 2017, pp. 131–132.

- ↑ Gibbs, Lee W. (15 February 2008). "Life of Hooker". In Kirby, Torrance. A Companion to Richard Hooker. Brill's Companions to the Christian Tradition. 8. Brill. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-90-04-16534-2. ISSN 1871-6377.

- ↑ The Church History of Britain: From the Birth of Jesus Christ until the year MDCXLVIII, 3 (3rd ed.), Thomas Tegg (published 1842), 1655, p. 231

- ↑ Charles-Edwards & Reid 2017, p. 403.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Hudson, Paul Stephen (21 November 2016). "Oglethorpe University". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Charles-Edwards & Reid 2017, p. 31.

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1978, pp. 29, 131.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, p. 45.

- ↑ Fowler 1898, pp. 46, 222.

- ↑ Alan Baxter Associates (2014). "The Corpus Estate". Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

- ↑ Tyack 1998, p. 315.

- 1 2 "Completed Accomodation [sic] Projects". Corpus Christi College, Oxford. 2016.

- ↑ "The Lampl Building" (PDF). Sundial. No. 2. Corpus Christi College, Oxford. 2 September 2013. p. 10.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, p. 26.

- ↑ Pattenden 1983, p. 322.

- ↑ Pattenden 1983, p. 322–323.

- ↑ Pattenden 1983, p. 322–325.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, p. 30.

- 1 2 Pattenden 1979, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ "Polyhedral Dial, by Nicolaus Kratzer?, English, 1518–30". MHS Collection Database Search. Museum of the History of Science. Inventory Number 54054.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 48–53.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 55–57.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Pattenden 1979, pp. 64–70.

- ↑ "The Corpus Estate" (PDF). The Pelican Record. Corpus Christi College, Oxford. LII. December 2016.

- ↑ Pattenden 1983, p. 321.

- ↑ "Pomfret School Sundial, (sculpture)". Art Inventories Catalog. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Inventory of American Sculpture, Control Number CT000250.

- ↑ Oxford University Calendar 2001–2002 (2001) p.231. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-951872-6.

- 1 2 "General Information and College Rules" (PDF). Corpus Christi College, Oxford. September 2009. p. 31.

- ↑ Miller, Emily (2013-05-25). "Oxford in suspense for Corpus tortoise fair". Cherwell. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

Sources

- Charles-Edwards, Thomas; Reid, Julian (July 2017). Corpus Christi College, Oxford: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-879247-5.

- Fowler, Thomas (1898). Corpus Christi. Oxford University College Histories. Bloomsbury, London: F. E. Robinson & Co.

- Pattenden, Philip (1979). Sundials at an Oxford College. Roman Books. ISBN 0-9506644-0-5.

- Pattenden, Philip (June 1983). "Pelican Sundials in America". Bulletin of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. XXV (3). ISSN 0027-8688.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09639-9.

- Tyack, Geoffrey (19 March 1998). Oxford: An Architectural Guide. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-817423-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Corpus Christi College, Oxford. |

.jpg)