Keble College, Oxford

| Keble College | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxford | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Blazon: Argent, a chevron engrailed gules, on a chief azure, three mullets pierced or | ||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

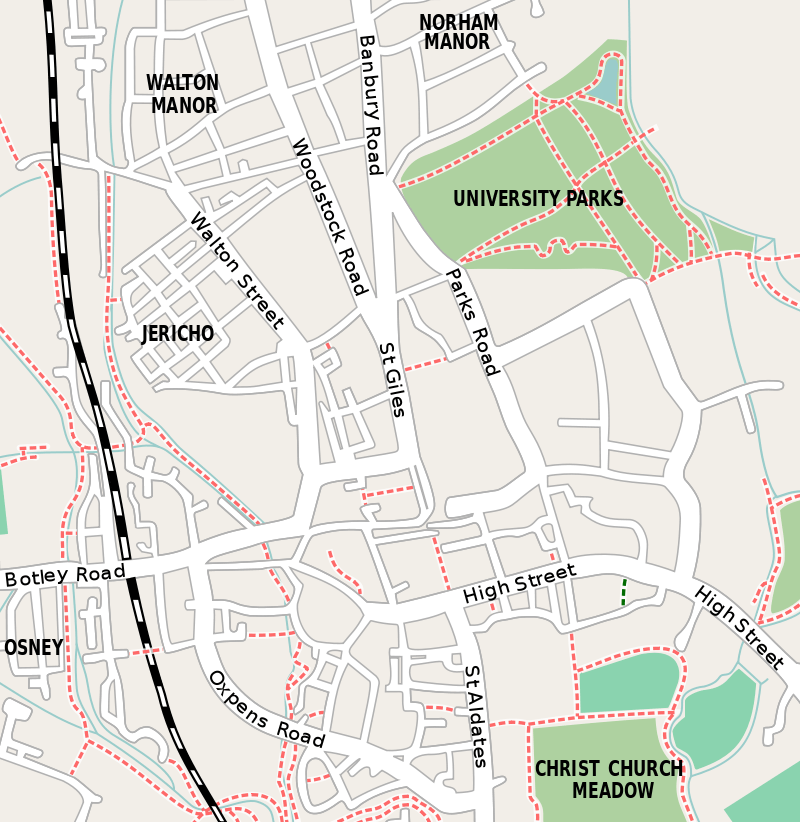

| Location | Parks Road | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′32″N 1°15′28″W / 51.758899°N 1.257715°WCoordinates: 51°45′32″N 1°15′28″W / 51.758899°N 1.257715°W | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Keblense | |||||||||||

| Motto | Plain living and high thinking[1] | |||||||||||

| Established | 1870 | |||||||||||

| Named for | John Keble | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Selwyn College, Cambridge | |||||||||||

| Warden | Sir Jonathan Phillips | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 425[2] | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 217[2] | |||||||||||

| Website |

www | |||||||||||

| Boat club |

www | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

Location in Oxford city centre | ||||||||||||

Keble College /ˈkiːbəl/ is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its main buildings are on Parks Road, opposite the University Museum and the University Parks. The college is bordered to the north by Keble Road, to the south by Museum Road, and to the west by Blackhall Road. It is the largest college by rooms at Oxford.

Keble was established in 1870, having been built as a monument to John Keble, who had been a leading member of the Oxford Movement which sought to stress the Catholic nature of the Church of England. Consequently, the college's original teaching focus was primarily theological, although the college now offers a broad range of subjects, reflecting the diversity of degrees offered across the wider university. In the period after the Second World War the trends were towards scientific courses (the major area devoted to science east of the University Museum influenced this). As originally constituted, it was for men only and the fellows were mostly bachelors resident in the college. Like many of Oxford's men's colleges, Keble admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979.[3]

It remains distinctive for its still-controversial[4] neo-gothic red-brick buildings designed by William Butterfield. The buildings are also notable for breaking from Oxbridge tradition by arranging rooms along corridors rather than around staircases, in order that the scouts could supervise the comings and goings of visitors. (Girton College, Cambridge, similarly breaks this tradition.)

Keble is one of the larger colleges of the University of Oxford, with 433 undergraduates and 245 graduate students in 2011/12.[5] Keble's sister college at the University of Cambridge is Selwyn College.

History

.jpg)

The best-known of Keble's Victorian founders was Edward Pusey, after whom parts of the college are named. The college itself is named after John Keble, one of Pusey's colleagues in the Oxford Movement, who died four years before the college's foundation in 1870. It was decided immediately after Keble's funeral that his memorial would be a new Oxford college bearing his name. Two years later, in 1868, the foundation stone was laid by the Archbishop of Canterbury on St Mark's Day (25 April, John Keble's birthday).[6] The college first opened in 1870, taking in thirty students, whilst the Chapel was opened on St Mark's Day 1876. Accordingly, the college continues to celebrate St Mark's Day each year.

William Butterfield, the original architect, a high churchman himself, produced a notable example of Victorian Gothic architecture, among his few secular buildings, which Pevsner characterised as "actively ugly",[7] and which, Charles Eastlake asserted, defied criticism.[8] The social historian G. M. Trevelyan expressed the then commonly held, and highly dismissive, view; "the monstrosities of architecture erected by order of the dons of Oxford and Cambridge colleges in the days of William Butterfield and Alfred Waterhouse give daily pain to posterity."[9] Sir Kenneth Clark recalled that during his Oxford years it was generally believed in Oxford not only that Keble College was "the ugliest building in the world" but that its architect was John Ruskin, author of The Stones of Venice.[10] The college is built of red, blue, and white bricks; the main structure is of red brick, with white and blue patterned banding. The builders were Parnell & Son of Rugby.

On its construction, Keble was not widely admired within the university, particularly by the undergraduate population of nearby St John's College (from which Keble had purchased their land). A secret society was founded,[11] entrance to which depended upon removing one brick from the college and presenting it to the society's elders. Some accounts specify that one of the commonest red bricks was necessary for ordinary membership, a rarer white brick for higher-level membership, and one of the rarest blue bricks for chairmanship. The hope was that eventually Keble would be completely demolished. As a result, there remains a healthy rivalry between St John's and Keble to this day.

An apocryphal story claims that a French visitor, on first sight of the college exclaimed C'est magnifique mais ce n'est pas la gare? ("It is magnificent but is it not the railway station?"). This is a play on Field Marshal Pierre Bosquet's memorable line, referring to the Charge of the Light Brigade, C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas la guerre ("It is magnificent, but it is not war"). This story may have been borrowed from Arthur Wing Pinero's identical quip said to have been made at the opening ceremony for the Royal Courts of Justice in London.

Keble is mentioned in John Betjeman's poem "Myfanwy at Oxford", as well as in the writings of John Ruskin and in Monty Python's "Travel Agent" sketch. Horace Rumpole, the barrister in John Mortimer's books, was a Law graduate of Keble.

In 2005, Keble College featured in the national UK press when its bursar, Roger Boden, was found guilty of racial discrimination by an employment tribunal.[12][13] An appeal was launched by the college and Boden against the tribunal's judgement, resulting in a financial out-of-court settlement with the aggrieved employee.

In Christmas of 2017, a team of alumni from Keble College won the University Challenge Alumni Christmas Special, a seasonal programme on BBC2. They beat the University of Reading by 240 points to 0 in the final.

Buildings

The best-known portion of Keble's buildings is the distinctive main brick complex, designed by Butterfield.[14] The design remained incomplete due to shortage of funds. The Chapel and Hall were built later than the accommodation blocks to the east and west of the two original quadrangles and the warden's house at the south-east corner. The Chapel and Hall were both fully funded by William Gibbs and were also designed by Butterfield.

Modern buildings

A section west of the Chapel was built in a different style in the 1950s with funds from Antonin Besse. Later still other significant additions have been added, most notably the modern, brick Hayward and de Breyne extensions by Ahrends, Burton and Koralek (ABK). The de Breyne extension was made possible by a generous response from the businessman André de Breyne and other fund-raising efforts. The ABK buildings included the college's memorable, futuristic "goldfish bowl" bar, opened on 3 May 1977 and recently refurbished and expanded. In 1995, work was completed on the ARCO building by the US-born architect Rick Mather. This was followed in 2002 by another similarly styled building also designed by Mather, the Sloane-Robinson building. Along with a number of additional student bedrooms the Sloane Robinson building also provided the college with the O'Reilly Theatre (a large multipurpose lecture theatre), a dedicated room for musical practice, a number of seminar rooms and a large open plan space which during term time is used as a café and social space for all members of the college.

The college contains four quads: Liddon (the largest), Pusey, Hayward and Newman. The original fellows garden was lost in the programme of extension, as were a range of houses on Blackhall Road.

In July 2004 Keble announced the purchase of the former Acland Hospital for £10.75 million. This 1.7-acre (6,900 m2) site, situated a couple of minutes walk from the main college buildings, housed an estimated 100 graduate students. In October 2015 it was confirmed that Keble College had received funding from The HB Allen Charitable Trust to redevelop the Acland Site in order to provide double the number of graduate rooms. This was the largest single donation in the college's history.[15] Work on construction of the HB Allen Centre, designed by Rick Mather, began in 2016, with the first graduate students moving in in October 2018. The graduate centre will be fully operational in early 2019. Keble previously owned a number of houses across Oxford which were used as additional student accommodation, but these were sold following the purchase of the Acland site.

Student life

The college publishes a termly magazine called The Brick which is sent to Keble alumni to update them on College life. Students used to publish an irreverent spoof version on the last Friday of each term, also named The Brick, recording college gossip but this version has not been published since Hilary 2006. The college has since seen the release of a student publication calling itself The Breezeblock, containing both college gossip and a satirical take on college life.

Each graduate is given a red brick along with their degree certificates.

Keble were champions of the television quiz show University Challenge in 1975 and 1987.

Each year the Advanced Studies Centre invites distinguished speakers for their Creativity Lecture Series. In 2011 the list included Nicholas Humphrey, Tim Ingold and Steve Rayner; in 2012 Robin Dunbar, Kevin Warwick and Margaret Boden were featured.

The Keble Ball is planned by the student committee to coincide with the day-long graduation ceremony in Trinity term week 2,[16] although in 2020 the 150 year commemoration ball will be held in week 9 outside of term.

Sport

Keble fields a number of sports teams. Its rugby teams have been successful in winning the intercollegiate league for five seasons in a row and triumphing in the 2007, 2009, 2011 and 2015 rugby Cuppers, having also been finalists in 2008 and 2010. Keble College Boat Club, the college rowing club compete annually in Torpids and Summer Eights.

Keble College Sports Ground is located on Woodstock Road, and as well as hosting intercollegiate ("Cuppers") matches, also lays the stage for annual fixtures between current undergraduates and Old Members ("Ghosts"), particularly in football and cricket. Commemorative photographs of important matches adorn the walls of the Keble Cricket Pavilion inside the ground.

The Light of the World

Keble owns the original of William Holman Hunt's famous painting The Light of the World, which is hung in the side chapel (accessed through the chapel). The picture was completed in 1853 after eight years of work, and originally hung in the Royal Academy. It was then given as a gift to the college. Hunt originally wanted the painting to be hung in the main chapel but the architect rejected this idea, as a result he painted another version of the painting which is in St Paul's Cathedral, London. This copy was painted by Hunt when he was nearly 70.

College stamps

Keble College has the distinction of being the first college to issue stamps for the prepayment of a porter/messenger delivery service in 1871 only one year after it was founded, and it set the pace for other Oxford Colleges to issue their own stamps. This service was successfully challenged by the post office in 1886.

Keble also issued a College stamp in 1970 to mark its 100th anniversary.

Notable members of Keble

Andrew Adonis, British Labour Party politician

Andrew Adonis, British Labour Party politician David Wilson, former Governor of Hong Kong

David Wilson, former Governor of Hong Kong Imran Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, former Pakistan cricket captain, former chancellor of Bradford University and chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

Imran Khan, Prime Minister of Pakistan, former Pakistan cricket captain, former chancellor of Bradford University and chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

References

- ↑ Judy G. Batson. Her Oxford. Vanderbilt University Press. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-8265-1610-7. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

plain living and high thinking

- 1 2 "Keble College - University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk.

- ↑ Keble past and present. Archer, Ian W., Cameron, Averil. London: Third Millennium. 2008. ISBN 9781903942710. OCLC 232983257.

- ↑ In 1875, a writer in The Guardian dismissed Butterfield's Chapel as "fantastically picked out with zig-zag or checkerboard ornamentation", to which Butterfield responded stoutly in print, citing his East Anglian and Cotswold precedents: Paul Thompson, William Butterfield, 1971, noted in a review by J. Mordaunt Crook in The English Historical Review 1974.

- ↑ "Undergraduate numbers by college 2011–12". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 2 December 2012.

- ↑ Samuel Wilberforce (1868). "The Resurrections of the Truth: A Sermon, preached in the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin, Oxford, on Saint Mark's Day, April 25, 1868, being the Day of Laying the First Stone of Keble College".

- ↑ Sherwood & Pevsner 1996, p. 227.

- ↑ Eastlake, A History of the Gothic Revival "Chapel of Baliol College, Oxford", p 261f.

- ↑ Trevelyan 1944, p. 524.

- ↑ Clark 1962, p. 2.

- ↑ "Jack Nory – Columns". The Oxford Student. Archived from the original (Official Student Newspaper) on 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Taylor, Matthew (8 April 2005). "Oxford college guilty of race discrimination". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Employment Tribunal (Reading) case no. 2701126/04". Archived from the original on 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Bill Risebero. Modern Architecture and Design: An Alternative History. MIT Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-262-68046-2. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ↑ "Keble College receives largest donation in its history for major new development – University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Keble Ball".

Sources

- Clark, Kenneth (1962). The Gothic Revival: An Essay in the History of Taste. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-3102-0.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1996). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09639-2.

- Trevelyan, G. M. (1944). English Social History: A Survey of Six Centuries. London: Longmans. OCLC 465934298.

Further reading

- Parkes, M. B., comp. (1979) The Medieval Manuscripts of Keble College Oxford: a descriptive catalogue, with summary descriptions of the Greek and oriental manuscripts. xxi, 365 pp.; facsimiles. London: Scolar Press ISBN 0-85967-504-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keble College, Oxford. |