André Gide

| André Gide | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

André Paul Guillaume Gide 22 November 1869 Paris, French Empire |

| Died |

19 February 1951 (aged 81) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Cimetière de Cuverville, Cuverville, Seine-Maritime |

| Occupation | Novelist, essayist, dramatist |

| Education | Lycée Henri-IV |

| Notable works |

L'immoraliste (The Immoralist) La porte étroite (Strait Is the Gate) Les caves du Vatican (The Vatican Cellars; sometimes published in English under the title Lafcadio's Adventures) La Symphonie Pastorale (The Pastoral Symphony) Les faux-monnayeurs (The Counterfeiters) |

| Notable awards |

Nobel Prize in Literature 1947 |

| Spouse | Madeleine Rondeaux Gide |

| Children | Catherine Gide |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

| Website | |

|

andregide | |

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

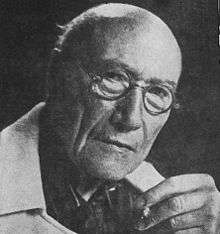

André Paul Guillaume Gide (French: [ɑ̃dʁe pɔl ɡijom ʒid]; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the symbolist movement, to the advent of anticolonialism between the two World Wars. The author of "more than fifty books," at the time of his death his obituary in The New York Times described him as "France's greatest contemporary man of letters" and "judged the greatest French writer of this century by the literary cognoscenti."[1]

Known for his fiction as well as his autobiographical works, Gide exposes to public view the conflict and eventual reconciliation of the two sides of his personality, split apart by a straitlaced traducing of education and a narrow social moralism. Gide's work can be seen as an investigation of freedom and empowerment in the face of moralistic and puritanical constraints, and centres on his continuous effort to achieve intellectual honesty. His self-exploratory texts reflect his search of how to be fully oneself, including owning one's sexual nature, without at the same time betraying one's values. His political activity is informed by the same ethos, as indicated by his repudiation of communism after his 1936 voyage to the USSR.

Early life

Gide was born in Paris on 22 November 1869, into a middle-class Protestant family. His father was a Paris University professor of law who died in 1880. His uncle was the political economist Charles Gide. His paternal family traced its roots back to Italy, with his ancestors, the Guido's, moving to France and other western and northern European countries after converting to Protestantism during the 16th century, due to persecution.[2][3][4]

Gide was brought up in isolated conditions in Normandy and became a prolific writer at an early age, publishing his first novel, The Notebooks of André Walter (French: Les Cahiers d'André Walter), in 1891, at the age of twenty-one.

In 1893 and 1894, Gide travelled in Northern Africa, and it was there that he came to accept his attraction to boys.[5]

He befriended Oscar Wilde in Paris, and in 1895 Gide and Wilde met in Algiers. Wilde had the impression that he had introduced Gide to homosexuality, but, in fact, Gide had already discovered this on his own.[6][7]

The middle years

In 1895, after his mother's death, he married his cousin Madeleine Rondeaux,[8] but the marriage remained unconsummated. In 1896, he became mayor of La Roque-Baignard, a commune in Normandy.

In 1901, Gide rented the property Maderia in St. Brélade's Bay and lived there while residing in Jersey. This period, 1901–07, is commonly seen as a time of apathy and turmoil for him.

In 1908, Gide helped found the literary magazine Nouvelle Revue Française (The New French Review).[9] In 1916, Marc Allégret, only 15 years old, became his lover. Marc was the son – one of five children – of Elie Allégret, who years before had been hired by Gide's mother to tutor her son in light of his weak grades in school, after which he and Gide became fast friends; Allégret was best man at Gide's wedding. Gide and Marc fled to London, in retribution for which his wife burned all his correspondence – "the best part of myself," he later commented. In 1918, he met Dorothy Bussy, who was his friend for over thirty years and translated many of his works into English.

In the 1920s, Gide became an inspiration for writers such as Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. In 1923, he published a book on Fyodor Dostoyevsky; however, when he defended homosexuality in the public edition of Corydon (1924) he received widespread condemnation. He later considered this his most important work.

In 1923, he sired a daughter, Catherine, by Elisabeth van Rysselberghe, a woman who was much younger than he. He had known her for a long time, as she was the daughter of his closest female friend, Maria Monnom, the wife of his friend the Belgian neo-impressionist painter Théo van Rysselberghe. This caused the only crisis in the long-standing relationship between Allégret and Gide and damaged the relation with van Rysselberghe. This was possibly Gide's only sexual liaison with a woman,[10] and it was brief in the extreme. Catherine became his only descendant by blood. He liked to call Elisabeth "La Dame Blanche" ("The White Lady"). Elisabeth eventually left her husband to move to Paris and manage the practical aspects of Gide's life (they had adjoining apartments built for each on the rue Vavin). She worshiped him, but evidently they no longer had a sexual relationship. Gide's legal wife, Madeleine, died in 1938. Later he explored their unconsummated marriage in his memoir of Madeleine, Et Nunc Manet in Te.

In 1924, he published an autobiography, If it Die... (French: Si le grain ne meurt).

In the same year, he produced the first French language editions of Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and Lord Jim.

After 1925, he began to campaign for more humane conditions for convicted criminals.

Africa

From July 1926 to May 1927, he travelled through the French Equatorial Africa colony with his lover Marc Allégret. Gide went successively to Middle Congo (now the Republic of the Congo), Ubangi-Shari (now the Central African Republic), briefly to Chad and then to Cameroon before returning to France. He related his peregrinations in a journal called Travels in the Congo (French: Voyage au Congo) and Return from Chad (French: Retour du Tchad). In this published journal, he criticized the behavior of French business interests in the Congo and inspired reform.[11] In particular, he strongly criticized the Large Concessions regime (French: régime des Grandes Concessions), i.e., a regime according to which part of the colony was conceded to French companies and where these companies could exploit all of the area's natural resources, in particular rubber. He related, for instance, how natives were forced to leave their village for several weeks to collect rubber in the forest, and went as far as comparing their exploitation to slavery. The book had important influence on anti-colonialism movements in France and helped re-evaluate the impact of colonialism.[12]

Russia

During the 1930s, he briefly became a communist, or more precisely, a fellow traveler (he never formally joined any communist party). As a distinguished writer sympathizing with the cause of communism, he was invited to speak at Maxim Gorky's funeral and to tour the Soviet Union as a guest of the Soviet Union of Writers. He encountered censorship of his speeches and was particularly disillusioned with the state of culture under Soviet communism, breaking with his socialist friends in Retour de L'U.R.S.S. in 1936.

Then would it not be better to, instead of playing on words, simply to acknowledge that the revolutionary spirit (or even simply the critical spirit) is no longer the correct thing, that it is not wanted any more? What is wanted now is compliance, conformism. What is desired and demanded is approval of all that is done in the U. S. S. R.; and an attempt is being made to obtain an approval that is not mere resignation, but a sincere, an enthusiastic approval. What is most astounding is that this attempt is successful. On the other hand the smallest protest, the least criticism, is liable to the severest penalties, and in fact is immediately stifled. And I doubt whether in any other country in the world, even Hitler's Germany, thought to be less free, more bowed down, more fearful (terrorized), more vassalized.

— André Gide Return from the U. S. S. R.[13]

In the 1949 anthology The God That Failed Gide describes his early enthusiasm:

My faith in communism is like my faith in religion: it is a promise of salvation for mankind. If I have to lay my life down that it may succeed, I would do so without hesitation.

— André Gide, The God That Failed

It is impermissible under any circumstances for morals to sink as low as communism has done. No one can begin to imagine the tragedy of humanity, of morality, of religion and of freedoms in the land of communism, where man has been debased beyond belief.

1930s and 1940s

In 1930 Gide published a book about the Blanche Monnier case called La Séquestrée de Poitiers, changing little but the names of the protagonists. Monnier was a young woman who was kept captive by her own mother for more than 25 years.[15][16]

In 1939, Gide became the first living author to be published in the prestigious Bibliothèque de la Pléiade.

He left France for Africa in 1942 and lived in Tunis until the end of World War II. In 1947, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature "for his comprehensive and artistically significant writings, in which human problems and conditions have been presented with a fearless love of truth and keen psychological insight".[17] He devoted much of his last years to publishing his Journal.[18] Gide died in Paris on 19 February 1951. The Roman Catholic Church placed his works on the Index of Forbidden Books in 1952.[19]

Gide's life as a writer

Gide's biographer Alan Sheridan summed up Gide's life as a writer and an intellectual:

Gide was, by general consent, one of the dozen most important writers of the 20th century. Moreover, no writer of such stature had led such an interesting life, a life accessibly interesting to us as readers of his autobiographical writings, his journal, his voluminous correspondence and the testimony of others. It was the life of a man engaging not only in the business of artistic creation, but reflecting on that process in his journal, reading that work to his friends and discussing it with them; a man who knew and corresponded with all the major literary figures of his own country and with many in Germany and England; who found daily nourishment in the Latin, French, English and German classics, and, for much of his life, in the Bible; [who enjoyed playing Chopin and other classic works on the piano;] and who engaged in commenting on the moral, political and sexual questions of the day.[20]

"Gide's fame rested ultimately, of course, on his literary works. But, unlike many writers, he was no recluse: he had a need of friendship and a genius for sustaining it."[21] But his "capacity for love was not confined to his friends: it spilled over into a concern for others less fortunate than himself."[22]

Writings

André Gide's writings spanned many genres – "As a master of prose narrative, occasional dramatist and translator, literary critic, letter writer, essayist, and diarist, André Gide provided twentieth-century French literature with one of its most intriguing examples of the man of letters."[23]

But as Gide's biographer Alan Sheridan points out, "It is the fiction that lies at the summit of Gide's work."[24] "Here, as in the oeuvre as a whole, what strikes one first is the variety. Here, too, we see Gide's curiosity, his youthfulness, at work: a refusal to mine only one seam, to repeat successful formulas...The fiction spans the early years of Symbolism, to the "comic, more inventive, even fantastic" pieces, to the later "serious, heavily autobiographical, first-person narratives"...In France Gide was considered a great stylist in the classical sense, "with his clear, succinct, spare, deliberately, subtly phrased sentences."

Gide's surviving letters run into the thousands. But it is the Journal that Sheridan calls "the pre-eminently Gidean mode of expression."[25] "His first novel emerged from Gide's own journal, and many of the first-person narratives read more or less like journals. In Les faux-monnayeurs, Edouard's journal provides an alternative voice to the narrator's." "In 1946, when Pierre Herbert asked Gide which of his books he would choose if only one were to survive," Gide replied, 'I think it would be my Journal.'" Beginning at the age of eighteen or nineteen, Gide kept a journal all of his life and when these were first made available to the public, they ran to thirteen hundred pages.[26]

Struggle for values

"Each volume that Gide wrote was intended to challenge itself, what had preceded it, and what could conceivably follow it. This characteristic, according to Daniel Moutote in his Cahiers de André Gide essay, is what makes Gide's work 'essentially modern': the 'perpetual renewal of the values by which one lives.'"[27] Gide wrote in his Journal in 1930: "The only drama that really interests me and that I should always be willing to depict anew, is the debate of the individual with whatever keeps him from being authentic, with whatever is opposed to his integrity, to his integration. Most often the obstacle is within him. And all the rest is merely accidental."[28]

As a whole, "The works of André Gide reveal his passionate revolt against the restraints and conventions inherited from 19th-century France. He sought to uncover the authentic self beneath its contradictory masks."[29]

Sexuality

In his journal, Gide distinguishes between adult-attracted "sodomites" and boy-loving "pederasts", categorizing himself as the latter.

I call a pederast the man who, as the word indicates, falls in love with young boys. I call a sodomite ("The word is sodomite, sir," said Verlaine to the judge who asked him if it were true that he was a sodomist) the man whose desire is addressed to mature men. […]

The pederasts, of whom I am one (why cannot I say this quite simply, without your immediately claiming to see a brag in my confession?), are much rarer, and the sodomites much more numerous, than I first thought. […] That such loves can spring up, that such relationships can be formed, it is not enough for me to say that this is natural; I maintain that it is good; each of the two finds exaltation, protection, a challenge in them; and I wonder whether it is for the youth or the elder man that they are more profitable.[30]

In the company of Oscar Wilde, he had several sexual encounters with young boys abroad.

Wilde took a key out of his pocket and showed me into a tiny apartment of two rooms… The youths followed him, each of them wrapped in a burnous that hid his face. Then the guide left us and Wilde sent me into the further room with little Mohammed and shut himself up in the other with the [other boy]. Every time since then that I have sought after pleasure, it is the memory of that night I have pursued. […] My joy was unbounded, and I cannot imagine it greater, even if love had been added.

How should there have been any question of love? How should I have allowed desire to dispose of my heart? No scruple clouded my pleasure and no remorse followed it. But what name then am I to give the rapture I felt as I clasped in my naked arms that perfect little body, so wild, so ardent, so sombrely lascivious? For a long time after Mohammed had left me, I remained in a state of passionate jubilation, and though I had already achieved pleasure five times with him, I renewed my ecstasy again and again, and when I got back to my room in the hotel, I prolonged its echoes until morning.[31]

Gide's novel Corydon, which he considered his most important work, erects a defense of pederasty.

Bibliography

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "new york time obituary". www.andregide.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ Wallace Fowlie, André Gide: His Life and Art, Macmillan (1965), p. 11

- ↑ Pierre de Boisdeffre, Vie d'André Gide, 1869-1951: André Gide avant la fondation de la Nouvelle revue française (1869-1909), Hachette (1970), p. 29

- ↑ Jean Delay, La jeunesse d'André Gide, Gallimard (1956), p. 55

- ↑ If It Die: Autobiographical Memoir by André Gide (first edition 1920) (Vintage Books, 1935, translated by Dorothy Bussy: "but when Ali – that was my little guide's name – led me up among the sandhills, in spite of the fatigue of walking in the sand, I followed him; we soon reached a kind of funnel or crater, the rim of which was just high enough to command the surrounding country...As soon as we got there, Ali flung the coat and rug down on the sloping sand; he flung himself down too, and stretched on his back...I was not such a simpleton as to misunderstand his invitation"..."I seized the hand he held out to me and tumbled him on to the ground." [p. 251]

- ↑ Out of the past, Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the present (Miller 1995:87)

- ↑ If It Die: Autobiographical Memoir by André Gide (first edition 1920) (Vintage Books, 1935, translated by Dorothy Bussy: "I should say that if Wilde had begun to discover the secrets of his life to me, he knew nothing as yet of mine; I had taken care to give him no hint of them, either by deed or word....No doubt, since my adventure at Sousse, there was not much left for the Adversary to do to complete his victory over me; but Wilde did not know this, nor that I was vanquished beforehand or, if you will...that I had already triumphed in my imagination and my thoughts over all my scruples." [p. 286])

- ↑ "André Gide (1869-1951) - Musée virtuel du Protestantisme". www.museeprotestant.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ André Gide Biography. nobelprize.org

- ↑ White, Edmund (10 December 1998). "On the chance that a shepherd boy …". pp. 3–6. Retrieved 20 March 2018 – via London Review of Books.

- ↑ "André Gide - Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ Voyage au Congo suivi du Retour du Tchad Archived 16 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine., in Lire, July–August 1995 (in French)

- ↑ Return from the U. S. S. R. translated D. Bussy (Alfred Knopf, 1937), pp. 41-42

- ↑ André Gide as [http://www.heggy.org/books/imperative/chapter_8.htm quoted by Tarek Heggy Archived 7 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine. in his book Culture, Civilization, and Humanity (2003). ISBN 0-7146-5554-6

- ↑ Pujolas, Marie. En tournage, un documentaire sur l'incroyable affaire de "La séquestrée de Poitiers". France TV info. Feb 27, 2015

- ↑ Levy, Audrey. Destins de femmes: Ces Poitevines plus ou moins célèbres auront marqué l'Histoire. Le Point. Apr 21, 2015.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1947". www.nobelprize.org. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ↑ "André Gide (1869–1951)". Musée virtuel du Protestantisme français. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ André Gide Biography (1869–1951). eninimports.com

- ↑ André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan. Harvard University Press, 1999, pages p. xvi.

- ↑ Alan Sheridan, p. xii.

- ↑ Alan Sheridan, p. 624.

- ↑ Article on André Gide in Contemporary Authors Online' 2003. Retrieved with library card October 2014.

- ↑ Information in this paragraph is extracted from André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan, pp. 629-33.

- ↑ Information in this paragraph is extracted from André Gide: A Life in the Present by Alan Sheridan, pages 628.

- ↑ Journals: 1889-1913 by André Gide, trans. by Justin O'Brien, p. xii.

- ↑ Quote taken from the article on André Gide in Contemporary Authors Online, 2003. Retrieved with library card October 2014.

- ↑ Journals: 1889-1913 by André Gide, trans. by Justin O'Brien, p. xvii.

- ↑ Quote taken from the article on André Gide in the Encyclopedia of World Biography, Dec. 12, 1998, Gale Pub. Retrieved with library card October 2014.

- ↑ Gide, Andre (1948). The Journals Of André Gide, Vol II 1914-1927. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 246–247. ISBN 978-0252069307. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ↑ Gide, Andre (1935). If It Die: An Autobiography (New ed.). Random House. p. 288. ISBN 978-0375726064. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

Sources

- Alan Sheridan, André Gide: A Life in the Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Further reading

- Noel I. Garde [Edgar H. Leoni], Jonathan to Gide: The Homosexual in History. New York:Vangard, 1964. OCLC 3149115

- For a chronology of Gide's life, see pages 13–15 in Thomas Cordle, André Gide (The Griffin Authors Series). Twayne Publishers, Inc., 1969.

- For a detailed bibliography of Gide's writings and works about Gide, see pages 655-678 in Alan Sheridan, André Gide: A Life in the Present. Harvard, 1999.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: André Gide |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to André Gide. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: André Gide |

- Website of the Catherine Gide Foundation, held by Catherine Gide, his daughter.

- Center for Gidian Studies

- Works by André Gide at Project Gutenberg

- Works by André Gide at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about André Gide at Internet Archive

- Works by André Gide at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Amis d'André Gide in French

- Period newspaper articles on Gide interface in French

- André Gide, 1947 Nobel Laureate for Literature

- André Gide: A Brief Introduction

- Gide at Maderia in Jersey, 1901–7

- Bibliowiki has original media or text related to this article: André Gide (in the public domain in Canada)

- Newspaper clippings about André Gide in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)